Ezaguna da EBZ-k ezin duela, legez, EBko estatukideei diru laguntzak eman, ezta haien zor publikoa erosi ere.

Badakigu, halaber, Ezkerra, oro har, eta EBn bereziki, erabat galduta dagoela-

Hala ere, ikus dezagun EBZ-ren jokaera azken urte hauetan.

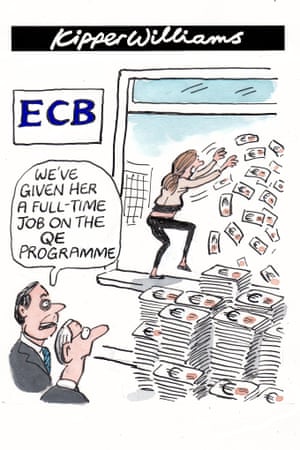

Badakigu zertarako den QR delakoa: QE, historian egondako aberastasunaren transferrik handiena

(In Mario Draghi eta QE berria)

Hala ere, hona zenbait datu:

(i) Hasiera: Mario Draghi, EBZ eta nola hasi zen ‘guztia’

(in Mario Draghi eta…)

Draghi’s words (euroa salbatzearren):

Whatever It Takes (Jul-12)

Whatever We Must (Nov-15)

Without Undue Delay; No Limits (Dec-15)

We Don’t Give Up (Jan-16)

August 9, 2007

On this day 10 years ago, the ECB launched a fine-tuning operation injecting €94.8bn in the banking system. And so it all started.

(ii) ‘Erreskateak’ nonahi, baita Espainian ere: Mario Draghi eta Espainia

El Banco Central Europeo (BCE) ya tiene en su poder más del 18% de la deuda pública española. Los más de 200.000 millones de euros que Draghi ha prestado al Gobierno ponen en duda la realidad de la recuperación de Mariano Rajoy.

En verano de 2012, hace un lustro, el presidente del BCE, Mario Draghi, pronunciaba su ya célebre frase “haré lo necesario para salvar el euro”. Desde ese momento, la entidad que preside arrancó un plan de compra de activos públicos y privados mediante el cual se compran 60.000 millones de euros mensuales en bonos.

Solo unas semanas más tarde, Draghi anunciaba que compraría deuda soberana española en el mercado secundario, o sea: deuda ya emitida en circulación que suele estar en manos de otros inversores. Este anuncio lo hizo poco después de declarar que los gobiernos que recibieran este tipo de ayudas indirectas deberían someterse a “condiciones estrictas” y que estaba en manos del Gobierno español aceptar esa compra. Rajoy aceptó y la prima de riesgo española bajó al mismo tiempo que el BCE inyectaba dinero mediante la compra de deuda de varios países europeos.

Pero tres años más tarde, la cosa no parecía mejorar y Draghi volvió a sorprender, en enero de 2015, con el aviso de que la compra de bonos públicos se intensificaría y que se compraría deuda de gobiernos y otras entidades públicas europeas. El plan, conocido como Quantitative Easying (QE), comenzó en marzo de ese mismo año. Desde entonces, el BCE no ha dejado de comprar deuda pública que ha aliviado la presión de los tipos de interés a pagar a los mercados por parte de algunos países europeos, incluido España.

(…)

En dos meses el BCE ha comprado el doble de deuda española de lo que exige para cumplir el déficit

Desde el inicio de este plan hasta el mes de julio de este año, el BCE ha adquirido 201.103 millones de euros de deuda pública española. Un 18,17% de la deuda total del Estado y un 11,9% de los fondos utilizados para comprar activos públicos desde que comenzó el QE, que alcanzan ya la cifra de 1,690 billones de euros.

(…)

España no es la única, aunque está entre las más endeudadas con la institución europea. Según los datos anunciados por el BCE, España es el cuarto país en el ranking de deuda soberana en su poder. La entidad presidida por Draghi atesora más de 400.000 millones de euros de bonos de deuda alemana. Francia se encuentra en la segunda posición, con 325.000 millones. Italia es la tercera con 283.000 millones de euros de deuda en sus cartera del BCE.

(…)

Draghi también rescata al Ibex35

Los gobiernos no son los únicos en salir beneficiados de esta financiación barata y segura. El BCE también lleva comprando deuda y bonos a empresas privadas no financieras desde junio de 2016. En el mes de junio adquirió 5.606 millones de euros en bonos emitidos por estas empresa. Desde el inicio de esta discutida y polémica medida, Draghi ha comprado 102.206 millones de euros de deuda a empresas privadas.”

(iii) Tarteko eredu bat: Japonia ezberdina ote? Ez, politika fiskalak funtzionatzen du

(iv) Ezkerra?: Ezkerraz, zer egin eta nola?

(c) Reclaiming the State[1]

(d) Nazioarteko ordena berria estatu subirano independenteetan eta interdependenteetan oinarritua[2]

(v) Banku zentralak (eta EBZ): Banku zentralak, gobernu defizitak eta zerua bere lekuan

Ondorioak:

(a) This sort of analysis shows that central banks have been funding government deficits in the US (and similar patterns exist elsewhere as the Financial Times article shows).

