Yeva Nersisyan, L. Randall Wray – Are We All MMTers Now? Not so Fast

(https://braveneweurope.com/yeva-nersisyan-l-randall-wray-are-we-all-mmters-now-not-so-fast)

What is being conveniently presented as Modern Monetary Theory by governments to save corporations is in many ways quite different than the leading MMT scholars have advocated.

Yeva Nersisyan is an associate professor of economics at Franklin and Marshall College. Senior Scholar

L. Randall Wray is a professor of economics at Bard College

(i) DTMren desitsuraketa

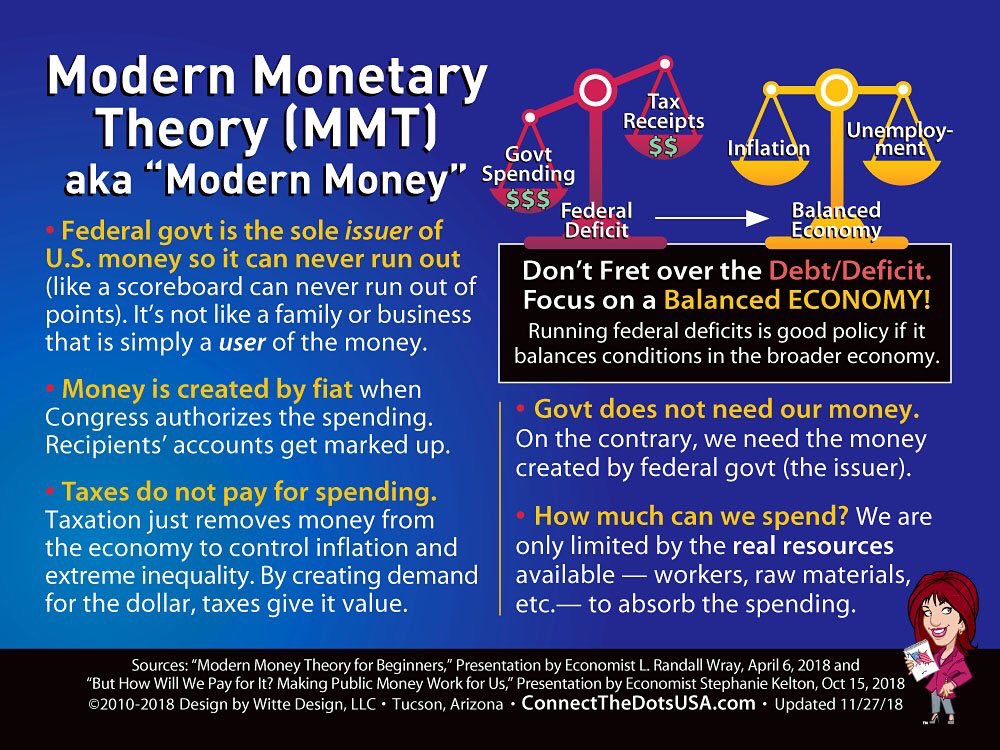

Modern Money Theory (MMT) has been thrust into the spot-light again, as numerous governments around the world respond to the pandemic. Unfortunately, those invoking MMT misrepresent its main tenets. For example, we are being told MMT calls for helicopter drops of cash or having the Federal Reserve finance government spending through rebooted quantitative easing.

This is not MMT, which provides an analysis of fiscal and monetary policy applicable to national governments with sovereign, nonconvertible currencies. It concludes that the sovereign currency issuer (1) does not face a “budget constraint” (as conventionally defined), (2) cannot “run out of money,” (3) meets its obligations by paying in its own currency, and (4) can set the interest rate on any obligations it issues.

Current procedures adopted by the Treasury, the central bank, and private banks allow government to spend up to the budget approved by Congress and signed by the president. No change of procedures, no money printing, no helicopter drops are required. Modern governments use central banks to make and receive all payments through private banks.

(ii) Prozedurak

When the Treasury spends, the Fed credits a bank’s reserves, and the bank credits the deposits of the recipient. Taxes reverse that, with reserves and the taxpayer’s deposit debited. This is all accomplished through keystrokes—something government cannot run out of. Both the Treasury and the Fed can sell bonds (in the new issue and open markets, respectively) to offer banks higher returns than they get on reserves.

As MMT explains, since reserves must be exchanged when purchasing government bonds, the reserves must be supplied first before bonds can be purchased. It demonstrates how the Fed provides the needed reserves even as it upholds the prohibition against “lending” to the Treasury by never buying the bonds directly. None of this is optional for the Fed. It cannot refuse to clear government checks, nor can it refuse the reserves banks need to clear payments. It is the government’s bank, after all, and is focused on the stability of the payments system.

