In The erroneous ‘lets have a little, some or no MMT’ narrative

(http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=41627)

… for Paul Krugman! Where would one start?

On March 26, 2011, he wrote this Op Ed – A Further Note On Deficits and the Printing Press – which focused on MMT (one of his early attacks).

I considered that Op Ed in this blog post two days later – Letter to Paul Krugman (March 28, 2011).

It traced in some detail, Krugman’s evolving statements about fiscal deficits and public debt, including his disastrous misunderstanding of the Japanese situation in the 1990s, where he was throwing spurious advice around, right, left and centre.

Two days before the March 26, 2011 Op Ed, his article – The Austerity Delusion – probed the following issue, for example:

But couldn’t America still end up like Greece? Yes, of course. If investors decide that we’re a banana republic whose politicians can’t or won’t come to grips with long-term problems, they will indeed stop buying our debt.

That tells you a lot.

There is a litany of similar erroneous comments throughout several media articles by the same author.

In the March 26, 2011 Op Ed he warned everyone that:

… running large deficits without access to bond markets is a recipe for very high inflation, perhaps even hyperinflation. And no amount of talk about actual financial flows, about who buys what from whom, can make that point disappear: if you’re going to finance deficits by creating monetary base, someone has to be persuaded to hold the additional base.

With the massive expansion of central bank balance sheets since that time and the fact (see below) that central bankers are losing their fight to bring inflation rates up – in Europe, in Japan, etc – the lack of wisdom from Krugman is obvious.

He then wrote (again attacking MMT) that:

As I understand the MMT position, it is that the only thing we need to consider is whether the deficit creates excess demand to such an extent to be inflationary. The perceived future solvency of the government is not an issue.

Quite apart from the misrepresentation of the MMT position, he was claiming that governments could become insolvent if they issued to must debt and that was something that MMT failed to acknowledge.

Okay, MMT does establish that a currency issuing government cannot become insolvent – in the sense, that it can always fund any outstanding liabilities in its own currency – unless it chooses for political reasons to default.

It could never justify such a political choice using financial logic.

But that is not the point here.

Fast track to December 14, 2017, and an interview that Paul Krugman gave to Ezra Klein for Vox – “An orgy of serious policy discussion” with Paul Krugman.

Ezra Klein asked him about the likelihood of an impending public debt crisis, given the increase in public debt over the preceding years.

Krugman replied as follows:

It’s very hard to try and tell a coherent story about how this alleged debt crisis can even happen. I’ve been through this. I’ve given presentations at the IMF, where I say, “Look, I believe for a country that looks like the United States, a debt crisis is fundamentally not possible,” and people will say, “Well, I can’t quite fault your logic here, but I don’t believe it.” It really is more about a gut feeling than it is about any kind of theory.

“fundamentally not possible”.

Then fast track to his latest attack on MMT (February 12, 2019) – What’s Wrong With Functional Finance? (Wonkish) – where he is back to making stuff up.

Things like “MMTers …. tend to be unclear about what exactly their differences with conventional views are”.

He hasn’t read much.

He also castigates the frenzied lot in 2010s who, in the face of the rising American deficits, used the “‘Eek! We’re turning into Greece!’ panic” to attack the federal government.

And refer back to Krugman’s own use of the Greek scare (…)!

But the real point he tries to make now is that MMTs association with Abba Lerner’s functional finance is problematic because Lerner didn’t see that:

… debt potentially more of a problem than he acknowledges.

And then he gets into the ridiculous New Keynesian claim (…) that debt sustainability depends on whether:

… the interest rate is higher or lower than the economy’s sustainable growth rate … if r>g you do have the possibility of a debt snowball: the higher the ratio of debt to GDP the faster, other things equal, that ratio will grow …

So when attacking MMT debt matters.

Otherwise a debt crisis is “fundamentally not possible”.

Consistency is a good thing.

Shill.

Gehigarriak:

Krugman: 15 urte igaro ondoren

Paul Krugman eta Warren Mosler

Paul Krugman eta Warren Mosler (Who is Who?)

Randall Wray-ek Paul Krugman-i buruz

Paul Krugman DTMrekin bat, Eskozia tartean

Zorra: Paul Krugman? Ez, mila esker!