(b) Nothing untoward has happened.

(c) The sky is still firmly above our heads.

(d) As a proponent of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), I do not consider there to be a public debt problem so the analysis presented here is to document what has been happening.

(e) What it shows is that even within the voluntarily-constrained system that regulates the relationship between the US treasury and the central bank, the latter can still effectively buy as much US government debt as it likes.

(f) So if yields rise on US Treasury debt in the coming year it will be because the US government has chosen to allow higher interest payments on the corporate welfare it extends the non-government sector in the form of voluntary debt-issuance.

(g) The question that financial commentators really should be asking is why should the US government extend that corporate welfare to domestic bond-buyers and foreign governments/private investors.

(h) There is no financial reason (in terms of facilitating fiscal policy) for the bond issuance. It is just a form of welfare spending which helps the top-end-of-town.

(i) I would actually like the central bank to just debit and credit treasury bank accounts as required and for governments to dispense with the charade of issuing debt altogether.

(vi) Politika fiskala: Politika fiskala eraginkorra da eta erabiltzeko segurua

(x) Banku zentralen ‘pragmatismoa’[3]

(c) EBZ-ren jokaeraz[4]

(vii) Nazio-estatuaren beharra: Estatua eskatuz, nonahi

(ix) Estatuen botereaz[5]

Beraz,

(A) Inongo arazorik gabe EBZ-k, nahi duenean, “euroa salbatzearren”, edozein neurri har dezake, kasu, QE bezalakoa

(B) Horrek suposatzen du EBZ´k, teklatuen bidez dirutza barreiatzen duela, nahi duen beste eta gura dituen erakundeetara: bankuak, enpresak, gobernuak,…

(C) EBZ-k ez dauka inolako arazorik gobernuen zor publikoa ‘erosteko’

Hortaz,

(D) Zergatik ez erabili politika fiskala zuzenean, defizita areagotuz, teklatuen bidez behar den euro kopurua EBko kide diren estatu kideei defizitak %3tik %8ra igoz?

(E) Zein de arazoa?

[1] Ingelesez: “Globalization and the State

Furthermore, throughout the 1970s and 1980s, a new (fallacious) Left consensus started to set in that economic and financial internationalization—what today we call “globalization”—had rendered the state increasingly powerless vis-à-vis “the forces of the market.” Therefore, the reasoning went, countries had little choice but to abandon national economic strategies and all the traditional instruments of intervention in the economy—such as tariffs and other trade barriers, capital controls, currency and exchange rate manipulation, and fiscal and central bank policies. Instead they could only hope, at best, for transnational or supranational forms of economic governance. In other words, government intervention in the economy came to be seen not only as ineffective but, increasingly, as outright impossible. This process—which was generally (and erroneously) framed as a shift from the state to the market—was accompanied by a ferocious attack on the very idea of national sovereignty, increasingly vilified as a relic of the past. As we argue in Reclaiming the State, the Left—in particular the European Left—played a crucial role in this regard as well, by cementing this ideological shift towards a postnational and post-sovereign view of the world, often anticipating the Right on these issues.”

[2] Ingelesez: “One of the most consequential turning points in this respect was François Mitterrand’s 1983 turn to austerity—the so-called tournant de la rigueur—just two years after the French Socialists’ historic victory in 1981. Mitterrand’s election had inspired the widespread belief that a radical break with capitalism—at least with the extreme form of capitalism that had recently taken hold in the Anglo-Saxon world—was still possible. By 1983, however, the French Socialists had succeeded in “proving” the exact opposite: that neoliberal globalization was an inescapable and inevitable reality. As Mitterrand stated at the time: “National sovereignty no longer means very much, or has much scope in the modern world economy. . . . A high degree of supra-nationality is essential.””

[3] Ingelesez: “But intrinscally, there is no necessity to do that. And these voluntary constraints have a habit of being relaxed quicksmart when circumstances dictate. Note the substantial rise in the proportion of government debt held by central banks since the recession!

That is, central banks have been effectively funding a substantially increased portion of government deficits in many nations without anyone blinking much. Even in the Eurozone where such ‘bailouts’ are apparently banned.

Pragmatism ruled. Thankfully.”

[4] Ingelesez: “Second, the ‘fiscal actions’ of the ECB (for example, the Securities Markets Program introduced in May 2010) clearly showed that the currency issuing authority can effectively fund any size deficits at low to negative yields any time it wants even if the designated fiscal authority (the Eurozone Member States) are effectively states in a federation, without their own currency issuing capacity.

So the experience of the Eurozone taught us nothing about the “limits of fiscal policy”. Rather, it reinforced the power of the fiscal policy and the capacity of the currency-issuing authority.”

[5] Ingelesez: “ (…)

2. “quantitative easing has demonstrated the importance of monetary sovereignty” – it has, in fact, demonstrated that central banks can control yields on public debt at whatever level they choose.

And the logical inference is that Central banks can fund any size fiscal deficits if they choose.

And, governments, in fact, do not even need to issue debt in order to run deficits. That is what the GFC demonstrated to anyone who wanted to keep their eyes open.

It is what Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) proponents have been arguing since day dot! (…)”