Niel Wilson

Moneta-Teoria Modernoa

Hasiera gisa, ikus ondokoak:

Errusiaren gaineko zigorrak eta MTM

Segida:

Transakzio orokorra: NOK, GBP, USD

(a) Niel Wilson-en Anatomy of an FX Transaction

(https://new-wayland.com/blog/anatomy-of-an-fx-transaction/)

27 Dec 2020

An FX transaction between floating rate currencies is actually two contracts. One is Bank A putting Bank B in credit with Currency A, and the other is Bank B putting Bank A in credit with Currency B. These contracts are assets of the banks, which can then be discounted into the currency the bank operates in. That creates the matching liabilities, which are deposits and which can then be used to pay people in the other currency area.

We can use this process to model how the currencies flow from the point of view of a net exporter in a free floating currency rate environment.

For example, a Norwegian Bank contacts a UK bank and agrees to a contract to purchase 100 GBP for, say, 1158 NOK. That price is just agreed like any other price for a contract. The ‘exchange rate’ is just the banks shopping around between each other.

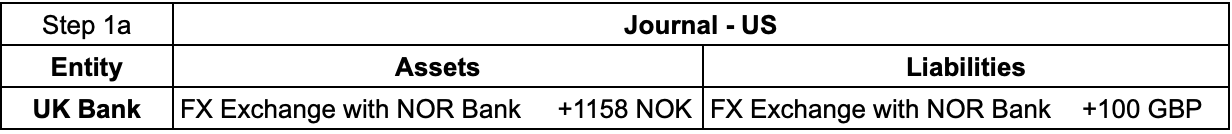

The Norwegian bank now has a contract from the UK Bank to credit it 100 GBP. The UK Bank similarly has a contract from the Norwegian Bank to credit it 1158 NOK

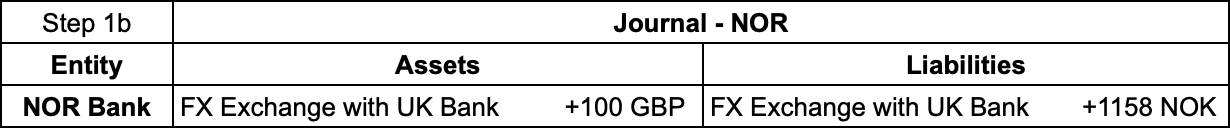

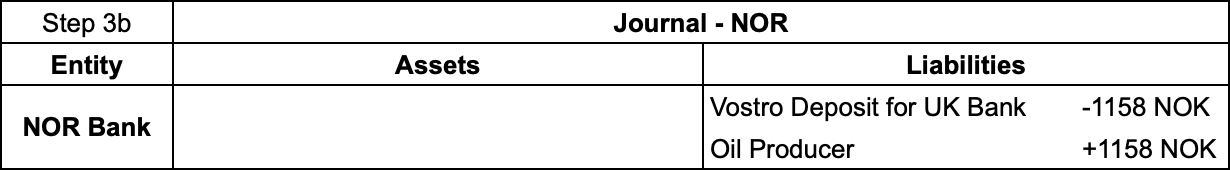

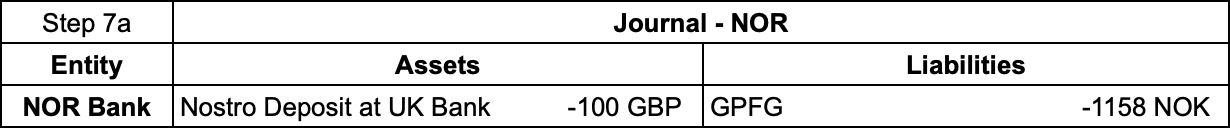

The Norwegian Bank takes the 100 GBP contract asset and discounts it to 1158 NOK on its books (marks up the liability out of nothing) and then credits the account of the UK Bank at the Norwegian bank with that 1158 NOK – fulfilling its side of the contract.

The UK Bank takes the 1158 NOK contract asset and discounts it to 100 GBP on its books (marks up the liability out of nothing) and then credits the account of the Norwegian bank at the UK Bank with that 100 GBP – fulfilling its side of the contract.

