Bill Mitchell-en The penny drops – WSJ acknowledges UK government can never run out of money1

(i) Sarrera2

(ii) Herrialdeen moneta propioa eta zorra: kazetariak eta politikariak gezurretan3

(iii) WSJ-ren tesi garrantzitsuak: DTM-koak gehienak4

(iv) Argudio batzuk5

(v) Bonoen grafikoa, 2007tik 2016ra6

(vi) Estaldura ratioak7

(vii) Ez-egoiliarren ‘gilt’ merkatuak8

(viii) Ez-egoiliarren ‘gilt’ merkatua, Brexit eta gero9

(ix) Ez-egoiliarren libra esterlinako gordailuak10

(x) Datuak ados daude DTM-k esaten duenarekin11

(xi) WSJ-ren argudioak zuzenak dira:

(a)Britainia Handiari dagokionez12

(b) Euroguneari dagokionez13

(x) Argudioak DTM-koekin bat datoz14

Ondorio nagusia:

“Certainly, core MMT knowledge notes that “Because sovereign bonds are as safe as cash”. There is no risk of default on financial grounds.

Even the WSJ now acknowledges that.”

2 Ingelesez: “When a News Corp newspaper starts writing articles that reflect the insights provided by Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) you know that progress in the dissemination of those ideas is being made. Even if they don’t get things exactly right. The Dow Jones & Company (owned by News Corp) daily, the Wall Street Journal carried an article last week (October 31, 2016) – Message from the Gilt Market: U.K. Can Never Run Out of Pound – which leaves no room for doubt.”

3 Ingelesez: “The London-based journalist Jon Sindreu wrote that “Among facts that take a stubbornly long time to sink in, here’s one: Countries that borrow in their own currencies never have to default on their debt”. So never again allow a person in your company to suggest otherwise. There are many like facts that seem to evade the understanding of journalists, politicians and others who desire to push the neo-liberal line. I say ‘seem’ because it is certain that many of these neo-lib banner carriers know full well they lie when they make claims about currency-issuing governments running out of money and the like. They are ideological warriors after all and in war, anything seemingly goes.”

4 Ingelesez: “The main thesis entertained in the Wall Street Articles is as follows:

1. The mainstream pundits thought the Brexit vote would see foreigners sell of British government bonds in large quantities. They didn’t. Exactly the opposite has happened.

2. What has actually happened? The exchange rate depreciation has a meant that “British assets have become automatically cheaper to foreigners”. So the adjustment has come from the currency conversion rather than the asset price.

3. Capital has not actually flowed out of Britain. All that has happened is that the pound has been “repriced”

4. Why? Because “Britain is a developed country with liquid financial markets that issues debt in its own currency. Unlike Greece or Spain, which could certainly run out of euros, the U.K. can always print more pounds” (a core MMT proposition).

5. The claims that the central bank is independent and therefore Britain is like Greece is false. The reality is that “the role of central banks has always been intimately tied to managing the government’s debt” (a core MMT proposition).

6. QE has meant that the Bank of England “now owns roughly a third of the £1.5 trillion gilt market”. No inflation or anything other bad things have happened as a result.

7. “Even in the eurozone, the European Central bank has shown it has the power to end bond selloffs” – a point I regularly make. The government is in charge not the bond markets (a core MMT proposition).

8. “Credit-rating agencies have warned for decades about Japan’s ever-growing debt pile, but its bonds continue to trade at record highs”. The credit-rating agencies are charlatans at best. They have no significant interest on the bond dynamics of currency-issuing governments such as Britain or Japan (a core MMT proposition).

9. “sovereign bonds are as safe as cash” as long as the government issues its own currency and only issues bonds in that currency (a core MMT proposition).”

5 Ingelesez: “So lets consider a few of the arguments.

The WSJ article asserts plainly (and correctly) that:

Countries that borrow in their own currencies never have to default on their debt.

But then it goes on to claim that the “last few months have tested this notion again”.

Really? How?

Apparently, in the period leading up to the Brexit vote, “investors and analysts” (that lot!) warned that “scared foreigners could dump British sovereign bonds, driving the government’s borrowing costs to skyrocket.”

As the article notes, these predictions of doom were very, very wrong.

But backstep one.

If the demand for government bonds declines, the prices in the secondary market decline and the yield rises. How come?

