The Bridge – Scott Ritter Extra

The Bridge

6 Oct 2023

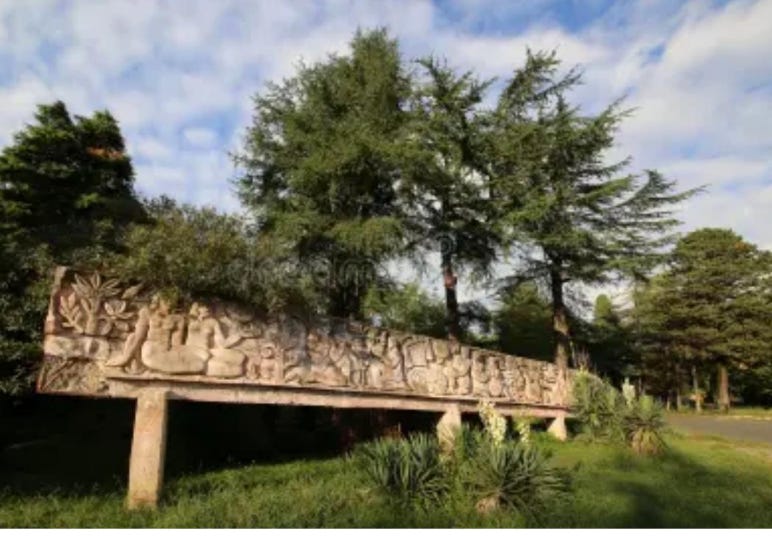

The Kelasuri Rail and Road Bridge, Sukhumi, Georgia

A new Georgian film, Liza, Go On, has been released in theaters in time to mark the 30th anniversary of the end of the 1992-93 Abkhazian war. Directed by Nana Janelidze, the movie is based upon the real-life experiences of Lia Toklikishvili, who covered the conflict for major Georgian newspapers. “If we don’t confess and repent,” the lead character in the move declares, “we won’t get anything back.”

The movie draws upon the recollections and diaries of participants and witnesses of the Abkhazian war. Many of those who watched the film believed that the movie unjustly portrayed Georgia as the guilty party to the conflict, and as a result insulted the memory of those who fought and died in the war. Others praised the film for provoking the audience into thinking about the conflict in a new way.

I have not seen the movie. What I do know is that October 3 marked the 30th anniversary of when my father-in-law, Bidzina Khatiashvili—one month shy of his 63rd birthday—emerged from the Greater Caucasus mountains and walked into the village of Chuberi. He had spent days walking alongside a literal stream of humanity—tens of thousands of desperate men, women, and children—who were fleeing for their lives ahead of the victorious forces of Abkhazian separatists who, on September 27, 1993, captured the city of Sukhumi, effectively ending a war that had been raging since August 1992.

During his time in the mountains, Bidzina had seen tragedy most humans cannot imagine, and should never experience. Somehow, Bidzina survived where so many did not. As he made his way from Chuberi to the city of Zugdidi, Bidzina put his six decades of life to that point behind him. He would come to live with our family – my wife Marina, our twin daughters and me – in America. Bidzina would spend the better part of the next three decades building a new home in a new country. But Sukhumi was never far from his thoughts, and to his dying breath he dreamed of once again walking on the soil of a land he called home.

Scott Ritter will discuss this article and answer audience questions on Ep. 104 of Ask the Inspector.

Bidzina was an academic, a teacher at the Sukhumi Institute of Subtropical Agronomy, nestled in the hills above the city of Sukhumi, on the shores of the Black Sea. As accomplished as he was as a teacher (he was a department chair), Bidzina’s real passion was growing things. In Georgia, he had purchased a plot of land near the village of Merkheuli, located in the foothills of the Caucasus mountains along the Machara River. There, he planted a field of corn alongside apple and peach trees and row after row of fresh vegetables, including his favorite—tomatoes. After a long day in the classroom, Bidzina would flee to his beloved plot of land, tending lovingly to the bountiful harvest he helped coax from its fertile soil. I had the pleasure of visiting Bidzina in his Merkheuli retreat and watching a master at work.

The causes of the Abkhazian conflict of 1992-93 are many, and complex. For an academician like Bidzina, they were irrelevant. For him, the war began when Georgian forces entered Sukhumi in August 1992, setting off a confrontation with Abkhazian separatists that soon morphed into a general war. The Sukhumi Institute of Subtropical Agronomy, where Bidzina worked, was closed. Bidzina and the other academics—men in their 40’s, 50’s and 60’s—were conscripted into the Sukhumi Garrison as combatants, and organized into a company-sized security force assigned the task of guarding the Kelasuri Bridge, which marked the southern approach to the city of Sukhumi.

A ceasefire had been signed in July 1993, bringing the fighting to an end. By September 1, life had returned to normal in Sukhumi. Women and children who had fled the city during the worst of the fighting had returned, and schools were reopened. One September 16, however, the Abkhazians broke the ceasefire, and launched what would be the final assault on Sukhumi. The Georgian defenders, stripped of their heavy weapons by the terms of the ceasefire, were helpless in the face of the overwhelming firepower possessed by the Abkhazian forces, who had their heavy weapons returned to them by the Russians military. For eleven days the Georgians resisted, urged on by the President of Georgia himself, Eduard Shevardnadze, who flew into the stricken city to rally international attention to the plight of the Georgians there, to no avail. On September 25, the Abkhazian forces broke through the Georgian defenses north of the city. Two days later the entire city was under their control.