Paul Krugman eta Warren Mosler, zorrari buruz

Paul Krugman eta Hyman Minsky: Randall Wray, Stephanie Kelton eta Warren Molser

‘Erregea’ (Paul Krugman) biluzik dago, erabat

Defizitak, Paul Krugman eta Pavlina Tcherneva

Paul Krugman eta euroa (azkena)

Stephanie Kelton @StephanieKelton ots. 13

(https://twitter.com/wbmosler/status/1095640877899358210)

Stephanie Kelton(e)k Bertxiotua Scott Fullwiler

MMT ≠ Functional Finance

Stephanie Kelton(e)k gehitu du,

Scott Fullwiler @stf18

Now Krugman’s playing the #MMTdrinkinggame too … Can’t trust pols to cut deficits … Drink!…

Honi erantzuten: @StephanieKelton

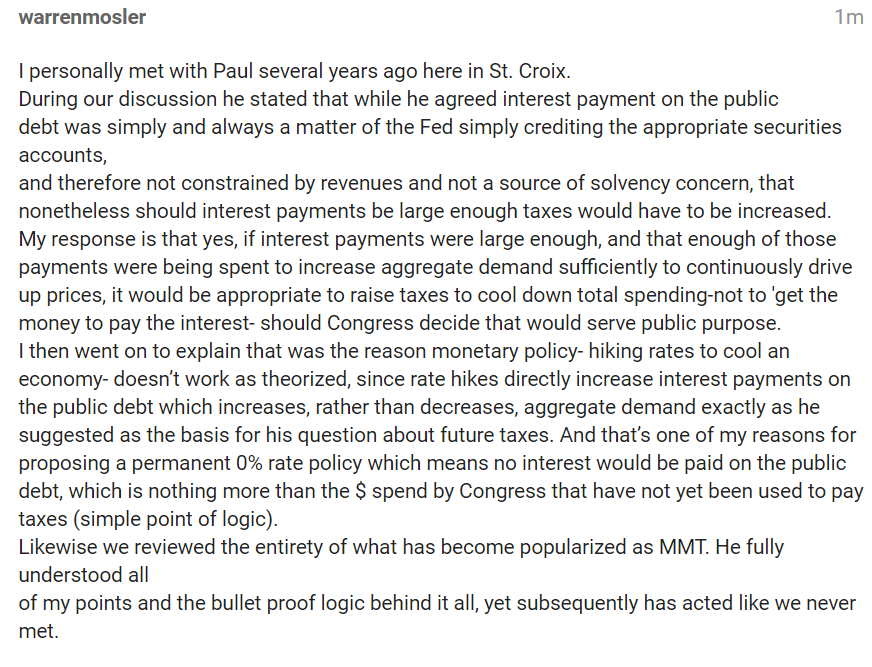

Personal discussion with Paul several years ago:

2019 ots. 13

joseba says:

Modern Monetary Theory Is Not a Recipe for Doom

There are no inherent tradeoffs between fiscal and monetary policy.

(https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2019-02-21/modern-monetary-theory-is-not-a-recipe-for-doom)

Stephanie Kelton is a professor of public policy and economics at Stony Brook University. She was the Democrats’ chief economist on the staff of the U.S. Senate Budget Committee and an economic adviser to the 2016 presidential campaign of Senator Bernie Sanders.

Paul Krugman first wrote about modern monetary theory on March 25, 2011. He last wrote about MMT in a two-part series on February 12-13, 2019. Although he’s had almost a decade to come to terms with the approach, he is still getting some of the basic ideas wrong.

This matters for two reasons: one, because people listen to Paul Krugman, who won the Nobel economics prize in 2008, and, two, because the approach he is discussing is at the heart of how to design economic policies that affect millions of Americans. I’d like to try to move the conversation forward by addressing his concerns.

He begins by saying, “MMT seems to be pretty much the same thing as Abba Lerner’s ‘functional finance’ doctrine from 1943.” Krugman then sets out to critique Lerner’s functional finance, which he says “applies to MMT as well.”

It’s actually not correct to say that modern monetary theory is pretty much the same thing as Lerner’s functional finance. MMT draws insights and inspiration from Lerner’s work — including his “Money as a Creature of the State” — but the American academics who are most associated with MMT would argue that the contributions of Hyman Minsky and Wynne Godley are at least as important to the project, and probably more so. So, a critique of functional finance is not a critique of MMT but a critique of one component part of the broader macro approach.

