T. Fazi eta B. Mithell-en Why the Left Should Embrace Brexit

(https://www.jacobinmag.com/2018/04/brexit-labour-party-socialist-left-corbyn)

Remainers claim that Brexit will be an economic apocalypse. But it provides the opportunity for a radical break with neoliberalism.

(i) Ezkerra (galduta) eta Brexit: histeria besterik ez1

(ii) Distopiaren modelatzea2

(a) Modelo neoliberalak, merkatu libreak3

(b) Brexit eta apokalipsia4

(c) Botoak Brexit-en alde, ekonomialariak erabat galduta5

Source: Office of National Statistics and authors’ calculations.

(d) Langabezia6

(e) Industriaren datuak7

(f) Libraren porrotaz8

(iii) Merkatu bakarraz, esandakoa eta datuak9

Source: Centre for Business Research, University of Cambridge.

(a) Hazkunde ekonomikoa10

Source: US Conference Board, Total Economy Database.

(b) Esportazioak11

Source: IMF Directions of Trade Statistics.

The same applies to the share of UK exports to the EU and EMU, which has stagnated since the creation of the Single Market and has been in decline since the early 2000s (returning to the level of the mid-1970s), with non-EU export markets growing much faster than those within the EU and the eurozone.

Source: IMF Direction of Trade Statistics and authors’ calculations.

(c) Abantailarik ez EBn egonez12

(iv) Ezkerra eta merkatuaren liberazioa13

(v) Ezkerra eta Brexit14

1 Ingelesez: “Nothing better reflects the muddled thinking of the mainstream European left than its stance on Brexit. Each week seems to produce a new chapter for the Brexit scare story: withdrawing from the EU will be an economic disaster for the UK; tens of thousands of jobs will be lost; human rights will be eviscerated; the principles of fair trials, free speech, and decent labor standards will all be compromised. In short, Brexit will transform Britain into a dystopia, a failed state — or worse, an international pariah — cut off from the civilized world. Against this backdrop it’s easy to see why Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn is often criticized for his unwillingness to adopt a pro-Remain agenda.

The Left’s anti-Brexit hysteria, however, is based on a mixture of bad economics, flawed understanding of the European Union, and lack of political imagination. Not only is there no reason to believe that Brexit would be an economic apocalypse; more importantly, abandoning the EU provides the British left — and the European left more generally — with a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to show that a radical break with neoliberalism, and with the institutions that support it, is possible.”

2 Ingelesez: “Modelling Dystopia

(Dystopia: an imaginary place where everything is as bad as it can be)

To understand why the anti-Brexit stance of most European progressives is unfounded and actually harmful, we should start by looking at the most pervasive Brexit-related myth of all: the idea that it will lead to an economic apocalypse. For many critics this is an open-and-shut case, proven simply by citing a much-publicized leaked report prepared by the British government’s own Department for Exiting the European Union (DExEU). The document concludes that all possible forms of Brexit, from remaining in the Single Market to a free-trade deal or no deal at all, would have a substantially negative impact on the UK’s GDP. Estimates range from a 2 percent lower GDP and 700,000 fewer jobs over the next fifteen years to an 8 percent lower GDP and as much as 2.8 million fewer jobs.

This line of argument can be found in a recent article by anti-Brexit commentator Will Denayer, which cites the fact that the report was produced by Britain’s “pro-Brexit government” as proof of its reliability. However, he fails to acknowledge that these forecasts suffer from a neoliberal bias embedded within the forecasting models themselves. The mathematical models used by the British government are highly complex and abstract, and their results are sensitive to the numerical calibration of the relationships in the models and the assumptions made about, for example, the effects of technology. The models are notoriously unreliable and easily manipulated to achieve whatever outcome one desires. The British government has refused to release the technical aspects of their modeling, which suggests they do not want independent analysts examining their “black box” assumptions.”

3 Ingelesez: “The neoliberal biases built into these models include the assertion that markets are self-regulating and capable of delivering optimal outcomes so long as they are unhindered by government intervention; that “free trade” is unambiguously positive; that governments are financially constrained; that supply-side factors are much more important than demand-side ones; and that individuals base their decision on “rational expectations” about economic variables, among others. Many of the key assumptions used to construct these exercises bear no relation to reality. Simply put, the forecasting models — much like mainstream macroeconomics in general — are built on a sequence of interrelated myths. Paul Romer, who earned his PhD in economics in the 1980s at the University of Chicago, the temple of neoliberal economics, recently provided a scathing attack of his own profession in a paper titled “The Trouble With Macroeconomics.” Romer describes the standard modelling approaches used by mainstream economists — which he calls “post-real” — as the end point of a three-decade intellectual regression.”

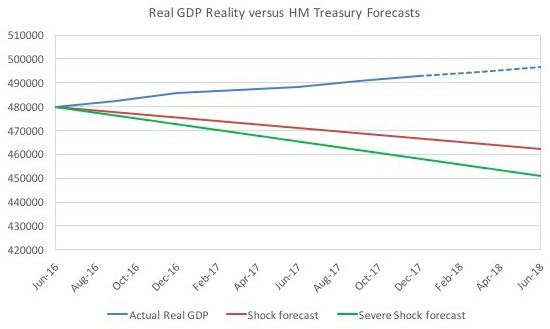

4 Ingelesez: “It is no surprise, then, that these models utterly failed to predict the financial crisis and Great Recession, and continuously fail today to produce reliable forecasts about anything. Brexit is an obvious example. In the months leading up to the referendum, the world was flooded with warnings — from the IMF, the OECD, and other bastions of contemporary economics — claiming that a Leave vote in the referendum would have immediate apocalyptic consequences for the UK, causing a financial meltdown and plunging the country into a deep recession. The most embarrassing forecast on “the immediate economic impact of a vote to leave the EU on the UK” was published by the Tory government. The aim of the “study” in question, released in May 2016 by the UK Treasury, was to quantify “the impact … over the immediate period of two years following a vote to leave.”

Within two years of a Leave vote, the Treasury predicted that GDP would be between 3.6 and 6 percent lower and the number of people unemployed would rise by as much as 820,000. The predictions in the May 2016 “study” sounded dire, and were clearly aimed at having the maximum impact on the vote, which would be held a month later. Just weeks before the referendum, the then-chancellor George Osborne cited the report to warn that “a vote to leave would represent an immediate and profound shock to our economy” and that “the shock would push our economy into recession and lead to an increase in unemployment of around 500,000.”

5 Ingelesez: “Nonetheless, the majority of voters opted for Brexit. In doing so, they proved economists wrong once again, since none of the catastrophic scenarios predicted in the run-up to the referendum have occurred. As Larry Elliott, Guardian economics editor, wrote: “Brexit Armageddon was a terrifying vision — but it simply hasn’t happened.” With almost two years having passed since the referendum, the economic data coming out of the UK makes a mockery of those doom-laden warnings — and of the aforementioned government report in particular. Data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS), shows that by the end of 2017, British GDP was already higher by 3.2 percent relative to its level at the time of the Brexit vote — a far cry from the deep recession we were told to expect.”

6 Ingelesez: “Meanwhile, the unemployment rate dropped from 4.9 percent to 4.3 percent between June 2016 and January 2018, while the number of people unemployed fell by 187,000 — a forty-three-year low. Economically inactive people — those who are neither working nor looking for a job — fell by the largest amount in almost five-and-a-half years. So much for the countless workers that were supposed to be made unemployed as a result of the Leave vote.”