In macroeconomics, we summarise the plethora of public debt instruments with the concept of a bond. The standard bond has a face value – say $1000 and a coupon rate – say 5 per cent and a maturity – say 10 years. This means that the bond holder will will get $50 dollar per annum (interest) for 10 years and when the maturity is reached they would get $1000 back.

Bonds are issued by government into the primary market, which is simply the institutional machinery via which the government sells debt to the non-government bond dealers.

In a modern monetary system with flexible exchange rates it is clear the government does not have to finance its spending so the the institutional machinery is voluntary and reflects the prevailing neo-liberal ideology – which emphasises a fear of fiscal excesses rather than any intrinsic need for funds (of which the currency-issuing government has an infinite capacity).

Once bonds are issued they are traded in the secondary market between interested parties. Clearly secondary market trading has no impact at all on the volume of financial assets in the system – it just shuffles the wealth between wealth-holders. Please read my blog – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3 – for more discussion on this point.

Most primary market issuance is now done via auction. Previously, governments (such as in Australia) ran what were called ‘tap systems’ of bond issuance.

Accordingly, the government would determine the maturity of the bond (how long the bond would exist for), the coupon rate (the interest return on the bond) and the volume (how many bonds) that was being sought. If the private bond traders determined that the coupon rate being offered was not attractive they would not purchase the bonds. The central bank, typically, would then step in an buy up the unwanted issue.

Under the auction system, the issue is put out for tender and the market would determine the final price of the bonds issued. Imagine a $1000 bond had a coupon of 5 per cent, meaning that you would get $50 dollar per annum until the bond matured at which time you would get $1000 back.

Imagine that the market wanted a yield of 6 per cent to accommodate risk expectations (inflation or something else). So for them the bond is unattractive and they would avoid it under the tap system. But under the tender or auction system they would put in a purchase bid lower than the $1000 to ensure they get the 6 per cent return they sought.

The mathematical formulae to compute the desired (lower) price is quite tricky and you can look it up in a finance book.

The general rule for fixed-income bonds is that when the prices rise, the yield falls and vice versa. Thus, the price of a bond can change in the market place according to interest rate fluctuations.

When interest rates rise, the price of previously issued bonds fall because they are less attractive in comparison to the newly issued bonds, which are offering a higher coupon rates (reflecting current interest rates).

When interest rates fall, the price of older bonds increase, becoming more attractive as newly issued bonds offer a lower coupon rate than the older higher coupon rated bonds.

Further, rising yields may indicate a rising sense of risk (mostly from future inflation although sovereign credit ratings will influence this).

But they may also indicate a recovering economy where people are more confidence investing in commercial paper (for higher returns) and so they demand less of the risk free government paper.

So you see how an event (yield rises) that signifies growing confidence in the real economy is reinterpreted (and trumpeted) by the conservatives to signal something bad (crowding out, increased cost of government spending).

The reason long-term yields would be rising in this case is because investors were diversifying their portfolios and moving back into private financial assets.

The yield reflects the last auction bid in the bond issue. So if diversification is occurring reflecting confidence and the demand for public debt weakens and yields rise this has nothing at all to do with a declining pool of funds being soaked up by the binging government!

But all of that has nothing to do with the real resource costs embodied in goods and services that governments purchase.

Which bears on the claim in the WSJ article that a declining demand for government bonds drives “the government’s borrowing costs to skyrocket”.

For a sovereign government that issues its own currency there is no binding revenue constraint on government spending. The interest servicing payments come from the same source as all government spending – its infinite (minus one cent!) capacity to issue fiat currency.

There is no ‘cost’ – in real terms to the government doing this.

The concept of ‘more or less expensive’ is therefore inapplicable to government spending in this situation.

The cost of government spending is the real resources that are deployed in the production of the goods and services being purchased rather than the fiscal balance entry in the Treasury books.

Rising bond yields do not measure these opportunity costs.”

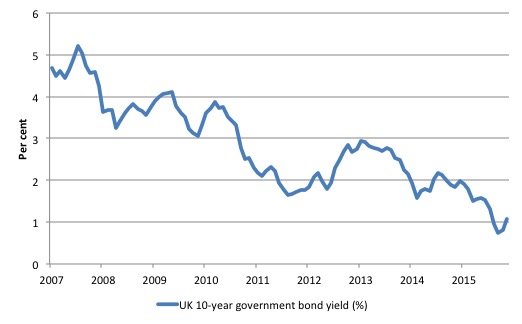

6 Ingelesez: “The following graph shows the movement in the British 10-year government bond yield from January 2007 until September 2016.