(a) Gobernu, Kongresu era Fed-en rolak

Government can make all payments as they come due. Bond vigilantes cannot force default, although their portfolio preferences could affect interest rates and exchange rates. But the central bank’s interest rate target is the most important determinant of interest rates on the entire structure of bond rates. Bond vigilantes cannot hold the nation hostage—the central bank can always overrule them. In truth, the only bond vigilante we face is the Fed. And in recent years it has demonstrated a commitment to keeping rates low. In any event, the Fed is a creature of Congress, and Congress can seize control of interest rates if it wishes to do so.

(b) Altxor publikoa eta Kongresua

Finally, the Treasury can “afford” to make all payments on debt as they come due, no matter how high the Fed pushes rates. Affordability is not the issue. The issue will be over the desirability of making big interest payments to bondholders. If that is seen as undesirable, Congress can tax away whatever it deems excessive.

(iv) Baliabideen mugak, ez finantzarenak. Inflazioa, langabezia

What we emphasize is that sovereign governments face resource constraints, not financial constraints. We have always argued that too much spending—whether by government or by the private sector—can cause inflation. Below full employment, government spending creates “free lunches” as it utilizes resources that would otherwise be left idle. Unemployment is evidence that the country is living below its means. Full employment means that the nation is living up to its means. A country lives beyond its means only when it goes beyond full employment, when more government spending competes for resources already in use—which could cause inflation.

(v) Analogia faltsuak. Aurrekontua. Deflzita

MMT rejects the analogy between a sovereign government’s budget and a household’s. The difference between households and the sovereign holds true in times of crisis and also in normal times, regardless of the level of interest rates and existing levels of outstanding government bonds (i.e., national debt). The sovereign can never run out of finance—period.

MMT does not advocate policy to ramp up deficits. A bud-get deficit is an outcome, not a goal or policy tool to be used in recession. There is no such thing as “deficit spending” to be used in a downturn or crisis. Government uses the same procedures no matter the budgetary outcome—which will not be known until the end of the fiscal year, as it depends on the economy’s performance. The spending will have occurred before we even know the end-of-the-year budget balance

(vi) COVID-19-ren krisia

An important lesson to learn from the COVID-19 crisis is that the government’s ability to run deficits is not limited to times of crisis. Indeed, it was a policy error to keep the economy below full employment before this crisis hit in the belief that government spending was limited by financial constraints. Ironically, the real limits faced by government before the pandemic were far less constraining than the limits faced after the virus had brought a huge part of our productive capacity to a halt.

We hope this pandemic will teach us that in normal times we must build up our supplies, our infrastructure, and our institutions to be able to deal with crises. We should not wait for the next national crisis to live up to our means.

joseba says:

Don’t say its over until its over – MMT is not close to dominating the narrative

(http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=47555)

Don’t say its over until its over. There has been progress in the macroeconomics narrative since the GFC, which accelerated during the pandemic. Governments have certainly expanded fiscal deficits and taken on more debt and the usual hysteria, which many of those same governments helped to ferment in the public debate, has fallen away. Obviously, for political reasons, a government that has previously been terrorising the population about the dangers of deficits and rising debt as a cover for ideologically-driven austerity programs, has no incentive in continuing those narratives while they have been dragged into maintaining capitalism on life support. The question has been whether these narratives will return once the health emergency starts to fade a little. There is clear evidence emerging that the lessons that the pandemic has taught us are not being absorbed by the economics commentariat, who dominate the public space with their opinions. Two clear examples of this came out this week (already) in the Australian press, which replicates the sort of commentary I am increasingly seeing around the globe. Deeply sad.

Fundamental misperceptions about continuous fiscal deficits

The shift in narrative has seen economists and commentators suggest that this period of fiscal flexibility should only be temporary and then, at some time in the future, the usual ‘surplus’ is best narrative should resume.

The Economics Editor of the Melbourne Age and the Sydney Morning Herald, Ross Gittins published this article yesterday (May 24, 2021) – Why the government should ditch ‘stage 3’ tax cuts to repair the budget – which claimed that:

… most economists agree that at the right time, the government should take measures to hasten the budget’s return to balance, even – to use a newly unspeakable word – “surplus”.

As usual, I am in the minority of my profession.

Apparently, the difference now, as opposed to the GFC, when economists pressured governments to prematurely abandon fiscal support, which worsened the negative consequences of crisis, is that, according to Gittins:

… the right time will be when the economy has returned to full employment, with no spare production capacity.

So why is that the right time?

Because according to Gittins – inflation and wages growth will be on the cusp of accelerating outside safe parameters.

And, Gittins claims that:

Any further fiscal stimulus from a continuing budget deficit would risk pushing inflation above the target and could induce a “monetary policy reaction function” where the independent Reserve countered that risk by raising interest rates.