But let’s go ahead and examine what Krugman thinks MMT — er, Abba Lerner — gets wrong. For those who aren’t familiar with Lerner’s approach, here’s the thumbnail version: The government should use its fiscal powers (spending, taxing and borrowing) in whatever manner best enables it to maintain full employment and price stability. Basically, he’s saying Congress, not the Federal Reserve, should have the dual mandate.

Lerner abhorred the doctrine of “sound finance,” which held that deficits should be avoided, instead urging policymakers to focus on delivering a balanced economy rather than a balanced budget. That might require persistent deficits, but it might also require a balanced budget or even budget surpluses.

It all depends how close the private sector comes to delivering full employment on its own. In any case, the government should focus on inflation and not worry about deficits or debt, per se.

Krugman says there are two problems with Lerner’s thinking and, by extension, MMT. “First, Lerner neglected the tradeoff between monetary and fiscal policy.”

Specifically, Krugman complains that Lerner was too “cavalier” in his discussion of monetary policy since he called for the interest rate to be set at the level that produces “the most desirable level of investment” without saying exactly what that rate should be.

It’s an odd critique, since Krugman himself subscribes to the idea that monetary policy should target an invisible “neutral rate,” a so-called r-star that exists when the economy is neither depressed nor overheating. For what it’s worth, research suggests the neutral rate “may be flat-out wrong,” and Fed Chairman Jerome Powell has admitted that the Fed has been too cavalier in relying “on variables that cannot be measured directly and which can only be estimated with great uncertainty.”

But Lerner wasn’t trying to use interest rates to optimize the economy. That was a job for fiscal policy. He argued that the government should be prepared to spend whatever is necessary to sustain full employment without raising taxes or borrowing.

Unless it risked creating an inflation problem, Lerner wanted the government to cut taxes or spend newly issued money and just leave it in the economy. But he also understood that this could cause interest rates to “be reduced too low…and induce too much investment, thus bringing about inflation.”

For that reason, Lerner suggested that the government might want to sell bonds in order to mop up excess money (reserves) to the point that the short-term interest rate rose enough to prevent excessive investment. Otherwise, the low interest rates brought about by rising deficits might “crowd in” more investment spending and overheat the economy. In other words, Lerner had a completely different way of thinking about the relationship between deficits, interest rates and the purpose of ‘borrowing.’

He was worried about the potential crowding-in effects of fiscal policy, not the crowding-out effects Krugman believes are part of an inherent tension—tradeoff—between fiscal and monetary policy. Lerner understood that deficits could drive interest rates down and spur too much investment, thus his support of bond sales to maintain higher interest rates. In this way, borrowing was not about financing deficits but hitting some desired interest rate. MMT agrees and makes the same point.

Krugman’s other objection is that Lerner “didn’t fully address the limitations, both technical and political, on tax hikes/or spending cuts” as a means of fighting inflation.

In fact, Lerner actually had quite a lot to say about this. Here’s the opening sentence to an entire chapter on the subject in his 1951 book “The Economics of Employment”: “We have now concluded our treatment of the economics of employment, but a word or two must be added on the politics and the administration of employment policies in general and of Functional Finance in particular” (emphasis in original).

Here’s Krugman’s concern: What if lawmakers made policy the way Lerner thought they should, and it put us in a situation where somewhere down the road, we ended up with a debt-to-GDP ratio of 300 percent, and an interest rate that is higher than the growth rate?

Krugman says, “to stabilize the ratio of debt to GDP would require a primary surplus equal to 4.5 percent of GDP.” And then he wonders how we’re going to get there. “Are we going to slash Medicare and Social Security?”

I have three responses.

First, “there is a devil in the interest rate assumption,” as economist James K. Galbraith has explained. Preventing a doomsday scenario is not difficult. As Galbraith explains, “the prudent policy conclusion is: keep the projected interest rate down.” Or, putting it more crudely, “It’s the Interest Rate, Stupid!”

Since interest rates are a policy variable, all the Fed has to do is keep the interest rate below the growth rate (ig, then debt service grows faster than GDP, which Krugman argues would be inflationary.