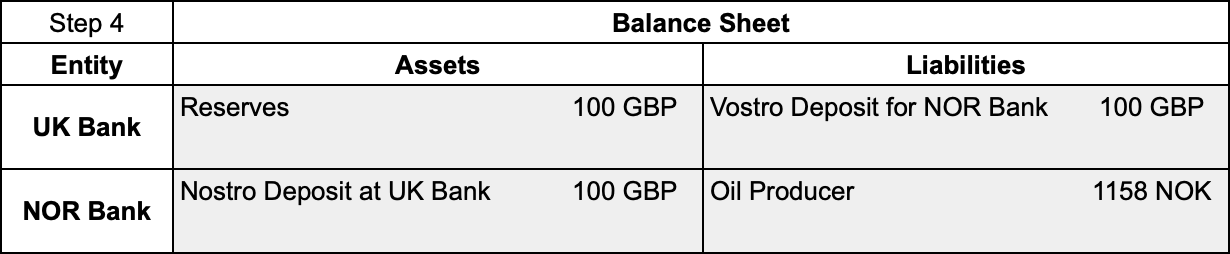

The contract assets are now replaced with deposit assets in the other bank. The Norwegian bank has an account with the UK Bank with 100 GBP in it and the UK Bank has an account with the Norwegian Bank with 1158 NOK in it. The balance sheets all balance.

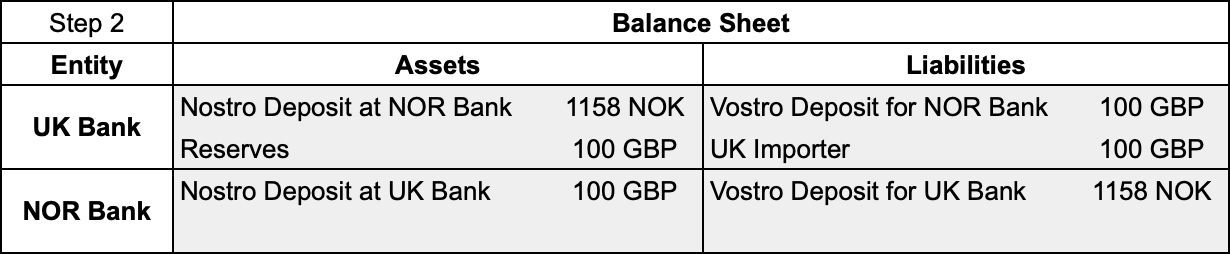

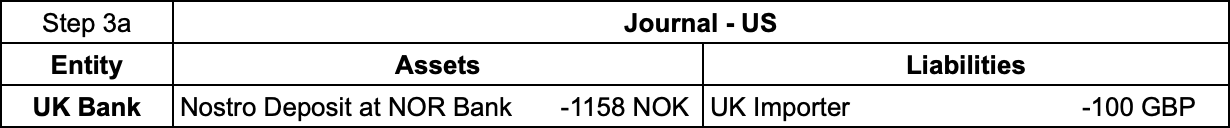

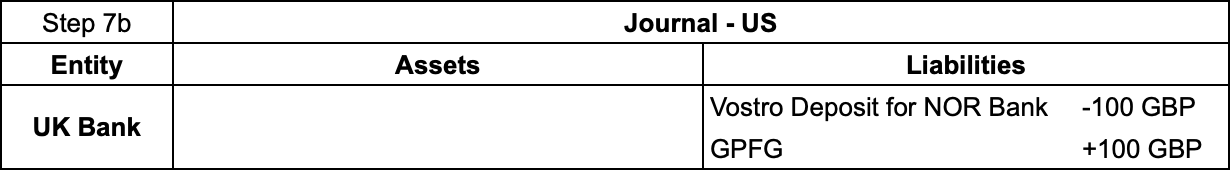

A UK importer hands over their 100 GBP and asks their bank to pay a Norwegian producer for a consignment of oil. The UK Bank deletes the (additional) 100 GBP deposit the UK importer holds and then contacts the Norwegian bank and asks them to transfer the 1158 NOK to the credit of the oil producer.

The result is a Norwegian Bank with a 100 GBP deposit, who gets a statement from the UK bank showing which account their pounds are in.