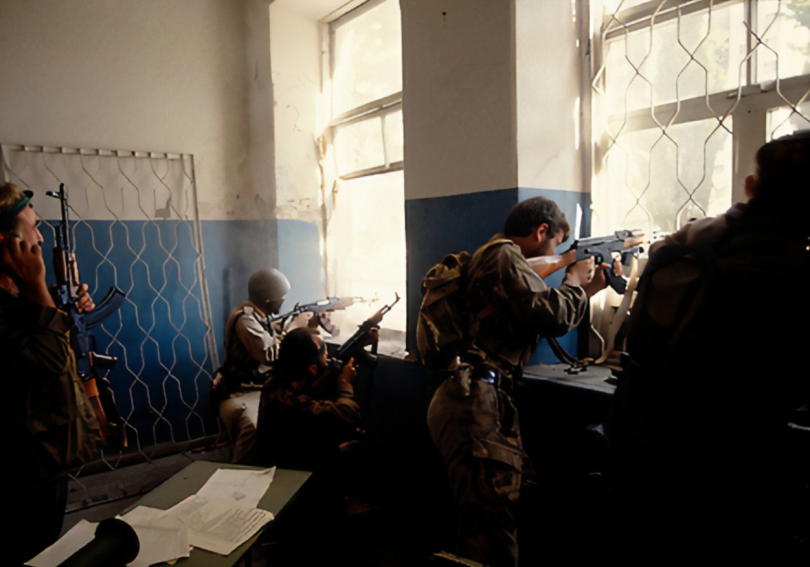

Georgian soldiers retreat from Sukhumi, September 1993

I’ve often thought back on the events of September 27, 1993—the day the Georgian defenders of Sukhumi broke and ran, abandoning those Georgian civilians who remained in the city to their fate. Bidzina was on duty that morning, an amateur soldier standing watch as the professionals ran away.

The first to cross were the Georgian Army, fleeing in trucks and whatever armored vehicles they had left. They were well armed, capable of continued resistance. And yet they fled.

The next were the fighters of the White Eagle militia. They, too, were well armed, well equipped, and, like their brothers in arms in the army, intent on leaving the city.

The last to go were the Mkhedrioni. Riding in whatever vehicles they could commandeer, these fighters were angry, bitter…embarrassed. Bidzina used to stop them when they entered the city, and was taken aback by their brazenness, their arrogance, their cruelty. Now, fleeing the city, these once haughty Georgians would not meet Bidzina’s stare, averting their eyes to hide the shame they felt at having failed to live up to their hype.

I wonder what was going through Bidzina’s mind at that moment. When I put himself in his shoes, and try to envision the fall of Sukhumi, I can only do so from the basis of my personal experiences. Bidzina had taken me to Mount Trapetsia, rising from the center of Sukhumi like a green sentinel, where the Institute of Experimental Pathology and Therapy maintained over 6,000 monkeys that were used in medical and scientific experimentation. I had wandered the grounds, amazed by the spectacle of so many monkeys in one location.

The Institute of Experimental Pathology and Therapy, Sukhumi

In addition to assisting in the development of vaccines (a plaque of a statue of a Baboon set in the courtyard leading into the institute lists the various diseases the institute helped fight), the institute supported the Soviet space program, with monkeys from the Sukhumi nursery used for experiments that included some of them being sent into orbit. The last pair of monkeys from the Sukhumi, named Krosha and Ivasha, were sent into space on December 29, 1992, before returning, in good health, on January 10, 1993. The simian cosmonauts were retired to a zoo in Adler, where they lived long and healthy lives.

The same cannot be said about their fellow apes and monkeys who remained in Sukhumi.

In the 1970’s a small sanctuary was opened in the Gumista river valley, where 60 hamadryas baboons were set free in an experiment to see if they would survive in the northern latitudes. The primates thrived, and by the time the war started in August 1992, the population had grown to over 600 primates. While the climate suited the baboons, they were dependent upon food being provided by the institute. When war came, the food deliveries stopped. The baboons, driven into the mountains by the sounds of war, soon starved to death—none survived the first winter.

War came to the Institute of Experimental Pathology and Therapy in the form of the Bagramyan Battalions, formed from the local Armenian community in Abkhazia. The Armenians had strived to remain neutral when the conflict initially broke out, but the depravations of the Georgian forces—especially Jaba Ioseliani’s Mkhedrioni—resulted in their joining the Abkhazian cause. A total of 1,500 Armenians participated in the war, comprising nearly a quarter of the total Abkhazian army. The first battalion of Armenians was formed in February 1993; a second battalion, composed of veteran Armenian soldiers from Nagorno-Karabakh, was organized in the spring of 1993. The Armenians were in the thick of the fighting, and 242 lost their lives as a result.

On July 25, the Armenians, operating from positions in and around the village of Yashtuha, nestled in the heights that dominated Sukhumi to the east, began to advance along the Besletka River. By September 26 they had reached the grounds of the institute. Dozens of monkeys were killed in the crossfire between the Armenians and the Georgian defenders, and scores more escaped from cages damaged in the fighting, creating a surreal scene where monkeys ran wild in the streets of Sukhumi while battles raged all around them (less that 250 of the institute’s 7,000 primates survived the war.)

Sukhumi Botanical Gardens

On the morning of September 27, the Armenians pushed into the city center from Mount Trapestia. As one battalion pivoted south, capturing the Red Bridge, thereby sealing off the last available line of retreat for the Georgian forces operating to the north, the other broke into the grounds of the Sukhumi botanical gardens. Marina and I had spent hours strolling these grounds, admiring the wide variety of flora that flourished there. Bidzina, his passion being all living things that could be coaxed from the soil of the earth, also loved the gardens. Later, after coming to live with us outside New York City, Bidzina would often visit the Bronx botanical garden, which he would wistfully compare its Sukhumi counterpart.

The last time I walked along the paved paths that cut through the verdant majesty of the gardens was in mid-July 1991. I remember the moment when Marina and I emerged from the gardens onto the grounds of the Council of Ministers, its massive white structures and green lawns contrasted against the blue of a Black Sea summer sky. The Armenians of the Bagramyan Battalion moved down these same paths, using the trees and shrubs of the botanical garden as cover, until they, too, beheld the same sight.