Note that a “continuing budget deficit” is characterised as “further fiscal stimulus”, which is really the problem with these narratives.

Gittins then reverts to the ‘forward looking’ mantra, which the US Federal Reserve has now abandoned, by claiming that it is:

… better for the government to act before the Reserve acts for it.

This approach has been dominant over the last three decades and always sees policy tighter than the circumstances in the real economy (employment, output, etc) would justify.

The problem is that the measure of full employment that has dominated this period is deeply flawed because it is biased towards equating elevated levels of unemployment with full capacity.

Gittins just channels the “econocrats’ best guess at the level of full employment – when unemployment is down to between 5 and 4.5 per cent” – without critical scrutiny.

This is the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment or NAIRU mythology.

Please read these blog posts (among others) for background:

1. Never trust a NAIRU estimate (May 13, 2020).

2. The NAIRU/Output gap scam reprise (February 27, 2019).

3. The NAIRU/Output gap scam (February 26, 2019).

4. Why we have to learn about the NAIRU (and reject it) (November 19, 2013).

5. NAIRU mantra prevents good macroeconomic policy (November 19, 2010).

6. The dreaded NAIRU is still about! (April 16, 2009).

There is no robust evidence that the unemployment rate of 5 per cent is the threshold between inflation being stable and accelerating.

The statistical/econometric techniques that generate these NAIRU estimates produce very imprecise point estimates with typically large standard errors.

They also tend to be just filtered versions of the actual unemployment rate and go up and down accordingly with no shifts in ‘structural’ parameters, the latter of which are claimed to generate shifts.

We see NAIRU estimates rising and falling with the economic cycle with no perceived shift in economic structure.

When econometricians use ‘structural’ variables to ‘explain’ these shift, we also see these variables, themselves are highly cyclically sensitive, meaning they cannot provide structural (non-cyclical) information.

So why does Gittins privilege these ‘limits’, which have no foundation in reality?

Well, because it is a convenient ruse that appears to be one of those technical constructs that evade public scrutiny, which gives it a sense of authority, that only people like me who have the training and the technical know how but not the ideology can critique.

Gittins aim in the article is to argue against proposed tax cuts in July 2024.

I have no problem with the view that we should wait until closer to the date to assess whether the tax cuts (or any fiscal setting) is appropriate to the context we find ourselves in at that point.

But the relevant word is CONTEXT.

Which is why the conceptual argument Gittins makes in the lead up to his discussion on the proposed tax cuts is poor and misleading.

To explain, context does not relate to the monetary size of the fiscal deficit or the level of public debt.

In stand-alone terms, those financial numbers have no relative meaning. We cannot make any assessments on the basis of someone saying the fiscal deficit is 10 per cent of GDP or 2 per cent.

The former is not better or worse than the latter.

A 2 per cent surplus is not better or worse than a 10 per cent deficit.

It all depends … on the context.

The government is just one spending source in the economy.

Taken together spending equals output equals income, which drives employment.

To have full employment, spending has to be sufficient to create output that, given productivity, can create sufficient employment to satisfy the desire for work from the labour supply.

If non-government spending (that is, the sum of household consumption, business investment and export revenue) is insufficient (which means that sector is saving a proportion of its income) to produce full employment, then the only way the economy can reach that desired employment level, is if the government meets the ‘spending gap’ by running a deficit.

This is not an opinion. It is basic national accounting.

So a continuous fiscal deficit is usually required to produce full employment, especially if the nation is running an external deficit.

A surplus in this context will drive the private domestic sector into continuing deficits, rising indebtedness, and ultimately, insolvency.

That is context.

A nation such as Norway, with very strong external revenue coming from its export sector can run a fiscal surplus and still ensure national income is sufficient to generate savings that satisfy the private domestic sector aspirations.

A different context.

So it is just plain ignorant for one to conclude that a fiscal surplus (in the Australian context) would be the appropriate position at full employment.

Such a fiscal stance would assuredly mean the economy could never sustain full employment – we have thirty years of evidence of that.

And as a matter of terminology, we usually think of a ‘fiscal stimulus’ as a temporary injection of net public spending to meet a sudden fall in non-government spending growth, that opens up the ‘spending gap’ I mentioned before.

The ‘stimulus’ is designed to redress that gap and stop unemployment from rising.

We would not think of a steady-state (continuous) fiscal deficit at a level that maintain full employment given the underlying steady-state non-government spending levels as a ‘stimulus’.

Gittins doesn’t understand that difference when he writes “further fiscal stimulus from a continuing budget deficit”.

We certainly do not want an expanding fiscal deficit when the combination of public and non-government spending is sufficient to maintain full employment.