So his hypothetical scenario begs the question: Why would an inflation-targeting Fed permit i>g with a debt-to-GDP ratio at 300 percent?

Japan serves as a pretty good example here, with a debt ratio that might well rise to 300 percent one day. Meanwhile, rates sit right where the Bank of Japan sets them, and the government easily sustains its primary deficits.

Second, if we’re so obsessed with debt sustainability, why are we still borrowing? Remember, Lerner didn’t think of borrowing as a financing operation. He saw it as a way to conduct monetary policy – that is, to drain reserves and keep interest rates at some desired rate — as I explained here.

But the Fed no longer relies on bonds (open-market operations) to hit its interest rate target. It just pays interest on reserve balances at the target rate. Why not phase out Treasuries altogether? We could pay off the debt “tomorrow.”

If that seems too extreme, why not restrict duration to three-month T-bills so interest rates always sit within a hair of the overnight rate? And if we wanted to embark on a World War II-like mobilization for a Green New Deal, Congress could instruct the Fed to cap interest rates the way it did during the actual mobilization for WWII. In other words, there are many ways to deal with the technical and administrative problems that concern Krugman.

Finally, Krugman, like most of the economics profession, appears to assume that the short-term interest rate is the only tool available to the Fed to slow the economy. MMT disagrees, and many central banks around the world do, too.

As just one possible alternative, the Fed could raise margins of safety on lending, such as lower maximum loan-to-value or debt service-to-cash flow ratios. Less credit would be extended, consistent with the Fed’s goal of slowing the economy, while the interest rate on the national debt would not rise. A potential benefit to raising margins of safety, compared with raising short-term rates, is that credit extended could come with reduced risks of default.

Where does that leave us? Paul Krugman and I agree on a great many things, but we come at certain questions from a fundamentally different place.

He believes there are inherent tradeoffs between fiscal and monetary policy. Outside of the so-called liquidity trap, Krugman adopts the standard line that budget deficits crowd out private investment because deficits compete with private borrowing for a limited supply of savings.

The MMT framework rejects this, since government deficits are shown to be a source (not a use!) of private savings. Some careful studies show that crowding-out can occur, but that it tends to happen in countries where the government is not a currency issuer with its own central bank.

This seems like a disagreement we should be able to resolve either empirically or intuitively. But who knows? As Lerner wrote, “a man convinced against his will retains the same opinion still.”

joseba says:

NMF-ko Lagarde andrea eta DTM

Bill Mitchell-en Madame Lagarde basically says MMT is correct – not that she knew she was saying it!

(http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=42122)

(i) NMF, Lagarde andrea, Japonia, DTM

(…) we have some fun at the IMF to discuss (briefly). On April 11, 2019, IMF boss Madame Lagarde gave a press conference to open the 2019 Spring Meetings. The Transcript – includes the Madame waxing lyrical about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). And you might have confused the press conference for a stand-up comedy routine except you would have to be ‘in the know’ to laugh. But the significant aspect of the conference came when a question from Japan focused on MMT. In attempting to put down our work, Madame Lagarde actually admitted that a situation where the government runs big fiscal deficits, has a large-scale and on-going public debt-issuance program, where the central bank buys substantial proportions of that issuance, apparently ‘works’ under conditions that the currency-issuing government can always control. MMT 101. QED. Have a laugh.

(ii) NMF-ko nagusia ete Japonia

IMF Boss makes a fool of herself – again

There is growing interest in MMT and Japan after the Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, Finance Minister Taro Aso and Bank of Japan Haruhiko Kuroda all claimed that “Japan is experimenting with” MMT.

The press reported that this august trio had (Source):

… also rejected the MMT view that countries with their own central banks and borrowing in their own currencies — like the U.S. and Japan — can’t go broke, and don’t need to worry about overspending so long as it’s not generating high inflation.

Another Japanese politician (in Opposition), one Takeshi Fujimaki, a former banker, claimed that the Japanese government would regret implementing the sort of “reflationary policies” that MMT proponents would advocate in the situation that Japan has found itself in after the massive property crash in the early 1990s.

He told the press:

MMT is “ridiculous” and “voodoo economics … [it] … absolutely no different … [from what Japan is doing]

So at least he gets that the Japanese government is using its currency-issuing capacity to the advantage of its citizens and rejecting the ‘sound finance’ types which would have it cut deficits by imposing austerity.