7 Ingelesez: “Particularly embarrassing for the professional doomsayers is the data on British industry over the past two years. Despite the uncertainty concerning the negotiations with the EU “manufacturing is seeing its strongest growth since the late 1990s,” according to the Economist as well as the British manufacturers’ association EEF. This is largely due to a growing demand for British exports, which are reaping the benefits of the lower pound and improved world trade conditions. According to a report by Heathrow Airport and the Centre for Economics and Business Research (CEBR), UK exports are at their strongest position since 2000. As the Economist recently put it: “Britain’s long-suffering makers are enjoying a once-in-a-generation boom,” as the shifts induced by Brexit engender a much-needed “rebalancing” from boom-and-bust financial services towards manufacturing. This is also spurring a growth in investment. Total investment spending in the UK — which includes both public and private investment — was the highest of any G7 country during 2017: 4 percent compared to the previous year.”

8 Ingelesez: “Predictions that a Leave victory would cause the British economy to be crushed by a “run on the pound” have proven equally unfounded: yes, sterling has indeed lost ground to other major currencies since the referendum, but not only has this not destroyed the British economy — quite the opposite, in fact, as we have seen — but its value has been on the rise again since early 2017.”

9 Ingelesez: “The Sainted Single Market

So, given the paucity of evidence for Brexit precipitating an economic collapse, what was behind the blind certainty of the commentariat? One important piece of ideology undergirding the whole Brexit debate is the notion that Britain enjoyed huge economic benefits from joining the EU (or EEC as it was known in 1973). Does that claim hold up to evidence? As a recent study by the Centre for Business Research (CBR) at Cambridge University shows (see graph below), “there was no improvement in UK growth in per capita after 1973 when compared with previous decades. Indeed, GDP per head clearly grew more slowly after accession than it had in pre accession decade.””

10 Ingelesez: “The researchers conclude that “there is no evidence that joining the EU improved the rate of economic growth in the UK.” The much-vaunted establishment of the Single Market in 1992 didn’t change things — neither for the UK nor for the EU as a whole. Even when we limit ourselves to evaluating the success of the Single Market on the basis of mainstream economic parameters — productivity and GDP per capita — there is very little to suggest that it has lived up to its proponents’ promises or to official forecasts. The following graph provides a long-term comparison between the EU 15 and the US in terms of GDP per hour worked (one measure of labor productivity) and GDP per capita.”

11 Ingelesez: “The data clearly shows that not only has the Single Market (starting at the green line) failed to improve the EU15 economies relative to the US, but would actually appear to have worsened it.

Even more interestingly, the creation of the Single Market has not even boosted trade within the EU. The following graph shows the percentage of exports between EU and EMU [European Monetary Union, developing into the eurozone] countries as a percentage of total EU and EMU exports. After experiencing a steady rise throughout the 1980s, this proportion effectively stagnated between the Single Market’s creation in the mid-1990s and the mid-2000s, and has been on a downward trend ever since (with a slight recovery post-2014). A Bruegel note adds that “the Euro Area has been following nearly the exact same pattern as the European Union as a whole, suggesting the common currency might not have had the expected effect on trade between Euro Area members.””

12 Ingelesez: “As the Cambridge researchers note, this suggests “a negligible advantage to the UK of being a member of the EU.” Moreover, it shows that Britain has been diversifying its exports for quite some time and is much less reliant on the EU today than it was twenty or thirty years ago. A further observation drawn from the IMF Directions of Trade database is that while global exports have grown fivefold since 1991 and advanced economies exports have grown by 3.91 times, EU and EMU exports have only grown by 3.7 and 3.4 times respectively.

These results are consistent with other studies that show that tariff liberalization in itself does not promote growth or even trade. In fact, the opposite is often true: as Cambridge economist Ha-Joon Chang has shown, all of today’s rich countries developed their economies through protectionist measures. This casts serious doubts over the widespread claim that leaving the Single Market would necessarily mean “lower productivity and lower living standards.” It also exposes as utterly “implausible,” in the words of the Cambridge researchers, the Treasury’s claim that Britain has experienced a 76 percent increase in trade due to EU membership, which could be reversed upon leaving the EU. The Cambridge economists conclude that average tariffs are already so low for non-EU nations seeking to trade within the EU that even in the case of a “hard Brexit” trade losses are likely to be limited and temporary.”

13 Ingelesez: “The Left and Liberalization

This makes even more ridiculous the contemporary left’s support for “free trade.” We should wince at the thought of what future historians will think of such aberrations as the Labour Campaign for the Single Market, or its allies Yanis Varoufakis and his DiEM25 group. Especially if we consider that even mainstream economists such as Dani Rodrik are now explicitly saying that trade liberalization “is causing more problems than it solves,” is one of the root causes of the anti-establishment backlash engulfing the West, and that the time has come to “plac[e] some sand in the wheels of globalization.” In this sense, one would expect the Left to see Brexit as the perfect opportunity to “rewrite [the] multilateral rules,” as Rodrik counsels — not to cling tooth and nail to a failing system.

Furthermore, it is often forgotten in the debate over Brexit that the Single Market is about much more than just trade liberalization. A crucial tenet of the Single Market was the deregulation of financial markets and the abolition of capital controls, not only among EU members but also between EU members and other countries. As we argue in our recent book, Reclaiming the State, this reflected the new consensus that set in, even among the Left, throughout the 1970s and 1980. This consensus held that economic and financial internationalization — what today we call “globalization” — had rendered the state increasingly powerless vis-à-vis “the forces of the market.” In this reading, countries therefore had little choice but to abandon national economic strategies and all the traditional instruments of intervention in the economy, and hope, at best, for transnational or supranational forms of economic governance.

This resulted in a gradual depoliticization of economic policy, which has been an essential element of the neoliberal project, aimed at insulating macroeconomic policies from popular contestation and removing any obstacles put in the way of capital flows. The Single Market played a crucial role in the neoliberalization of Europe, paving the way for the Maastricht Treaty, which embedded neoliberalism into the very fabric of the European Union. In doing so it established a de facto supranational constitutional order which no individual government has the power to change. In this sense, it is impossible to separate the Single Market from all the other negative aspects of the European Union. The EU is structurally neoliberal, undemocratic, and neocolonial in nature. It is politically dominated by its largest member and the policies it has driven have had disastrous social and economic effects.”

14 Ingelesez: “So why does the mainstream left have such a hard time coming to terms with Brexit? The reasons, as we have noted, are numerous and often overlapping: the Left’s fallacious belief that “openness” and trade bring prosperity; its internalization of mainstream economic myths, particularly concerning public deficits and debts; its failure to understand the true nature of the Single Market and of the European Union in general; the illusion that the EU can be “democratized” and reformed in a progressive direction; the flawed notion that national sovereignty has become irrelevant in today’s increasingly complex and interdependent international economy, and that the only hope of achieving any meaningful change is for countries to “pool” their sovereignty together and transfer it to supranational institutions.

