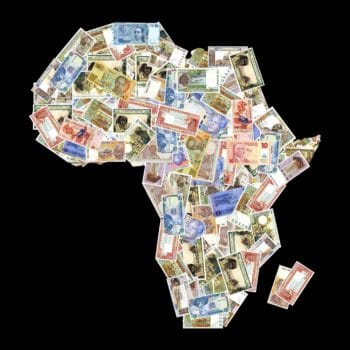

Money on the left: confronting monetary imperialism in Francophone Africa

Ndongo Samba Sylla interviewed by Scott Ferguson, Max Seijo & William Saas

Below is a transcription of the March 14th episode of the podcast Money on the Left.

(Hemen daude ekonomia eta politika gurutzaturik. Marx at his best! Zeinek gidatzen du ekonomiak ala politikak? Noski, dialektikarik ez da inon exisititu, ezta inoiz ere)

Ingeles errazean, sorry.

Zipriztinak:

Saas: (…) Sylla is also the author of many articles and three books, including the recently published L’arme invisible de la Françafrique, or ‘The Invisible Weapon of Franco-African Imperialism’. In that book, Sylla and co-author Fanny Pigeaud lay out a comprehensive case against the CFA Franc, which is the neo-colonial currency union that presently constrains the social, political, and economic prospects of each of its member states. In this episode, Scott and Max talk with Sylla about the history of political economy in pre- and post-colonial Africa, the theoretical bases and political stakes of the anti-CFA Franc movement, and how Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) ought to inform current and future efforts to restore political and economic sovereignty to West African nations. Special thanks to Ndongo for taking the time to speak with us, and to Alex Williams for producing this episode.

(…)

Ferguson: So your recent work, and your recent co-authored book, focuses primarily, as you said, on the present history of the neo-colonial monetary system that is the CFA Franc, in Francophone Africa. And really, in this conversation, I want us to dive into that. (…)

Sylla: (…) So I think, as progressives, it’s important to open the money ‘black box’, and make it understandable for ordinary people. And that’s why I also appreciate very much the efforts made by the Modern Monetary Theory movement.

(…)

Seijo: So I was wondering, if we can take those ideas – money is inherently political, and that in the production context it’s present in the first and last instance – and I was wondering if we could apply it to the pre-colonial northern and western African societies. And I was wondering if you had any insights into the credit and debt relations that perhaps preceded European invasion and colonization.

Sylla: (…)

(The Quest for Economic and Monetary Sovereignty in 21st Century Africa: Lessons to be learnt and ways forward. November 7-9, 2019, Tunis.)

Ferguson: (…) what changes under colonial rule? …. Do you see colonization, and changing money relations, as a purely top-down process, or do we see instances where local political, legal, customs, play a large role also in shaping colonial relations?

Sylla: Yeah. I would say that colonialism has transformed deeply the monetary experience of African people. First we have to remind that colonialism was first associated with … violence. And you could see that with the example of the conquest of Algeria. Because it happened in the 1830’s, and it was … the beginning … of the military colonization of the continent. What happened there was … looting, and the French troops, for example, looted the stock of gold, the stock of silver, of Algeria, and this was shared by the looters, by the French Treasury, and by King Louis-Philippe himself. And this was important because just after the conquest of Algeria, in 1848, there was the abolition of slavery in France. And this was something really important from a monetary point of view, because the slave owners, French slave owners, had to be compensated. … Part of the compensation was used to set up colonial banks under the supervision of the Bank of France.

This is, for example, the case for the Bank of Senegal, which was created in 1853, and which had its headquarters in a town named Saint Louis in the north of Senegal. And this Bank of Senegal is the ancestor of the current Central Bank of West African States. So you could see through this telling example the relationship between debt, credit, money, and … the setting up of the banking system. I [remind] this story because the creation of this Bank of Senegal was illustrative of the objectives of the … colonial project and also the place of money in the colonial project. Because the colonizers used money for extractive purposes–that means to bring the colonies to produce the resources and products demanded by the metropolis, and also to drain economic surpluses to the metropolis.

At that time, there was something called the “Colonial Pact.” … The Colonial Pact is not really a pact, … [a] convention between partners. It was a way of designing … the operating principles of the colonial economy. And those operating principles were, for example, the fact that the colonies were legally prohibited to industrialize–they had just to supply raw materials to the metropolis, which would transform them into finished products, and then sell them back. The metropolis had also the monopoly on exports and imports from the colonies. It also had a monopoly on the transportation of the products of French trade of the colonies. And in this colonial economic system, the role of money was to allow this extraction of value. That’s why, when banking credit was created for production, it was limited just to the production of cash crops and raw materials demanded by the metropolis. And when credit for consumption was created, it was just to create a demand for the goods imported from the metropolis.

[W]hat is sad is this colonial function of money is still in full force in countries using the CFA Franc. So the first impact of … the introduction of colonial currencies has been to kill the monetary pluralism that was a characteristic of African polities. Because you could see, in the same town, different currencies. But when the European powers came, they wanted to lower transaction costs. That’s why they created currency blocs. But those currency blocs were not what we would call now ‘Optimal Currency Areas’; … they were created just for colonial purposes. And by doing that, the colonial powers have disrupted African economic structures, and they have made them dependent on external economic diktats. That means they are no longer sufficient, … economically speaking.

Ferguson: So, to follow up on that, you were discussing the ways in which you’re very critical of the commodity theory of money, which we sort of associate with the classical political economy of Locke and Smith, and it transforms, and takes on new forms, in the marginalist revolution, and the turn to what we call neoclassical economics. Where does that intellectual history link up with the story of European invasion, colonization, and violence?

Sylla: I think that neoclassical economics does not talk in a satisfactory way about the origins of money, and how money was created, for example, by … countries or regions which have been colonized by Europe. They will just say that money was created because it is more efficient than barter. And European powers, of course, knew that money does not work like that. That’s why what they did first [was] imposed their own currency. In our book, we have quoted Hyman Minsky, who used to say ‘everyone can create money; the problem is to get it accepted’. And for me, this is really interesting when we think about the story of the imposition of colonial currencies.

If we take the case of the cowries, for example. When France conquered West Africa, and created the Federation of West Africa, the first thing they did is to stop the imports of cowries, because the cowries came from the Indian Ocean. And so they stopped that, and sometimes they went to markets with military people, just to impose traders to use the French currency. And they have put legal sanctions for people not accepting French currency. But we also see the importance of … the fiscal instrument, to generate a demand for money. Because through the obligation that indigenous people have to pay taxes, they created a demand for the colonial currencies, because people had to work in sectors where they would receive the cash, so they would be able to pay their taxes. And this is something which, let’s say, this process, this way of ‘money-to-work’, you could not see that in neoclassical economics, but you could see that, clearly, for example, in Modern Monetary Theory. That is, the issuer of the currency has to spend, first, before … the people who have to pay taxes pay their taxes. This is something you could see in the history of the colonial currencies, but this kind of story, you will never find that explained in neoclassical economics.

Ferguson: So, I know this is a sweeping generalization, but would it be fair to say in terms of the conscious intentions and actions of the French in the 19th century, that they were commodity theorists at home, and chartalists abroad when they needed to be?