Inside the Council of Ministers building were gathered the last defenders of Sukhumi, dozens of police officers and soldiers who, together with the remnants of the Georgian Government of the Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia, were making their last stand. The commander of the Georgian forces was Mamia Alasania, a colonel in the Georgian Army who had led the first Georgian forces into Sukhumi back in August 1992. He was joined by the last vestiges of Georgian authority in Abkazia—Zhiuli Shartava, the Chair of the Council of Ministers of the Abkhazian Autonomous Republic; Guram Gabiskiria, the mayor of Sukhumi; Alexander Berulava, the head of Military Press-Center; Raul Eshba, an ethnic Abkhaz politician, and Sumbat Saakian, an ethnic Armenian politician. The Georgians, in the eyes of the Abkhazians and their allies, were responsible for all of the hardships that had befallen their people since the fighting broke out in August 1992. And the Abkhaz and Armenian politicians were, simply put, considered traitors within their respective communities.

On the morning of September 27, Bidzina had listened to the last, desperate appeal of Eduard Shevardnadze, who was by now safely outside the reach of the Abkhaz and their allies, to the defenders of Sukhumi:

“I know that you understand the challenge we are facing. I know how difficult the situation is. Many people left the city but you remain here for Sukhumi and for Georgia…. I call on you, citizens of Sukhumi, fighters, officers, and generals: I understand the difficulties of being in your position now, but we have no right to step back, we all have to hold our ground. We have to fortify the city and save Sukhumi. I would like to tell you that all of us—Government of Abkhazia, Cabinet of Ministers, Mr. Zhiuli Shartava, his colleagues, the city and regional government of Sukhumi, are prepared for action. The enemy is aware of our readiness, that’s why he is fighting in the most brutal way to destroy our beloved Sukhumi. I call on you to keep peace, tenacity, and self-control. We have to meet the enemy in our streets as they deserve.”

Zhuili Sharteva was an engineer by vocation. Guram Gabiskira was an historian turned soccer coach, and Raul Eshba a journalist. Sukhumi is a small city, and the intelligentsia tend to gather in the same social circles. As an accomplished academic in his own right, Bidzina knew these three men very well, having socialized with them over the years. Sharteva and his colleagues were fulfilling their mission, holding their ground when no one else would. They were doing what Shevardnadze had promised to do—“I will not leave this town which has been treacherously deceived once again,” the Georgian leader had proclaimed in a radio announcement on September 18, only to flee the city aboard the last flight out of Sukhumi airport ten days later. They had been promised support, but none came. One had to believe that they were resigned to their fate as they hunkered down in the offices and hallways of the Council of Ministers building.

The Abkhazian State University

The Armenians arrived outside the Council of Ministers complex shortly before 10 AM. There, they found a reconnaissance unit from the Karbada Battalion, composed of volunteers from neighboring the Kabardino-Balkaria autonomous republic, heavily engaged with Georgian forces deployed in an around the Council of Ministers building. Commanded by Muaed Shorov, and numbering 27 men, the Karbarda recon unit had advanced on the Council of Ministers building, believing it to be abandoned. They were immediately taken under fire from Ukrainian volunteers fighting on the side of the Georgians, who were positioned in the upper floors of the structure. The Ukrainians were soon joined by around 150 Georgian soldiers and policemen, assisted by a BRDM-2 armored car parked outside the building, forcing the Karbadians to take cover in the nearby Abkhazian State University, located adjacent to the Council of Ministers complex.

In 1990, Marina began a job with the Abkhazian State University as an English/Literature teacher. The university was divided into three sections—Abkhaz, Georgian, and Russian. Marina taught students from the Georgian section. Classes were still underway when I arrived in Sukhumi in late June 1991, and I would visit Marina during her breaks from instructing. The goodwill and pleasant atmosphere I encountered during my visits belied the fact that this same university had been at the center of a controversy in 1989, when the Abkhazian students and faculty sought to break away from the university and organization as a separate Abkhaz institution. This act led to the riots that tore through Sukhumi, killing scores and injuring hundreds. Two years and two months after my visit, the university was once again on the front lines of the Abkhaz-Georgian conflict, this time playing a supporting role in the final act of Georgian governance over Sukhumi.

Abkhazian soldiers fire on the Council of Minister’s building from inside the Abkhazian State University

The Armenians surrounded the Council of Minister’s building, sealing the fate of those trapped inside. The Karbardians and Armenians were soon joined by the Abkhaz Battalion, led by Aki Arzdinba, who brought with them heavy weapons, including a tank and mobile artillery rocket launchers, which were directed at the Georgian defenders inside the Council of Ministers building. For nearly three hours the gunbattle raged. During this time, the Council of Minister’s building caught fire, and soon the heart of the building was fully engulfed in flames, forcing the defenders to move to lower floors, thereby sacrificing the height advantage they enjoyed up until that moment. Gradually the fire from the Georgian troops died down, the defenders either being killed by the Abkhaz and their allies, or running out of ammunition.

Around 12.30 PM a single Georgian soldier emerged, bearing a white flag. Muaed Shorov met with the emissary, who passed on a request from Zhuili Sharteva that the defenders be granted safe passage to their own lines. Shorov refused this request, and instead demanded that all survivors surrender to him unconditionally. The wounded would be provided with medical treatment, Shorov said, and all the prisoners would be treated humanely. Shorov stated that he would resume the attack if his terms were not accepted within 20 minutes. Shortly thereafter, the Georgian emissary returned. Sharteva was willing to accept Shorov’s terms, under one condition—the Georgians would surrender only to the Kabardians. Shorov agreed.