One important reason for the Left’s embrace of anti-Brexit panic has been the welcome distraction this offers from dealing with a more substantial problem: that the economic system underpinning the West in general is in serious decline. Another study by the aforementioned CBR at Cambridge University found that the impact of Brexit is likely to be much more mild than government forecasts “even if the UK ends up with no free trade agreement or other privileged access to the EU single market” — that is, even in the event of a so-called “hard Brexit.” Overall, the Cambridge researchers found:

The economic outlook is grey rather than black, but this would, in our view, have been the case with or without Brexit. The deeper reality is the continuation of slow growth in output and productivity that have marked the UK and other western economies since the banking crisis. Slow growth of bank credit in a context of already high debt levels, and exacerbated by public-sector austerity prevent aggregate demand growing at much more than a snail’s pace.

In other words, to the extent that the UK continues to face serious economic problems — suppressed domestic demand, ballooning private debt, decaying infrastructure, and deindustrialization — these have nothing to do with Brexit, but are instead the result of the neoliberal economic policies pursued by successive British governments in recent decades, including the current Conservative government.”

joseba says:

joseba, 2018/05/20 06:27 zera dio:

Bill Mitchell-en The Europhile Left loses the plot

(http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=39212)

Regular readers will know that I have delved into social psychology in the last decade or so as a way of educating myself on why ideas survive when their logical consistency is lacking and their empirical content is zero. I have gained a good understanding of this phenomenon by exploring the literature on patterned group behaviour and the work by Irving Janis in the early 1970s on Groupthink. While I usually demonstrate instances of this destructive group behaviour on the part of the Right, it is also clear that that the Europhile Left is riddled with the problem. To the point of not even valuing debate anymore. At the weekend (April 29, 2018), the excellent Jacobin magazine published an Op Ed piece by myself and Thomas Fazi – Why the Left Should Embrace Brexit – which considered the Brexit issue and provided an up-to-date (with the data) case against the on-going hysteria that Britain is about to fall off some massive cliff as a result of its democratically-arrived at decision to exit the neoliberal contrivance that the European Union has become. The article was rather moderate in fact and considered the on-going failure of the apocalyptic arguments that have been introduced against Brexit, both before and after the Referendum. But the social media response (negative) has been at elevated levels of hysteria. Inane claims. Groupthink in action. And it is why the progressive cause is such a push over by the organised Right.

I hinted at our Jacobin argument in this recent blog post – The facts suggest Britain is not as reliant on EU as the Remain camp claim (April 16, 2018) – and if you want some facts that blog post has them as does the Jacobin article, which built on the blog post. The facts are presented at a reasoned level of detail.

The social media response to the Jacobin article has been beyond amazing. Remember this is magazine (and its on-line counterpart) describes itself as (Source):

… a leading voice of the American left, offering socialist perspectives on politics, economics, and culture.

It is not likely that right-wingers (at least in one meaning of that term) would read Jacobin.

It is apparent from the response that there is, what I would call a ‘right-wing’ element on the Left though – in the sense that many commentators on the article – struggling to offer just a few words within the limits of their hysteria – have recommended Jacobin editors “delete” the article (‘burn the books’) or accused the editors of being “asleep” when they published our work.

One character wrote on Jacobin’s Facebook page that our article was “inchoate drivel” with no further input. He obviously had his English dictionary open next to him and wanted us to be impressed by his appearance of being very literate.

Another commentator said that he could “guarantee the authors of this are american”, while another said we obviously didn’t care about jobs (“The far left Lexiters care little about jobs”), obviously not aware of any of my work over the last 30 or more years.

Another dismissed the article as “clickbait for the progressively minded”. Nothing further added. Good work there.

Someone else opined that “This really is too silly. Were the jacobin grownups asleep when this was published?”, while another enquired about the health of Jacobin (“are u ok?”).

Another said it was just a case of the “The idiot left strikes again” – strong argument that. Another just wanted the Nazi option, “Delete this” – a modern version of ‘burn the books’.

Some social media expert invoked a deity “Oh god – I may need to “unfollow” Jacobin” – which probably wouldn’t bother them one bit. The IQ of its readership would increase.

Someone else said we were just providing “fuel for nationalists” as if the EU and the Eurozone hasn’t already done that.

Some other commentator, clearly totally on top of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) not!, tried to be funny by claiming that we would be supporting “Calexit” (California leaving the US).

And so as to demonstrate that they can engage with sophisticated argument, another commentator provided the following comment – “what bullshit”. That depth of engagement probably required all of the intellectual facilities that were available to that person.

I stopped reading the feedback given the level of sophistication was above what my pitiful, Brexit-supporting brain could reasonably be expected to comprehend.

I am glad I decline to have a Facebook account. The Twitter responses were also hysterical.

This prompted the European editor of Jacobin, who did a lot of great editorial work on our article (Thanks to him for a very professional job) issuing the following Tweet (April 29, 2018):

Yes it is bizarre that the anti-Brexit Left do not even want a debate. They just called on Jacobin editors to “delete it”. Why? Because evidence and well-argued points challenge their Pro-European hysteria.

And the nonsense reached a very moral low-point where honesty disappeared and meagre venal bile ruled when a commentator accused us of “siding with … [the] … murderer” of British Labour MP Jo Cox.

The European Editor of Jacobin @ronanburtenshaw has provided a solid wall against this bile today.

Here is a snippet from his Twitter account. Plaudits to him!

And:

While my 2015 book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale – accused the Right of being trapped in Groupthink, a concept that was introduced into the literature by the work of Irving Janis in 1972, the hysteria displayed in the last few days by the ‘Left’ is symptomatic of a group that is captured in this same destructive dynamic.

The original reference by the way is Irving L. Janis, Victims of Groupthink (New York: Houghton Mifflin).

Irving Janis identified communities of scholars working within a dominant culture, which provides its members which a sense of belonging and joint purpose but also renders them oblivious and hostile to new and superior ways of thinking.

The ‘communities’ do not have to be of ‘scholars’ or within the academy. All groups are susceptible to Groupthink were their decision-making deteriorates due to what Irving Janis said was the force of “group pressure” leading a decline in “mental efficiency, reality testing, and moral judgment”.

Irving Janis wrote:

I use the term groupthink as a quick and easy way to refer to the mode of thinking that persons engage in when concurrence-seeking becomes so dominant in a cohesive ingroup that it tends to override realistic appraisal of alternative courses of action …

requires each member to avoid raising controversial issues …

Note, this patterned behaviour “tends to override realistic appraisal of alternative courses of action”.

The group dynamics becomes a sort of ‘mob-rule’ that maintains discipline within paradigms. Conformity is required if one wishes to remain within the group and benefit from it personally.

Applying that sort of ‘mob-rule’ behaviour to the social media response to our Jacobin article would give a high concordance.

As would an application of the eight “symptoms” that Irving Janis says define Groupthink:

1. An illusion of invulnerability.

2. A collective rationalisation.

3. The belief in inherent morality.

4. The capacity to hold stereotyped views of out-groups

5. Direct pressure on dissenters.

6. The capacity to self-censorship.

7. The illusion of unanimity.

8. Self-appointed mind guards.

Groupthink becomes apparent to the outside world when there is a crisis or in Janis’s words a ‘fiasco’.

The 8 symptoms are clearly identifiable in the way the Europhile Left tend to respond to any proposal that offers an alternative to their vision of a grand European democracy, delivering progressive outcomes to a fully-engaged (politically) citizenship.

If one dares mention Brexit, the sort of repulsion that the Jacobin article has generated follows quickly.

That is Groupthink. It is ugly. But it is, moreover, a sign that the ‘group’ has lost (or is losing) touch with the facts.

