(i) Eskudiruarekin ordaindutako zergak

Ulertuko dugu afera hori inoiz?

Angela Walch(e)k Bertxiotua Old Pics Archive

Amazing pics. A sign of the loss of faith in the government & the nation/community itself. #money #hyperinflation @dgwbirch

Angela Walch(e)k gehitu du,

Old Pics Archive @oldpicsarchive

Cash prepared for burning, Germany 1923 / Hyperinflation in Germany, 1923 http://bit.ly/2cywoG6

2016 urr. 2

@angela_walch Oh yeah, “loss of faith in the government & the nation/community itself”; not about large debts payable in gold. &c @dgwbirch

@GrkStav Of course, having impossible-to-pay debts contributes greatly to the loss of faith. @dgwbirch

@angela_walch And the ones to whom your country owes those debts sending troops to occupy your industrial heartland . . . @dgwbirch

Warren B. Mosler @wbmosler urr. 3

@angela_walch @tymoignee @dgwbirch @oldpicsarchive And if you buy US gov bonds or pay taxes with old cash they have it shredded.

Eric Tymoigne @tymoignee urr. 3

@wbmosler @angela_walch @dgwbirch @oldpicsarchive And then it is used mostly as compost (really).

FerdinandoنAmetrano @Ferdinando1970 urr. 3

@angela_walch @dgwbirch @oldpicsarchive shredded dollars, given away as gadget at #Sibos2016

(ii) Etorkizuneko LANA

Pavlina R Tcherneva @ptcherneva2

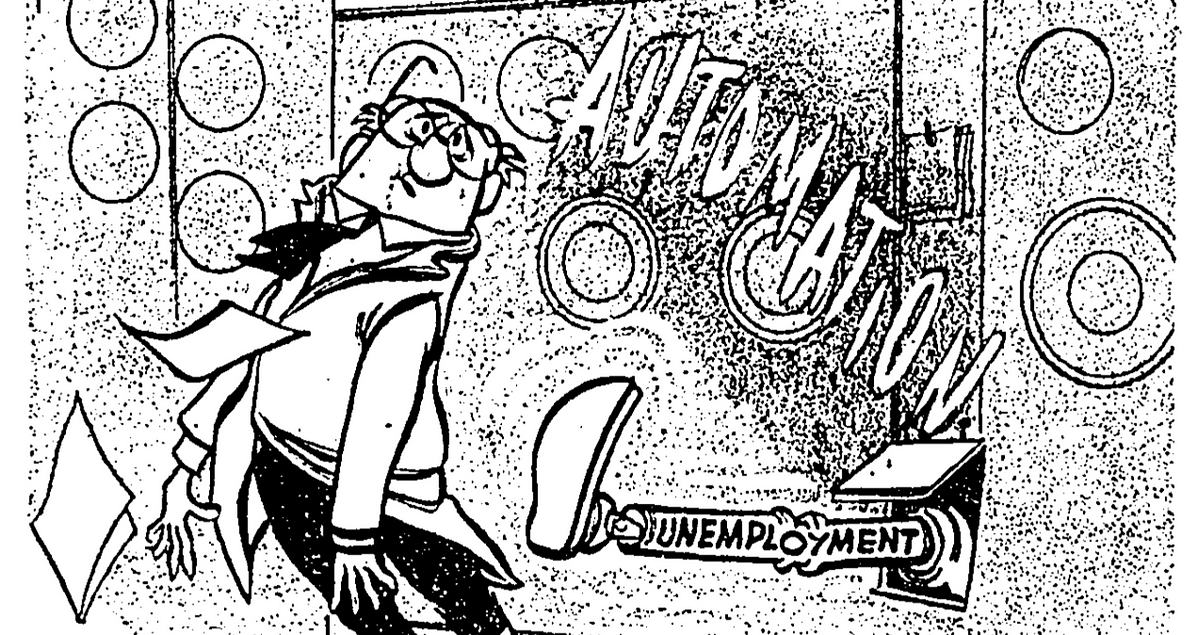

90% of the jobs of the future have not been created yet, but unemployment will remain a unique challenge

Robots have been about to take all the jobs for more than 200 years3

Is it really different this time?

2016 urr. 4

(iii) Deutsche Bank: konfidentziaren krisia

Will the Crisis of Confidence at Deutsche Bank Spread?4

“(…) Not Like Lehman Bros.