Note that either the Oil importer in the UK does the FX, or the oil supplier in Norway does the FX. Either way it has to be done to pay people in Norway, who want to receive NOK, not GBP. Similarly although oil may be priced in USD, the transaction here is GBP to NOK. That’s because customers desire to pay in the currency they have and suppliers desire to receive the currency they wish to hold. The financial system gets paid to make that desire a reality and selling in a local currency increases sales. The currency something is priced in isn’t necessarily the one it is invoiced in, or settled in – at either end of the deal.

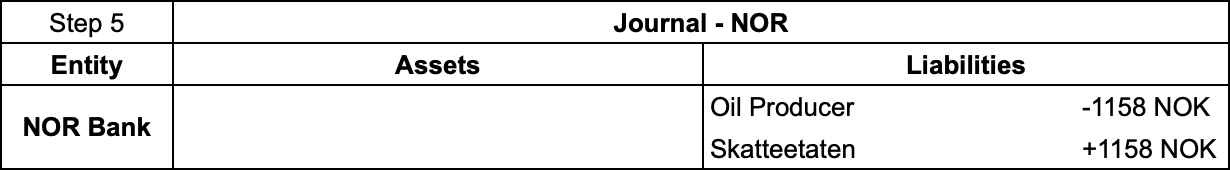

The Oil Producer pays their staff, their suppliers and their investors in NOK.

The Norwegian state then taxes those flows in NOK as they bounce around the economy. Let’s assume the Norwegians are in a spending mood and over a series of transactions all the money becomes taxation.

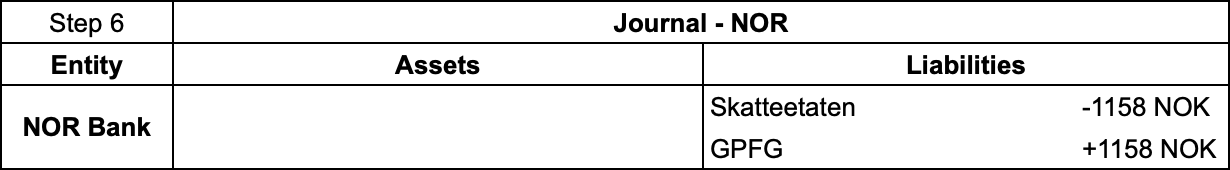

The policy of the Norwegian government is to pass onto the Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG) taxation arising from oil. (For convenience here assume that GPFG has an account at this particular NOR Bank. In reality there would be a set of inter bank NOK transfers to and from the Norges Bank where the GPFG and Skatteetaten hold their main accounts that would add nothing other than length to this post).

The net result is that the GBP deposit that was originally in the hands of a UK oil importer ends up, by a very circuitous route, in the hands of the Norwegian Government Pension Fund Global – ready to purchase UK financial assets.

And that is how a net exporter injects its own currency into its economy – via a touch of financial alchemy. The GPFG drains excess foreign currency from the Norwegian banking system and the Norwegian banks know that so are happier facilitating foreign transactions.

This process is common to all net exporters and comes in various forms from outright currency pegs where the central bank relieves the local banking system of its currency risk directly to leaving the banks to fend for themselves which tends to cause a drift towards ‘hard currencies’ – primarily the US dollar – that the banks are happy to hold as backing assets on their individual balance sheets for the local currency liabilities they issue against them.

What we can see is that although the process starts as money creation, the desire to get rid of currency risk pares that back to a simple exchange of savings. Somebody within the net exporter currency area has to end up as the saver of FX financial assets, and they are forced to be that entity or the currency rates will move to match the flow with the available quantity of savers. A currency rate move would be to strengthen the export currency and weaken the import currency – which destroys exports and therefore jobs in the exporting nation. The importing nation ends up with less stuff.

The choice, however, rests with the exporting nation – since they can bring their currency down by market intervention without limit. A smart importing nation would realise that and manage its relationships so that economic and political pressure in the export nation is brought to bear – rather than trying to buy foreign savers with needless interest payments. An approach that just exacerbates the problem rather than alleviates it – since the interest payment really needs to be saved.

Errubloak eta euroak: transakzioak

(b) Niel Wilson-en Rouble Gas Payments are probably a False Flag

(https://new-wayland.com/blog/rouble-gas-payments-false-flag/)

Rouble Gas Payments are probably a False Flag

28 Mar 2022

Much has been written about the Russian demand that Europe pays for its gas in Russian Roubles. Most of it is ill-informed and even the good stuff slightly misses the point.