You get a sense how everything that is negative in the UK at present has a ‘Brexit’ label attached to it.

For example, on the jobs front, the House of Commons Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee released a report (March 1, 2018) – The impact of Brexit on the automotive sector 0 which the press called a “detailed inquiry into the UK’s car industry” (Source).

The Report is 36 pages long, which would hardly suggest a ‘detailed’ study of a very complex sector.

The local press (in the North East of England) reported the release of the study with dramatic headlines (March 1, 2018) – 7,000 Nissan workers could lose their jobs if Theresa May gets Brexit wrong and elaborated:

A detailed inquiry into the UK’s car industry has concluded it could be destroyed by a ‘no-deal’ Brexit … Even quitting the European Union with a trade deal in place can only hurt rather than help the automotive sector, which directly or indirectly employs 900,000 people across the UK.

The findings from the cross-party House of Commons Business Committee reveals the threat to 7,000 jobs at Nissan’s car plant in Sunderland, as well as thousands of others in the carmaker’s supply chain.

The article went on for several paragraphs with dire warnings about trade deals and quoted a Labour politician on the Committee as saying “There is no credible argument to suggest there are advantages to be gained from Brexit for the UK car industry”

I should add that the politician quoted – one Rachel Reeves – Labour member for Leeds West is an enthusiastic member of – Progress – which is the New Labour organisation established to support Tony Blair’s atrocious period as Labour leader and Prime Minister.

It pushes out a monthly magazine that is about as ‘progressive’ as you would expect from a ‘Genghis Khan Weekly’

She is also deeply opposed to Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership and made a large song and dance when refusing to serve on his front bench when he became leader on September 12, 2015.

As one commentator noted (humourously) – “not that she had been asked, which speaks volumes” (Source).

In 2015, as the “shadow work and pensions secretary” (before Corbyn was elected) she reflected on the role of the British Labour Party (Source):

We are not the party of people on benefits. We don’t want to be seen, and we’re not, the party to represent those who are out of work.

Understandably, this caused a furore.

Owen Jones tweeted in response (March 17, 2015) “So when I meet unemployed youngsters, I tell them Labour doesn’t want to represent them?”

She had previously said that “Labour would be tougher than the Conservatives when it came to cutting the benefits bill.”

Blairite … what would you expect.

She was also outed in 2017 for sending a “secret email to only some Leeds West members, asking them to support a move to rig the selection of delegates to Labour’s 2017 annual Conference – for the specific purpose of preventing future left-wing leadership candidates.” (Source)

And she is in the Remain camp and wrote (September 19, 2016) just after the Referendum vote about a visit to a worksite two days before the vote:

I knew in my heart at lunchtime on the day of that visit that we’d lost the referendum. My head had told me – the economist – that we would win because the consequences of leaving were a risk voters wouldn’t take. But, by Friday morning, we knew the Leave campaign’s emotional message was stronger than the rational arguments of the Remain campaign.

So the put down. Brexit was emotional not rational. The economic arguments put by the Remain camp were rational and sensible – that sort of line that the Remainers pump out.

Our Jacobin article tackled that question head on. The right-wing Left didn’t like it one bit.

But back to the House of Commons Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee Report which actually notes in “Chapter 6 Certainty and transition” that:

… the continuing uncertainty is affecting investment decisions, which will have a long-term impact on jobs in the sector … The drop in demand has contributed to the reduction of work in some plants, such as the Vauxhall plant at Ellesmere Port, and the JLR plant at Halewood, where Brexit uncertainty was cited by the company as a contributory factor.

But – back in the real world:

… it is in our view likely that sales have been more affected by the move against diesel vehicles on environmental grounds and the uncertainty around the pace of the transition to electric vehicles.

Why didn’t the press report on that. The article cited above didn’t mention the diesel issue which is killing the British car industry and reflects poor management decisions in the past.

The data is clear.

The UK organisation – Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) – obviously tailoring their name to benefit from the popularity of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) (American readers – this is a joke! within a joke!) released Car Registrations data for March 2018 – which I reproduce their summary table:

Diesel in in free fall due to environmental concerns and new environmental regulations (including taxes).

In terms of brands, Nissan was down 33.51 per cent in the year to March 2018 and Jaguar was down 29.98 per cent, and Land Rover was down 26.09 per cent.

The job losses that have started to occur as a result of the decline in diesel demand was clearly pointed out (to their credit) in the Financial Times stories – Nissan to lay off hundreds of workers from UK plant (April 20, 2018) and Jaguar Land Rover blames diesel slide for loss of 1,000 jobs (April 14, 2018).

The FT notes that “The UK’s car industry is heavily exposed to diesel technology, with more than 1m engines and 725,000 diesel cars made in Britain last year”.

A spokesperson for Nissan UK clearly noted that:

This is not related to Brexit. In time we expect volumes to increase as we prepare to launch the next generation Juke, Qashqai and X-Trail, all being built at NMUK.

None of the social media heroes attacking Jacobin and Thomas and I thought to address any of the issues raised.

They did not engage with our demonstrated point that the economic models that the British government and other institutions have used to generate dire Brexit meltdown scenarios are deeply flawed, embedded with neoliberal biases and so inaccurate that they are not worth considering.

None of them thought the unbelievable forecasting errors from the HM Treasury exercise in May 2016 (just before the Referendum), where they claimed that by now the UK would have a GDP between 3.6 and 6 percent lower and the number of people unemployed would rise by as much as 820,00 were an issue.

We also showed that the data from British industry over the past two years had generated the strongest growth since the late 1990 despite claims that the Brexit ‘uncertainty’ would see British output collapsing by now.

The social media heroes didn’t think it worth engaging with that reality. It would be too challenging for their case.

None of them addressed the detailed analysis we presented of Britain’s fortunes (or not) since the Single Market was introduced in 1992.

None of them responded to literature we cited which show that “here is no evidence that joining the EU improved the rate of economic growth in the UK”.

And so on.

Apparently, a right-wing corporatist system (the EU), which has deliberately created a situation where millions of people have lost their jobs and many are heading into poverty, which has wiped out the hard-earned savings of many families, which has denied hundreds of thousands of its youth a future, which has transferred billions of euros in the hands of the banksters at the expense of pensions, public services, wages growth, etc, is preferred by this lot.

And finally, the political vision that the social media heroes portray is so depressing that we might as well all give up.

In my original articles on Brexit – just before and after the Referendum (see below) – I noted that leaving the European Union might be a disaster for Britain, if the Tories use it to further their neoliberal agenda, not that membership of the EU stopped them in that regard.

But, significantly, I considered the victorious vote to Leave to be a crucial first step in reasserting a progressive political agenda for Britain free of the corporatist, neoliberal shackles that come with EU membership.

The challenge for British Labour was to grasp that ‘space’ and really distance itself from Blair’s horrible New Labour years and do something truly progressive.

The comments in recent days after our Jacobin article was published suggest that the British Left and its Europhile allies have no vision of a progressive future and no confidence that British Labour can deliver a significant change in the political narrative and outcomes.

That is depressing.

They would rather be cosseted in the right-wing corporatist system of the EU than take a chance on their own political future.

Meanwhile, they soothe themselves with nonsense about restoring democracy in Europe (and Britain) through grand pan-international arrangements that haven’t a hope in hell of delivering anything other than the occasional talkfest and tweets announcing that ‘reform’ is just around the corner.

