Randall Wray-ren Does America Need Global Savings to Finance Its Fiscal and Trade Deficits?

(https://americanaffairsjournal.org/2019/02/does-america-need-global-savings-to-finance-its-fiscal-and-trade-deficits/#.XG8e3s69Szk.twitter)

(i) Ortodoxia1

(ii) Heterodoxia2

Defizit bikoitza: ikuspegi arrunta

(Popular Views on Twin Deficits)

(iii) Defizit bikoitza3

(iv) Segida4

Sektore balantzeen ispilu irudia

(The Mirror Image of Sectoral Balances)

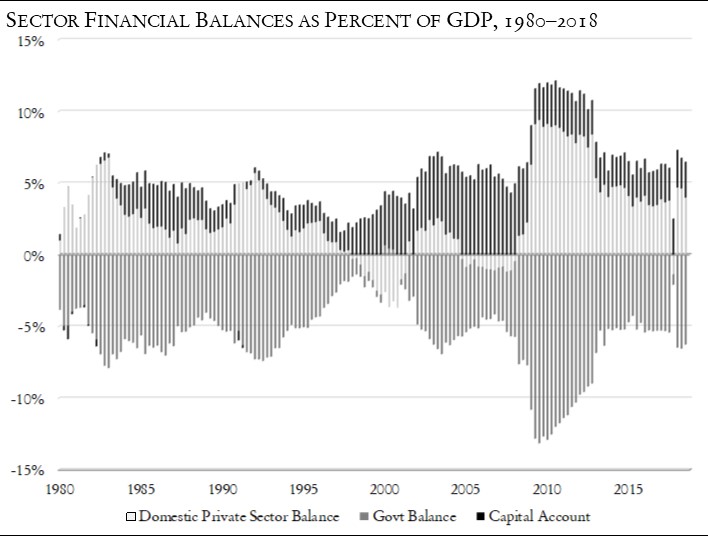

The following graph presents the three main sectoral balances for the United States: the domestic private balance (households and firms), the domestic government balance (all levels of government), and the foreign balance (the rest of the world). No, your eyes don’t lie: it is a mirror image. Balances balance.

(v) Ispilu irudia5

(vi) Gobernu federaleko sektorea eta sektore pribatua

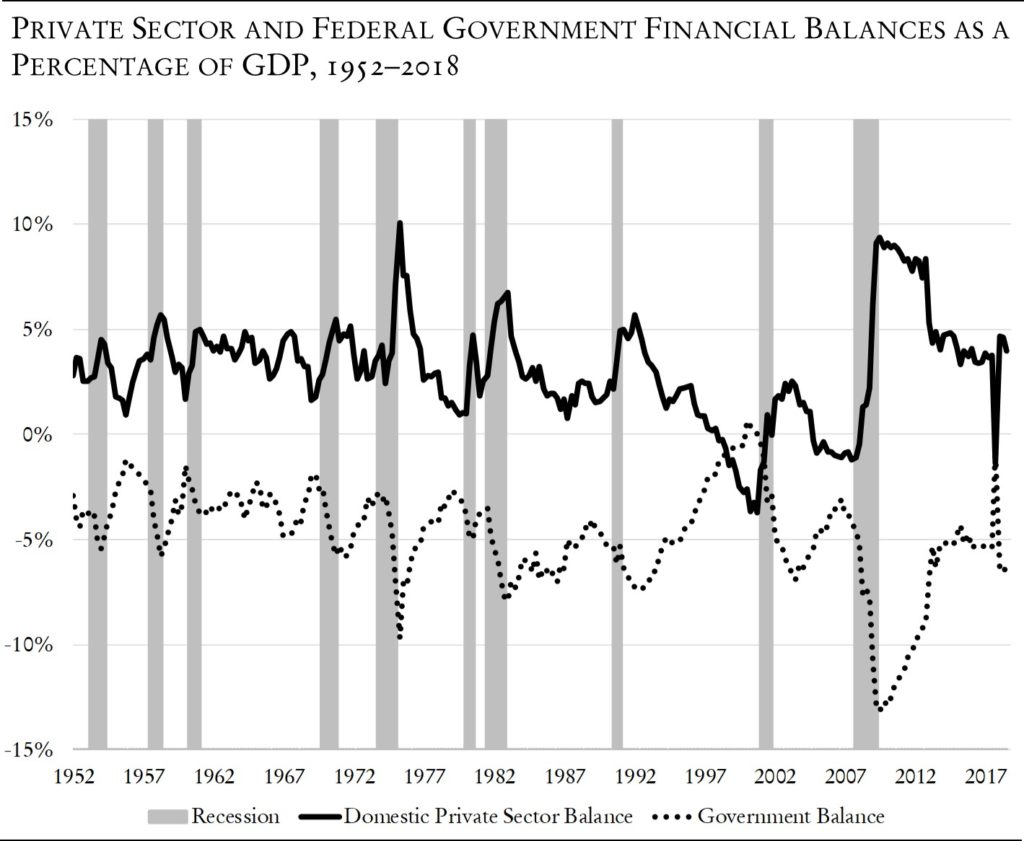

The next graph plots only the federal government and domestic private sectors—similar to the Journal’s graph—nearly a mirror image, indicating that the fluctuation of the foreign sector balance does not have much of a net impact on domestic sector balances. The graph also shows recessions as shaded areas: note how “improvements” in the federal government balance are almost always followed by a recession. Hold that thought.

(vii) Segida6

Aurrekontu defizitak, merkataritza defizitak eta atzerriko maileguak

(Budget Deficits, Trade Deficits, and Foreign Lending)

(viii) Aurrezkiak, mailegu hartzaileak eta mailegu emaileak (ortodoxiak dioena)7

(ix) Historia pixka bat8

Not only is there is a strong correlation between U.S. current account deficits and foreign holdings, but it is apparent that the relationship is largely driven by foreign official holdings—by central banks—which closely track the rise of the current account deficit (amounting to approximately three-quarters of foreign holdings by the end of 2009) and not predominantly by private sector holdings.

(x) AEBko Altxor Publikoa, Japonia eta Txina9

(xi) Akzio-jabetza eta ustezko iritziak. Aldaketak FED-eko kontuetan10

Mailegatzea, aurreztea eta kartera esleipena

(Lending, Saving, and Portfolio Allocation)

(xii) Aurrezkiak eta mailegatzeko fondoak: bankuek zuzenki finantza sortzen dute beraiek maileguak luzatzen dituztenean11

Nola finantzatzen dira aurrekontu defizitak eta merkataritza defizitak?

