Hasierarako, ikus Alemaniako finantza ministroa eta EBko estatu desberdinen aurrekontuen kontrola

Segida:

Bill Mitchell-en The Eurozone ‘house of cards’ to collapse – doomed from the start1

Sarrera:

(a) Otmar Issing-i egindako elkarrizketa2

(b) EBZ, NMF eta Europako Komisioa3

(c) Eurogunearen afera aspalditik dator, arazoa neoliberalismoari dagokio4

Artikuluan ukitutako zenbait puntu garrantzitsu:

(i) BPGren indizeak5

(ii ) Zer ote da Eurogunea?6

(iii) Moraltasunaren hizkera pizgarri fiskalen aurka7

(iv) Issing, EBZ eta banku sistema8

(v) Diru laguntzak, erreskateak (‘bailouts‘)9

(vi) EBZ-ren gobernu bonoen erosketa10

(vi) Alemania aurka jarri zen11

(vii) Securities Markets Program (SMP) delakoa diru-laguntza, erreskate fiskala zen12

(viii) SMP eta PIIGS13

(ix) SGP (Stability and Growth Pact) delakoaren murrizketak eta euroguneko kideak finantzatzeko bono pribatuen merkatuak14

(x) Alemaniako bonoak eta EBZ15

(xi) Zer etorriko da gero? Gobernuak zor gehiago metatuko dute… eta gero, egunen batean, karten etxea gainbehera eroriko da16

(xii) Issing-en 2011ko artikulu17

(xii) Issing-en oraingo elkarrizketan: EBZ prozesu politikoaren menpe. Baina afera neoliberalismoari dagokio18

(xiv) Sistema federalaz: entzun ez ziren aholkuak eta Maastricht19

(xv) Sistema federala, ahalmen fiskal federala eta banku zentralaren moneta ahalmena20

(xvi) Pragmatismoa: SMP; Frantzia eta Alemaniako defizitak 2003an; Espainiako neurri fiskalen bortxaketa geroago21

(xvii) Issing-ek dioenez, “The Stability and Growth Pact has more or less failed.”22

(xviii) Grezia eta Espainia23

(xix) EBZ eta zaborrezko bonoak24

(xx) Europar Batasun politikaren ezintasuna25

(xxi) Irtenbiderantz: aurrekontu-subiranotasuna eta monetaren subiranotasuna26

Ondorioak:

(1) Martxan dagoena sistema atzerakor eta deflazionarioa da27

(2) Langabezia pilo bat norma da, eta handituz doan pobrezia emaitza28

(3) Ondorioz, prozesu politikoak muturrerantz mugitzen ari dira29

(4) Orain, ordenatuko haustura da biderik onena30

2 Ingelesez: “There was an interesting interview published in the financial market journal Central Banking this week with Otmar Issing, who was the ECBs first chief economist and a former European Central Bank executive board member. He predicted that as a result of the political corruption of the monetary union ideal, “the house of cards will collapse.”

3 Ingelesez: “He was referring to the claim that the ECB has become captured by politicians and technocrats in the IMF and the European Commission such that it is now violating essential central banking principles, in addition, to Treaty obligations that were designed to safeguard the financial stability of the system. I have some agreement with his overall view that a federal solution to the Eurozone ills is not viable.”

4 Ingelesez: “But I do not agree that the ills of the Eurozone stem from recent political decisions – to pressure the ECB to engage in QE or other interventions. The reality is that the flawed design of the Eurozone, which reflected the ideological hold of neo-liberalism on the integration discussions in the 1980s and beyond, meant that the only effective fiscal capacity in the currency union was held by the ECB. If the ECB had not started buying up government bonds in May 2010, the monetary union would have collapsed about then. The whole problem is that neo-liberalism brought these Member States together into a monetary architecture that was doomed from the start.”