Here are some of the many blog posts I have written about Brexit. The first two were written immmediately before and after the Referendum.

A well-known ‘progressive’ tweeted after my second post, in the immediate aftermath of the Leave victory, that I was delusional. That seems polite compared to what has transpired in the last few days after our Jacobin article was published.

1. Britain should exit the European Union (June 22, 2016).

2. Why the Leave victory is a great outcome (June 27, 2016).

3. Brexit signals that a new policy paradigm is required including re-nationalisation (July 13, 2016).

4. Mayday! Mayday! The skies were meant to fall in … what happened? (August 24, 2016).

5. Oh poor Britain – overrun by chlorinated chickens, hapless without the EU (February 1, 2018).

Conclusion

I think the response from Jacobin’s European editor is very telling.

The reactions to a fairly sober piece from us on why the claims about Brexit to date have been far fetched and why Reclaiming the State is a crucial element in a restatement of a progressive agenda for Britain and elsewhere are frankly unbelievable.

And they summarise in hundreds of limited character Tweets and short Facebook comments just how lost the Europhile Left has become.

joseba says:

Europako Ezkerra, Brexit eta ondorengoak

Bill Mitchell-en The Europhile Left use Jacobin response to strengthen our Brexit case

(http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=39412)

Regular readers will recall that Thomas Fazi and I published an article in the Jacobin magazine (April 29, 2018) – Why the Left Should Embrace Brexit – which considered the Brexit issue and provided an up-to-date (with the data) case against the on-going hysteria that Britain is about to fall off some massive cliff as a result of its democratically-arrived at decision to exit the neoliberal contrivance that the European Union has become. There was an hysterical response on social media to the article, which I considered in this blog post a few days later – The Europhile Left loses the plot (May 1, 2018). In recent days, two British-based academics have provided a more thoughtful response in the Jacobin magazine (May 18, 2018) – Caution on “Lexit”. Here is a response which was co-written with Thomas. As a general observation, I noted some prominent progressive voices citing their attack on us enthusiastically, one even suggesting it landed “some good punches” after taking “a while to warm up”. Well, I can assure Andrew that my face (nor Thomas’s) was the slightest bit puffy after reading the critique.

The response by Bruno Bonizzi and Jo Michell, though interesting largely rests on straw person arguments, false claims and the same kind of muddled thinking that we exposed in our original article.

One suspects though that there is a lot of common ground – given they are “sympathetic” to the “two main points” we raise in our original article:

1. “that many of the UK’s current economic problems have domestic causes and are not the result of the Brexit Brexit referendum”.

2. “the benefits of EU membership have been overstated”.

But where we fundamentally digress is that Bonizzi and Michell do not think that Brexit “provides a clear opportunity for implementation of progressive policy”.

At the outset, Thomas and I have been consistent on this issue both in our individual writing and in our many joint publications now.

The position needs stating clearly.

Brexit might turn out to be a total disaster for Britain if the Right stay in government and harden their neoliberal austerity bias.

If leaving the European Union provides a dynamic to renew and strengthen what is at present a fractured Right polity, then we would be the first to say it will end badly.

But what we have consistently argued is that there is a massive opportunity created by Brexit for British Labour to articulate a restated progressive voice by rejecting its neoliberal Blairite past.

We know there is a lot of debate and opinions about what membership of the EU actually allows Britain to do or not to do (for example, nationalisation of the railways etc).

The legalities are far from clear and would be finally adjudicated by the European Court of Justice rather than the British people via its legislature. That alone should tell the Left that EU membership compromises British democracy.

But Brexit means that the legal uncertainties are resolved and British Labour could confidently define a progressive path that allowed it to use its currency sovereignty to advance the well-being of all British citizens and residents.

Whether it would have the capacity to step up to that task is another matter and neither Thomas nor myself have suggested it is inevitable that will demonstrate the required leadership to succeed.

The failure of mainstream macroeconomics …

Bonizzi and Michell begin their critique by agreeing with us that the:

Predictions of immediate recession following the referendum … were clearly overstated to make political gains.

But then they say that our claim that the economics professions should hang its head in shame – for the inaccuracy of its economic predictions in case of a Leave victory – is unfair, since these predictions were “not endorsed by academic economists” and mostly peddled by “politicians or banks”.

They argue that the “academics confined their attention to the long-run effects”.

That statement is incorrect.

On May 23, 2016, just a month before the Referendum, the UCL Department of Economics issued a press release – UCL economists warn of historic economic risks from Brexit – which reported that:

47 economists from the UCL Department of Economics, ranked first in the 2014 Research Excellence Framework, have added their voices to a warning that the economic costs of Brexit would be high.

The 47 have together signed a statement now agreed to by over 200 other economists.

And what did they state?

Focusing entirely on the economics, we consider that it would be a major mistake for the UK to leave the European Union …

The uncertainty over precisely what kind of relationship the UK would find itself in with the EU and the rest of the world would also weigh heavily for many years. In addition, there is a sizeable risk of a short-term shock to confidence if we were to see a Leave vote on June 23rd. The Bank of England has signalled this concern clearly, and we share it.

These signatures confirm the breadth of the consensus among academic economists that Brexit would pose historic economic risks.

This letter was published in the Times newspaper and so received widespread coverage.

So nothing exclusively long-run about that.

And nothing “entirely” economics about that. They were trying to influence the Referendum outcome in favour of Remain.

On May 10, 2016, the National Institute of Economic and Social Research published its – Commentary – The economic consequences of leaving the EU – which said that:

… there is a degree … of consensus that leaving the EU would depress UK economic activity in both the short term (via uncertainty) and the long term (via trade).

This study was enthusiastically promoted two days later (May 12, 2016) by well-known British academic Simon Wren-Lewis who used it as authority to state “doesn’t everyone already know that nearly all economists think Brexit would have significant costs” (Source).

Further, on May 28, 2016 a few weeks before the Referendum, the British Observer published an article – Economists overwhelmingly reject Brexit in boost for Cameron – which reported on an opinion poll that the Guardian group had commissioned.

The Ipsos MORI poll – Economists’ Views on Brexit – surveyed “members of the Royal Economic Society and the Society of Business Economists”.

The survey recorded 639 responses from economists and asked them to differentiate the likely impacts of Brexit over the next 5 years (so short- to medium-term) and over 10-20 years (longer-term).

The sample of 639 included 366 (57 per cent) academic economists, the rest, largely, being economists working in the private or public sectors or for ‘think-tanks’ or charitable organisations.

Of the academic responses 258 out of 366 claimed that Brexit increased the risk of a “serious negative shock in the next 5 years”.

Of all the responses received 436 out of 639 claimed that Brexit increased the risk of a “serious negative shock in the next 5 years”.

In other words, the academic opinion was dominant that the short- to medium-term consequences were seriously negative.

But, moreover, in our article we criticised the mainstream macroeconomics profession in general and consider it to be a relatively cohesive group – whether they be academic or otherwise – united by a consistent approach to economic analysis.

In this blog post – Bank of England Groupthink exposed (January 8, 2015) – I discussed how Olivier Blanchard (who at the time was the chief economist at the IMF) wrote in his August 2008 article – The State of Macro – that research articles in macroeconomics now:

… look very similar to each other in structure, and very different from the way they did thirty years ago …

He said that they now follow “strict, haiku-like, rules”.