The Council of Minister’s building on fire shortly before the Georgian surrender

Shorov and his men followed the Georgian emissary into the Council of Minister’s building, to the second floor, where they found Sharteva, his fellow parliamentarians, and around 30 Georgian special forces and police under the command of Colonel Alasnia. The bodies of dozens of dead defenders, including several Ukrainians, were scattered throughout the building. Sharteva, Alasnia, and the surviving Georgians surrendered their weapons, and were briefly interrogated by Shorov, before being led out of the building under guard. Two volunteers from Shorov’s unit climbed to the top of the still burning building, raising an Abkhazian flag bearing the inscription of the Karbarda Battalion.

It was 12.50 pm. The battle for Sukhumi was effectively over.

There was one last act of violence left to take place. As Shorov’s men led Sharteva and the surrendered defenders out of the Council of Minister’s building, they ran into a mob of Abkhazian soldiers who had just arrived, having missed the fighting. At the sight of Sharteva and the others, these Abkhazians grew angry, and closed in on Shorov and his men, surrounding the Georgian prisoners, shouting words of abuse, and striking them with their fists and weapons. Shorov was told that the Abkhazians were going to take custody of the prisoners, and vehicles were summoned to take them away.

The situation was rapidly getting out of control. Georgian soldiers were knocked to the ground, kicked, and punched. Abkhazian soldiers began firing their guns into the air, their passions inflamed. Guns were turned on the soldiers, and three fell to the ground, dead. The vans arrived, and Shorov led the survivors into the vehicles. Abkhazian soldiers punched the Georgians through the open window as they were driven a short distance away, out of sight of the Council of Minister’s building, where they disembarked, all the while being beaten by the Abkhazian soldiers. Sharteva pled for the lives of his fellow prisoners, telling the Abkhazians that the terms of their surrender guaranteed their safety. The Abkhazians ignored his pleas, and without warning opened fire on the surrendered men, killing them all.

The bodies of Georgian prisoners murdered by Abkhazian soldiers, September 27, 1993

From his post guarding the northern approach to the Kelasuri River bridge, Bidzina and his fellow academicians could hear the battle rage from the center of the city, several miles away. Civilians continued to flee the fighting, a veritable flood in the morning, when it became clear that the city was falling, and then slowing down to a trickle as the morning turned into afternoon. The gunfire began to abate, the sustained staccato of automatic weapons fire being replaced by the odd, angry shot as the advancing Abkhazian forces dispatched Georgian stragglers, military and civilian alike (more than a thousand Georgian civilians were killed in this manner—to be caught outside was a death sentence; to try and hide in an apartment or basement was a death sentence delayed.) The bloodlust that was evident with the torture and execution of Sharteva and his men infected the hearts and minds of the Abkhazian victors. No mercy was being shown to the Georgian population that stayed behind—even old friends turned on their long-time neighbors, killing them without mercy.

The Abkhazian forces spread through the city, reclaiming locations that had been denied to them for more than a year. The Sukhumi promenade, where Marina and I had often walked together, fell under their control, along with the beachside restaurant that served delicious kebab and fresh bread baked in an open brick oven. So, too, did the corner café where Marina and her friends would entertain themselves—and me—by discerning their fortunes in the shapes produced by upending cups of Turkish coffee. One by one, the salient features of the beautiful seaside city were lost to the Georgians who called it home.

Bas-relief sculpture in the Sinop Park, Sukhumi

Once the center of the city was secure, Abkhaz troops began to advance down the highway leading south, toward Bidzina and the Kelasuri Bridge. They passed the Sinop Sanitarium, home to the Sukhumi Institute of Physics and Technology. In the aftermath of the Second World War, the Soviet Union took into custody hundreds of leading German scientists, including several who had been working on nuclear physics. These Germans were brought to Sukhumi, where they were put to work developing methods for uranium isotope separation, along with other highly technical problems, some related to Soviet research into nuclear weapons, others purely for the benefit of science. The Germans left in 1949, but the institute remained until early 1993 when, because of the war, its work was relocated to the Georgian capital of Tbilisi.

The institute maintained a lovely park, sort of a miniature botanical garden, between the highway and the buildings of the Sinop Sanitorium.

It was here that I proposed to Marina, and it was here where she said yes.

And it fell to the Abkhazians.

Next came Public School Number 19, named after Vadimir Komarov, a Soviet cosmonaut. In 1964 he commanded the Voskhod 1 mission. With a crew of two, Voshkod 1 was the first manned space mission to carry more than one crewmember. Komarov also became the first cosmonaut to fly into space flight, serving as the test pilot for the Soyuz 1 mission. A parachute failure of reentry led to a crash that took Komarov’s life, giving him another “first”—the first man to die during a spaceflight. Located less than 200 meters from the apartment building where Marina was raised, School 19 was the center of her childhood existence. Now it, too, was lost to her and the other students who had studied there over the years.

Marina’s apartment building—her home—fell next. Her family had hosted me there in the summer of 1991, and I had the opportunity to meet Marina’s neighbors and friends, a tight group of people who had the kind of bonds that only came through close, continuous contact over the course of many years. The apartment was built in the 1960’s, during the time of Khruschev, and was part of a category of prefabricated housing known as khruschevka. It had been renovated in the 1980’s with the addition of a balcony which allowed for the expansion of the kitchen and dining room. Marina’s home was furnished with heavily lacquered wood furniture from Romania, hand-picked by her mother, Lamara, which rested on fine rugs that covered the kind of wooden parquet floors typical of Soviet homes. The apartment was filled with the fine touches that transform a simple space into something simultaneously comforting and beautiful—a cut-crystal vase here, a painting hung on the wall there. It was the kind of home anybody would be happy to live in, a tribute to the Georgian homemaking skills of Lamara.

And now it was gone.