Sylla: Yeah, I would agree with that. They clearly acted in the chartalist way. And yeah, they knew that if they wanted to substitute the French currency, and abolish the indigenous currencies, they had to impose taxes. … Through that, they were able to create a demand for the French currency. Because African people had resisted … five decades before they came to really accept the French currency. And this had been possible through the fact of saying if you do not pay taxes, you will face legal sanctions, and yeah you have to pay taxes. And when you have to pay taxes, you have to earn money, and you could earn money only by producing what is demanded by the metropolis. And that’s how they manage to impose their currency.

Ferguson: Thank you.

Seijo: So I wanted to bring this back to some of your more recent work, specifically on the CFA Franc. And I was wondering if, for our listeners, you could define what the CFA Franc is, and then, perhaps, narrate how it shaped the post-colonial political economies of Francophone Africa in the early years of decolonization.

Sylla: Yeah. The CFA Franc is … a currency born during the colonial period. Now it is the acronym for two different currencies. The first is the Franc of the African Financial Community, this is the currency of eight countries, members of the West African Economic and Monetary Union. And there is another CFA Franc, it’s the Franc of the Financial Corporation of Central Africa, for the six countries belonging to the Central African Economic and Monetary Community. So we have two CFA Francs, but at the beginning there was just one CFA Franc. And the beginning was in 1945, that is just after the Second World War. And at that time, the acronym meant ‘Franc of the French Colonies in Africa’. So it was clear that this was a colonial currency, which was circulating in sub-Saharan colonies of France. The currency was created, officially, on December 26, 1945, by the General de Gaulle and his Finance Minister.

30 Minute Mark

Sylla: [It was clear that this was a colonial currency] which was circulating in the sub-Saharan colonies of France. The currency was created officially on December 26, 1945, by General de Gaulle and his finance minister. And the currency was created the same day that France ratified the Bretton Woods agreement; the same day also that the new parity of the French franc was declared to the IMF (which was just born).

The CFA Franc was created in a context where the French economy had been destroyed during the war, and there was not enough foreign exchange reserves. There was high inflation, many shortages, et cetera. And so, the decision at that time was whether we should have a devaluation of the French franc, which would be homogenous throughout the empire. Because at that time, there was just one currency circulating in more or less the whole empire, except, for example, in India and Indochina. It was the French franc which was circulating in the empire, and of course the bank notes were more or less differentiated from one place to another. But it was basically the French franc. And as the French economy was in a more precarious state, the technicians of the ministry of finance in France said “it would be better that we devalue the French franc.” And that decision implied that the new currencies be created. And the CFA franc was created in that context.

That means it has been created with a devaluation of the French franc. And the devaluation of the French franc has abolished what was called “monetary unity”—that is, one currency circulating in the whole empire. So, the CFA Franc is … a devalued French franc. But what is interesting is that when the CFA Franc was created, it had an external value higher than the French franc, because one CFA Franc was exchanged with 1.70 French franc. And in 1984, there was a devaluation of the French franc, which was not followed in the colonies. And as a result of that, one CFA Franc was worth 2 French francs. That means that the CFA Franc was born overvalued, because in the British colonies, their currencies had parity, which was obviously weaker than the British pound. But France decided to keep the CFA Franc at an exaggerated external value, because it was in interest for France to break up the ties that the African colonies had nurtured during the war with the other parts of the world—for example, Latin America and Asia.

During the war, the trade between France and its colonies had decreased a lot, and France wanted to regain control of that trade. And so, it was interesting for France to have colonies with overvalued currencies. As a result of this overvaluation, the colonies could no longer sell competitive products in Asia and Latin America, so they were obliged to sell it to France. And at the same time as their currency was overvalued, they could buy, cheaply, goods from France. So it was very profitable for France to have colonies with overvalued exchange rates. What was also profitable for France is that the French franc was, at that time, a very weak currency. And the Bretton Woods regime was a regime with U.S. dollar hegemony. And goods had to be bought in U.S. dollars. But with the CFA Franc, France could buy all the raw materials, all the products, in its colonies without using U.S. dollars, because France could just credit the amount of exports of the colonies in the French franc. And that’s what France did. This was really important for France, as it contributed to strengthen, a little bit, the French franc exchange rate. Because if France had to earn dollars to buy its imports in Africa, it could have been very disruptive for the French economy, which was really in a mess just after the second World War. The creation of the CFA Franc was also a means for France to have total control on its colonies, because all the decisions—economic, financial, and political—were taken from France.

Seijo: So you’ve just explained the historical creation of the CFA Franc, and how it shaped African political economics. Could you talk about what the current status of the CFA Franc is, and how it’s related to the Euro currency zone?

Sylla: Before answering that question, I’ll give some context about why the CFA Franc still exists. Because after the creation of the CFA Franc, there was some political concessions from France, which allowed the colonies more autonomy and which recognized some rights—labor rights, etc. This process has led to decolonization. But what is particular in the case of France is that other monetary blocks—because in Africa you had many monetary blocks: you had the sterling area; you had the peseta zone; you had the Belgian monetary zone; the dollar zone —and all those monetary blocks were dismantled after formal decolonization.

But this did not happen with France. Because when France knew that the decolonization was something inevitable, France said to African leaders—because most of the Francophone leaders were trained in France; sometimes they even had seats in the French parliament; and those elites would afterwards rule the newly independent African countries. And France told those leaders: I will grant you independence, provided you sign what was called “cooperation agreements”—that means agreements giving France monopoly rights in many areas, for example: raw materials, currency diplomacy, armed forces, higher education, civil aviation. In all those domains, there were cooperation agreements. And this was something very clear: the prime minister of France at that time wrote to the Prime minister of Gabon at that time, telling him that we will grant you independence but you have to sign those agreements. Without the signing of those agreements, no independence. And it was clearly written. As a matter of fact, all those countries would more or less stay in the safer zone. You could see even in the case of a country like Gabon the cooperation agreements were signed the day of its official independence. So that means that in Francophone Africa, there was not really a full decolonization, but only a partial decolonization. So this is the context which explains why the CFA Franc survived the wave of formal independences in Africa.

Ferguson: (…) doesn’t really open up a question of how money is really the central question and problem when it comes to the process of decolonialization. Is that your sense? Do you have a sense that putting money at the center of the story brings new light to this history?

Sylla: Yeah, and I must say that I have learned a lot, and [began] seeing things differently, when I started to work on the CFA Franc. I had the more or less conventional view about the process of decolonization, but when you factor in the money aspect, you see why you could not really talk of real decolonization without taking into account whether the money management was decolonized or not. And clearly, in the case of the CFA Franc, one of the most important aspects for France was to have the CFA Franc zone maintained. And you could see many statements from ministers, from MPs, saying that it’s important that African countries remain in the CFA zone. Because if they remain in the CFA zone, it is as if those African countries were an administrative department of France. Because as France could buy all African products, just by credit—so it is a very critical thing for them, very critical, because they could buy everything just by crediting it in their own currency in the operations account. And that means that what is called the exorbitant privilege for the U.S. dollar is somehow what France enjoys in its former colonies through the maintaining of the CFA Franc. Because France has an exorbitant privilege. But now this has declined with the arrival of the Euro. But nonetheless, it has been a very important exorbitant privilege. And I think that, without this arrangement, it would have been really tough for France to rebuild its economy and also be a major economic power.

Seijo: So can you talk a little bit about how the CFA Franc is operating in the Euro context?