Graduate students are trained to follow these ‘haiku-like’ rules, that govern an economics paper’s chance of publication success and conditions type of techniques and methodology that is deployed.

I also considered the New Keynesian consensus that dominates the economics profession in this blog post – Mainstream macroeconomic fads – just a waste of time (September 18, 2009).

So the shockingly inaccurate short-term forecasts that the British Treasury and the Bank of England put out in the leadup to the Referendum cannot seriously be considered not exempt the mainstream macroeconomists who either produced the reports or supported them in the media in one way or another from damning criticism.

Which is what we did.

And in an event at London’s Institute for Government (January 5, 2017) – Andy Haldane in conversation – Bank of England’s chief economist admitted that:

… his profession is in crisis having railed to forsee the 2008 financial crash and having misjudged the impact of the Brexit vote.

The reporting of the event ((Source) said that:

Blaming the failure of economic models to cope with “irrational behaviour” in the modern era, the economist said the profession needed to adapt to regain the trust of the public and politicians.

Haldane himself said “the models we had were rather narrow and fragile. The problem came when the world was tipped upside down and those models were ill-equipped to making sense of behaviours that were deeply irrational.”

The same models dominate academic research in the field of macroeconomics.

When the editors finalised our Jacobin article they cut out what we thought was some useful detail.

An earlier draft included this detail:

The models used by the British government are called computable general equilibrium (CGE) models, which are informed by gravity models, and – much like their better known cousins, dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) models, and other macroeconomic forecasting models – they are highly complex and abstract mathematical models, the results of which are highly sensitive to the numerical calibration of the relationships in the models and the assumptions made about, for example, technology effects (‘returns to scale’). The models are notoriously unreliable and easily manipulated to achieve whatever outcome one desires. The British government has refused to release the technical aspects of their CGE modelling, which suggests they do not want independent analysts examining their ‘black box’ assumptions.

The point is that these models are uniformly used by mainstream macroeconomists within and outside the academy and have produced ridiculous results over many years.

They failed to predict the GFC, even though it was obvious to Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) economists as early as the late 1990s that a crisis was brewing.

They then failed to predict the depth of the negative impacts of austerity – remember the mantra “growth friendly austerity” or “fiscal contraction expansion”.

And they catastrophically failed in relation to the short-run impacts of the Brexit vote.

There is a consistent history of failure by mainstream macroeconomics to concur with the evidence.

Which makes it rather odd that Bonizzi and Michell would hold it out as a criticism of us that we:

… conflate these politically driven Brexit predictions with the problems of mainstream macro modelling and economists’ failure to predict the 2008 crisis.

Apparently, that is a “sleight of hand” on our behalf.

I don’t think the millions who lost their jobs during the GFC (many of who are still unemployed) despite the mainstream macroeconomists gloating that the ‘business cycle was dead’ and we were now in a ‘great moderation’ would think there was any ‘conjuring’ going on when we criticise the accuracy of the economists’ models.

Come Brexit – same models, same approach, same catastrophic errors – no conjuring on our behalf.

This criticim by Bonizzi and Michell is just one of countless examples that undermine the validity of their attack on us.

The linked to a Financial Times article (April 11, 2017) – Economists point finger of blame over Brexit forecasts – which reported on the Royal Economic Society annual conference, where some academic economists tried to backpeddle and absolve themselves of blame over the shockingly inaccurate Brexit forecasts.

Revisionism.

As we noted above, academic economists also came out in the press before the election claiming there would be ‘serious negative short-term results’ from Brexit.

Its on the public record. One can admit they were wrong but not that they didn’t say it.

Taking all that into account, Bonizzi and Michell’s defense of the economics professions is thus very hard to comprehend.

Just after the Referendum result, Ann Pettifor, who admitted to voting ‘Remain’, reflected on the outcome and summarised what most critical (progressive) economists now take for granted (Source):

We … call for an urgent, independent, public inquiry into the economics profession, its role in precipitating both the financial crisis of 2007-9, and the subsequent very slow ‘recovery’. Finally the role of the profession in the run up to the British European referendum campaign …

Economists have once again proved themselves not only irrelevant, but a dangerous irrelevance ….

Economists led the way to financial liberalisation of the past 40 years, which led to soaring levels of debt, crises and financial ruin. Economists dictated the terms for austerity that has so harmed the economy and society over the past years. As the policies have failed, the vast majority of economists have refused to concede wrongdoing, nor have societies been offered alternative economics policies …

Remain chose to focus on the economy – to the exclusion of almost all else. All the heavyweights of the economics profession – 10 Nobel Prize-winning economists, the OECD, the IMF, the Federal Reserve, the Bank of England, the NIESR, the Institute of Fiscal Studies, the London School of Economics – were wheeled out to warn the British people of economic facts known, and understood apparently, only to “experts”. The Financial Times amplified their voices and repeated their dire threats and warnings over and over.

But the “experts” and the economic stories they tell, have been well and truly walloped by the result of this referendum.

… the people are not to blame.

The economics profession, and their friends amongst the world’s financial elites, are to blame. They engineered their own political and financial bail-outs after the grave financial crisis of 2007-9. Economists cheered on politicians and effectively urged them to transfer the burden of losses on to those most innocent of the crisis …

Those powerful words link the neoliberal period to a series of catastrophes – including the GFC and the failed Brexit predictions.

For Bonizzi and Michell to claim we used “sleight of hand” to link the shocking Brexit predictions and other failures of “mainstream macro modelling” (including “failure to predict the 2008 crisis”) is simply a stunning denial of history and fact.

Post-Brexit Britain is not booming

Bonizzi and Michell then criticise us for “trying to paint the post-referendum period as a boom”.

If you re-read out article you will not find any statement that would suggest Britain is booming. We have never claimed that that the British economic situation is idyllic.

In fact we write that:

… the UK continues to face serious economic problems — suppressed domestic demand, ballooning private debt, decaying infrastructure, and deindustrialization …

But we simply claimed that “these have nothing to do with Brexit, but are instead the result of the neoliberal economic policies pursued by successive British governments in recent decades, including the current Conservative government.”

We clearly based our criticism of the scandalously inaccurate modelling pre-Brexit on an appraisal of the facts that are available some two years since the Referendum.

It is obvious that:

1. GDP has grown by 3.7 per cent since the Vote.

2. Unemployment is lower.

3. British manufacturing is growing strongly – via better world trade conditions.

4. Capital formation was strong in 2017 (highest of any G7 country).

We don’t call that a boom. We simply state the facts and counter pose them against what the mainstream economists were predicting would happen – almost the opposite of what has happened.

So, to their discredit, Bonizzi and Michell are just making stuff up when they make that claim about us.

They specifically take exception to our statement:

Total investment spending in the UK — which includes both public and private investment — was the highest of any G7 country during 2017 …

They write that this is:

… is simply incorrect. Investment growth was high, but from a low base. By historical standards, investment spending remains low, and is in fact the lowest among G7 countries as a percentage of GDP.

And there is the sleight of hand!

First, note they throw in some cloud – “from a low base” – to sow doubt about the veracity of our claim. Of course, it is from a low base. The UK endured a policy-driven recession for many quarters which derailed capital formation.

We all know that and it is irrelevant for the point we were making about the growth of British investment post-Referendum.

Second, the proof, as they say, is in the pudding.

In our article, we linked to a Financial Times report (March 29, 2018) – UK investment spending leaves G7 rivals trailing – to provide an easy to access evidence trail.