(How Are Budget Deficits and Trade Deficits Financed?)

(xiii) Gobernu defiziten finantzaketa, James K. Galbraith12

(xiv) Aspaldiko egunetan, Henry Ford eta Thomas Edison13

(xv) Beardsley Ruml eta Abba Lerner14

Zeinek zein finantzatzen du?

(Who Finances Whom?)

(xvi) Aurreztea eta mailegatzea, nazio mailan eta nazioarteko mailan15

Arazo errealei aurre eginez

(Addressing the Real Problems)

(xvi) Finantza krisia, finantza-austeritatea, irtenbidea. Gobernuaren politika16

“We need a sound understanding of financial balances and sovereign currency”

1 Ingelesez: “It is frequently argued that America’s twin deficits—the government budget deficit and the trade deficit—result from profligate spending by the government and private sectors. This excess domestic spending, moreover, must be financed by global savings, putting America on an unsustainable debt path. Problems are compounded as the U.S. demand for savings can push up interest rates, crowding out investment and causing the dollar to appreciate. American investment and exports are thereby depressed, slowing the growth of productive capacity. At some point, global savers will cut the flow of dollars to America’s borrowers, making it difficult to continue to finance spending. As spending falls and the economy struggles, there could be a run out of the dollar—causing its value to collapse and raising the prices of imports. Even if no run occurs, the dollar’s days as the dominant international reserve currency are numbered because of America’s excessive reliance on foreign saving. According to this argument, the best solution would be to ramp up domestic saving to replace the reliance on foreigners.”

2 Ingelesez: “This article will offer an alternative view: American “profligacy” is the source of global dollar savings, and, consequently, there is no danger that the United States might run out of dollars to finance its spending. On the other hand, America does face substantial problems generated by excessive inequality and by an overgrown financial sector that misdirects credit.

We need to explore an alternative approach to finance as well as to financial balances. While the private sector’s indebtedness is dangerously high, neither the government deficit nor the current account deficit should raise concern. The key issue is to use government policy to promote the capital development of the economy—that is, to refocus government spending as well as financial market activity on the productive sphere of our economy.”

3 Ingelesez: “President Trump promised to do something about America’s chronic trade deficit—which, like the federal budget deficit, has ebbed and flowed since the days of Reaganomics. The “twin deficits” are often linked in both the public mind and in mainstream economic theory. The popular explanation points to profligate spending, with the trade deficit linked to excessive consumption by American households and the budget deficit linked to runaway government spending—especially on entitlements. The more sophisticated argument is that budget deficits drive up interest rates, causing the dollar to appreciate and thereby reducing U.S. competitiveness. Of course, there are also other factors that are claimed to play a role in producing a trade deficit, including currency manipulation (especially by China), competition by low-wage labor (Asia more generally), and other unfair trade practices (everywhere). Democrats would also blame big tax cuts for the rich and offshore tax arbitrage by corporations for chronic budget deficits.

The link between budget deficits and interest rates is based on the old loanable funds argument: there is a limited supply of savings available for lending. Government borrowing competes with private borrowers for scarce funds, pushing up rates. If we could encourage more domestic saving, this should relieve pressure on rates, lower the dollar’s value, and reduce the trade deficit. At the same time, lower interest rates would reduce government payments on the debt and thereby reduce the budget deficit—at least marginally.

Former Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke provided a new twist on this argument, blaming a glut of global savings for both the U.S. current account deficit and for the bubbles whose bursting led to the global financial crisis (GFC). The story goes like this: High saving rates abroad (especially in Asia and among the oil-exporting nations) led to excess liquidity sloshing around in global financial markets. Much of this found its way to the United States and was loaned to American consumers and the government. This drove stock, commodity, and real estate market bubbles, as well as higher imports.

David P. Goldman recently updated the argument by bringing in demographics: most countries are aging rapidly, which encourages high saving rates for impending retirement; this generates current account surpluses as output is exported.1 At the same time, global savers look for safe investments for retirement. The United States bucks the trend, however. Goldman shows that we run current account deficits despite a moderately high ratio of aging citizens, meaning that the country is dissaving rather than preparing for the retirement of the baby boomers—a wave that has already started.

The Trump tariffs are supposed to help, raising the costs of imports to discourage unfair trade practices among our competitors. It is far too early to tell if they are working, but recent data doesn’t indicate much impact. One report by the New York Fed, however, has delivered a bit of seemingly good news—while the Trump tax cut has increased the budget deficit, it has also boosted U.S. saving:

The federal tax cut and the increase in federal spending at the beginning of 2018 substantially increased the government deficit, requiring a jump in the amount of Treasury securities needed to fund the gap. One question is whether the government will have to rely on foreign investors to buy these securities. Data for the first half of 2018 are available and, so far, the country has not had to increase the pace of borrowing from abroad. The current account balance, which measures how much the United States borrows from the rest of the world, has been essentially unchanged. Instead, the tax cut has boosted private saving, allowing the United States to finance the higher federal government deficit without increasing the amount borrowed from foreign investors.2

Higher saving reduces the risk that interest rates will rise (worsening the trade deficit), thereby attenuating the twin deficits effect. There’s even more good news: we’ve cut our dependence on foreign savers since the GFC:

The nation was borrowing amounts equal to around 5.0 percent of GDP in the run-up to the global financial crisis. In recent years, however, borrowing from abroad has been much lower, averaging less than 2.5 percent of GDP a year. . . . The most recent observation is for the second quarter of 2018, when borrowing fell to 2.0 percent of GDP.

Before you get too excited, never forget that economics is the dismal science:

[T]he key driver of higher U.S. saving after the Great Recession was the improvement in federal government saving. Taxes were cut and temporary spending increases reduced government saving during the downturn, but spending was subsequently cut back, a number of tax cuts were eliminated, and a growing economy increased tax revenues. Government saving thus became substantially less negative and helped raise total U.S. saving. However, a turnaround caused by the 2018 fiscal actions on federal government saving is evident in the latest data, with dissaving deteriorating from 2.0 percent of GDP in the first half of 2017 to 3.4 percent of GDP in the first half of 2018. In dollars, government saving dropped by around $300 billion (annualized rate) from the year-ago level.”

4 Ingelesez: “In other words, while our households are saving more, our government is saving less (running a larger budget deficit). This is precisely the opposite of the situation in 1999, when the Wall Street Journal ran a front-page double feature on U.S. savings rates. At that time, the government was running a surplus, adding to national saving, while the private sector ran up deficits, reducing national savings. The headlines of each story ran “Budget Surpluses May Wipe Out the Federal Debt” and “Few Households Heed Washington’s Urging for Bigger Nest Eggs: Saving Rate Declines Again,” respectively. The Journal helpfully put a graph in the same issue that showed government savings rising well into positive territory while the private sector’s saving dipped ever more deeply—what looked like a mirror image. The header to the graph proclaimed, “As the government saves, the people spend.”