Sylla: In fact, the CFA Franc mechanisms have not changed since colonial times. They are really simple; they are based on four principles. The first principle is the fixed parity against the French currency. Which was the French franc before, and now the Euro. That means the peg is always there, it’s the same peg and it normally should not be devalued. The second principle is the freedom to transfer capital and incomes within the Franc zone. The Franc zone gathers the 14 countries using the CFA Franc, and also the Comoros and France. The Comoros have a so-called national currency, but it functions in the same way as the CFA Franc. It’s just the parity that is different; otherwise it’s more or less the same working principles. The third principle

45 Minute Mark

Sylla: The third principle is that the French Treasury promises to guarantee the convertibility of the CFA Franc into French currency. And this convertibility guarantee means that the French Treasury promises to lend foreign reserves, Euros, to the two central banks–the one in West Africa, the other in Central Africa–if they no longer have any foreign exchange reserves. That is the promise of lending money. It is as if the French Treasury was acting like a private IMF for the African Central Banks. [A] private IMF to say that if they have … [a] shortage in foreign reserves, [the] French will be there to lend them money so that the fixed peg is maintained, so that the free transfer of capital in incomes will not be impeded. What has to be said is that France has seldom performed that role of lending money in times of crisis.

The fourth principle is that, as a result of this convertibility guarantee by the French Treasury, the central banks, the central banks are required to deposit in a special account of the French Treasury fifty percent of their foreign exchange reserves. After independence, this was one hundred percent. This has been lowered to sixty five percent in 1973. And since 2005, it’s fifty percent. So, those foreign exchange reserves are deposited at the French Treasury as a counterpart to the guarantee of convertibility. And this is something you would never see anywhere else than the CFA Franc. All of these mechanisms date back to the colonial period. And they are still functioning like they functioned in the colonial period. The French authorities are represented in the bodies of both … central banks and they have veto power. That means that no monetary policy decisions, including the decision to devalue the CFA Franc, can be taken without the approval of the French government.

People don’t know also that the CFA Franc is a currency unknown in international markets. Every time a CFA Franc is exchanged against the Euro this has to pass through the French Treasury. That means that the French Treasury is de facto the foreign exchange office of African countries because the CFA Franc is unknown in international markets. Everytime there is a conversion it is through the French Treasury. I have to add that the bank notes, the coins are still produced in France without any international call for tenders. And the stock of gold of the central bank of West African states is at 90% held by the Bank of France.

All these elements show that the CFA is a colonial monetary arrangement. It’s workings have not changed with formal decolonization. It is interesting to say that [in] the first report about the Franc Zone published in 1953, it was clearly indicated that the CFA Franc is technically similar to the French franc. In fact, the CFA Franc is a sub-multiple of the French franc because there is a total integration between the monetary space in the franc zone countries and the monetary space of France. So, it’s the same money. The sole difference is that, for the CFA Franc countries, you have different bank notes; but it’s more or less the same.

Now with the era of the Euro, you could say that the CFA Franc is the sub-multiple of the Euro. What has really changed with the arrival of the Euro is that the governance of the CFA Franc now includes the European Union authorities [Council of the EU, European Central Bank, Economic and Financial Committee]. Because when the French knew that the French franc would disappear and [cede] it’s place to the Euro, they negotiated with their European Union … partners and they [said] they want to peg the CFA Franc with the Euro. They had to negotiate that with their partners because there were some critical voices, for example Germany and Austria, which [said] that, normally, if France want[s] to peg the currency of its former colonies, it’s the European Union who will be sovereign. There will be no place for France to [have a] say. What happened is that France was efficient enough to convince the European Union authorities [of] the fact that guaranteeing the convertibility of the CFA Franc is not a danger to [the] French public budget and so to European Union stability. They made a compromise on that basis.

The compromise was that now France [had] to have the consent of European Union authorities if the membership of the CFA Zone is to be enlarged. Also, exchanges have to be brought to the French convertibility guarantee. In the same way, France should give the European Union authorities prior information in the case that the CFA Franc parity is planned to be modified. For example, if a devaluation is planned France has to inform first the European Union authorities. These dynamics mean that now the CFA Franc is under the tutelage of both France and the European Union authorities. So, this is a change brought by the arrival of the Euro.

The second change …. has, let’s say, an economic nature. By pegging the CFA Franc to the Euro, now the African countries and their central banks are more or less submitted to the same restrictive rules in terms of inflation, public debt and public deficit[s]. The mandate of our central banks is to have price stability and they target a rate of inflation below three percent. This kind of setting tends to lead to deflationary outcomes, which are bad for the long-term growth of African countries. The other thing is that African countries receive their export income in dollars, whereas their currency is pegged to the Euro, which has often appreciated a lot vis-a-vis the dollar. For example, between 2002 and 2008, the Euro has appreciated a lot vis-a-vis the dollar–more than ninety percent cumulatively. At that time, many agricultural producers were bankrupted because of just one factor: the Euro was so strong. So, the arrival of the Euro means less export competitiveness for African countries. This is a serious handicap for structural transformation and also the capacity to record trade surpluses.

Ferguson: In the way that you tell the story of the rise and evolution of what is essentially a colonial project, the CFA Franc, it seem that it begins with a clear, somewhat clear, chartalist intention and consciousness. But by the time we get to the later twentieth century and the Eurozone, it seems like the chartalist insights, as evil as they were put to use, are really lost. And my sense is that this happens in the way that both the Eurozone and, of course, the CFA Franc really provide little place for fiscal capacity in any of the European economies or the Francophone African economies. Is that fair to say?

Sylla: Yes, that’s true. Because we are no longer in the same type of international mindset. From 1945 to 1980 more or less, there was the idea that economic development should be encouraged using heterodox policies. And so there was an active role for central banks and an active role for states. But since then the mindset has changed. Now, monetary policies are too orthodox, at least for developing countries like those of the CFA zone. The budgetary policy, fiscal policies are too orthodox. African countries are trying to follow the dictates of France, the IMF, and also the European Union. You don’t have to have budget deficits. You don’t have to borrow money passed some given level, etc. And so, it has become difficult for many countries. At that time, as you say, there was this chartalist perspective by France on African countries. But with the integration of France in the European Union this chartalist perspective has disappeared. Because now France had no longer the same margins to create money to, let’s say, buy African products. France is no longer sovereign monetarily and you could see that with the relationships with the African countries, which are blindly following the crazy Eurozone model.

Ferguson: We’ve been talking at a theoretical level for a while and I was wondering if you could give our listeners a real contemporary example of the disaster that the CFA Franc for people in communities, whether it’s in Senegal or elsewhere.

60 Minute Mark

Sylla: You just take a look at the long term growth rates. For example, if you take the real GDP per capita of the most important economies in the Franc zone, you’ll see that today it is lower than 40 years ago. Take the case Côte d’Ivoire. In 2016, its real GDP per capita was 1/3 lower than it was in 1978, which was its best year. The annual growth rate of real GDP per capita for Côte d’Ivoire, between 1960 and 2016, is more or less 0.5%. In my own country, Senegal, during the same period, annual rate of growth for real GDP per capita is 0.02%. That means there has been no long term growth at all.

Nowadays, you will hear people say that the CFA Franc countries today have a high rate of economic growth. And that’s true; since 2012 there has been a 6% rate of economic growth. But this is a kind of economic growth which is catching up with the past best levels of economic performance. Out of the whole 14 CFA Franc countries, 9 of them are ranked as less developed countries, and four of the remaining five have a real GDP per capita lower than they had in the 1970s and 1980s.