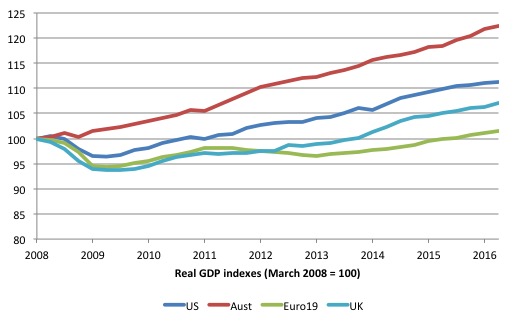

5 Ingelesez: “The following graph shows real GDP indexes (March 2008 = 100) 4 the US, Australia, the UK, and the 19 Eurozone nations.

Ikus irudia:

Several points are of relevance:

1. The depth of recession was relatively similar for all the nations shown except for Australia, which did not experience a technical recession during the GFC because the federal government introduced an early and fairly sizeable fiscal stimulus and maintained it through to 2012.

2. Both Australia and the US maintained their fiscal stimulus without major austerity events.

3. After an initial stimulus, the UK followed the Eurozone (upon the election of the Conservative government in May 2010) down the austerity path and their experiences were very similar as a result. The UK in a sense was in denial of its currency-issuing capacity.

4. By 2012, George Osborne facing a major electoral backlash abandoned the austerity path and allowed the deficit to float and expand and at that point the British economy resumed growth and departed from the Eurozone growth path.

5. The interesting comparison is at what point these nations crossed back over the 100 index point line, which is the point at which the economy started to grow again relative to the March 2008 peak.

In the case of the US this occurred in the December-quarter 2010 (11 quarters after peak). In the case of the UK it occurred in the December-quarter 2013 (23 quarters after peak). For the Eurozone, it took 30 quarters (September-quarter 2015) and the index has improved only 1.4 per cent since.

If we examined movements in real output and real per capita income in a federal system such as Australia since 2008 we would find very little discrepancy among the component states and territories. Indeed, while Tasmania has lagged somewhat behind it is still ahead of where it was when the GFC began.

The Australian economy, overall, is 22.4 per cent larger than it was in 2008. The US economy is 11.3 per cent larger and the UK is 7.1 per cent larger. The performance of the US and UK economies is fairly poor but shines out when compared to what has happened in the Eurozone.

Compare that to the discrepancies that exist between the Member States within the Eurozone where the Greek economy is now 27 per cent smaller than it was in the March-quarter 2008, Italy is 8 per cent smaller, Portugal is 6 per cent smaller and the Eurozone overall is only 1.1 per cent larger.”

6 Ingelesez: “Question: Is the Eurozone an outlier? Answer: Obviously.

I cover the problems of the Eurozone from their historical beginnings in my current book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale.

There was an interesting interview published in the financial market journal Central Banking this week with Otmar Issing, who was the ECBs first chief economist and a former European Central Bank executive board member.”

7 Ingelesez: “Issing frequently intervenes in the public debate with a high-handed morality dressed up as economic commentary. Indeed, the language of morality has been prominent in the public commentary by conservatives, which has reflected the religious nature of the crusade against fiscal stimulus.

For example, Financial Times journalist Wolfgang Münchau abhorred the September 2009 decision by the French government to abandon any aim to reduce its fiscal deficit to below 3 per cent by 2012 and claimed other governments (Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain) were similarly recalcitrant.

In contradistinction, his article (October 4, 2009) – Diverging Deficits Could Fracture the Eurozone – Münchau said “Germany … has committed itself to the virtuous path” – a moral valuation. What is virtuous about a particular ‘fiscal deficit’ outcome.

Similarly, in a Financial Times article (February 15, 2010) – Europe Cannot Afford to Rescue Greece – Otmar Issing claimed that Greece “wasted potential savings in a spending frenzy”.

This moral indignation to divert attention is common among German commentators. I could cite many examples. The practice is not, however, confined to Germany.

In his most recent intervention into the public debate (October 13, 2016) – Otmar Issing on why the euro ‘house of cards’ is set to collapse – Issing was discussing the so-called independence of the ECB and the allegations that it has been overly complicit with politicians in its quantitative easing program, which has seen it load its balance sheet up with fairly “low quality” debt instruments.”

8 Ingelesez: “He considered that the ECB had compromised its independence and had become a political tool of governments who realised that without ECB intervention their banking systems would collapse.