Looking back in time, with more than three decades buffering my memory, I still get emotional thinking about Sukhumi and what Marina and her family lost. My love for the city was born of barely a month’s experience. I can’t imagine what Bidzina must have been thinking, waiting for the Abkhazian forces to arrive—a lifetime of memories and experiences, flashing before him over the course of a few hours. The finality of the moment was obvious, but to finally realize that all was lost had to be heartbreaking.

Behind his apartment building Bidzina kept a small garage, where he parked the family car, a white Lada, and kept his prized hunting dog, a German shorthair named Chalk. Once the war began, Bidzina relocated Chalk to his Merkheuli garden to avoid the stress caused by the constant shelling of the city by the Abkhazians. Unfortunately, Chalk fell victim to a pack of wild dogs while Bidzina was off guarding the Kelasuri bridge—another tragic casualty of the conflict.

Marina and her parents, Lamara and Bidzina, with Chalk, in Merkheuli, July 1991

The white Lada was Bidzina’s pride and joy. He used it to go hunting and fishing, and to drive his family to destinations close and far. When I visited, Bidzina would drive me to Merkheuli while Marina taught her students. One weekend, he put Marina, Lamara, and me in the Lada, and drove us deep into the Svanetti highlands. We kept going until the road had become too narrow, creating a life-ending risk if we were to confront a logging truck coming down the road. Bidzina gingerly turned the Lada around and drove his much-relieved passengers back to the safety of the Sukhumi shoreline.

After the Abkhazians broke the ceasefire, in mid-September, trips into the city center became very risky. Bidzina made only one such foray, a few days before the city fell, to drive the mother of a neighbor who had been unable to get out before the airport was closed to the Sukhumi port, where she and thousands of other desperate Georgian civilians were evacuated on ships operated by the Russian Navy. The city was being shelled on a regular basis during this time, making a drive into the city a literal game of automotive Russian roulette.

This was the second rescue that the Lada had facilitated. In June 1993, Bidzina had received a frantic communication from a cousin, informing him that her 16-year-old son had fled Tbilisi to fight in the war. When Bidzina learned of the boy’s whereabouts, he once again braved Abkhazian artillery fire to drive to the front, where he found the boy, took him into his custody, and got him on a train heading home. This act probably saved the boy’s life, as the unit he had joined suffered heavy casualties in the fighting that took place in September.

On September 27, the Lada was parked on the southern end of the Kelasuri Bridge, behind a concrete building that had served as a passport control office before the war. Bidzina had loaded the vehicle with the most valuable family possessions, including his prized hunting gun, a German-made over-under combination gun consisting of a smooth bore barrel that used 20-gauge shotgun shells, and a rifled barrel chambered for 6.5×52mm ammunition. The Lada was fully fueled just in case it was needed.

That time was fast approaching. When shots rang out from the direction of the university grounds where Bidzina had taught, he and the few remaining men from the Sukhumi Company decided to withdraw to the other side of the bridge, where they could take up more defensible positions while still being able to provide covering fire for any civilians still trying to escape from Sukhumi. A few stragglers made their way out after the main battle in the city center had ended, and for more than an hour no one approached the bridge coming out of the city.

Then, in the shadows cast by the buildings on the other side of the Kelasuri River, Bidzina could make out the forms of men advancing, slowly, hunched over in the fashion of a soldier. One of Bidzina’s comrades opened fire, and the figures went to ground, before returning fire, causing the air above Bidzina’s head to snap with the sound of a bullet passing by. Bidzina and the other guards were not frontline soldiers, and they had only been issued four magazines of ammunition—120 rounds—each.

For the entire period of the conflict, none of the Kelasuri guards had cause to fire their weapons. Now, with the enemy closing in on them, they did so with abandon. Bidzina, the experienced hunter, cautioned the others to preserve their ammunition, firing only when a target presented itself. But a lack of training and adrenaline got the better of them, and one by one, the defenders of the Kelasuri Bridge exhausted their ammunition. Like Bidzina, each of them had parked a car nearby, and soon they began to make their way away from the bridge, singly and in pairs, to make good their escape.

Soon Bidzina was by himself, literally the last defender of Sukhumi. He had one magazine left—30 bullets. He waited until he detected some movement across the river, and then pointed his weapon, pulled the trigger, and kept firing until the magazine was empty. He then crawled to the passport control building, climbed into his Lada, and quickly drove away from the Kelasuri Bridge and the city he so loved, heading to his Merkheuli garden. From there, Bidzina would follow the road east, into the Upper Kodori Valley and safety. He had travelled this path often, on his way to hunting and fishing trips. The past excursions had been for pleasure; this time it was a matter of life and death.

One other option available to Bidzina was to drive 20 miles down the coast, to Dranda airport. But the airport was no longer an option. On September 21 a Тu-134 was flying to Sukhumi from Sochi International Airport when it was hit on approach by a surface-to-air missile fired from an Abkhazian boat. The plane crashed into the Black Sea, killing everyone onboard—six crew members and 22 passengers. The next day, September 22, a Tu-154 enroute to Sukhumi from Tbilisi carrying 132 persons—a mix of civilians and soldiers—was hit by a surface-to-air missile. The pilot managed to crash land the aircraft onto the airstrip, but the plane caught fire, killing 108 persons. A second Tu-154 was fired on later that day but managed to land unscathed. On September 23 a Tu-134 aircraft was in the process of boarding passengers for a flight to Sukhumi when it was struck by Abkhaz 122mm artillery rockets, killing one crew member, and destroying the aircraft.