What’s also interesting is that you could not explain why this CFA zone still exists. Because you’ll see that trade between African countries and the Franc zone is very limited. In Central Africa, it’s less than 5%. After 70 years of so-called monetary integration, they have just much less than 5% of original trade. If you take the case of West Africa, it’s better but nonetheless not very important. Between 10-15%. If you take also the level of competitiveness of African countries of the Franc zone they fare the worst in the world. In w Africa, except Côte d’Ivoire all the remaining countries and chronically in a state of trade deficit. Countries like Benin, Niger, Mali, Burkina Faso, they never recorded one year of trade surplus. They are structurally in a situation where they have to be indebted in foreign currencies. They will never be able to develop because the mechanism of the CFA Franc will never allow them to be developed. On the one hand, as I said earlier if you want to produce you have to create money, but in the CFA Franc Zone the central banks are more or less forbidden to facilitate money creation. The reasoning of the French authorities for this is very simple. They say that more bank credits means more imports. More imports mean less exchanged reserves. And less exchanged reserves imply more pressure to defend the fixed peg to the euro. So at a macroeconomic level there is this rationing of credit. And there are some crazy indicators that show that the CFA Franc exchange rate is more or less functioning like a currency board. That means that the monetary base of CBs is covered nearly at 100% by foreign reserves. In this context there is not enough credit to stimulate production. And those who happen to produce in order to sell abroad cannot be competitive because the currency is too strong because it is pegged to the Euro.

So on the one hand, there is no credit for production. And when you are able to produce you cannot sell abroad because you have a strong currency. Because you have no monetary sovereignty. So this is the case of the CFA Franc zone and that’s why there is no economic dynamism at all. Economic growth in the CFA Franc zone is never triggered by internal dynamics, but just by external dynamics. For example, good terms of trade and cheaper interest rates, … on international financial markets. So this is the sad story of the CFA Franc. Somehow owing to these mechanisms when there are economic crises it’s much more difficult for CFA Franc countries than others because the exchange rate cannot be used as a policy variable. As they follow the neoliberal rules, so public deficits are not really encouraged and the central banks generally in those circumstances follow an orthodox monetary policy, and that means that whenever there are economic crises, the main way of adjusting economically is what is called internal devaluation. That means lowering internal prices and limiting public deficits and letting the private sector enterprises go bankrupt. That is the main mechanism of adjustment in the CFA Franc.

Siejo: So, given those harms, how has the CFA Franc been challenged by African people and governments, in the past and now?

Sylla: There have been many attempts to challenge the CFA Franc, at least there have been four periods. The first took place just after the independences. Guinea was the first [Sub Saharan African] country to challenge the CFA Franc. Guinea took their independence in 1958. Two years after, they had their own national currency and left the CFA Franc. But France did not accept that, and in retaliation the French secret services flooded the Guinean economy with counterfeit bank notes. Through a large scale military operation called Operation Persil. This operation is described in books and especially by the people who performed it. And obviously those counterfeit banknotes disrupted the Guinean economy, and this was a warning from France saying that if you want to get rid of the CFA Franc reflect twice because we will sabotage your economy.

Another example is Togo in the early 60s. They had a political leader named Sylvanus Olympio, who had been trained at the London School of Economics. He wanted a national currency and to diversify Togo’s international relationships, namely with American, German, etc. But he had never been able to create his national currency because he was killed days before its launch, in front of the American embassy in 1963. Togo and Guinea were the first two countries to challenge France, but more or less they have failed. Togo has failed and Guinea has exited, but its economy never recovered.

There were also attempts to challenge France in the mid 1970s. In that period, there was some turmoil following the suspension of the Dollar-gold convertibility. Africans were angry to see that France had devalued its currency without warning them. This devaluation of the French Franc was followed as a result of the fixed peg by the African countries using the CFA Franc. This has increased inflation, the debt burden, and also had reduced the value of their foreign exchange reserves. Because at that time, all the foreign exchange reserves were held at 100% in French Franc, so Africans were not happy about that. France responded with some minor concessions. Since then, France allowed African countries to reduce their monetary deposit rate to 65% and accepted that the CBs now be managed by African staff. Until the mid 70s, the CBs managers were in Paris. But as I said earlier, France is still represented and has a veto power.

There was a third wave of challenges in 1994, when the CFA Franc was devalued for the first time in its history. This was a shock for many African leaders who opposed the devaluation, but it was nevertheless enforced by France and the IMF. When France decided that there would be a devaluation, this produced inflation, impoverished urban dwellers and led to riots in which many people were killed in the days that followed. Those protests were not against the CFA Franc in particular, but were an immediate response to the devaluation.

And now there is this current wave of protest that started in 2015/2016, and what’s interesting about this wave is it’s more popular and more Pan Africanist. For the first time, everyone is talking about the CFA Franc. Recently, Italian government officials accused France of behaving like a colonial power in Africa, and this of course brought more visibility to the CFA Franc.

There is an episode which is not really known, but which is interesting as it illustrates how France dominates this system…

75 Minute Mark

Sylla: Now the issue of the CFA Franc is gaining more visibility and recent declarations of Italian government officials accusing the French of behaving like a colonial power in Africa have also given more visibility to the CFA Franc.

There is an episode which is not really known, but which is also really interesting as it illustrates how France dominates this system. In 2011, there was a presidential election in Côte d’Ivoire. There was some tension between Laurent Gbagbo, who was the incumbent President and Alassane Ouattara, who was a former IMF staff and also a protege of France. There was an electoral dispute and France [took] sides with Ouattara. To put pressure on the Gbagbo government, the French government asked the BCEAO, the central bank of West African states, to stop supplying the Ivorian economy with bank notes, and to stop dealing with the Gbagbo regime, which could no longer access its accounts at the central bank. The French government also asked the French banks’ in Côte d’Ivoire to cease all external operations, and finally, the French government blocked the operations account. The operations account is the account where all operations to convert the CFA Franc into Euros, and vice versa, pass.

As a result, there was a financial embargo against Côte d’Ivoire and against the Gbagbo regime. The Gbagbo regime [then] chose to create a new national currency and were [having] discussions with some countries [about helping] them manage their foreign exchange reserves. But they didn’t have time to create this new currency, as France bombed Gbagbo’s palace to install Ouattara. This was one intervention among more than forty-some done by France since the independencies in Africa.

So, there have been many attempts to challenge the CFA Franc, but each time France has been very strong and sent very clear messages that France will never allow African countries to exit the CFA Franc. But I think now with the current wave [of dissent], it will be much more difficult for France to have that stance.

Ferguson: From what I’ve read, there seem to be two resistance strategies right now to the CFA Franc, and ways of exiting it and potentially breaking it up. Could you quickly outline those two strategies and discuss what you believe their strengths and weaknesses are?

Sylla: Yeah. In fact, we could exit the CFA Franc on a national basis. That means Senegal would say, “I want my own national currency,” and so I’m exiting the CFA Franc. This is the path followed by Guinea, Mauritania, Madagascar, etc. And legally speaking, it [would be] very easy. The Senegalese government would just have to notify the West African monetary union of this decision, and in six months they could have their own national currency. But it’s difficult because if you go alone, you don’t know what consequences you could face from France. This is what I call the nationalist exit, but there is another type of exit, what I call the Pan-African exit. That means, instead of African countries trying to initially have their own currency, they say, “we no longer need France.” France could [then leave] the CFA Franc system.