And that’s what it was—a mirror image tied to an unrecognized accounting identity. This time around, as we’ll see, the mirror image shows the government saving less, and the households saving more. And it must be that way: if one goes up the other must go down.”

5 Ingelesez: “The government sector is almost always in deficit (spending more than revenues). The only significant exception is the mid-1990s—the Clinton years when the government ran a surplus. The domestic private sector is almost always in surplus—the exception is (again, surprise!) the Clinton years and the housing bubble of the mid-2000s. And then there is the foreign sector; here it is shown as the U.S. capital account balance, which is the (reverse) analogue to the current account balance. When the United States runs a current account deficit, that will be recorded as a positive capital account surplus as the rest of the world runs a surplus against the United States.

For the arithmetically inclined, the graph depicts a macroeconomic identity:

(Domestic private income − domestic private spending) + (domestic government income − domestic government spending) + (United States current account balance with the rest of the world) = zero.

This can be approximated as:

(S − I) + (T − G) + (M − X) = 0

S is domestic saving, I is domestic investment, T is tax revenue (all levels of government), G is government spending (at all levels), X is exports, and M is imports. The first term in parentheses is the private sector balance; the second is the government sector balance; and the third is the foreign sector balance. What this means is that if one sector runs a deficit (spends more than its income), at least one other must run a surplus (spends less than its income). It is related to the identity that for every creditor there must be a debtor.”

6 Ingelesez: “In the Keynesian terms of the old macroeconomics textbooks, we could restate this identity in the form of “leakages and injections”: the leakages (private sector surpluses, government surpluses, current account deficits) must equal the injections (private sector deficits, government deficits, current account surpluses). For example, a private sector surplus (leakage) implies that the government sector is running a deficit (injection) and/or that the foreign sector is running a deficit (injection—meaning the United States has a current account surplus). It is possible to run a private sector surplus and a current account deficit so long as the government deficit is larger than the private sector surplus. What matters is the sum of the three.

Aside from its amazing symmetry, the other noticeable thing about the graph is the striking anomaly of the decade from approximately 1997 to 2007. The first half experienced the very unusual government budget surplus while the private sector experienced two unusual camel humps of large deficits over the decade—punctuated ever so briefly by a surplus in the Bush recession. The first of these humps coincided precisely with the Clinton budget surpluses. But, holding the current account deficit constant, a move to a budget surplus had to be matched by a movement to a private sector deficit.

To be sure, the current account surplus was not constant during the period in which the private sector ran a deficit, though it was stable enough not to offset the movement of the budget to surplus. In the second of the camel’s humps, the longer-term growth of the current account deficit was so large that the smaller turn of the private sector toward deficit implied an offsetting movement of the government’s budget toward only smaller deficits.

Sectoral balances are derived from identities. They are true by definition. Alone they do not tell us anything about causation. But they keep us honest.

As the first graph shows, there have been large current account deficits (capital account surpluses) since the Reagan years. That is to say, from Reagan through a couple of Bushes and across a Clinton and an Obama—and, I dare say, across a one-term or even a two-term Trump, the United States has run and will continue to run a current account deficit. That means the rest of the world runs a surplus, day in, day out. That might change someday, but for now we should expect to have a current account deficit—regardless of the party in power, regardless of the value of the dollar, regardless of monetary policy, regardless of aging and saving propensities, regardless of the size of the budget deficit, regardless of the rate of inflation, regardless of business cycle swings (even those as severe as the dot-com and housing bubble busts), and regardless of foreign currency manipulation or unfair trade policies. We can take a current account deficit as a given, although with some relatively constrained fluctuations in size.

Now, if that is true (and it is), then it is literally impossible for the U.S. government sector and the private sector to both run, simultaneously, surpluses. Regardless of the causes behind the balances of each, for one of these to have a surplus, the other one must have a deficit that equals the sum of that surplus plus the current account deficit (or, alternatively, the rest-of-world surplus). That is simple arithmetic.

What this means is that the old Wall Street Journal double feature failed to acknowledge the link between the movement of the budget toward surplus (adding to saving) and the declining private sector savings rate. To borrow a phrase: TWNA—there was no alternative. Berating the private sector for its profligacy would make no more sense than berating the government sector for its prudence. Indeed, the government’s contribution to national saving was simply the other side of the coin of the private sector’s dissaving. Balances do balance.

The current account deficit might someday reverse. I do not know what might do that, but I’m sure that U.S. policy alone will not. Indeed, I think that it almost certainly has more to do with the policies adopted by the rest of the world—and if that is true, it is largely out of our hands. In any case, that deficit is amazingly robust.

The budget deficit is also robust, so it is worth exploring any possible link between the two. It is generally believed—as indicated in the previous section—that the two are linked not simply by an identity but rather through causal connections. Let’s explore those connections.”

7 Ingelesez: “The scarcity of domestic savings is supposed to force American borrowers to seek loans abroad. Moreover, once we have come to rely on foreign lending, we are exposed to the risk that finicky global savers might shut off the loans. How would Uncle Sam continue to finance his profligate spending? Where would American households obtain the wherewithal to buy their favorite imports? As the flow of international savings is withdrawn, won’t U.S. interest rates spike? And if there is a run out of the dollar, how will America deal with a collapsing exchange rate that puts key inputs like oil out of reach for consumers and industry?”

8 Ingelesez: “Let’s begin again with some history. Before the 1970s, foreign holdings of U.S. Treasuries were small—accounting for less than 5 percent of federal debt. Thereafter, the percent held abroad rose to around 20 percent in the 1990s and to about 30 percent in 2000. Right after the GFC, foreigners held nearly half the federal debt, but that has since fallen to around 40 percent today. Since the early 2000s, the relative importance of Japanese holdings has given ground to China’s increasingly large holdings. The other biggest holders are exporters (including Taiwan, Hong Kong, and oil producers) to the United States as well as banking centers (in the Caribbean, Luxembourg, and Switzerland). The following chart sheds more light on the relation.”

9 Ingelesez: “The following two graphs compare U.S. Treasury holdings with U.S. bilateral trade balances against Japan and China. The correlation is obvious: countries with large trade surpluses against the United States accumulate large quantities of U.S. Treasuries. This isn’t hard to explain: these countries’ exporters receive payment in dollars that they exchange for domestic currency deposits. Their banks receive dollar claims on U.S. banks that are converted to yen or renminbi reserves at their central banks. The Fed clears accounts—debiting reserve deposits of domestic banks—and the foreign central banks get credits to their reserve accounts at the Fed. These are converted to U.S. Treasuries to earn higher interest rates.”