As for concerns that Deutsche Bank is facing a demise similar to Lehman Bros. in the financial crisis, Wharton finance professor Itay Goldstein points to significant differences. “It is certainly alarming to see a big bank like Deutsche Bank run into such problems. However, there is no indication at this point that this will be as big a crisis as the one surrounding the Lehman collapse back in 2008,” he says. Goldstein also points out that the environment has changed: The global financial system is better prepared now, having learned from the interconnections that led to the financial crisis.

“Deutsche Bank is in better shape when it comes to liquidity, and is not yet close to the point Lehman was in of being completely cash-starved. Second, the problems with Lehman came due to the fact that it had many complex interconnections throughout the financial system, which many did not understand until things got worse,” Goldstein says. Also, “the decision to let Lehman fall is now seen as having backfired, since it led to the big crisis. I suspect governments will now be more risk-averse before letting something like this happen and consider more the idea of helping Deutsche Bank.”

However, Goldstein says German officials might be politically hamstrung from mounting a rescue. They have a strict policy against bailouts and “were very explicit about this in issues that arose with Italian banks recently. So, it will be hard for them to change the tone now and come to the rescue of their own banks,” he says. Whatever action the German government takes, Goldstein believes one thing is clear: “It does not seem at the moment like this will become the next Lehman crisis.”

But investors remain concerned. Deutsche Bank shares trade for around a quarter of its book value, which is “unusual and a sign of investor worry,” notes Wharton finance processor Krista Schwarz. Some hedge funds were concerned enough that they pulled accounts and trading business from the bank — the same type of liquidity squeeze that felled Lehman.

Still, “I don’t think that this is going to be a repeat of Lehman,” Schwarz says. “Deutsche Bank is a still-solvent bank that is facing liquidity problems. People will argue for a long time to come whether Lehman was truly insolvent, but it is uncontroversial to say that Lehman was very close to the borderline of insolvency. (…)”

(iv) Feminismo fiskala

Fiscal Feminism: Pavlina R. Tcherneva5

“This week, we are joined by economist and professor Pavlina R. Tcherneva, who says the current practice of gender-blind and race-blind fiscal policy lacks visions and helps no one. Congress, according to Tcherneva is focusing on the wrong things. A self ascribed feminist economist, Tcherneva says feminist fiscal policy is real, not simply ideological, and should be a central part of the American economy. We’ll encourage growth, she says, by creating employment — not the opposite. And employment begins with targeting women and racial minorities as the benefactors of policy.”

(v) Zergatik aberatsak zergapetzea? Ez dugu behar haien dirua!

Why Tax the Rich if We Don’t Need Their Money?6

“Congress does not need to get money from rich people in order to fulfil its responsibility to do what is in the public’s interest. This does not mean we shouldn’t raise taxes on the wealthiest Americans, but rather that we should do so for the right reasons; and there are many good reasons. Fundraising for the Treasury just isn’t one of them. Congress is never constrained by the amount of taxes received. So when we raise federal taxes on those with high incomes it should be either to help maintain a strong currency or because doing so serves some benefit to the economy or society – i.e. public purpose and general welfare. More on this in a moment.

Our collective failure to understand this distinction is undermining our ability to utilize fiscal policy appropriately for the general well being of our nation and the long term health of our economy. It is essential that we regain a proper understanding of our currency in order to avoid the kind of disastrous bi-partisan policy-making that stems from a misguided linkage of federal taxation and federal spending.

(…)

The federal government creates US Dollars when it spends and removes US Dollars when it taxes. (…) Our government is not revenue-constrained and Congress knows it. (…)

(…) the right way to run a sovereign currency:

- first establish what is in the public interest via the democratic process and authorize the spending;

- second, establish the appropriate level of taxation to maintain currency stability and full employment.

(…)

A sovereign currency means everything

Now before I go too far, it is important to draw a clear distinction between a currency-issuer and all other economic entities, whether governments or businesses or households. This distinction is what helps us redefine the purpose of federal taxation.

A truly sovereign nation is one that:

- issues its own currency,

- allows the value of their currency to float in exchange with other currencies,

- makes no promise of rigid convertibility (such as to gold or another currency at a fixed price), and

- does not have debt denominated in a foreign currency.

By definition, the currency issuer must spend or lend its money into the economy before we can obtain it to pay our taxes. US Dollars can only come from the issuer of US Dollars – other sources are counterfeit. And by definition, such a nation cannot become insolvent or default, unless by choice, since it “owes” only that money which it creates on demand.