This option is made plausible by the fact that the so called guarantee of convertibility by France doesn’t exist because this guarantee of convertibility, as I said, is a promise to lend money in Euros when the central banks are devoid of any foreign exchange reserves, and this generally doesn’t happen. It [only] happened in the 80s because it was a very difficult period marked by the international debt crisis, and even in that time the amounts lent by France were really ridiculous. Since African countries [were] independent in the 1960s, the French convertibility has been used for about a decade. That means that African countries don’t need France, and they could tell France that they don’t need its “convertibility guarantee”. That is possible, but the Pan-Africanist and the nationalist exit are just formal ways of exiting the system. The important questions are, “what are you going to do? How could we achieve monetary sovereignty?” In this regard, there have been many proposals.

Seijo: What do you see as the path forward for African nations looking to exit the CFA Franc?

Sylla: With regard to the issue of how to get out of the monetary statu quo, there are in my opinion, four different points of view. First, there is the perspective I call symbolic reformism, which consists [of] touching only the visible systems of monetary coloniality without touching the fundamentals of the CFA Franc system. This includes proposals such as changing the name of the CFA Franc, having banknotes and coins manufactured outside of France, and even further reducing the deposit rate of foreign exchange reserves at the French treasury. Emmanuel Macron, for example, made this type of proposal, and he even suggested that he was open to expanding the CFA Franc zone to a country like Ghana.

There is the second perspective that I call adaptive reformism. These are reforms that aim to adapt the CFA zone to the current context, marked by the economic and geopolitical decline of France and the Euro, but with the ultimate objective of maintaining it. This is the case, for example, of those who want the parity of the CFA Franc to be more flexible because the peg to the Euro is too rigid and undermines the price competitiveness of African exports, and because the CFA zone is increasingly trading with China and other countries [using] the US dollar.

For many economists of different sides, there is this proposal of [basing] the exchange rate of the CFA zone on a basket of currencies, but the problem with this perspective is that it is simply unrealistic because it ignores the functioning of the CFA zone. Exchange rate flexibility is not an option in the CFA system because the convertibility guarantee is offered at a fixed exchange rate and in the currency of the guaranteeing authority. Many people who claim to be experts and moderate [still don’t] understand that the demand for flexibility is incompatible with the maintenance of French guardianship; it is one or the other.

Thirdly, there is the perspective I call neoliberal abolitionism that is an exit from the CFA Franc that follows the neoliberal monetary integration model. By that, I am referring to the Eurozone model. I have in mind those countries in West Africa who want to be part of the single currency project of the ECOWAS (Economic Community of West African States). This single currency project for West Africa normally should be launched next year, but I don’t this [think] this will be done, owing to technical and political problems. Technically, no country yet fulfills the convergence criteria copied from the Maastricht Treaty and defined as prerequisites for entry into the new monetary zone to be created. Politically, the current Nigerian President, who has just been re-elected, Muhammadu Buhari, has been demanding, since 2017, a divorce plan from the French treasury of the eight West African countries that use the CFA Franc, but [since] then, the countries of the West African monetary union that use the CFA Franc have remained silent, for fear of angering France. It is very unlikely that there will be an ECOWAS single currency by next year.

Even if it were possible, for me it would be a very bad idea, for the simple reason that sharing the same currency is not justified among ECOWAS countries, owing to a number of factors, like for example Nigeria’s disproportionate weight. Nigeria accounts for at least 70% of West African GDP. [As well], there are differences in economic specialization. Nigeria is an oil producer and exporter, whereas, you will find in West Africa at least nine countries which are net oil importers. There is also the fact that economic cycles are not synchronous in West Africa and the level of inter-ECOWAS trade is very low. All of these elements point to the fact that a single currency is premature and not justified economically in West Africa. We have to also say that there is no planned federal fiscal mechanism, but rather, limitations on public debt and deficits, following the Maastricht criteria. That means, in case of economic crisis, countries in this currency union would only have the option of so called internal devaluation [via] the lowering of internal prices, which often comes to austerity policies and the growth of unemployment.

Lastly, there is my extremely minority perspective which I call sovereign abolitionism that is an exit from the CFA Franc that breaks with the neoliberal model of economic integration and that strengthens the sovereignty of individual countries and also the sovereignty of [countries] collectively. If we put aside the political criticism of the CFA Franc, the real economic criticism is that the CFA zone must not exist because it has no economic justification. It is not a so called “optimal monetary zone.” Each country must have its own national currency because economic fundamentals, levels of development and productive dynamisms are not the same. But saying that does not mean that we cannot have systems of solidarity between African countries. For me, this is possible.

That’s why my preferred option is that of solidary national currencies. Concretely, that means that each country has its own national currency with its national central bank. The exchange rate parity is determined according to the fundamentals of each country, and countries have a common payment system. Their currencies are linked by a fixed but adjustable parity to a common unit of account, and also there is solidarity in the management of foreign currency reserves. Finally, there are common policies to ensure energy and food self-sufficiency, because in the ECOWAS zone energy and food products represent between 25-60% of the value of imports, depending on the country.

The advantage of this option for me is that it makes it possible to reconcile macroeconomic flexibility at the national level, that means the possibility to use the exchange rate as an instrument of adjustment, and at the same time to have solidarity [between] African countries. This option also helps break the Anglophone, Francophone, and Lusophone divide, [which] is a legacy of colonialism. What is unfortunate is that this option is unlikely to emerge. Generally, people talk about national currencies in the CFA zone, and many Pan-Africanists are convinced that Pan-Africanism means having a single currency for the largest possible number of African countries. I see this position as not really solid on economic grounds. Unfortunately, those who defend the CFA Franc are not interested by national currencies and those Pan-Africanists that want to get rid of the CFA conceive of the alternative as just the single currency, but not national currencies. That is a little bit unfortunate, but obviously, I will try to push this argument about the necessity to have national currencies organized in a solidary way.

Seijo: Before we conclude, we wanted to give you the opportunity to talk to our listeners, and tell them what they can do to help overturn this unjust monetary order.

Sylla: To finish, I would like to make a call to the MMT community to join us, to support our fight for the abolition of the CFA Franc and also for an international monetary system better suited to the needs of developing countries, the so called global south. In this perspective, if the basics of MMT were made more available in French, and other languages besides English, it would also help.

Seijo: Well, Ndongo, it was a real pleasure having you on Money on the Left.

joseba says:

French Colonialism Is Alive and Kicking in Africa, Has the Continent in an Iron Grip

https://www.checkpointasia.net/french-colonialism-is-alive-and-kicking-in-africa-has-the-continent-in-an-iron-grip/

“CFA franc. These two words probably do not mean much to most readers, but they encapsulate one of the world’s most enduring – and little-known – economic experiments. In the simplest possible terms, the CFA franc is a currency used by 14 countries of Western and Central Africa, all of which are former French colonies. Hence the name ‘franc’, a reference to the currency formerly used in the colonies: the French franc. Indeed, as we will see, the name is more than just a semantic legacy. France still plays a considerable role in the management of this ‘African’ currency. But, to avoid getting ahead of ourselves, let’s start by laying out the basics.

When we talk of the CFA franc, we are in fact talking of two monetary unions: the Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CEMAC), which includes Cameroon, Gabon, Chad, Equatorial Guinea, the Central African Republic and the Republic of the Congo; and the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU), which comprises Benin, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal and Togo.