In June 2016, the ten-year bond yield was 1.3105 per cent. It dropped to 0.8243 per cent by the end of September 2016 as demand for bonds increased. By the end of October 2016 it had risen slightly to 1.078 per cent.

Nothing significant is going on here.”

7 Ingelesez: “Another way of assessing the taste for British government debt is to consider the so-called bid-to-cover ratio. The bid-to-cover ratio or the coverage ratio is the value of the bids relative to the tender amounts of the bonds being issued.

A ratio of 1 means that there is enough demand to match the issuance intentions of the government.

The coverage ratios are typically high for the Australia, US, the UK, Japan and most nearly all sovereign nations where the relevant data is publicly available.

The long history of bid-to-cover ratios in the bond markets of currency-issuing nation suggest that the investors cannot get enough public debt. When debt levels start falling below some level (that will provide liquidity to futures markets, for example) the private bond traders demand the government issues more debt even if they are running surpluses.

A word of caution. Even using the ratio assumes it matters. The reality is that as the British government is not revenue-constrained (it issues its own currency), it could abandon the auction system whenever it wanted to if the ratio fell to 0.00001.

It is also highly interpretative as to what the ratio signals. It certainly signals strength of demand but how strong becomes an emotional/ideological/political matter.

Even if you believed that the government was financing its net spending by borrowing, then a bid-to-cover ratio of one would be fine – enough lenders to cover the issue.

Some commentators think that 2 is a magic line below which disaster is imminent. There is no basis at all for that.

There is also no basis in the statement that a ratio above 3 is successful and by implication a ratio below 3 is unsuccessful. After all, anything above 1 tells you that some investors do not get their desired portfolio. That sounds like a failure to me.

The bid-to-cover for British government gilts is not plunging. The large pension funds have been falling over each other to keep stocking up on government debt because they know it represents more corporate welfare!

Indeed, in the May 5, 2016 auction for 10-year bonds, the bid-to-cover ratio was 1.79. The ratio in the July 7, 2016 10-year bond auction rose to 2.33, indicating a rise in demand for the assets.

In the September 6, 2016 auction, the ratio was 1.73 and 2.01 in the October 19 auction.”

8 Ingelesez: “We move on.

The WSJ article then documents the recent movements in the so-called ‘gilts market’ in the UK, and, in particular, the reduced holdings of foreign residents.

Apparently:

Because they own about a quarter of the market, the U.K. Treasury itself said this could be a serious problem.

Which really just goes to show that H.M. Treasury is a source of misinformation.

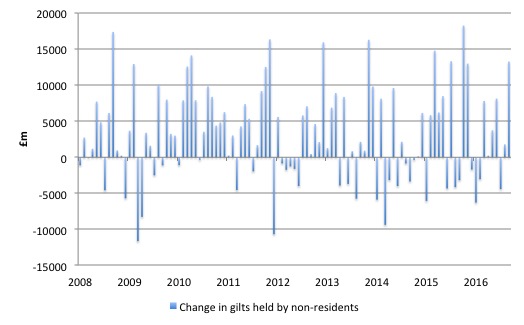

You can get detailed data on the monthly movements in gilt holdings by sector etc from the Bank of England – go to the statistical database and search for “Monthly adjusted changes of Central Government issues of sterling gilts held by non-residents (in sterling millions) not seasonally adjusted” (or series LPMB9P6).

The following graph shows the monthly movements since the onset of the GFC (January 2008) until the end of September 2016. You can see there is considerable shifts between months in these holdings.”

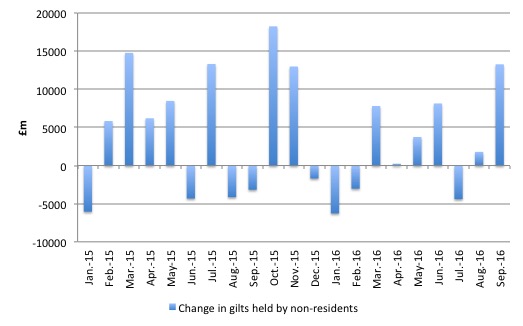

9 Ingelesez: “The next graph focuses on the more recent period (since January 2015), to bring the Brexit vote period into more relief. In the month after the Brexit vote, non-residents sold off gilt holdings of £4,403 million. In August, there was a reversal of £1,793 million in purchases and in September, foreigners boomed back into the British bond market with a £13,272 million buy up.”