That article was summarising the latest ONS data on British investment:

Annual growth in investment spending in the UK was the highest of any G7 country during 2017, according to figures published by the Office for National Statistics on Friday …

The figures suggest that uncertainty over the outcome of the Brexit negotiations has not chilled overall investment spending in the UK.

Was that Financial Times article reporting accurately?

Well, lets go to the source and see what the Office of National Statistics published.

The specific Office of National Statistics release (March 30, 2018) – Business investment in the UK, revised: October to December 2017 – provided some “International comparisons of GFCF” as part of that release.

The ONS conclude:

Between 2016 and 2017, the UK had the strongest growth in gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) of any G7 nation at 4.0%

QED!

Here is the graph:

Bonizzi and Michell’s sleight of hand?

Note that Bonizzi and Michell say that British investment spending “is in fact the lowest among G7 countries as a percentage of GDP” (our emphasis added).

Our article was talking about investment growth not investment as a proportion of GDP. They are two different things altogether and so why try to blur the argument? Well it is because they did not have a legitimate point and so they made one up.

Note also that the investment ratio (as a proportion of GDP) also hasn’t declined since the Brexit vote.

Trade graphs

Bonizzi and Michell agree with us that “the economic benefits of single-market membership have been overstated”.

But they take exception to one of the graphs we produced (reproduced here).

This graph was originally produced for my (Bill) blog post – The facts suggest Britain is not as reliant on EU as the Remain camp claim (April 16, 2018) – and I fed it into our Jacobin article.

Two things are obvious from the graph:

1. There was no particular acceleration in British exports as a share of their total exports to the EU or to the nations now comprising the Member States of the Eurozone after it accessed membership of the EU in 1973.

2. After the introduction of the Single Market, twenty years later, the British share of exports going to the EU and the EMU flattened and after the 2005 (pre-GFC) started to decline rather sharply.

In other words, Britain has been diversifying its exports and is less reliant on the EU than it was say in the early 1990s.

Exports to China have risen from virtually zero in 1973 to 4.8 per cent of the total in 2017, while exports to the EU are falling towards the 1973 levels.

Bonizzi and Michell say we “overemphasize the significance” of it and that the graph “does not imply ‘a negligible advantage to the UK of being a member of the EU’”, but only that non-European trade has been growing at a faster pace.

Yes, the graph is about shares rather than levels. We obviously understand that point.

And so we added a further piece of evidence that Bonizzi and Michell deliberately chose to ignore, presumably because they would not then be able to make their erroneous point.

We wrote:

A further observation drawn from the IMF Directions of Trade database is that while global exports have grown by 5 times since 1991 and the advanced economies exports have grown by 3.91 times, the EU exports have only grown by 3.7 times and the Eurozone by 3.4 times.

Thus, in both relative and absolute terms the Single Market has not had the major postive effect that the anti-Brexit lobby would have us believe.

It is, of course, always possible that without the Single Market, outcomes would have been much worse. But that conjecture would be difficult to sustain.

Bonizzi and Michell try to argue otherwise, saying that “we do not know what would have happened if the UK had remained outside the EU. It is perfectly plausible that trade would have declined.”

How is it perfectly plausible given the massive growth of South and East Asia, and the growing contribution of that growth to British trade?

Countries such as Australia, which had relied on Britain for trade under Commonwealth agreements and was abandoned when Britain joined the EU in 1972, relatively quickly reoriented their external focus to Asia and trade has boomed ever since.

It is much more plausible that in the absence of EU membership, British trade would have similarly expanded.

So the evidence does support the Cambridge study study published by the Centre for Business Research (CBR) at Cambridge University, which we quote, that suggests “a negligible advantage to the UK of being a member of the EU” in this regard.

Curiously, Bonizzi and Michell then criticise us for claiming that we:

… go on to argue that trade is not beneficial.

We actually do not say that in our article.

This is just a straw person argument introduced by them.

What we actually show is that there is no evidence that trade liberalisation (under the ‘free trade’ mantra) does no necessarily lead to increased trade, as the neoliberal era – and as the single market – shows.

The two things are very different.

Bonizzi and Michell get muddled

Then the muddled thinking kicks in.

Bonizzi and Michell claim that:

… had the UK remained outside the single market, either it would have complied with the ongoing development of EU regulatory structures in order to maintain and develop its pan-European and global production chains, or faced gradual disintegration with the European economy.

In other words, Bonizzi and Michell are saying that the UK could have continued to trade perfectly well with the EU without joining the EU (as in the case of say, Norway).

So how can they also claim that “it is perfectly plausible that trade would have declined” had the UK not joined the single market?

This is classic Left-TINA thinking which goes like this: As a result of global capitalism, nations have lost significant sovereignty and so they have to accept either everything (that is, full harmonisation and financial integration) or autarchy (frozen out).

Apparently, there is no middle ground is possible in this narrative.

The evidence of many nations clearly shows there is middle ground.

Brexit and deindustrialisation

Bonizzi and Michell further claim that we ignore the fact that Brexit will necessarily entail a restructuring of British capitalism, which in turn implies economic costs, especially in the short term.

However, the idea that we just ignore adjustment costs is ludicrous.

Any major legal changes within an economy create ‘adjustment costs’. Our position is clear.

If the ‘free market’ narrative wins out in post-Brexit Britain then there will be massive costs.

However, we believe that this restructuring – especially if steered by a future Labour government – could prove positive for the British economy.

In this regard, we quoted The Economist article (February 8, 2018) – Britain’s long-suffering makers are enjoying a once-in-a-generation boom – which noted that despite the uncertainty concerning the negotiations with the EU:

… Britain’s long-suffering makers are enjoying a once-in-a-generation boom … manufacturing is seeing its strongest growth since the late 1990s …

We noted that this virtuous cycle has been largely due to a growing demand for British exports, which are reaping the benefits of the lower pound and improved world trade conditions.

But, further, as The Economist notes that Brexit-induced shifts have engendered a much-needed “rebalance towards the manufacturing sector.”

And they say this will mean that the British economy will be “Relying less on boom-and-bust financial services” which “will put the economy on a surer footing”.

All of that discussion is in our Jacobin article and so Bonizzi and Michell’s claim that we ignore it is ridiculous.

We also provide other evidence trails including:

1. Survey evidence from the British manufacturers’ association EEF (Source).

2. Citation of a new a report by Heathrow Airport.

3. And the research from the Centre for Economics and Business Research (CEBR), cited above.

4. Links to an Op Ed by Guardian Economics editor Larry Elliott who in his article (August 20, 2016) – Brexit Armageddon was a terrifying vision – but it simply hasn’t happened – wrote that in many respects:

Brexit has been a help. It has forced the government to take a long, hard look at the British economy – something that would not have happened without the shock administered by the referendum. It’s brought home the fact that most of Britain feels disconnected from the economic story peddled by successive governments.

For decades, there’s been a tendency for businesses to meet rising demand by employing cheap labour rather than by investing in modern equipment. Large chunks of the economy are characterised by low skills, low wages, and low productivity. As the Resolution Foundation noted this week, companies that rely on the ability to import low-cost employees from the EU are going to have to rethink their business models. This is not necessarily a bad thing.

The government has responded to Brexit by soft-pedalling on austerity, by contemplating spending more on infrastructure and by committing itself to an industrial strategy. A degree of scepticism is warranted here. The referendum has made change possible: it doesn’t guarantee it will happen.