He spoke of the decision in May 2010 to bailout Greece.

By way of background, faced with nations unable to fund themselves but with pending liabilities maturing, the focus in 2010 turned to bailouts.

A new European bully formed, the so-called Troika (the European Union, the ECB and the IMF), to spearhead the austerity push.

Once again the unelected and unaccountable IMF felt its role was to trample on the democratic rights of citizens in Greece and elsewhere. While these interventions initially protected Greece and other nations from insolvency, they imposed destructive conditionality, which made it impossible for the nations under focus to grow.

On May 9, 2010, the European Council (through Ecofin) resolved to create the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), which would be its bailout vehicle in cooperation with the IMF. It was replaced in October 2012 by the permanent rescue vehicle, the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). Both institutions shared the same flaws.

The very idea of a bailout seemed at odds with Article 125 of the Treaty, the ‘no bailout’ clause. If the Treaty was so rubbery, why impose the SGP rules in the first place, given their severe negative consequences for economic growth and living standards?

Such inconsistencies among European policy makers were rife during the crisis as the ideologues that designed the rules, came against the reality of the system collapsing from the application of these rules. A desperate pragmatism reigned supreme but was so tainted by ideology (the unsustainable conditionality), that the bailouts just made matters worse.”

9 Ingelesez: “The first major bailout came in May 2010, when Greece was given a three year €110 billion loan from the Troika with strict conditions attached.

The austerity package was breathtaking in its harshness. Greece was compelled to reduce its deficit by 15 per cent of GDP within three years, which was an impossible task.

The terminology used by the IMF in its – Greece: Staff Report on Request for Stand-By Arrangement – was that the fiscal policy changes were:

… frontloaded with measures of 7½ percent of GDP in 2010, 4 percent of GDP in 2011, and 2 percent of GDP in 2012 and 2013, each, to turn around the fiscal position and help place the debt ratio on a downward path.

Remember, they claimed at the time that spending multipliers will below one, which justified their claim that the austerity would in actual fact stimulate growth. Two years later, the IMF admitted they had made fundamental errors in the calculations of the spending multipliers. Their revised conception indicated that these “frontloaded” measures would devastate the Greek economy – which they did.

It was also obvious that the austerity plan would, in fact, increase the deficits given the loss of tax revenue that would accompany the output and employment losses.

When announcing the terms of the bailout to the Greek people, Prime Minister George Papandreou wore a dark purple coloured tie, the colour that Greeks wear to funerals. But his days were numbered. Soon afterwards the Troika got rid of Papandreou and put one of ‘their men’ into the role, the central banker Lucas Papademos. It didn’t matter what the people who vote might think!

In that context, Issing reflected this week along the following lines:

It was clear over the weekend that if nothing happened by Monday, there might be turmoil in financial markets. It was obvious Greece could not meet its payments. Finance ministers were unable to deliver a solution. So the ECB was put in a lose-lose situation. By not intervening in the market, the ECB was at risk of being held responsible for a market collapse. But by intervening, it would violate its mandate by selectively buying government bonds — its actions would be a substitute for fiscal policy. The ECB had respectable arguments to intervene.

But it turned out that the ‘ECB had crossed the Rubicon.’ Of course, Julius Caesar had to go on and conquer Rome. But there was no need for the ECB to say that in the future in the same situation, it would act in a similar manner. It could have been made clear that this was a once-only event and would never happen again. Otherwise, it is a slippery road.”

10 Ingelesez: “The fact is that on 14 May 2010, the ECB established its Securities Markets Program (SMP), which saw it buying government bonds in the so-called secondary bond market in exchange for euros, which the ECB could create out of ‘thin air’. The SMP also permitted the ECB to buy private debt in both primary and secondary markets.

To understand this more fully, the decision meant that private bond investors (including private banks) could offload distressed state debt onto the ECB.

The action also meant that the ECB was able to control the yields on the debt because by pushing up the demand for the debt, its price rose and so the fixed interest rates attached to the debt fell as the face value increased. Competitive tenders then would ensure any further primary issues would be at the rate the ECB deemed appropriate (that is, low).”