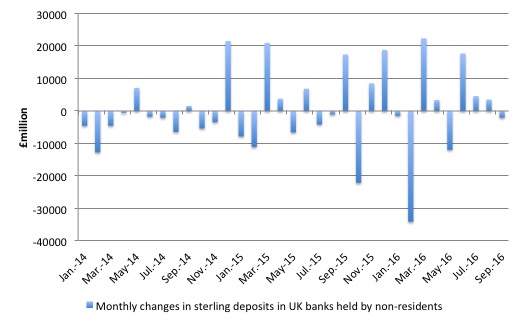

10 Ingelesez: “If we examine the Monthly changes of UK resident monetary institutions’ (excluding the central bank) sterling deposits from non-residents (Bank of England series LPMB2VG) we get a feel for whether foreigners are dumping the pound in any significant volumes.

The following graph shows the data from January 2014 to September 2016.”

11 Ingelesez: “As the Wall Street Journal article notes:

The data show that not many actual flows out of Britain have taken place.

The contention, which I agree with (and is a core MMT proposition) is that the bond markets will not dump the British government bonds in any significant volumes because:

Britain is a developed country with liquid financial markets that issues debt in its own currency. Unlike Greece or Spain, which could certainly run out of euros, the U.K. can always print more pounds.

Moreover, the central bank will always stand ready to purchase government bonds if the private demand falls. In doing so, it can always control yields and drive them to zero or whatever should it choose (a core MMT proposition).

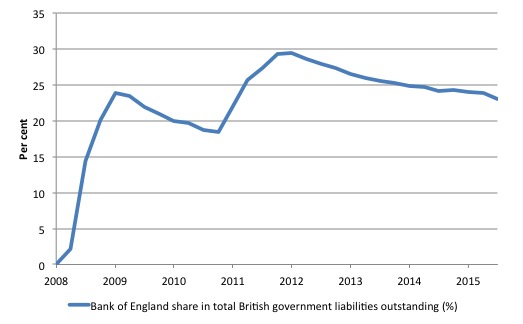

The following graph shows the Bank of England’s share in total British bonds outstanding since December-quarter 2008 (when it held zero central government liabilities).

By the June-quarter it had accumulated £429,323 million. Between the December-quarter 2008 and the June-quarter 2016, the Bank of England purchased 34 per cent of the total change in British central government bonds issued.

It now holds 23 per cent of the total debt outstanding.”

12 Ingelesez: “As the Wall Street Journal article argues (correctly):

While the independence of central banks—a choice states themselves have made—is often highlighted as a counterargument to the notion that currency-issuers never have to default, their operations in money markets are done through government bonds and bills, ensuring a liquid and stable market for them. In fact, the role of central banks has always been intimately tied to managing the government’s debt.

And, as the graph above shows – the central bank can purchase whenever it likes (the spikes are its QE program) and as much as is available.”

13 Ingelesez: “The other important point the WSJ article makes is that:

Even in the eurozone, the European Central bank has shown it has the power to end bond selloffs.

I have made this point often – the ECB saved the Eurozone from collapse in May 2010 when it introduced the Securities Markets Program and started buying up distressed Member State debt.

Immediately, the bond markets were dealt out of the game and the ECB pushed spreads down rapidly (against the Bund).”

14 Ingelesez: “The ECB could:

1. Buy all the outstanding government debt and write it off immediately without any negative consequences. It should.

2. Fund all Member States deficits to help growth return. It should.

Even the WSJ is now recognising that reality.

It also mentions (as above) how the criminal credit-rating agencies are irrelevant and the example of Japan proves that to be so in no uncertain terms.

All of these propositions, observations etc are core MMT knowledge.

They are denied by most mainstream economists. Perhaps now the WSJ is starting to crawl out of its neo-liberal hole and provide some better understanding of how things actually operating, the denials will fade into the ether.”