Georgian refugees trapped at the Dranda Airport, September 1993

The airport was closed after that incident. Only one more flight would depart Dranda; in the early morning hours of September 28 a Tu-134 carried Eduard Shevardnadze, members of his cabinet, his security team, and scores of wounded Georgian soldiers to safety in Batumi. Thousands of Georgians who had fled Sukhumi to Dranda Airport, where they hoped to be able to catch a ride on an airplane that could fly them out of Abkhazia, were left stranded. With the Abkhazian forces closing in on both sides, these unfortunate people had no choice but to join Bidzina and thousands of others in the Kodori valley, their last available escape route.

When he arrived in Merkheuli, Bidzina found his garden plot occupied by Georgian soldiers and fighters from the Mkhedrioni. They were mounted on armored vehicles, were well-armed, and looked to be in good shape. Geno Adamia, the commander of the Sukhumi garrison, was trying to rally them to join him in heading back down the mountain to conduct a counterattack against the Abkhazian forces. But the Georgian soldiers and the Mkhedrioni militia had had enough of fighting. Geno Adamia was only able to gather a small band of 14 soldiers, who made their way back to the Kelasuri Bridge. There, on the morning of September 28, they tried to cross the bridge. The Abkhazians left their bullet-riddled bodies to rot in the sun and be eaten by dogs before finally burying them days after they fell.

Bidzina left the soldiers in Merkheuli, and drove up the valley, picking up passengers along the way, until he was stopped outside the village of Chkhalta, the hometown of Emzar Kvitsiani, an ethnic Svan who, prior to the Abkhazian conflict, made a living running illegal casinos throughout Abkhazia. Kvitsiani organized a local Svan militia of several hundred men named “Monadire” (“the Hunter”), ostensibly to defend the valley against any Abkhazian intrusions. But now, with Sukhumi fallen, Kvitsiani and his Svan militia instead set up a roadblock leading into the village, where they robbed the Georgian refugees as they passed through.

The Svan militia stole Bidzina’s white Lada, his family possessions, and his prized hunting rifle. Bidzina and his passengers were left to proceed on foot. It took them another day to make it to Sakeni, home of alluvial gold ore which, in ancient times, was mined by passing the running river water through a sheepskin—the source of the legend of Jason and the Argonauts’ “Golden Fleece.”

The journey to Sakeni was difficult, sapping the strength of the most physically fit of the refugees. For the elderly, the children, and women, the journey often proved too much, and the trail was littered with the bodies of those who could take no more. Bidzina was able to secure a small bag of sugar from the Svan militia and would mix a pinch with water as a way of keeping his energy up—a hunter’s trick. He met several of his neighbors and colleagues along the way who had become too weak to continue. Bidzina would prepare some sugar water, and have them drink it, allowing them to continue and, in doing so, probably saving their lives.

There were those he could not save, children left on the side of the road, too weak to continue. Bidzina would pick them up and carry them, only to come across another, and another.

A man has only two arms.

The worst moment came when Bidzina had to leave the road, and make his way through the Chuberi pass, a 50-mile stretch of rugged mountain terrain. Making matters worse, the weather had taken a wintry turn, with heavy snow falling as he began his trek. As the night dragged on, Bidzina would work his way around snow-covered boulders and logs, only to find that they were the bodies of those who had succumbed to the rigors of the trail.

The Georgian poet, Guram Odisharia, Guram, himself a citizen of Sukhumi, experienced the horror of the Chuberi crossing, and years later wrote about it in a book entitled The Pass of the Persecuted.

“They are coming and coming and there seems no end to the stream,” Odisharia wrote. “I see marauders, corrupt, soulless military functionaries branded by the blood of war, a sunflower seed seller and a millionaire with a narrow forehead, who has already become a pauper.” Odisharia likened the mass of humanity struggling to cross the pass to “fluttering autumn leaves,” their lives just as fragile as the objects caught in a mountain breeze. “It was perhaps the most terrible night on the highest point of the Sakeni-Chuberi pass,” Odisharia declared. “It was during that night that I saw several people die in my arms like birds.”

Georgian refugees trek through the Chuberi pass, October 1993

Thirty years ago, Bidzina Khatiashvili emerged from the southern slopes of the Greater Caucasus mountains, alive. Tens of thousands of Georgian refugees from Sukhumi made that dreadful trek, and hundreds lost their lives. Unlike most of his fellow Georgians who survived the harrowing journey over the Chuberi Pass, Bidzina had family in America. By the middle of November, he had obtained a visa and was able to fly to New York City, where he began a new phase of his life.

While Bidzina made several trips to Georgia in the nearly three decades that followed, he never returned to Sukhumi, and for the rest of his life Bidzina cursed Vladislav Ardzinba and those Abkhazians who stole his home from him and his family.

He never forgave Russia for its role in perpetrating the ethnic cleansing of more than 200,000 Georgians in Abkhazia.

But he also cursed Eduard Shevardnadze, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, Jaba Ioseliani, Tengiz Kitovani, Loti Kobalia, and a host of his fellow Georgians whose nationalistic hubris, brutality and incompetence sealed the fate of the city, people, and land he loved.

“What are we to do? What path are we to take?” Guram Odisharia’s words cry out from the pages of his book, The Pass of the Persecuted. “How can we help the dying child, quiet in his father’s arms, still breathing, before whom we are all guilty, the whole world, the whole Georgia, each one of us is guilty!”

Advertisement for the movie Lisa, Go On

War is deeply personal and is defined not only by the circumstances of the experience, but also the psyche of those who experienced it. I know for a fact that Bidzina desired nothing more than to be able to return to Sukhumi and the home—and homeland—he loved. Given this, I think he might have appreciated the intent behind Lisa, Go On.

But knowing Bidzina as I did, I don’t believe he could find it in himself to cast blame for the tragedy that befell the citizens of Sukhumi back on them. It wasn’t the citizens of Sukhumi who, in mid-September 1993, violated the July ceasefire after luring the children of Sukhumi back into their city in time for school to start on September 1. An attack like the one perpetrated by the Abkhazians and their allies takes months to plan and prepare for. The Abkhazians knew what they were doing when they created the illusion of peace they wanted the women and children of Sukhumi to suffer.