11 Ingelesez: “There was hostility at the time from the Germans. For example, the fiscally conservative boss of the Bundesbank at the time, Axel Weber, who was being touted to replace Jean-Claude Trichet as head of the ECB, was vehemently opposed. He resigned his post as an ECB Board Member.

Weber’s successor as head of the Bundesbank, Jens Weidmann, maintained the criticism, albeit in a more muted manner.

Similarly, another ECB Executive Board member, Jürgen Stark, also resigned in protest over the SMP in November 2011. Stark told the Austrian daily Die Presse that the ECB was heading in the wrong direction by pushing aside the crucial no bailout clauses that provided the bedrock of the EMU.

He also said that the ECB had panicked by caving in to the pressure from outside of Europe.”

12 Ingelesez: “Whatever spin one wants to put on the SMP, it was unambiguously a fiscal bailout package.

The SMP amounted to the central bank ensuring that troubled governments could continue to function (albeit under the strain of austerity) rather than collapse into insolvency.

Whether it breached Article 123 is moot but largely irrelevant.

The SMP reality was that the ECB was bailing out governments by buying their debt and eliminating the risk of insolvency. The SMP demonstrated that the ECB was caught in a bind.

It repeatedly claimed that it was not responsible for resolving the crisis but at the same time, it realised that as the currency issuer, it was the only EMU institution that had the capacity to provide resolution.”

13 Ingelesez: “So while I agree with Issing that the ECB was put in that situation by the conduct of the Eurofin and European Commission in general, the fact remains that the SMP saved the Eurozone from breakup.

Without the SMP, Spain, Portugal, Ireland, Greece and a bit later Italy, would have become bankrupt given the movements in the private bond markets at the time.

The reality is that the flawed design of the Eurozone, which reflected the ideological hold of neo-liberalism on the integration discussions in the 1980s and beyond, meant that the only effective fiscal capacity in the currency union was held by the ECB.”

14 Ingelesez: “The Stability and Growth Pact constraints on fiscal policy and the bloody-minded approach adopted by the European Commission, particularly the Finance Ministers’ group (Eurofin), left the Member States impotent in the face of a major non-government spending collapse to defend their economies.

The flawed design of the Eurozone, which saw the Member States surrender their currency monopolies and adopt, what is in effect a foreign currency – the euro – meant that the Member States were dependent on the private bond markets for deficit funding.”

15 Ingelesez: “When those bond markets demanded increasingly higher spreads on the German bund to fund the peripheral economies who were devastated by a decline in aggregate spending and production, the only way out was for the ECB to use its currency capacity to resolve the crisis.

The Eurozone would have broken up in 2010 had not the ECB worked around the Article 123 restrictions by buying massive volumes of struggling government debt in the secondary markets.

It was not so much a reflection of political pressure, which implies there were options. Rather, at that time ECB was the only option, given the flawed nature of the Eurozone architecture.”

16 Ingelesez: “Issing also made some predictions in the interview. The question was asked: “How long can everything keep going before something gives? The politicians do not want to take action … So what happens next?”.

He replied:

Realistically, it will be a case of muddling through, struggling from one crisis to the next. It is difficult to forecast how long this will continue for, but it cannot go on endlessly. Governments will pile up more debt — and then one day, the house of cards will collapse.

In other words, the monetary union is built on fragile and untenable foundations.

Issing considered that the major problem was that:

The moral hazard is overwhelming …

This is a regular theme he indulges in.”

17 Ingelesez: “In his November 30, 2011 Financial Times article – Moral Hazard will result from ECB bond buying – Issing invoked the thoughts of Walter Bagehot (from his 1873 book Lombard Street), considered to be a founder of the concept of “the central bank as lender of last resort”.

Accordingly, any loans provided to the banking sector by the central bank should be a prohibitive rates to discourage the mentality that the central bank can always bail out poor commercial decisions.

Issing was not opposed to the ECB adopting a lender of last resort role (indeed he considered it an essential part of its operation). His point of contention was that the ECB was “offering unlimited liquidity to the banking system … on extremely low interest rates, not on a penalty rate”.

He argued in that article “that the central bank will be taken hostage by politics” if it acts “as the ultimate buyer of public debt”.