10 Ingelesez: “To be sure, the trade balance is not the only determinant of holdings because trade in goods and services is just part of the overall balance countries have with the United States—there are also factor payments, remittances, and purchases and sales of assets. (This is why small banking centers are also large holders of U.S. Treasuries.) Thus, the correlation is not perfect, but it still accounts for a large portion of holdings. That also helps explain why most foreign holdings are in official accounts—reflecting the fact that foreign holdings are produced by the movement of reserves at the Fed to foreign central banks, which then purchase Treasuries to earn interest.

It is frequently claimed that the United States is in a more precarious position relative to that of Japan, because much of U.S. federal government debt is held outside the country, while virtually all of Japan’s is held domestically. The U.S. government is said to have become dependent on lending by Japan and China—and subject to any potential refusal by these countries to continue to “finance” U.S. government deficits. But, given that Japan runs current account surpluses, it is no surprise that there are few yen-denominated external claims to be converted to Japanese government securities.

Again, trade is not the only means by which one could obtain Japanese securities—for example, one could also borrow yen in foreign exchange markets. Nor would a country with a trade surplus against the United States have to hold U.S. Treasuries: it could sell them to buy another asset, shifting the Treasuries to another portfolio—perhaps to another foreign holder.

But note that if the United States runs persistent current account deficits, this will be reflected in its capital account surpluses: foreign entities will hold dollar claims against the United States. Even if the U.S. government were to run surpluses, Japanese and Chinese current account surpluses against the United States would lead to accumulation of dollar claims, some of which would take the form of U.S. Treasuries. That is because they’d want to diversify some of their accumulations of dollar-denominated assets into the safest ones. And it is likely that they would still want to buy U.S. Treasuries even if the government were not providing new issues. In that case, the proportion of U.S. Treasuries held abroad would rise even in the absence of U.S. government budget deficits.

What all this means is that the holding of U.S. Treasuries abroad has more to do with the U.S. current account deficit than with the U.S. budget deficit. It is the deficit in trade that generates large dollar claims—some of which are held in the form of Treasuries. It is true that if the U.S. government had never run a deficit, there would be no U.S. Treasuries held abroad (or domestically!), but that misses the more important connection between trade and foreign holdings. Countries that export to the United States will end up with dollar claims, initially in the form of credits to central bank accounts at the Fed. They can use these reserves to buy imports or other financial assets (if from the United States, the reserves held at the Fed are debited; if from another country, the reserves are simply shifted from one country’s account to another country’s account at the Fed). As the dollar is the major international reserve currency, it is useful to accumulate dollar claims. And since many countries either peg or manage their exchange rates, the accumulation of dollar reserves is an imperative.”

11 Ingelesez: “There is a long-outdated view that saving is the source of funds for lending. At the individual level it rings true: If I earned $200 but only spent $150, I have $50 that I might lend to you. I’d charge you some interest to cover the risk that I might need the $50 before you repay me, and for the risk you might not repay at all. In the aggregate, we get a supply of available funds from savers and a demand for funds from borrowers. We could imagine that both supply and demand are sensitive to the interest to be earned (by savers, a positive function of rates) and paid (by borrowers, a negative function of rates), with an equilibrium market rate determined by the intersection of supply and demand curves. This, in a nutshell, is the loanable funds theory.

We can add banks as financial intermediaries that accept deposits of savers and lend them out to borrowers. By diversifying across borrowers, the banks can reduce risks and thereby lower lending rates. That is the traditional view of banks. We could go further by noting that banks don’t have to keep cash equal to deposits on hand for possible withdrawals since depositors will not convert all deposits to cash at the same time. That allows for a “deposit multiplier” or “fractional reserve” system. All of this is taught in the principles of macroeconomics textbooks.

It is also wrong. The loanable funds theory was skewered by John Maynard Keynes in 1936. It is undermined by the paradox of thrift: aggregating up from individual saving behavior falsely presumes that national income is invariant to saving. At the extreme, assume an economy in which no one who receives income spends it, as everyone saves all income. Then aggregate spending is zero. But we know from national accounting that income is equal to spending (and, indeed, is determined by spending since there is no source of income other than spending). So there is no income to save—which means that saving, too, is zero.

The paradox of thrift is just one example of the more general “fallacy of composition.” While it is true that I can increase my saving without hurting my income, if everyone increases saving it will affect aggregate income so that saving might not rise. What is true at the individual level is often not true at the aggregate.

Keynes went on to distinguish two distinct steps in the saving decision. First is the decision to reduce consumption (increase saving). Second is the decision over how to hold saving. The first step is largely a function of income and will normally affect income—as reducing consumption spending will lower total expenditures and thus income. He thus rejected the loanable funds explanation of the determination of interest rates—saving directly affects income, not interest rates.

It is the second step that affects interest rates: if one prefers to hold saving in the form of cash (rather than in the form of other financial or real assets), this will affect asset prices and hence interest rates. This led Keynes to his alternative to the loanable funds theory, liquidity preference theory. Briefly, interest is the reward for giving up liquidity; when liquidity preference is high, the premium (interest rate) that must be paid to get savers to hold assets that are less liquid than cash must be higher. There is thus a spectrum of interest rates, with rates of one asset class relative to those of another determined by perceived differences in liquidity.

To be sure, other factors play a role in interest rate determination—including relative riskiness of assets, expected changes to monetary policy, and duration.3 It is also possible for quantities of assets relative to demand to affect prices and interest rates (if desired long-term bonds are scarce, for example, their prices can be pushed up). But what is important is that rate determination comes in the second step of the saving decision. The first step would affect rates only through changing the expectations that influence the desired portfolio in which saving would be held.

Keynes’s logic seems to raise a problem: if income must come before saving, and spending must come before income, how does spending get financed? More specifically, traditional theory presumed that saving finances investment, and traditional theory had already acknowledged the significance of investment as a driver of the capitalist system, as did Keynes’s own theory of effective demand. What Keynes did was to reverse the causal order: investment creates saving—or, more precisely, investment creates the income that can be saved. But if that is true, how does investment get financed in the first place? If the traditional view of banks as intermediaries were true—requiring saving that could be lent through bank intermediation—we have a problem.