By way of summary, our Jacobin article provided significant external resources to support our argument that a properly designed policy intervention in post-Brexit Britain can generate beneficial outcomes contrary to the long-run forecasts of doom and gloom coming from the mainstream economists.

Brexit is a Right-wing plot or the work of racists – how did we overlook that!

Bonizzi and Michell then accuse us of not acknowledging:

… that Brexit is being driven by a UK government with broadly two factions: center-right Remainers and, further to the right, a Leave bloc populated with libertarian fantasists dreaming of an ultra-deregulated, off-shore, low-tax utopia.

Hello! Is anyone there?

The fact is that we don’t ignore this point either.

As we outline in our new book Reclaiming the State: A Progressive Vision of Sovereignty for a Post-Neoliberal World (Pluto Books, 2017) – we simply do not subscribe to the determinism that paralyses the Left discourse.

The notion that leaving the EU will “inevitably” benefit the Right is not new. In fact it was a common argument of the Left even before the referendum, with claims that a Leave victory would have “inevitably” benefited the right.

It is the same sort of argument that the Left use when discussing any sort of ‘Exit’ – Greece, etc.

Well, in the two years since the Leave vote the opposite has happened.

As even John Weeks, a committed Remainer, acknowledged in his openDemocracy article (July 31, 2017) – No Bregrets: does Brexit hold hope for progressives after all?:

… pro-EU progressives will find it hard to deny that the referendum result we fought to prevent has led to events beyond our most optimistic hopes, with the fall of the Cameron government and stunning success of the Labour Party in the 2017 general election. I deeply regret leaving the European Union, but must accept that the probability is great that the June 2016 referendum will in due course result in a UK government committed to social democracy, not neoliberalism.

A very powerful statement. Come in Jeremy Corbyn and his Labour team.

One would have to be blind not to see that Corbyn’s rise is also the result of a process fo repoliticisation engendered by Brexit.

Similarly, Bonizzi and Michell reprimand us for ignoring that “the referendum result was driven by anti-immigrant sentiment”.

We don’t ignore that; we simply believe that Brexit is the symptom not the cause, and that reversing Brexit won’t eliminate the root causes of the phenomenon. In fact, the contrary is likely to happen.

The EU utopia … how did we overlook that!

Finally, Bonizzi and Michell argue that we overlook the “progressive” benefits of EU membership, including – they write:

… social protection, environmental regulation, and academic and scientific cooperation.

We don’t ignore that EU membership has its benefits.

We simply believe that:

1. The costs outweigh the benefits (self-evidently so in the case of eurozone countries).

2. Many of the benefits cited by the authors – scientific cooperation, the Erasmus programme, etc. – could be enjoyed even without the economic super-structure of the EU, as a result of international agreements between countries.

For example, Australian researchers have no trouble creating very robust and effective working relationships with academics in Europe. Not being part of the EU has never stopped us doing that.

As for the notion that the EU defends “social protection”, perhaps we should ask the people of Greece if they agree, just as we should ask the people of Norway if a country can enjoy high levels of social protection outside the EU.

More in general, not only have EU institutions overseen in recent years a brutal assault on the social and economic rights of the citizens of Europe, particularly in the periphery; they have also proven utterly powerless to prevent member states (such as Hungary and Romania) from violating the rights of their citizens and/or from disregarding some of the basic tenets of the EU, such as the Schengen Treaty.

Hence, the contention by Bonizzi and Michell that the EU is the only thing preventing the UK from plunging into a quasi-fascist dystopia is untenable.

The fate of Britain post-Brexit will depend on the strength of its democracy and the mobilisation of progressive narratives.

Finally, the Bonizzi and Michell claim that the argument we present in the original Jacobin article:

… is based on a non-sequitur: the benefits of the EU and the costs of leaving are overstated, therefore leaving is the only progressive option. They offer nothing to bridge the gap between premise and conclusion — other than some vague comments about nationalization and state aid rules.

Our argument is, in fact, very simple and hinges on two crucial points:

1. Britain would have much more space to pursue radical economic measures (such as those foreseen in Corbyn’s manifesto) outside than inside the EU.

At present there is a lot of legal argument advanced by the Left about what Britain can and cannot do within EU legislative frameworks. The arguments claim that there is nothing in EU law that would restrict Corbyn from introducing a very radical agenda and wiping out neoliberalism in British policy.

We disagree, but that is a separate argument. However, what Brexit will deliver is freedom from the uncertainty of all this legal interpration and recourse to the European Court of Justice.

In other words, for good or bad, Britain’s legislature will be uncompromised by these external rules and courts.

2. A soft Brexit or even worse a Brexit In Name Only (BINO) would kill much of the political energy hitherto engineered by Brexit and harnessed by Corbyn.

As Richard Tuck wrote (August 21, 2017) in his Op Ed – Long read: Brexit is a prize within reach for the British left:

If I am right in supposing that this new surge in left-wing politics is the result of Brexit, it would be suicidal to overturn it. We can see the dangers of doing so very clearly in the case of the working-class UKIP voters, particularly in the North, who felt it was now safe to return to Labour; but it is also dangerous indirectly and in the long term for the newly-energised younger voters of the South. They may to some degree support the EU, but their new energy is a product of Brexit, and not in the sense that it is merely a reaction to it. Like everyone else, they have sensed the opening-up of possibilities long denied to them, and even if they want the EU they surely do not want the return to power of the kind of politician the EU necessarily breeds.

We concur with that view.

Conclusion

Finally, it is only in the last paragraph that Bonizzi and Michell reveal the bias that informs their whole article:

Although we are under no illusions as to the shortcomings of the EU, we remain committed to the view that these are overshadowed by the political risks of fragmentation. A far-right hard Brexit is a more likely scenario than a progressive one. The progressive position is, while accepting the result of the referendum, to seek to maintain ties with Europe and work with other progressives towards the goal of reform.

This is the nub of the conflict within the Left.

In Reclaiming the State: A Progressive Vision of Sovereignty for a Post-Neoliberal World (Pluto Books, 2017) – we provide a coherent evidence-based argument to show that we do not consider progressive reform of the EU to be an option and thus our approach to Brexit is obviously informed by that.

Just like their belief in the EU’s reformability informs their opposition to Brexit.

Our writing (together and individually) has regularly updated readers on developments within Europe – most recently – Die schwarze Null continues to haunt Europe (May 21, 2018) – which demonstrates that the Europhile Left’s hope that meaningful progressive reform is just around the corner is a pipe dream.

joseba says:

Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour vs. the Single Market

By Costas Lapavitsas

If the next Labour government is to be truly transformative, it has to free itself from the constraints of the single market.

(https://jacobinmag.com/2018/05/corbyn-labour-eu-single-market-economic-policy)

“Workers in Britain remain broadly in favour of Leave, but need information, arguments and, above all, political leadership from the Left, which used to be their voice. Unfortunately, the state of discourse on the Left shows that many have failed to come to terms with the underlying realities of the referendum decision. It is time to stop clinging to some imagined status quo ante. The Left should see this moment as a historical opportunity to transform Britain’s economy, free from the constraints of the Single Market.”

joseba says:

Kantu zail bat, oso zaila

https://www.unibertsitatea.net/blogak/heterodoxia/2018/06/01/kantu-zail-bat-oso-zaila/