As a result:

Pressing the ECB into the role of ultimate buyer of public debt of individual member states would create the biggest conceivable moral hazard.”

18 Ingelesez: “In the current interview, he repeated the theme that the ECB had become captive of the political process.

The point he doesn’t make or, perhaps, even recognise, is that the entire creation of the monetary union was a political (ideological) artefact. It had no foundation in any reasonable understanding of monetary systems or economic processes like regional convergence etc.

It’s not that the politicians have taken over the situation and guided an otherwise sound monetary architecture into this desperate corner that it now finds itself in.

The architecture was tainted from day one by neo-liberalism.”

19 Ingelesez: “Had the founders of the Eurozone listened to the advice from those who understood how federal systems need to be constructed and operated they would not have created the Economic and Monetary Union, in the form that came out of Maastricht in the early 1990s.

They would have understood that the nature of the Member States that eventually became part of the monetary union were not commensurate with any reasonable notion of convergence. History, culture, language, economic structure and more militated against putting all these nations together in a common monetary arrangement.”

20 Ingelesez: “Further, no federal system can operate effectively without a federal fiscal capacity (spending and taxation), which is closely tied in with the currency capacity of the central bank.”

21 Ingelesez: “The problem is that the politicial processes since have had to become pragmatic to some extet to save the entire edifice from collapse.

The SMP was an example.

The treatment of French and German fiscal deficits in 2003 were examples.

The current way the European Commission has allowed Spain to violate the rules is another example.

The politicians know that the system they created is unworkable in its rigid form. Rules that are constantly quoted are also constantly ignored.”

22 Ingelesez: “Issing says that:

The Stability and Growth Pact has more or less failed. Market discipline is done away with by ECB interventions. So there is no fiscal control mechanism from markets or politics. This has all the elements to bring disaster for monetary union.

I agree that the Stability and Growth Pact has failed. It was neither a stability nor growth initiative. In fact, it was exactly the opposite. By constraining governments in their flexibility to respond to major spending collapses, the fiscal thresholds were unworkable.”

23 Ingelesez: “As we have seen, enforcing the rules made matters worse. They had to be broken or the system would have already collapsed.

The problem has been that they have been enforced or relaxed in a non-systematic manner, which has, in effect, exacerbated the crisis. In the case of Greece, the enforcement has devastated that nation. In the case of Spain, the relaxation of the rules allowed the economy to grow again, but has had the effect (planned) of propping up an austerity-biased Conservative government.

Further, if the private bond markets had been allowed to dominate, then as noted above, the monetary union would have collapsed in 2010.”

24 Ingelesez: “Issing said that:

The ECB is now buying corporate bonds that are close to junk, and the haircuts can barely deal with a one-notch credit downgrade … The decline in the quality of eligible collateral is a grave problem. The reputational risk of such actions by a central bank would have been unthinkable in the past.

This apparently, in his own words, put the ECB on a “slippery slope” because much of this debt will generate ‘losses’ for the bank.

However, this is not what I would call a “grave problem”. The ECB would be well advised to write all of that debt off immediately. There would be very little consequence of it doing so.

The problem, in the first place, was a lack of oversight of the private banking sector as it fuelled a debt binge in the pre-crisis period.”

25 Ingelesez: “Issing also believes that talk of political union is wasted because it is not a possibility. I agree that the Member States are so different in history and culture etc that they will never surrender political autonomy in the same way they surrendered their currency autonomy.

In that sense, the basic flaws in the monetary union are beyond political solution.”

26 Ingelesez: “But unlike me, who considers the creation of such a federal fiscal capacity is an essential requirement, and, in its absence, the Eurozone must break up, Issing maintains the view that:

Such a system would erode the budgetary sovereignty of the member states and violate the principle of no taxation without representation.

That is the issue. If the Member States want to retain “budgetary sovereignty” then they have to retain their currency sovereignty.

That means the monetary union collapses. The only other option is to create a true federal fiscal capacity grounded in a democratic institution such as the European Parliament to be consistent with the “the principle of no taxation without representation”

That option is not going to happen.”