Keynes’s own General Theory didn’t provide a clear answer, though his earlier work (in the Treatise on Money) as well as his response to critics after 1936 did. The short answer is that banks create finance directly when they make loans. Unfortunately, his explanation was not picked up by most economists—even his followers who adopted his reversal of the investment-saving relationship did not generally abandon the old intermediation view of banks.

It was left largely to economists on the fringes of respectability (post-Keynesians, institutionalists, and, later, modern monetary theorists) to reconstruct an alternative view over the past three or four decades. Fortunately, this alternative has now been adopted by many and perhaps a majority of macroeconomists (even though most textbooks lag behind). To put it succinctly, banks do not lend out savings but rather lend their own liabilities (i.e., deposits). As Paul Sheard explained recently in a report for Standard & Poor’s:

Banks lend by simultaneously creating a loan asset and a deposit liability on their balance sheet. That is why it is called credit “creation”—credit is created literally out of thin air (or with the stroke of a keyboard). The loan is not created out of reserves. And the loan is not created out of deposits: Loans create deposits, not the other way around. Then the deposits need a certain amount of reserves to be held against them, and the central bank supplies them.4

Or, as post-Keynesians like me have been saying since the 1980s, “loans make deposits and deposits make reserves,” not in some metaphysical sense but as a causal sequence. These are all entries on balance sheets. A “loan” consists of an entry on the liability side of the borrower’s balance sheet and an offsetting entry on the asset side of a bank; a “deposit” is the counterpart entry on the bank’s liability side and on the borrower’s asset side. (In practice, when a bank makes a loan it is usually making a payment for the borrower, so the offsetting deposit will be a credit to the seller’s deposit—say, for the car dealer or for the home seller.) If the bank needs reserves for clearing or to meet reserve requirements (calculated with a lag), it will go to the federal funds market to borrow them—or if there are no excess reserves available it will go directly to the Fed’s discount window. But obtaining reserves follows the lending process, rather than preceding it as in the “fractional reserve” or deposit multiplier narratives.”

12 Ingelesez: “What does this mean for the topic at hand, namely, for the “twin deficits” and “global savings excess” arguments? Let’s tackle the question of the financing of government deficits first. Just as there is a tremendous amount of misunderstanding about bank lending, there is an even more important misunderstanding of government finance.

The traditional view is that government has three choices when it comes to spending: use tax revenue, borrow, or print money. The first is constrained by political will, taxpayer resistance, and the performance of the economy (tax revenue falls sharply in downturns). The second is constrained by “bond vigilantes,” including those in foreign nations that Uncle Sam relies upon. And the third is a recipe for the doom of hyperinflation.

While this view seems reasonable, it only applies to a non-sovereign government—one that does not issue its own currency. Sovereign governments spend by crediting accounts. Just as a bank does not really take in deposits in order to lend, a sovereign government does not really spend tax revenue or borrow its own currency. As James K. Galbraith put it:

When government spends or lends, it does so by adding numbers to private bank accounts. When it taxes, it marks those same accounts down. When it borrows, it shifts funds from a demand deposit (called a reserve account) to savings (called a securities account). And that for practical purposes is all there is.5”

13 Ingelesez: “In the old days, before there were central banks, it was all quite simple. A sovereign government that wanted to spend would mint coins, print paper money, or cut tally sticks to finance its spending. It used taxes to “redeem” the currency—that is, to take it out of circulation. Notes and tally sticks were almost always burned on receipt. Coins could be reissued, but also often were melted for recoining (or simply restamped to indicate a new denomination). Redemption helped to reassure the public that the currency would not remain in circulation where it could cause inflation. Historically, governments issued a variety of paper notes and bills—some were “current” while others had maturity dates; some paid interest while others did not.6

To put it simply: government spends (or lends) currency (cash and reserves) before receiving it in payment of taxes or purchases of its debt (bills and bonds). This was obvious in the early days of America up through the greenback era, as Farley Grubb, one of the premier historians of American colonial currency, makes clear.7 Our colonies were the first significant issuers of paper currencies in the West, and, indeed, those were the only paper monies circulating in the New World because there were no banks issuing notes in the colonies. Use of paper money was due to necessity—the British crown reserved the right of coinage. Strapped for cash to finance spending, the colonial governments experimented with paper currencies.

Grubb notes that there were a wide variety of paper notes issued by the colonies: some were legal tender, others were not; some paid interest, others did not; some colonial governments spent the notes directly on “soldiers’ pay, military provisions, salaries, and so on”; and some also “loaned bills on interest to their citizens, who secured these loans by pledging their lands as collateral.”

Grubb has shown that each colonial act authorizing the issue of paper notes also imposed a tax to “redeem” them. The effect of the redemption was to take notes out of circulation—the tax “revenues” were burned, not spent8—to prevent inflation or at least to allay the fears of inflation. The taxes were called “redemption taxes” in the authorizing acts—indicating that the process was well understood. Note also the logic behind the process: the colonial governments had to spend notes before they could receive them in payment of redemption taxes. It would have made no sense to impose the taxes and wait for the revenues to pour in before spending the notes.

With the advent of central banks, sovereign finance gradually evolved to the system we have today. Modern governments make and receive all payments through their central banks. In addition, bond issues, redemptions, and (now) repos and reverse repos are handled by central banks. This has made the operations less transparent (with several degrees of separation between the government and its citizens) even as it has made them less disruptive. Over many decades, the Treasury and central bank have learned how to minimize the effects of fiscal operations (spending and taxing) on private banks (that is, reserve holdings and interest rates), and have streamlined bond operations. That, in turn, has made it easier for central banks to manage overnight interest rates—which have become the main policy instrument of central banking. On the other hand, the increased opacity has allowed the myths of government budget constraints to shroud understanding.

But along the way, some were able to pierce the fog. In 1921 Henry Ford proposed a major energy infrastructure project (at Muscle Shoals, Alabama) to be funded by government through the issue of currency. A century earlier, this would have been accepted as sensible and routine. But by Ford’s time, different views of government finance were already taking hold.9 Thomas Edison supported Ford’s plan in an interview with the New York Times:

“But would not Mr. Ford’s suggestion that Muscle Shoals be financed by a currency issue raise some objections?” Mr. Edison was asked.