What they miss is that in every single international transaction the consumer pays with the currency they have, and the producer gets the currency they want to hold. It is the job of the finance industry to make the match magic happen, for which they get handsomely rewarded.

What that means is Gazprom already gets paid in Roubles for the part of its operation that is based in Russia. How could it pay Russian staff otherwise?

Therefore, all that is likely to change once the edict from Putin is in place is that Gazprom will tend not to hold Euros, assuming it is doing so at the moment anyway. Given the confiscations of Russian assets going on I’d be amazed if the treasury department in Gazprom hasn’t already dumped any asset denominated in Western currencies. Arguably they’d be negligent if that hasn’t happened.

Banks transact internationally by finding a path of banking relationships around the world between the buyer and the seller. This process of hopping the transaction around is called correspondent banking and works very much like the routers on the Internet that move traffic around. It may look like you have a point to point connection with this blog site but in reality the page you are viewing has passed through maybe a dozen router’s hands before it gets to you. International bank transfers work in much the same way. Each bank pays the next down the chain until it gets where it needs to go. If the direct path is blocked, the payment will be routed elsewhere in the world until a path is found. Banks in ‘non-hostile’ countries stand to make a packet.

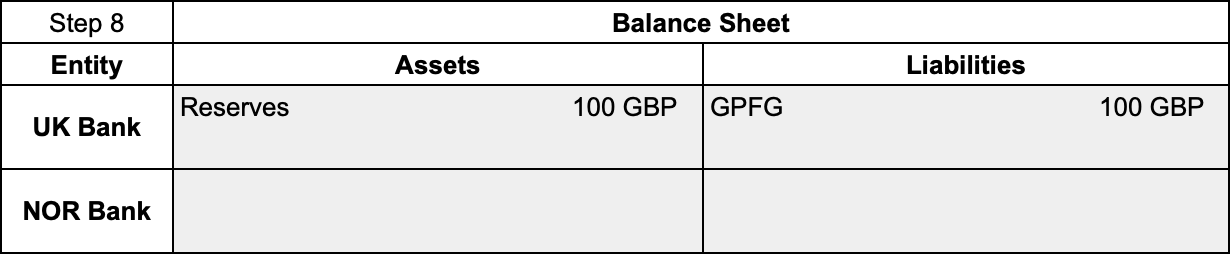

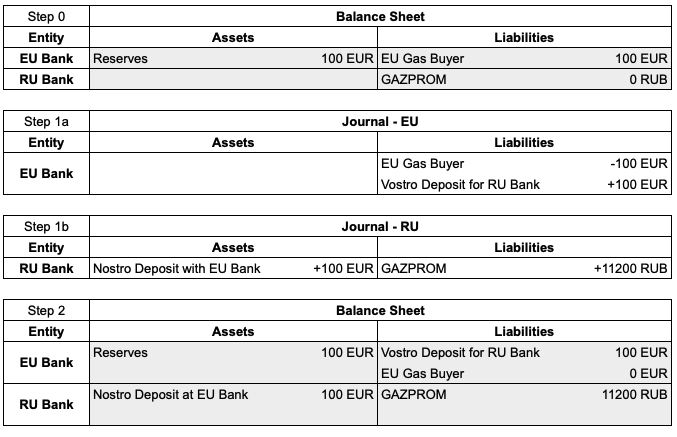

In all likelihood the normal situation was probably something like this:

Here the EU Gas Buyer pays Gazprom for their gas using Euros. The bank takes the payment and transfers it to the Russian bank account of Gazprom. Gazprom gets credited at the Rouble exchange rate quoted by the Russian bank and the Russian bank takes an FX position in Euros with the source EU bank.