Of course, he gets it wrong by advocating austerity.

The interest about MMT and Japan is increasing though and I am doing an extended interview with the New York Times tomorrow about all this stuff given that I have followed Japan and its fiscal matters closely for many years.

Anyway, during the Press Conference, Madame Lagarde had the following interchange with a representative from the Japanese press:

QUESTION – Thank you very much. My question is about the Modern Money Theory (MMT).

Madame Lagarde – It applies in Japan as well?

QUESTION – We do not have much inflation ‑‑ United States, Europe, basically zero growth, low inflation. If we have low inflation, we can have much more debt. No problemo. No problem. How convincing is that theory to you? Is that OK to have more debt in the name of filling the gap between the poor and the rich? Thank you very much.

Madame Lagarde – We do not think that the Modern Monetary Theory is actually a panacea. There are very, very, very limited circumstances where it could work. We do not think that any country is, you know, currently in a position where that theory could actually deliver good value in a sustainable way.

So while it is tempting, when you look at the sort of mathematical modeling of it, and it seems to stand, there are big caveats about it, such as, if the country is in a liquidity trap, such as if there is deflation. Well, then in those circumstances, it could possibly work for a short period of time, probably, because interest rates stay low until such time when they start going up. And then it is a bit of a trap. So that would be our view.

All right.

All wrong!

But wait a moment!

Did she just say that the things that MMT proponents derive from their understanding of the way the monetary system operates actually work and their mathematical modelling proves it?

Sure did!

(iii) Lagarde andrea

Madame Lagarde has probably not read anything about MMT other than some scattered stuff in the mainstream press and perhaps one of her lackey economists has told her a few things.

First, she doesn’t understand that MMT is not a regime but a window into the world of the monetary systems that operate all around the world.

In that sense, it can never be constructed as “a panacea”.

To think of it as a policy regime (“a panacea”) means that you don’t get the most fundamental aspects of our work.

Second, her claim that their are “very, very, very limited circumstances where it could work” response reinforces her ignorance.

It ‘works’ everywhere there is a currency-issuer and currency. How it ‘works’ depends on how the capacities of the currency-issuer are made operational. But it ‘works’ everywhere.

Third, what she is talking about are certain policy applications that are in place.

And as Takeshi Fujimaki recognises, Japan has adopted a policy stance where the government sector has chosen to provide substantial support to the non-government sector to allow it to save overall while still allowing the economy to grow.

The Government has focused on avoiding recessions and keeping unemployment low rather than be seduced by the wall of criticism that its deficits are too large, or its debt will send it broke, or that bond markets will stop buying the debt.

The Japanese Government knows that:

1. The Bank of Japan can keep short-term interest rates around zero for as long as it wants – which means the longer-maturity investment rates are always low.

2. The Bank of Japan can always buy any amount of the public debt that is issued and never face insolvency.

3. That deficits can be as large as is required to sustain high levels of employment and simultaneously fund the desire of the non-government sector to save.

4. That inflation will not follow from this sort of monetary stance while there are idle resources that can be brought into productive use through appropriately scaled fiscal deficits.

That knowledge is in direct contradiction to the myths that the mainstream macroeconomists disseminate but core MMT.

So the denial of the Japanese political elite (including the central bank boss) that they are doing this and that MMT is crazy stupid is very funny.

Fourth, according to Madame Lagarde, the IMF has done macroeconomic modelling of our work according to her and it “seems to stand” up!

I would be interested in them releasing that work for public scrutiny.

And it- by which I presume we mean Japanese-style fiscal deficits, on-going public debt-issuance and central bank buying substantial proportions of that issuance (almost all the public debt issued since December 2012 has been purchased by the Bank of Japan) – apparently ‘works’ as long as interest rates stay low.

Which means that it ‘works’ whenever the government wants it to ‘work’ because as Japan has demonstrated since the early 1990s, the Bank of Japan can keep interest rates low for as long it as wants.

In other words, whether this sort of policy ‘works’ has nothing to do with the ‘market’ and is not a special case. It is purely a function of the policy choice that the Government makes and the cooperation within the Government between Treasury/Finance and the central bank).

I am sure Madame Lagarde didn’t understand that her attempted put down was actually an endorsement of the insights that MMT provides.