In an article written a week after the premiere of Lisa, Go On, Nana Janelidze noted that it is important for all parties to analyze what happened regarding the war. “We should not be afraid of our mistakes,” she wrote, “we should not be afraid to make the first step and apologize.”

I struggle to find anything in Bidzina’s experience that is worthy of an apology being issued by him. In many ways, Bidzina and the citizens of Sukhumi are the real victims of the Abkhazian war, caught in the middle of a power struggle which could only be resolved with them either losing their lives, or losing their homes.

Bidzina’s only crime, it seems, was, like tens of thousands of his fellow Sukhumi residents, refusing to die. Their continued existence stands as a constant reminder of the injustice done to them by all parties to this conflict. So, too, does their collective history, which can never be forgotten, especially in a time when historical revisionism is all the rage.

Thirty years ago, the city of Sukhumi fell to Abkhazian separatists.

Hopefully all the parties to this conflict can find it in their collective hearts to forgive one another.

But we should never forget that which demands forgiveness.

Bidzina was a man of many great accomplishments. I am convinced that, in his own mind, his greatest feat was, in his sixth decade of life, standing guard over the Kelasuri Bridge, defending his home, his neighbors, and his beloved Sukhumi from those who wished them harm. And his biggest regret is having to abandon his post in the face of an overwhelming enemy, sealing the fate of those who, like him, were condemned to escape through the Chuberi pass.

Bidzina passed away in his sleep on the night of January 2, 2019. He was 88 years old. In the hours before he passed, Bidzina slipped in and out of consciousness. He spoke of joining his old comrades on a glorious hunt in the mountains of Abkhazia. But he also spoke of a dream, about a bridge, and men fighting.

Some memories fade away over time.

Some nightmares never go away.

joseba says:

Scott Ritter@RealScottRitter

Scott Ritter Extra Ep. 104: Ask the Inspector

https://twitter.com/i/broadcasts/1BRKjPpWZojJw

joseba says:

https://jam-news.net/film-go-lisa/

Georgia

01.10.2023

“Liza, Go On” – a movie about the war in Abkhazia and why it caused such a strong reaction

Share facebook twitter messenger vk-black email copy print

Film, Liza, Go On

A new film, “Liza, Go On”, about the war in Abkhazia is in Georgian theaters. The movie tries to show the truth about the opposing sides. “If we don’t confess and repent, we won’t get anything back” – the movie says.

Part of the audience criticized it. They believe that Georgia is portrayed as guilty, the cruelty of Georgian soldiers is emphasized and the memory of war heroes is insulted.

Photo archive: Georgian families leaving Abkhazia during the 1992-1993 Georgian-Abkhaz war

Georgian-Abkhaz war, 1992-1993

Abkhazians and Georgians – what do they say about each other in literature? Guram Odisharia video

Opponents of the movie equated it with Russian propaganda and called it a Russian special project. They contacted the ruling Georgian Dream party, which financed the filming, and stated that the purpose of the movie was to strengthen the Russian version of the war in Abkhazia.

The emotions and assessments of displaced people from Abkhazia were particularly intense. Some of them took the apology to Abkhazians painfully.

“The victim does not apologize. Before whom should we apologize, those who kicked us out of our homes?” – they ask.

Another part of the audience, however, considered the movie a brave attempt to start rethinking the war, to learn the previously unknown truth and undergo a transformation, as it happens to the main character of the movie.

Film Liza, Go On

What the movie is about

Liza, the protagonist

“It was as if I knew everything about the war, but what Abkhaz said was like a slap in the face,” says the protagonist of the movie, a journalist who worked as a reporter during the war. She is now a well-known TV presenter, but the experience of the war remains with her.

One day an Abkhazian soldier calls her on the program she is broadcasting live, and this turns out to be a turning point for Lisa. The heroine begins to have an internal conflict. Lisa gets into a car and sets off on a long journey, not knowing where she is going.

When the Georgian-Abkhazian conflict was closest to resolution – panel discussion & video

Conflictologist Paata Zakareishvili on the missed chance to avoid war and how to look for a solution today

The script of the movie is based on the real experience of a war reporter. The screenwriter Lia Toklikishvili covered the war in Abkhazia for one of the first independent newspapers in Georgia. According to the director Nana Janelidze, Lia is the author of the movie.

The movie uses stories and diaries of participants and witnesses of the Georgian-Abkhazian war, Georgian and Abkhazian writers and clergymen. The director says that the narratives of the participants of the war were so horrifying that it would have been impossible to show them with the help of movie frames. That’s why they decided to use animation, partly by Georgian and partly Ukrainian artists.

The movie is a co-production between Georgia and Bulgaria. The film was made with the financial support of the National Film Center and the Ministry of Culture over eleven years. The cost of the film amounted to about 1.7 million GEL (about $633,000).

Film Liza, Go On

What was the reaction to the movie

The release of the film in Georgian theaters coincided with several important events: the war in Ukraine, after which Georgia began to review the conflicts in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, the 30th anniversary of the war in Abkhazia and the events in Karabakh, which revived the theme of the military return of Abkhazia.

“Why Abkhazia does not face the fate of Nagorno-Karabakh?” Opinion

Inal Khashig discusses why, in his opinion, Russia will not leave Abkhazia without military support if necessary

Discussions with the film’s authors are being held after the screenings. One of the screenings, which took place on September 27 – the date when Sukhumi came under the control of Abkhazia in 1993 – elicited indignation in part of the audience.

“Betrayal”, “Russian propaganda”, “insult to Georgians” – such terms were used by those who were angered by the movie, mainly forced migrants from Abkhazia. The discussion scheduled for that day did not take place.