“Certainly. There is a complete set of misleading slogans kept on hand for just such outbreaks of common sense among people. The people are so ignorant of what they think are the intricasies [sic] of the money system that they are easily impressed by big words. There would be new shrieks of ‘fiat money,’ and ‘paper money’ and ‘green-backism,’ and all the rest of it—the same old cries with which the people have been shouted down from the beginning.”10

He explained that so long as the money created to finance government spending increases productive capacity, it will remain sound:

Don’t allow them to confuse you with the cry of “paper money.” The danger of paper money is precisely the danger of gold—if you get too much it is no good. They say we have all the gold of the world now. Well, what good does it do us? When America gets all the chips in a game, the game stops. We would be better off if we had less gold. Indeed, we are trying to get rid of our gold to start something going. But the trade machine is at present jammed. Too much paper money operates the same way. There is just one rule for money, and that is, to have enough to carry all the legitimate trade that is waiting to move. Too little or too much are both bad. But enough to move trade, enough to prevent stagnation on the one hand and not enough to permit speculation on the other hand, is the proper ratio.

In that remarkable statement, Edison dealt with money from both the domestic and the external perspectives. Domestically, we need enough money, including paper money to “carry all the legitimate trade that is waiting to move”—that is, to ensure effective demand is consistent with productive capacity. Given that much of the world was on a gold standard at the time, American exports relied on the rest of the world having sufficient “chips” to carry on international trade. Edison suggested a solution to increase both the domestic and foreign supplies:

How can the system be improved or changed? It can come about in several ways. One way would be to produce so much gold that its psychological hold would be broken. If we all had mines in our back yards or if synthetic gold could be made and sold 10 cents a pound, you would soon see gold disappear as the basis for money.

In that case people could no longer have confidence in it. Money ought to be plentiful and gold is not plentiful. It would be plentiful if it were mined in as large quantities as it could be, but an artificial scarcity is maintained by those who use gold to monopolize money. That is one way to do it—make it so plentiful that it drowns its fictitious value and drowns the superstition of the people along with it.

He endorses an alternative, “the method my friend Ford proposed the other day,” to simply “go along and forget about gold.” By abandoning the gold standard money could be, as it should be, plentiful. But wouldn’t that be inflationary—forgetting gold and letting government simply print money to finance its spending? Edison responded:

Now, here is Ford proposing to finance Muscle Shoals by an issue of currency. Very well, let us suppose for a moment that Congress follows his proposal. Personally, I don’t think Congress has imagination enough to do it, but let us suppose that it does. The required sum is authorized—say 30 million dollars. The bills are issued directly by the Government, as all money ought to be. When the workmen are paid off, they receive these United States bills. When the material is bought it is paid in these United States bills. . . . They will be based on the public wealth already in Muscle Shoals, and their circulation will increase that public wealth, not only the public money but the public wealth—real wealth.

When these bills have answered the purpose of building and completing Muscle Shoals, they will be retired by the earnings of the power dam. That is, the people of the United States will have all that they put into Muscle Shoals and all that they can take out for centuries—the endless wealth-making water power of that great Tennessee River—with no tax and no increase of the national debt.

The American colonists understood that so long as money is redeemed, there’s no inflation threat. In the Muscle Shoals case, the redemption would take the form of payment for the electricity produced rather than through taxation—but the outcome is the same as the currency is removed from circulation.”

14 Ingelesez: “The Great Depression, Roosevelt’s New Deal, and most importantly World War II led to an embrace of the Ford-Edison approach to government finance. The New Dealer chairman of the New York Fed, Beardsley Ruml, took a position like that taken by early colonial governors, titling an essay “Taxes for Revenue Are Obsolete.” He lists several reasons for taxes, arguing that “the war has taught the government, and the government has taught the people, that taxes have much to do with inflation and deflation,” but the “public purpose which is served should never be obscured in a tax program under the mask of raising revenue.” Taxes are not for revenue but to redeem the currency—to take it out of circulation where it might generate inflation.

That view was also adopted in Abba Lerner’s “functional finance approach”: government should spend more if there is unemployment; it should tax more only if there is inflation. A similar view was even expressed by Milton Friedman in his important 1948 policy proposal that all government spending should be financed by “printing money,” with the tax rate set so that all the money created over the course of a year would be removed through a balanced budget at full employment.11 (A surplus would drain more money out when beyond full employment—reducing the outstanding money supply, while a deficit below full employment would lead to a net increase of money.) By the late 1940s, these views were relatively noncontroversial: not only is a deficit called for when the economy operates with slack, but there is nothing wrong with financing budgets by issuing government money.

Close analysis of actual operations involved in spending by government shows that, despite the greater complexity, the logic of the process has not changed since colonial times. Tax payments require the simultaneous debit of the taxpayer’s deposit account and a debiting of reserves of the taxpayer’s bank. Government spending credits the recipient’s bank deposit and the bank’s reserves. Logic tells us that a deposit or reserve account cannot be debited unless it has previously been credited—a logic we already encountered in the discussion of colonial paper notes: government spends currency first and then receives it in taxes.12 More generally, as explored earlier, spending comes before income that can be taxed (or, as it is put in Keynesian macroeconomics textbooks, injections come before leakages).

What about bond sales? Doesn’t the government borrow if its spending exceeds tax revenue? Bond sales have an impact similar to taxes on private deposits and bank reserves: the buyer’s bank deposit and the bank’s reserves are debited. (If bonds are sold directly to banks, their reserves are debited.) Logic implies that there must be deposits and reserves to debit before bonds can be sold. Symmetry requires that government would lend deposits or reserves so that bonds could be purchased—and that could indeed be done (Grubb notes that early colonial governments did lend their notes and bills, and the Fed lends reserves to banks).

Alternatively, bonds could be sold to recipients of government spending. In that case, recipients would hold bonds rather than deposits after the government had spent. Or the bonds could be sold directly to banks, in which case they would hold bonds instead of reserves. This would commit government to paying interest if it sold bonds, rather than using taxes to withdraw deposits and reserves. From the private sector’s point of view, it is far better for the government to spend, rather than to lend, to generate the deposits and/or reserves that are debited when the government sells bonds. That way the private sector doesn’t have to go into debt to purchase the bonds.

We can think of injections of currency and reserves as deriving largely from government spending (channeled through its central bank); withdrawals come largely from tax payments. If government spending usually exceeds taxes, however, the injections exceed the leakages—leaving currency and reserves in the system. This is the main source of net financial wealth for the domestic private sector. (Liabilities issued by private sector entities to other private sector entities net to zero at the aggregate level.13) The Treasury can also sell its bonds, draining reserves from the system. We assign such operations to fiscal policy. Note that when the Treasury exchanges its bonds for reserves, this doesn’t directly affect the net financial wealth of the private sector—it is simply a portfolio substitution. Yet bonds imply future interest payments and so will increase private financial wealth over time.