But that is quite a different matter to claiming that any fiscal deficit is undesirable at full employment, which is what Gittins wants his readers to believe.

I discussed these issues in the introductory suite of blog posts:

1. Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 (February 21, 2009).

2. Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 (February 23, 2009)

3. Deficit spending 101 – Part 3 (March 2, 2009).

If that wasn’t bad enough …

The day before (May 23, 2021), the Sydney Morning Herald published this article – True cost of pandemic and policy failure to leave finances in the red – which also perpetuates the fictions that have dominated the macroeconomics commentary over the last three or so decades.

The article by journalist Shane Wright contains many of the frames that underpin these fictions:

1. “pandemic’s devastation of the nation’s finances” – implying that the government fiscal position can be ‘bad’ or ‘devastated’ if deficits rise.

2. “huge levels of debt over the next 40 years” – implying rising public debt is bad.

3. “a wake-up call for both sides of politics” – implying that politicians are living in a delusory state and will have to get real soon.

4. “gross debt hitting a record $1.2 trillion” – use of the term ‘record’ implies bad, when it is meaningless in the context.

5. “how the government would pay for the debt and deficit run up dealing with the pandemic” – they have already paid for the deficit, when they instructed the RBA to type numbers into bank accounts to facilitate the extra spending.

Further, the RBA has also bought a significant proportion of the increase in public debt via its quantitative easing program. Not mentioned by the journalist.

6. After noting claims by the Prime Minister that “a strong economy” would “pay for” the deficits, the journalist says “This month’s budget shows deficits every year for the next decade and a slowdown in economic growth from 2022-23.”

Implying that the deficits would not be paid for. Revert back to Point 5.

And if there is a slowdown in economic growth from 2022-23, then it means that, given projected non-government spending, the fiscal position at that point is not expansionary enough.

7. Some mainstream economist is then quoted as saying “how much damage had been done to the budget” would be revealed in an upcoming report.

His view is to be disregarded.

A fiscal position is not something that can be “damaged”. This sort of framing and language is totally inapplicable.

What has happened is that non-government spending has fallen, unemployment rose and to reduce that ‘damage’ (to real things that matter like jobs), the fiscal deficit rose.

That is not damage to the government policy position. It has not meaning to use terms like that.

The government response was to reduce real “damage”.

8. Further poor framing and language from this mainstream economist – “how much trouble the budget is in”.

A fiscal position cannot get into “trouble” like a naughty little boy or girl. Such language implies a rising deficit is bad and a falling deficit is good.

Revert back to my earlier discussion as to why that terminology and construction is a reflection of just plain ignorance.

9. Another mainstream economist is quoted (who I can tell you from personal discussions is not on top of these matters) is talked about “the whole budget to implode”.

Implode?

Apparently, we need to restore “fiscal discipline” – again using morality terminology.

10. The article quotes the Treasury secretary who last week claim that at some future point, the government would have to:

… accelerate the rebuilding of our fiscal buffers.

This is the myth that a fiscal surplus provides the government with more capacity to meet a crisis than if the nation goes into a crisis with a fiscal deficit.

It is a plain lie.

The currency-issuing government can always expand its deficit to meet a sudden shortfall in non-government spending (relative to the level necessary to maintain full employment), irrespective of its current fiscal position.

Those who think otherwise, claim that if the public debt is too high, the bond markets will not fund the increase in deficits at reasonable bond yields.

Of course, this implies the bond markets dominate the government.

That is another myth.

The last 20 years in Japan, the period since the GFC in many other nations, and the pandemic in all countries, has shown pretty clearly that the central bank calls all the shots in this regard.

There can never be a situation where the bond markets can render a currency-issuing government insolvent or force up bond yields, if the government chooses otherwise.

Further, the idea that a fiscal surplus represents savings that can be used to expand future spending possibilities, which the “fiscal buffers” terminology implies, is false.

Governments do not ‘save’ when they run surpluses.

They actually destroy non-government saving.

Saving is the act of a financially-constrained spending agent (household, firm, etc) who retain a proportion of their current available income in order to expand their future spending capacity (via the interest on the financial assets created by the ‘non-spending’ now).

Such a constraint is not binding on the Australian government and so its future spending possibilities are only limited by what is for sale in the Australian dollar, irrespective of what is has been doing in the past.

Conclusion

These narratives that are increasingly appearing in our public commentaries are dangerous and emphasise that there has not been a fundamental shift in the macroeconomic discussion as a result of the pandemic.

The policy practice has been relaxed given the scale of the health disaster and the evidence is clear that these narratives have always been false.

But those who have the ‘platform’ – the journalists, the economists that get most of the airspace on TV and radio etc – are stuck in the mainstream paradigm and don’t appear to have learned much at all from the evidence.