27 Ingelesez: “I agree with Issing that what has emerged is a system that is inherently recessive and deflationary.”

28 Ingelesez: “Mass unemployment is the norm and increasing poverty the outcome.”

29 Ingelesez: “As a result, political processes are moving increasingly towards the extreme.”

30 Ingelesez: “An orderly breakup is the best way forward now.”

joseba says:

EBZ: bide guztiak helmuga berberera

Bill Mitchell-en ECB – every which way but to the point ( http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=34706)

(…)

QE has been a failure

(…)

First, monetary policy is a very weak counter-cyclical tool (that is, a policy tool that can work against the non-government sector spending cycle).

(…)

It was believed that the ECB (and any central bank engaging in the practice) would immediately stimulate bank lending by giving them more reserves via the QE asset swap (reserves for bonds).

This has been core neo-liberal theory – that bank lending is constrained by reserve availability.

As I explained in this blog (early on in the saga) – Quantitative easing 101 – and later in the following blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – bank lending is never so constrained.

Banks do not lend reserves other than between themselves to cover shortfalls in the payment system (cheque clearing) requirements on day-to-day basis.

Banks lend when there are credit-worthy customers willing to borrow and then manage their reserve positions after the fact to ensure they retain integrity within the payments system.

The reason that credit access was so low in the aftermath of the GFC was that no one was willing to take on the risk of borrowing when economic activity was weak.

(…)

… the so-called sovereign debt crisis in the Eurozone was just a symptom of the flawed design of the Eurozone and the willingness of the monetary authority to selectively violate the Treaty provisions when it was ideologically consistent to do so.

In other words, the ECB was quite willing in May 2010 to use its currency-issuing capacity to deal the private bond markets out of the game. The central bank quickly resolved the diverging Member State bond yield spreads (relative to the German bund) and when it did, under the aegis of the Securities Markets Program (SMP), the diverging yield spreads were quickly stabilised.

In effect, the ECB was, via its secondary bond market purchases, acting as a fiscal agent, in lieu of such a authority being created under the Treaty of Maastricht.

The problem was that the ECB went into partnership with the European Commission and the IMF (the so-called Troika) and in return for stabilising the bond yield spreads it insisted that Member States undertake pernicious austerity policies that undermined any prospect of economic growth.

It wasn’t the diverging bond yield spreads that cause the problem, as the ECB author would like us to believe. Rather, it was the fiscal austerity that was imposed that caused the problem.

There was no sovereign debt crisis in the Eurozone once the ECB indicated its intentions under the Securities Markets Program and its subsequent iterations.

(…)

As explained above, the ECB dealt with the diverging bond yield spreads once said introduced the SMP. There was no sovereign debt crisis after that point as long as the ECB maintained that program.

The so-called “tighter fiscal policies” (an understatement if there was ever one) were imposed as part of the enforcement mechanisms under the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP).

While the SGP has historically been applied in an inconsistent way (remember the French and German let off in 2003), the imposition of austerity on nations such as Greece, Portugal, Spain in 2010 and onwards was not to protect private bond markets, but rather, to maintain the ideological hegemony of an intrinsically neo-liberal European Commission.

The recession that followed was created by the austerity. Once the ECB demonstrated it could use its currency-issuing capacity to purchase any volumes and type of government debt if desired, the so-called ‘sovereign debt crisis’ became a non-issue.

(…)

I don’t think the ECB policy is doing anything to stimulate either component of aggregate spending.

I think the Eurozone is being starved of confidence and hence private spending growth by the fiscal policy regime that the European Commission is dictating – as if it is mandated under the Treaty.

The inconsistency of the Commission’s approach is highlighted by the way it has allowed Spain, for example, to grossly violate the fiscal rules to allow that nation to resume growth and offset political forces that would unseat the PP conservatives.

The whole Eurozone reality is a mess and will not improve significantly until the Treaties are abandoned and currency sovereignty is restored to the Member States.”

joseba says:

Gehigarria:

“The eurozone is turning into a poverty machine”

(http://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2016/10/24/the-eurozone-is-turning-into-a-poverty-machine/)

“There are constant bank runs. The bond markets panic, and governments along its southern perimeter need bail-outs every few years. Unemployment has sky-rocketed and growth remains sluggish, no matter how many hundreds of billions of printed money the European Central Bank throws at the economy.