Countries that lose any one of these criteria have imposed restrictions on their ability to use fiscal policy in the national interest and for the good of their people. For example, countries in the Eurozone (including Portugal, Ireland and Greece) gave up full monetary sovereignty. They have become like currency-using states. Their governments must tax or borrow Euros in order to spend them. Now you can begin to understand why Japan has no sovereign debt crisis while Greece does.

(…) Unfortunately, like those in Galileo’s time who thought the sun went around the earth, we’ve been looking at the process of national currencies the wrong way. This is in part a vestige of a bygone era of fixed exchange rates and gold convertibility (refer to the limiting criteria mentioned above).

(…)

Why tax the rich if we don’t need their money?

If taxation at the federal level simply removes some of the government’s currency back out of the economy after it first spent or credited it into existence, why do we need to tax at all?

I find it helpful to separate the purpose of currency taxation into two broad categories: i) maintaining a useful currency, and ii) achieving public purpose (which of course includes a healthy economy and stable currency).

1. Taxes drive the currency

(…)

Economist Abba Lerner, who coined the term “Functional Finance”, wrote the following during WWII about how our currency should be managed:

The first financial responsibility of the government (since nobody else can undertake that responsibility) is to keep the total rate of spending in the country on goods and services neither greater nor less than that rate which at the current prices would buy all the goods that it is possible to produce. If total spending is allowed to go above this there will be inflation, and if it is allowed to go below this there will be unemployment.

(…)

This approach makes a lot of sense and we should work to further improve such policies. A federally funded job guarantee to support full employment at all times would be a complimentary spending approach to further help stabilize the currency and the economy.

(…) the essential point is that some amount of taxes are required to create acceptance of the government’s currency and to help regulate the economy. A combination of tax policies would do this job effectively, and taxing high income earnings at higher rates should be part of that mix.

2. Taxes express public policy

This is where we really need to focus our attention if we are to make any headway in addressing the growing inequity in our society. Misguided arguments that the wealthy should “pay for” federal programs only serve to give more power to the wealthy over our government policymakers, artificially restricting spending for public good until tax concessions can be obtained from them. The government doesn’t need their money in order to spend. However, high income earners should absolutely be taxed and disproportionately so.

There are vital social, economic, and democratic reasons to prevent excessive accumulation of wealth, shape the distribution of incomes, and encourage the kind of economic behavior that promotes sustainable prosperity for all.

Taxation reduces spendable income and influences economic behavior. As such, it is a tool to express public policy and should be designed to achieve a given public purpose, not as a source of funds for the Treasury. Once the mistaken “pay for” rationale has been removed we can focus on what taxes really do for us. For example, we can:

-

tax wages if there is a good reason to lower the spendable income of wage earners;

-

tax income at different tiers if there is a good reason to shape the distribution of incomes;

-

tax profits if there is a good reason to reduce profits;

-

tax some products more than others if there is a good reason to make some products more expensive or discourage their production or consumption.

With this in mind, we can begin to rationalize the public purpose for increased taxation on the upper end of society. Note that we have moved the debate away from what the rich should pay for and toward a conversation about the kind of country and economy we want. For example:

-

Are growing wealth dynasties unhealthy for democracy?

-

Does our economy need less debt-fueled speculative investing and more consumption-driven growth?

-

Are executive compensation packages and corporate finance practices supporting long term sustainable growth and value for all stakeholders?

-

Do billionaires and corporations have an unhealthy influence over the legislative, judicial and executive branches of our government?

-

Are wealthy interests controlling, exploiting or otherwise harming our ecological systems that are essential for our long term health and prosperity?

-

Do low- and average-income workers have enough take-home pay to live well or are their incomes too small and taxes too high?

-

Is finance being used primarily to serve the productive economy and public needs or is it undermining long term economic growth and societal well being?

These are just a few questions to start our public discourse and many of you will have important contributions to make in your respective fields. Tax policy clearly can’t do everything. We have significant investment opportunities throughout our nation that could serve to greatly improve the quality of life for many people and set a path for our nation’s future prosperity. We can and should be working in parallel to increase funding for such initiatives while also addressing tax reforms that will serve to strengthen our democracy and economy, including ending tax favoritism for investors. Congress needs to sever the link between taxation and spending, and start redesigning fiscal policy – both spending and taxing – in ways that serves to increase the general welfare of all Americans.”