These two monetary unions use two distinct CFA francs, but which share the same acronym: for the CEMAC franc, CFA stands for ‘Financial Cooperation in Central Africa’, while for the WAEMU franc it stands for ‘African Financial Community’. However, these two CFA francs work in exactly the same manner and are pegged to the euro with the same parity. Together with a 15th state – the Comoros, which uses a different franc (the Comorian franc), but which, again, is subject to the same rules as the other two – they form the so-called ‘franc zone’. Overall, more than 162million people use the two CFA francs (plus the Comorian franc).

For a long time, the CFA has been a non-issue in public debate – even in France or Africa. This, however, is changing. In recent years, it has been at the centre of an increasingly heated debate in the Francophone world, helped, in part, by books like L’arme invisible de la Françafrique: Une histoire du franc CFA (‘The Invisible Army of Franco-African Imperialism: A History of the CFA Franc’), by the French journalist Fanny Pigeaud and the Senegalese economist Ndongo Samba Sylla. As they put it:

‘For a long time, much effort has been put into keeping the topic of the CFA franc and the issues that surround it shielded from the public debate, in France as well as in Africa. Being poorly informed on the topic, citizens lacked the tools to question the system. However, in recent years, the CFA franc has ceased to be a matter debated solely by experts … and is today the subject of articles, events, television shows and conferences on the African continent and in France.’

On one hand, the French government claims that the CFA franc is a factor of economic integration and monetary and financial stability. On the other hand, the opponents of the currency – which include many African economists and intellectuals – argue that the CFA franc represents a form of ‘monetary slavery’, which hinders the development of African economies and keeps them subservient to France.

In order to make sense of this debate – and before we move on to analysing the actual mechanism of the CFA system – we need to start from the origins of this contentious currency.

A history of violence and repression

The CFA franc – which originally meant ‘franc of the French colonies of Africa’ – was created in 1945, when it became the official currency of the French colonies in Africa, which until then had used the French franc. Officially, granting the colonies their ‘own’ currency was a reward for the decisive role they played in the Second World War. In fact, as Pigeaud and Sylla write, ‘far from marking the end of the “colonial pact”, the birth of the CFA franc favoured the restoration of very advantageous commercial relations for France’.

Indeed, despite the rhetoric about granting greater autonomy to the colonies, the CFA franc was essentially a French creature, issued and controlled by the French Ministry of Finance. This meant that France could set the external value of new currency – its exchange rate vis-à-vis the French franc – according to its own needs. Which is exactly what the colonial power proceeded to do, by imposing a highly overvalued exchange rate on the colonies.

The aim was twofold: to make French exports cheaper, thus encouraging the colonies to increase their imports from metropolitan France (that is, France located in Europe, as distinguished from its colonies and protectorates); and to make the colonial exports more expensive on world markets, thus forcing the colonies to turn to the metropolis to get rid of their excess production. France, having been severely weakened by the war, therefore benefited both in terms of exports and imports, allowing it to regain its market share and to secure the supply of much-needed raw materials.

However, the most obvious benefit for France was the fact that the CFA franc allowed it to continue purchasing resources from the colonies ‘for free’, since it effectively issued and controlled the colonies’ currency, just like it did when the colonies used the French franc. In short, Pigeaud and Sylla note, contrary to French colonial propaganda, the aim of the CFA franc remained that of ‘ensuring France’s economic control of the conquered territories and facilitating the drainage of their wealth’ towards the metropolis.

It should be noted, however, that France was no exception in this regard: at the time, it was common practice among colonial powers to impose forms of monetary subservience on their respective colonies. What sets France apart from all the other former colonial powers in Africa – such as Great Britain, Belgium, Spain and Portugal – is the fact France’s monetary empire survived the decolonisation process which began in the 1950s.

So while most African colonies, upon becoming independent, adopted national currencies, France managed to cajole most of its former colonies (except for Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria) into maintaining the CFA franc. It did so by resorting to all the pressure tools at its disposal: diplomacy, corruption, economic destabilisation, even outright violence. ‘To uphold the CFA franc’, Sylla writes, ‘France has never hesitated to jettison heads of state tempted to withdraw from the system. Most were removed from office or killed in favour of more compliant leaders who cling to power come hell or high water.’

The first step was to force the colonies to sign a long list of so-called ‘cooperation agreements’ before granting them their ‘independence’. Under these agreements, the new states were forced to entrust the management of virtually all key sectors of their administration to the French state, including their currency, by pledging to remain within the monetary union of the franc zone. Pierre Villon, a French Communist MP, noted at the time that in the economic, monetary and financial fields, these agreements tended ‘to limit in practice the sovereignty granted [to the former colonies] by the law’.

To understand why the African states accepted such heavy limitations to their newly won sovereignty, one must grasp the extent of their psychological subjection to France – and their fear of ‘wading into open waters’ – stemming from decades of colonial ‘tutelage’. These were, after all, agricultural or extremely underdeveloped economies.

However, it wasn’t long before the first rebellions against the CFA franc started breaking out. From the 1960s to the 1980s, various countries tried to abandon the CFA system, but very few actually succeeded. As Pigeaud and Sylla write, France ‘did everything to discourage those states that intended to leave the CFA. Intimidations, destabilisation campaigns and even assassinations and coups d’état marked this period, testifying to the permanent and unequal power relations on which the relationship between France and its “partners” in Africa was based – and is still based today’.

When Guinea, after its repeated calls for a reform of the CFA system fell on deaf ears, launched its own national currency in 1960, France responded by secretly printing huge quantities of the new currency before pouring them into the country, causing inflation to skyrocket and transforming the country into an economic basket case.

Similarly, when Mali left the franc zone in 1962, France pressured neighbouring nations to limit trade with the country, contributing to a sharp depreciation of the new currency and compelling Mali eventually to re-join the CFA system.

France is also believed to have played a role in the murder of at least two African progressive heads of state that were planning to launch a national currency and take their countries out of the CFA system: Sylvanus Olympio in Togo (in 1963) and Thomas Sankara in Burkina Faso (in 1987).

This long trail of violence and repression helps us understand how France became ‘the only country in the world to have succeeded in the extraordinary feat of circulating its currency, and only its currency, in politically free countries’, as the Cameroonian economist Joseph Tchundjang Pouemi observed in 1980. It also calls into question the claim that the African states adhere ‘voluntarily’ to the CFA system.

The ‘diabolical mechanism’ of the CFA franc

With this necessary premise out of the way, we can now move on to analyse the ‘diabolical mechanism’, in Pigeaud and Sylla’s words, that underlies the CFA franc. Nowadays, Paris claims that the CFA franc has become a fully fledged ‘African currency’ managed by the Africans themselves. In the late 1970s, in a process that took the name of ‘Africanisation’ of the franc zone, the headquarters of the central banks of the two monetary unions – the BEAC (Bank of Central African States), the WAEMU’s currency-issuing authority, and the BCEAO (Central Bank of West African States), the CEMAC’s currency-issuing authority – were transferred to the African continent. Furthermore, the number of French representatives sitting on the boards of the two central banks was cut back.

However, as Pigeaud and Sylla note, apart from these cosmetic changes, the mechanism at the heart of the system ‘has barely changed since the colonial era’. Today it rests on the so-called four fundamental principles of the franc zone, which continue to grant France almost absolute control over the CFA system, even though France no longer possesses the franc. Indeed, upon adopting the euro, France succeeded in ensuring that the management of the CFA system remained within its exclusive remit, with the European Union and the other member states having little or no say in the matter. The result is that ‘the spirit and function of the device on which this colonial creation rests remain the same as when it was created in 1945’.