The central bank can also inject and drain currency and reserves through actions taken for its own account. We call these monetary policy operations. When the Fed sells bonds the impact on the private sector is the same as a sale of bonds by the Treasury—reserves are drained—but we categorize the first as monetary policy and the second as a fiscal operation (“financing the deficit”), even though they are functionally equivalent. And in both cases, reserves must be in the banking system before they can be debited to “pay for” the bonds. Also note that if the government has spent more than its tax receipts (running a deficit), reserves will be injected into the banking system, ready for draining by either a monetary policy operation or a “borrowing” operation by the Treasury.14 Alternatively, reserves can be left in the system where they will earn the support rate paid on reserves set by the central bank.

To summarize, bond sales by either the central bank or the Treasury serve the functional purposes of removing reserves from the banks and offering a higher-interest-earning alternative to the central bank’s support rate. If, however, the central bank wants to push interest earnings down toward the support rate, it can engage in open market purchases—taking the bonds out of the system (à la “quantitative easing”).”

15 Ingelesez: “The New York Fed’s paper, cited above, nicely summarizes the mainstream view on the relation between savings and lending both nationally and internationally:

As an accounting matter, a country’s income is allocated to either consumption or saving while spending goes to either consumption or investment to replace or expand the capital stock. These two identities mean that a nation’s saving equals its investment spending when income equals spending. Opening up to the rest of the world through trade allows a country to have its income exceed its spending when its exports exceed its imports and this difference exactly equals the difference between gross saving and investment spending. Indeed, the gaps between spending and income, between saving and investment spending, and between exports and imports all equal a nation’s lending to (or borrowing from) the rest of the world.15

As we discussed earlier with regard to sectoral balances, if the U.S. government runs a deficit, the private sector runs a surplus (ignoring for a moment the possibility of a current account surplus). That private surplus will take the form of net financial claims on the government, in some combination of currency, reserves, and government bonds. As the causation goes from spending to income (injections to leakages), we can assign to the government’s budget deficit the causal role in generating the private sector’s surplus of income over its spending—what is commonly called saving. The government’s deficit finances the private sector’s saving. Households and nonfinancial firms will hold the generated surplus in the form of a combination of net claims on the financial sector and the government (bonds and cash), while banks will accumulate some combination of reserves and bonds that will equal the government’s deficit over the period.

Note that the “first step” of the private sector’s saving decision depends on its income, including that generated by net government spending. The “second step” involves the decision over how to hold the saving. It is the second decision that goes into the determination of what ends up in private portfolios, including government bonds. The impact of this second decision is on market interest rates that can trigger monetary policy actions, including open market sales or purchases of bonds.

This logic can be applied to the external sector. Spending injections of dollars into the global economy come from the United States through its purchases of foreign goods, services, and assets.16 The rest of the world can use dollar income to purchase U.S. goods and services,17 or the dollars can be accumulated as financial wealth. Idle dollar balances can be converted to U.S. Treasuries to increase earnings. The first step in the foreign saving decision depends, again, on income, which is partly determined by a country’s current account position with the United States. Given that many countries around the world formulate policies designed to promote trade surpluses, national incomes are boosted by current account outcomes generating positive saving by private sectors (and in some cases even by the government sectors). The second step determines how to hold the savings. In the first instance, a current account surplus will lead to an accumulation of dollar claims on the U.S. financial system; these will often be cleared, resulting in credits to central bank reserves held at the Fed. Portfolios are then reallocated to U.S. Treasuries to increase interest earnings.

Of course, a current account surplus country does not have to retain dollar assets in its portfolio. Holders of dollar claims will take a number of factors into consideration: U.S. interest rates relative to rates offered elsewhere, current and expected future exchange rates, the political and economic stability of the United States relative to alternatives, and so on. If such factors render dollar assets less desirable, there could be impacts on the dollar exchange rate, and it is conceivable that U.S. monetary policy might react by raising the rate target. The important point to understand, however, is that the exchange rate and interest rate effects arise in the second step of the saving decision, not in the first—that is, through the portfolio allocation strategy, not the creation of dollars. The United States is the source of the dollars moving through portfolios. We can think of foreign purchases of U.S. Treasuries as the redemption stage that follows the creation of dollars by U.S. purchases of output (or assets) from the rest of the world.

There is no question about a sovereign government’s ability to spend, about its “solvency,” or the “sustainability” of budget deficits or the possibility of its “bankruptcy.” A sovereign government is not like a firm or household. It can buy anything for sale in its own currency. It can never run out of its own “money”—its own IOUs—and can always create more by crediting bank accounts. It can never be forced to default on commitments in its currency, and it can never be forced into bankruptcy court. So what matters is not the “impact on the budget” but rather the impact of its spending on the economy.

What these considerations mean is that there is no danger that the U.S. government might run out of the dollars it uses to finance its spending.18 Likewise, there is no danger that the U.S. can run out of the dollars it uses to finance its imports. The government and import spending are financed by the creation of dollars simultaneously with the spending. In both cases, creation takes the form of credits to balance sheets that are offset by debits to balance sheets (double-entry bookkeeping, which has been around for half a millennium, ensures the credits equal the debits).19

Dollar finance cannot constrain U.S. government spending—which is determined in the budgeting process. Once approved, spending can take place up to the budgeted amount with the Fed, Treasury, and private banks cooperating to ensure the operations run smoothly. Similarly, dollar finance by foreigners cannot constrain spending by either the U.S. government (on domestic output or imports) or by the domestic private sector (on imports). U.S. government spending is the source of the dollars that can be used to buy Treasury bonds domestically, and U.S. spending on imports is the source of the dollars that can be used to buy and hold Treasury bonds abroad.

Excess savings do not slosh around the global economy providing the means by which profligate Americans can engage in excessive spending. Rather, the global savings are created by the “profligate” spending of Americans. Many nations pursue a strategy of depressing domestic living standards in order to increase export output, often with the purpose of obtaining dollar-denominated assets. The Asian Tiger crisis taught the world that maintaining pegged exchange rates is fraught with danger unless huge sums of dollar reserves are accumulated. Global savers also want to diversify into the currency issued by the largest open economy on earth. While it is likely that China will soon displace the United States as the world’s biggest economy, there are many reasons why renminbi assets will not challenge dollar assets for decades to come. (China is currently a net exporter; its capital markets are not sufficiently opened; and its policies and legal structures are not considered to be sufficiently transparent and predictable.) Euro assets, meanwhile, are diverse, and most are too risky—the most desirable (German) are scarce, and the most available (Italian) are scary. As already discussed, Japanese sovereign debt is hard to obtain (yen must be borrowed, not earned). The dollar will not always reign supreme, but it has a lot of life remaining as the most desirable asset to hold in portfolios.