We are all tediously aware of how the euro-zone has been a financial disaster. But it is now starting to become clear that it is a social disaster as well. What often gets lost in the discussion of growth rates, bail-outs and banking harmonisation is that the eurozone is turning into a poverty machine.

As its economy stagnates, millions of people are falling into genuine hardship. Whether it is measured on a relative or absolute basis, rates of poverty have soared across Europe, with the worst results found in the area covered by the single currency.

There could not be a more shocking indictment of the currency’s failure, or a more potent reminder that living standards will only improve once the euro is either radically reformed or taken apart.

Eurostat, the statistical agency of the European Union, has published its latest findings on the numbers of people “at risk of poverty or social exclusion”, comparing 2008 and 2015. Across the 28 members, five countries saw really significant rises compared with the year of the financial crash. In Greece, 35.7pc of people now fall into that category, compared with 28.1pc back in 2008, a rise of 7.6 percentage points. Cyprus was up by 5.6 points, with 28.7pc of people now categorised as poor. Spain was up 4.8 points, Italy up 3.2 points and even Luxembourg, hardly known for being at risk of deprivation, up three points at 18.5pc.

(…)

It gets worse. “At risk of poverty” is defined as living on less than 60pc of the national median income. But that median income has itself fallen over the last seven years, because most countries inside the eurozone have yet to recover from the crash. In Greece, the median income has dropped from 10,800 euros a year to 7,500 now. In Spain it has not been quite so dramatic, but median income has still gone down from 13,996 euros a year to 13,352. In reality, people are getting both relatively and absolutely poorer.

There are other measures that make that clear as well. Across the EU, 8pc of people are defined as “severely materially deprived”, which means that they lack access to what most civilised societies regards as basic necessities – if you tick four out of nine boxes, which include not being able to afford to heat your home, eat meat or fish or a similar protein at least every other day, or pay for a phone, then you fall into that category.

Strikingly, several eurozone countries are now starting to lead on those measures. Greece, inevitably, is rising fast, with 22pc of the population now falling into that category, compared with only 11pc back in 2008. In Italy, a country that was as prosperous as any in the world two decades ago, a shocking 11pc of the population are now “materially deprived” compared with 7.5pc seven years ago. In Spain the rate has doubled, and in Cyprus it is up by more than 50pc.

(…)

It is hard to think of any other plausible explanation for the stark difference between poverty rates for the countries inside and outside the eurozone. Why should Greece and Spain be doing so much worse than anywhere in Eastern Europe? Or why Italy should be doing so much worse than Britain, when the two countries were at broadly similar levels of wealth in the Nineties? (Indeed, the Italians actually overtook us for a while in GDP per capita.) Even a traditionally very successful economy such as the Netherlands, which has not been caught up in any kind of financial crisis, has seen big increases in both relative and absolute poverty.

In fact, it is not very hard to work out what has happened. First, a dysfunctional currency system has choked off economic growth, driving unemployment up to previously unbelievable levels. After countries went bankrupt and had to be bailed out, the EU, along with the ECB and the IMF, imposed austerity packages that slashed welfare systems and cut pensions. It is not surprising poverty is increasing under those conditions.

In the financial markets, there is an endless focus on the state of the banking system within the eurozone, on rising budget deficits, and on the risk of deflation and the havoc it might play on asset prices. But in the end, the financial crisis does not matter that much. It can be fixed with bail-outs and by printing more money. Even if it can’t, it just means some banks and investment funds will be worse off.

But the fact that poverty levels are rising so fast in what were prosperous countries is shocking. There is no sign of that rise slowing down – indeed, in countries such as Greece and Italy, it is accelerating. What were once dirt-poor countries, such as Bulgaria, or middle income countries like Poland, are fast over-taking what used to be developed Europe.

Not being able to afford a phone, or to eat meat three times a week, is no fun. But thanks to the euro that is now the fate of millions of Europeans – and it will not change until the currency is taken apart.”