The four principles in question are the fixed exchange rate (the anchoring of the CFA francs first to the French franc and now to the euro); the free movement of capital between the African countries and France; the free convertibility of the CFA francs into euros but not into other currencies (or even between the two CFA francs), which means that every foreign payment made in CFA francs must first be converted into euros through the Paris exchange markets; and the centralisation of foreign exchange reserves. The benefits that France accrues from the four principles underlying the CFA system are innumerable. ‘More than simply a currency’, Pigeaud and Sylla write, ‘the CFA franc allows France to manage its economic, monetary, financial and political relations with some of its former colonies according to a logic functional to its interests’.

For example, by virtue of its presence within the institutions of the franc zone (France holds a de facto veto on the boards of the two central banks), Paris still has the power to determine the external value (exchange rate) of CFA francs, without even having to inform the African countries in advance (as France did in 1994, when it devalued the CFA francs by 50 per cent, and then again in 1999, when it adopted the euro). Moreover, thanks to the free movement of capital, French companies can ‘privatise’ the profits made in Africa by repatriating them to France rather than investing them locally.

But the real keystone of the CFA system is represented by the centralisation of foreign exchange reserves: this essentially means that the central banks of the franc zone – the BEAC and the BCEAO – must deposit a part of their foreign-exchange reserves in France, in a special account at the French Treasury known as the ‘operating account’. Initially, the BEAC and the BCEAO were required to deposit almost all their foreign reserves; nowadays, they are ‘only’ required to deposit 50 per cent (the BEAC) and 60 per cent (the BCEAO) of their total reserves. These operating accounts are denominated in euros. They are regularly credited and debited based on the international payments of the African countries. The underlying mechanism of the system is relatively simple: if the Ivorian economy exports cocoa to France for a value of €400million, this sum is credited to the operating account of the BCEAO; on the other hand, if the country imports €400million worth of equipment from the euro area, the operating account is debited for the same amount.

Theoretically, this is a quid pro quo for the ‘guarantee’ of convertibility offered by France to the countries of the franc zone. This arrangement stipulates that in the event of a shortage of foreign reserves, the French Treasury is required to grant an advance to the central banks of the franc zone to avoid a devaluation of the CFA francs. But this guarantee exists only on paper. Paris has introduced strict rules (including a series of automatic mechanisms that are triggered in the event of a scarcity of reserves) that make it highly unlikely for a ‘zero foreign exchange’ situation to arise.

Indeed, as Pigeaud and Sylla note, it is not really France that guarantees the convertibility of the francs; rather, it is the reserves of the large exporting countries, such as the Ivory Coast and Cameroon, that compensate for the scarcity of reserves of countries, such as the Central African Republic and Togo, which have fewer resources. Theoretically, the African countries could dispense with the guarantee altogether. This is testified by the fact that the operating account of the central banks of the franc zone have constantly registered a positive balance since the birth of the system (except for a brief period between the late 1980s and early 1990s).

But the real ‘exorbitant privilege’ that France derives from the operating account is that, through it, it can continue to pay its imports from the franc zone – which include a wide range of agricultural, forest, mining and energy resources, including uranium, of crucial importance for the French economy – in its own currency (first the franc, now the euro), without having to go through other currencies, and thus without depleting its own foreign reserves. To give an example, if France imports, say, $1million worth of cotton from Burkina Faso, it merely has to credit the equivalent in euros to the BCEAO’s operating account.

A barrier to development

And what about the alleged benefits that the CFA system brings to the African states? According to its defenders, the CFA franc has promoted the economic development of the member states, facilitating the region’s economic integration and creating an environment of macroeconomic stability. In reality, Pigeaud and Sylla argue, the CFA system inflicts ‘four important handicaps’ on the member countries.

The first two handicaps are obviously the fixed exchange rate and the anchoring of CFA francs to the euro. As is well known, a country that pegs its currency to another currency cannot pursue an autonomous monetary policy. The WAEMU and the CEMAC, two currency unions mainly composed of poor countries, are de facto subordinated to the monetary policy of another currency union, the Eurozone, which comprises highly developed countries with totally different priorities and needs. The consequences of this were well explained by the Nobel prize winner Robert Mundell in 1997:

‘If a small country unilaterally fixes its currency to a larger neighbour, it in effect transfers policy sovereignty to that larger neighbour. The fixing country loses sovereignty because it no longer controls its own monetary destiny; the larger country gains sovereignty because it manages a larger currency area and gains more “clout” in the international monetary system.’

Moreover, as the countries of the Eurozone know all too well, the fixed exchange rate means that:

’The 15 member countries of the franc zone, taken individually, are deprived of the possibility of using the exchange rate to soften the effects of economic shocks or to improve the price competitiveness of local products. And this in a continent where shocks of every kind – political (coups d’état, wars, social tensions etc), climatic (rainfall variations, droughts, floods etc) and economic (volatility of the prices of primary products, interest rates on the foreign debt, capital flows etc) – are commonplace. Thus, to deal with adverse shocks, the countries of the franc zone have only one option, in the absence of fiscal transfers: “internal devaluation”, that is, an adjustment of internal prices that passes through the reduction of labour income and public spending, tax increases and the decline in economic activity.’

A cursory glance at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) statistics confirms that the fixed exchange rate has proven to be a ruinous choice for the African countries: since 2000, the countries of Sub-Saharan Africa operating in a fixed-exchange-rate system have experienced economic growth between one and two percentage points below that of those countries with a flexible exchange rate. This gap is due. in particular, to ‘the lower growth of the member countries of the franc area’, states the IMF. As Sylla notes: ‘[E]xperience shows that nations like Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria, which, post-independence, withdrew from the franc zone and [minted] their own currency, are stronger economically than any user of the CFA franc’.

A third handicap follows from the first two: the under-financing of the economies of the franc zone. In order to avoid depleting their foreign reserves, which would jeopardise the fixed parity, the central banks of the franc zone must limit the growth of domestic credit (the volume of bank loans made available to governments, businesses and households). Moreover, since 1999, the countries of the franc zone are subject to the same budgetary constraints (strict deficit- and debt-to-GDP limits) of the Eurozone countries, as well as to the prohibition of monetary financing.

One of the consequences of this is that African countries must turn to foreign countries – often France itself – to finance their development, contracting foreign currency loans at very high interest rates. This mechanism further tightens the noose around African countries, with dramatic social consequences. As Pigeaud and Sylla report, ‘every dollar spent in Africa on servicing the debt translates into a 29 per cent reduction in healthcare expenditure (which, in more tragic terms, can be translated economically as follows: every $140,000 devoted to servicing the debt, a child dies)’.

Such under-financing clearly penalises the economic growth of African countries, as admitted even by economists supportive of the CFA franc, such as Sylviane Guillaumont Jeanneney: ‘The weak growth of the UEMOA is partly explained by a lower investment rate compared to other regions of Africa.’ The Senegalese economist Demba Moussa Dembélé, a critic of the CFA system, is more unforgiving. Because of the fixed parity and the restrictive policy of the BCEAO, he explains, ‘we are subject to the imperatives of the European Central Bank, which is obsessed with fiscal discipline and the fight against inflation, while the priorities of our underdeveloped countries should be employment, investment in productive capacity, and the creation of infrastructures. This implies a greater distribution of credit to the private and public sector.’