And remember that this is the second step of the saving decision—the purchase of dollar assets is not a source of finance but rather represents a portfolio decision. It is the portfolio decision stage that takes into consideration interest rates and exchange rates, and these decisions, in turn, affect interest rates and exchange rates—though base dollar interest rates are determined by the Fed. Budget deficits and trade deficits affect the target rate only to the extent that the Fed reacts to them. Other rates are determined by other, more complex factors and can be affected by portfolio decisions, but they are not directly determined by the quantity of domestic or foreign saving.”

16 Ingelesez: “Finance is not a scarce resource to be allocated among alternative forms of spending. We can have as much as we want. Indeed, we have far more than we need. The problem in the run-up to the global financial crisis was not excess global savings but rather a runaway financial system that was engaging in imprudent and fraudulent activities, as well as some borrowers who took on too much debt that was pushed in their direction. The solution is to reign in finance, not to reduce aggregate demand through fiscal austerity. The time for constraining aggregate demand will be when we face shortages of real resources (domestic resources plus those we can import), which would threaten to bring on general and sustained inflation.

Government policy should therefore be redirected to reduce inequality and to promote productive activity. Our financial sector has grown too large—as indicated by its share of corporate profits—and far too much capital is being directed toward financial assets or financialized assets (including housing and commodities). Over the past half century, our economy has increasingly relied on serial asset bubbles to boost the holdings of wealthy savers, while our productive sectors have lost ground to competitors. Stagnant or even falling incomes for the bottom quintiles promote sales of cheap imports. Foreign competition as well as depressed domestic wages reduce the incentives to innovate and invest in labor-saving capital. Corporate profits are used to inflate bubbles rather than to increase capacity.

While the United States cannot run out of dollars to finance the “twin deficits,” this does not mean we should be complacent. Rather than focusing on the twin deficits themselves, we should be focused on promoting investments in human, private, and public capital. The problem with America’s twin deficits is not that they expose us to bankruptcy, but that the twin deficits could be symptoms of underlying structural problems that need to be addressed directly. What Edison noted a century ago holds true today: people’s instincts tell them that “something is wrong” and “the wrong somehow centers in money.” Maybe the “dynamite” we need is a sound understanding of financial balances and sovereign currency.”

Notes

The author thanks Yeva Nersisyan and Scott Fullwiler for their assistance with the data discussed in this article.

1 David P. Goldman, “A Path Out of the Trade and Savings Trap,” American Affairs 1, no. 3 (Fall 2017): 31–44.

2 Thomas Klitgaard and Linda Wang, “Is the United States Relying on Foreign Investors to Fund Its Larger Budget Deficit?,” Liberty Street Economics, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, November 28, 2018.

3 To put it simply, duration has to do with the time to maturity. Keynes had discussed a similar concept he called the “square rule”—noting that potential capital losses on longer maturity bonds are increasingly likely to wipe out interest earnings as the interest rate rises.

4 Paul Sheard, “Repeat After Me: Banks Cannot And Do Not ‘Lend Out’ Reserves,” Standard & Poors Credit Market Services, Global Economics and Research, August 13, 2013.

5 James K. Galbraith, foreword to Seven Deadly Frauds of Economic Policy by Warren Mosler, (Valance Company, 2010), 2.

6 Some were also “redeemable” or convertible to precious metal or other currencies—although many or most were not. And it is sadly true that some governments abused the privilege—issued too much currency, or “cried down” its value (announced that outstanding currency would henceforth be accepted in payment at a lower nominal value), or even refused to accept its own currency in payment (effectively a default). There are many sorry tales that one could tell when it comes to monetary history—both of failures of private monies as well as of public monies. The Bank of England got its start when the King defaulted on his tally sticks, refusing to accept them in payment to the Crown, and according to some reports, Zimbabwe’s government today is refusing to accept its own coins in payment.

7 See Farley Grubb, “Colonial Virginia’s Paper Money Regime, 1755–1774: A Forensic Accounting Reconstruction of the Data,” Historical Methods 50, no. 2 (2017): 96–112; and Cory Cutsail and Farley Grubb, “The Paper Money of Colonial North Carolina, 1712–1774,” Working Paper No. 2017-01, Alfred Lerner College of Business and Economics, University of Delaware, 1971. Quotes here are from the second paper.

8 Sometimes provisions were made in which some notes were not burned but were retained for specific uses. Importantly, however, the idea was not to re-spend them.

9 In the UK, these views were called the “Treasury View.”

10 See Serban V. C. Enache, “Thomas Edison and Henry Ford Explain Modern Monetary Theory in 1921,” Hereticus Economicus, April 23, 2018.

11 See L. Randall Wray, “A Monetary and Fiscal Framework for Economic Stability: A Friedmanian Approach to Restoring Growth,” September 1, 2002.

12 Note that this sequence is indicated by our term “tax return” (and the word “revenue” itself is derived from the Latin for “come back” (revenire) which became revenue in French and then in late Middle English. What “comes back”? The currency is returned to the sovereign that issued it.

13 The domestic private sector can also have net financial assets in the form of claims on the rest of the world.

14 The Treasury, Fed, and special banks cooperate using complex procedures and tax and loan accounts to ensure Treasury checks never bounce.

15 Klitgaard and Wang.

16 Plus remittances, foreign aid, and factor payments to foreigners.

17 Plus factor payments to the United States, and foreign aid and remittances to the United States (if any).

18 In March 2005, in response to a question by Rep. Paul Ryan (“Do you believe that personal retirement accounts can help us achieve solvency for the system [Social Security] and make those future retiree benefits more secure?”), Chairman Greenspan said: “Well I wouldn’t say that the pay-as-you-go benefits are insecure, in the sense that there’s nothing to prevent the federal government from creating as much money as it wants and paying it to somebody.” Later, in a 60 Minutes interview by Scott Pelley, Chairman Bernanke said much the same thing. When asked about the Fed’s bailout of Wall Street, Pelley asked “Is that tax money that the Fed is spending?” Bernanke (correctly) responded: “It’s not tax money. The banks have—accounts with the Fed, much the same way that you have an account in a commercial bank. So, to lend to a bank we simply use the computer to mark up the size of the account that they have with the Fed.” That is true, and it applies equally well to Fed purchases of assets (Fed “lending” is really just the purchase of a bank’s IOU). In truth, both Bernanke and Greenspan have accurately described the way both the Fed and the Treasury spend—they credit bank accounts.

19 When financial institutions are involved, we actually use quadruple entry booking since payments are made and received through banks so there are entries on their balance sheets too.