“This movie is ussian propaganda,” former Georgian President Mikhail Saakashvili, who is currently in prison, wrote on social media.

Culture Minister Thea Tsulukiani, who has repeatedly criticized the film’s director Nana Janelidze, also reacted to the film. The Minister called the movie a “setup”.

Film Liza, Go On

Why the film was criticized

Photo: official Facebook page of the movie.

Those who were outraged by the movie say that Georgian soldiers are portrayed as marauders and the Georgian state as a murderer, scoundrel and traitor. In their opinion, the emphasis in the movie is more on crimes of Georgians than Abkhazians, and everything is presented as if Abkhazians were defending their homeland from invading Georgians, for whom it was just a territory. They also challenge the accuracy of facts. They say that for foreign viewers this is a movie about Georgians and Abkhazians killing each other, and it is unclear what Russia has to do with it.

“This is not only a fiction movie, but also a documentary, so it is necessary to give accurate facts,” says journalist Vakho Sanaya.

The most emotional criticism was given to the idea embedded in the film that Georgians should ask forgiveness from Abkhazians.

“Where is it seen that victims of ethnic cleansing ask for forgiveness! I do not know such a precedent”, Vakho Sanaya asks.

Disgruntled viewers after watching the movie also spoke about it:

Zaza Bibilashvili, founder of the civil organization Chavchavadze Center said: “There was genocide, ethnic cleansing in Abkhazia, and this happened after the ceasefire agreement was concluded. And in this light, talk that we did something wrong and should apologize is mimicry.”

Mshibzia flashmob resembles a ‘rahat loukoum’, proposed by Georgians to Abkhazians

It has nothing to do with respect for the Abkhazians’ rights

Georgia has once before run a similar campaign of apology to Abkhazians. In 2016, it was launched on social networks by a group of young people who put the word “Mshibzia” (Abkhazian for “hello, peaceful day”) on their avatars. However, the action did not meet with a positive reaction from Abkhazia.

“For me apologies are not a mandatory component, I am not in favor of it, but I am not against it either,” conflictologist Paata Zakareishvili, who generally liked the film, says.

In his opinion, the apology should be a political action:

“Georgian-Abkhazian reconciliation should reach the level where the parties understand that it would be good if we apologize to each other now. There should be an understanding that we cannot move forward without it.”

Film Liza, Go On

Arguments of those who liked the movie

“Each of us has our own information about what happened in Abkhazia, and this information often does not coincide. This movie forces everyone who is interested in what happened in Abkhazia to once again delve into and understand. Many thanks to the state for this [we remind that the movie was made at the expense of the state – JAMnews],” Paata Zakareishvili said

According to him, it is not difficult to find donors for such a movie, but the fact that the state financed it means that it is ready for dialogue, ready to start discussing sensitive issues.

Paata Zakareishvili believes that for the part of viewers who criticize the film, the distinction is very superficial – be it a Georgian-Abkhazian or Georgian-Russian conflict. In fact, it is not so, because “the conflict does not have one level”:

“Yes, the number one problem is Russia’s imperialist war with its neighbors. But this war is fueled by localized problems in one region or another. We need to understand this. The second level is internal problems, Georgian-Abkhazian, Georgian-Ossetian. Third is the Georgian-Georgian conflict, which we see by reacting to this movie. And fourth, the man inside the conflict. The main merit of this movie is that it depicts the inner conflict of a human being.”

“This film makes us think about the scale of conflicts,” Tamta Mikeladze, head of the Center for Social Justice, says, who believes that the conflict cannot be explained by the Russian factor alone.

“As actors working on peace issues, we recognize Russia’s strong influence, but we say that it is important to work on internal ethno-political issues, to listen to Abkhazians, to dialogue with them and recognize mistakes. Unfortunately, political players do not take this dimension into account, they believe that Abkhazians should not be considered as a party to the conflict at all.”

What was shown in the movie?

“As expected, on the thirtieth anniversary of the fall of Sukhumi, another hysteria has gripped us. Any bold idea of solving the Abkhazian issue is declared a betrayal (or at least blasphemy). This will be the case until a consensus on the Abkhazian issue is formed in Georgian society and we agree on a number of fundamental issues,” political scientist Tornike Sharashenidze says.

According to Tamta Mikeladze, reaction to the film shows that society is not ready to discuss conflicts from different points of view, listen to different opinions and come to an agreement through dialogue.

According to her, it is necessary to prepare for dialogue by opening archives, processing data, building a dialogue between professional, political, civil organized groups, thoroughly processing the views of the population affected by the conflict and involving them in the dialogue. The state is doing none of this.

“This movie has once again intensified the discussion on the internal dimensions, created space and stimulated important discussions. I believe the movie achieved its goal. The director knew what she was doing.”

Director of the movie Nana Janelidze at a discussion after a screening of the movie. Photo: Official social media page of the movie

“While working on the movie, I knew that it would cause controversy and disagreement, make noise. This is the mission of this movie – to awaken the dulled pain, to think, argue and look for a solution together (!),” director Nana Janelidze wrote a week after the premiere.

She writes that it is necessary to analyze what happened: “We should not be afraid of our mistakes, we should not be afraid to make the first step and apologize. Otherwise we, as a nation, a country, a state, will not be able to continue our life, this silence will hold us back, will not allow us to move forward… We must express our opinion, and then Abkhazians will also have the courage to express theirs”.

According to the director, the movie “Go, Lisa” gave the Abkhazian theme a new urgency: “It turned out that everyone is concerned about it, although no one has a real understanding and a plan for a solution: neither the artist nor the politician.”

“The existence of the movie is important, it was made, it was released and it cannot disappear. If you understand this movie, you will understand a lot,” adds Paata Zakareishvili.