Lastly, the final handicap: the free movement of capital. This factor, Pigeaud and Sylla write, ‘considerably hinders the development of the African countries, translating in most cases into a financial bleed-out… When fundamental sectors of the economy are under the control of foreign capital, as is the case in most countries of the franc zone, the free movement of capital acts as a mechanism for draining African resources towards the rest of the world: a legalised looting.’ This phenomenon can be observed above all in those countries most endowed with natural resources: Ivory Coast, Cameroon, Congo, Gabon and Equatorial Guinea. Suffice to say that between 2000 and 2009 the net transfers of income to the rest of the world – which include the profits and dividends of the multinationals operating in those countries – amounted to roughly 43 per cent of GDP for Equatorial Guinea and 30 per cent percent of GDP for the Congo.

The result of these ‘four handicaps’ is that, although some countries of the franc zone (especially those richer in raw materials) have experienced a rather strong annual GDP growth rate in recent years, an analysis of the long-term statistics shows that the real GDP per capita – or ‘average income’ – of most countries of the zone is equal to or lower than that recorded in the 1970s or 1960s. It is therefore not surprising that socio-economic progress in the franc zone has been very limited: 12 of the 15 African states of the franc zone are classified as ‘Low Human Development’ countries, the last category in the Human Development Index (HDI) developed by the United Nations Development Program. In 2015, the last four places in the HDI ranking went to Burkina Faso, Chad, Niger and the Central African Republic, all of which are part of the franc zone. Furthermore, ten states of the franc zone are part of what the United Nations calls the ‘Least Developed Countries’.

‘Obviously, the CFA franc is not the only cause of these countries’ underdevelopment and other African countries have not necessarily “fared better”’, Pigeaud and Sylla note. ‘But the claim that the CFA franc has “promoted” growth and development in the area is patently false’:

‘In all the CFA countries, the underdevelopment of human potential and productive capacities is the norm. The CFA system has not stimulated neither the commercial integration of its members, nor their economic development or their economic attractiveness. On the contrary, it has deprived countries of the ability to conduct an autonomous monetary policy, paralysed their productive dynamics through the limitation of bank credit, penalised the competitiveness of local production through structurally overvalued exchange rates and facilitated destabilising forms of capital outflow, with dramatic social consequences.’

An unsustainable statu quo

In light of the above, one might ask why the countries of the franc zone don’t simply abandon the CFA system. A first response is that, even today, France has no qualms about using its power to quell any challenge to the system.

A particularly striking example of this occurred recently in the Ivory Coast. It all started after the 2010 presidential elections, when the country found itself with two presidents: Laurent Gbagbo, the outgoing president, had been recognised as the legitimate winner of the elections by the Ivorian Constitutional Council and had therefore stayed in power; Alassane Ouattara was considered the winner by the ‘international community’. Wanting to see Ouattara in power, the then French president Nicolas Sarkozy immediately resorted to the CFA apparatus to put pressure on Gbagbo.

To begin with, the French government cajoled the BCEAO – the central bank of the CEMAC, the monetary union of which the Ivory Coast is a part – into preventing the Ivorian government from accessing its accounts at the BCEAO and closing down the Ivorian branches of the BCEAO. Then, the bank’s board forced its governor to resign, accusing him of being too complacent with the Ivorian authorities. Shortly afterwards, the French government also forced the French banks operating in the country to stop their activities. But Gbagbo refused to give in.

At that point, France moved to the next stage. It mobilised its invisible weapon: the operating account. With the assistance of the BCEAO, the French Ministry of Finance suspended the country’s payment and exchange operations: effectively, all commercial and financial transactions between the Ivory Coast and the rest of the world were blocked. The Ivorian companies found themselves unable to export or import. ‘The French authorities’, Pigeaud and Sylla write, ‘demonstrated that the operating account could become a formidable instrument of repression: through it, France was able to organise a frighteningly effective financial embargo.’

As Justin Koné Katinan, Laurent Gbagbo’s budget minister at the time, would later say: ‘I witnessed the reality of Franco-African imperialism with my own eyes. I saw how our financial systems continue to be totally under France’s dominion, [and operated] in the exclusive interest of France. I saw how a single official in France can block an entire country.’

Faced with France’s financial embargo, the Ivorian administration began to take steps to create its own national currency. At that point, France threw away its mask: it mobilised its armed forces present in the Ivory Coast – as in other countries of the franc zone – and overthrew the government. End of story.

The aforementioned episode shows just how simplistic the claims that the countries of the franc zone adhere ‘voluntarily’ to the CFA system really are.

That said, there’s no doubt that the African elites of the franc zone, with few exceptions, support the CFA system. This is hardly surprising. After all, ‘they were put into power – and they continue to exercise it – with Paris’s support’, Pigeaud and Sylla note.

African leaders know that as long as they continue to facilitate the operations of the French state and don’t challenge the CFA franc, they will enjoy the ‘tutelage’ of the former colonial power, including against their citizens and opponents. Furthermore, despite being designed to serve primarily the interests of France, the CFA system offers certain economic benefits to some African social groups.

The pegging of the CFA franc to the euro, a strong currency, allows importers in African countries, for example, to buy products at an advantageous price that allows them to easily compete with local producers. At the same time, it provides the local middle and affluent classes with an artificially high international purchasing power that gives them the opportunity to access the same goods and services as their Western counterparts. Finally, the free movement of capital allows the wealthy elites of those countries to stash their fortunes abroad, more or less legally.

However, as mentioned at the beginning, things are starting to change. As Pigeaud and Sylla write: ‘The demands to put an end to the CFA franc are multiplying and the pressure is increasing.’ More and more African economists, intellectuals, artists and social movements are calling for an end to monetary colonialism. Their arguments, the authors note, ‘have a certain echo in public opinion, increasingly aware that, without monetary independence, the states of the franc zone will continue to remain subject to France… Without necessarily knowing all the technical details of the case, a growing number of African citizens are realising that it will be impossible to freely determine their own destiny without true monetary sovereignty.’

A warning that even the peoples of the Eurozone – the only other monetary union in the world comprising formally sovereign states – would do well to heed.”

joseba says:

Dinero, imperialismo y desarrollo

http://www.redmmt.es/dinero-imperialismo-y-desarrollo/

joseba says:

Introduction – The Last Colonial Currency: A History of the CFA Franc – Part 1

http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=43904

joseba says:

Introduction – The Last Colonial Currency: A History of the CFA Franc – Part 2

http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=44027

joseba says:

http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=43904#comment-65938

Derek Henry

Tuesday, January 7, 2020

Superb Bill,

I couldn’t get Scotland out of my mind while I was reading that. Trying to break free from London eager to be trapped by Brussels.

And Michael Hudson’ s quote ringing in my ears from every paragraph.

“ The idea that the euro has “failed” is dangerously naive. The euro is doing exactly what its progenitor – and the wealthy 1%-ers who adopted it – predicted and planned for it to do. … Removing a government’s control over currency would prevent nasty little elected officials from using Keynesian monetary and fiscal juice to pull a nation out of recession. “It puts monetary policy out of the reach of politicians. Without fiscal policy, the only way nations can keep jobs is by the competitive reduction of rules on business. Hence, currency union is class war by other means. “

joseba says:

Introduction – The Last Colonial Currency: A History of the CFA Franc – Part 3

http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=44038