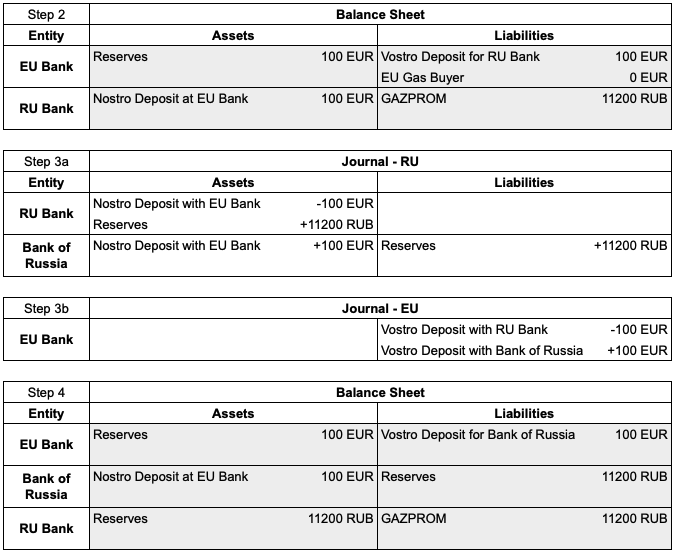

Now banks are notoriously risk averse in payments and the Russian bank will want to get rid of the Euro position as soon as it can. Up to now that has been rectified by the Bank of Russia taking the Euros and holding them itself – unusually with EU Banks rather than directly at the ECB.

Here the Bank of Russia takes the Nostro Euro deposit from the Russian Bank, with the EU Bank making an internal transfer in the Vostro mirror accounts to match. In return the Bank of Russia credits the Russian Bank with Rouble Reserves. (Probably the Bank of Russia will then Reverse Repo the deposit for a higher paying EUR financial asset).

What this shows is that the Russian government’s demand that everything is paid in Roubles doesn’t actually alter anything because Gazprom is being paid in Roubles anyway. The gas buyer will still be paying with Euros, with the banks in between earning a fat fee for shuffling the paperwork.

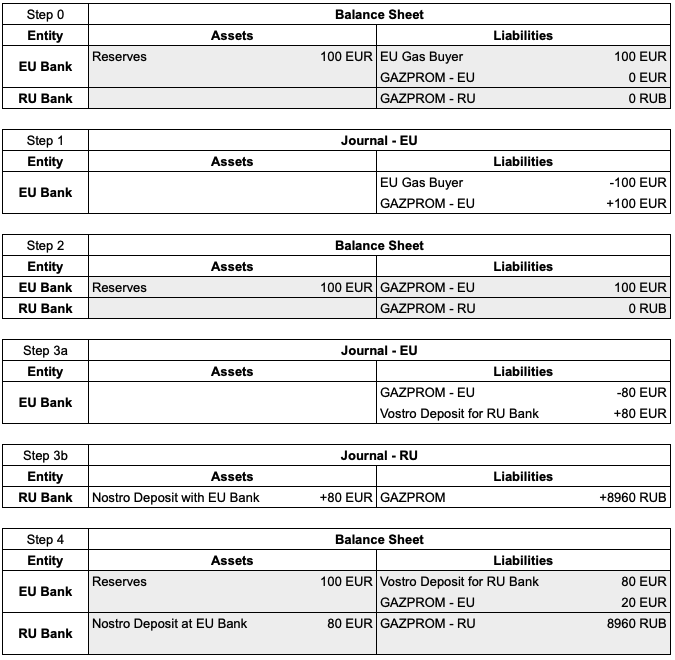

Now it may be that Gazprom wasn’t having all of its Euro income transferred to Russia. The current edicts only require 80% to be transferred to Russian banks, which looks something like this:

Here Gazprom first receives the Euros into its own account at an EU bank and then transfers some of that into Roubles in its Russian account. It may be that the new edict is a way of forcing Gazprom to stop holding Euros, while also creating political confusion amongst the majority of people who have no clue how international banking transactions are settled.

Having read this far have you spotted the issue that may just cause some fun? Remember that banks are very risk averse and don’t want to hold open positions in foreign currencies. If the Bank of Russia no longer offers to take Euros from Russian commercial banks, or no longer can due to sanctions, then the exchange rate offered by the Russian banks will be the one that allows it to get rid of its Euro position. In other words it has to be matched by a Rouble to Euro purchase going in the other direction. Except that sanctions mean little is currently going in that direction.

That’s a recipe for a very large appreciation in the value of the Rouble, or a full blown EUR-RUB liquidity crisis where Roubles can’t be obtained at any price. This may be another reason why Russia is demanding that future gas contracts will have to be not just settled in Roubles but priced in them in the first place. Shifting the exchange rate risk to the Europeans makes sense – because they are convinced that sanctions are going to make the Russian currency depreciate.