Bill Mitchell-en Helicopter money is a fiscal operation and is not inherently inflationary1

Sarrera: Inflazioaz2

(i) Zer ote da helikoptero dirua3

UEU-ko blogean aritu gara afera horretaz, ikus, kasu, ondoko linkak:

Pavlina Tcherneva: Joerg Bibow-ek helikoptero diruaz

Politika monetarioa efektiboa izateko, batera lan egin behar du politika fiskalarekin

(ii) DTM eta helikoptero dirua4

(iii) Politika fiskala: defizit fiskala5

(iv) Zergapetzea, erreserbak, bonoak eta zor publikoa: altxor publikoa eta banku zentrala6

(v) Zer ote da QE7

(vi) Milton Friedman-en helikopteroa eta DTM-ren Overt Monetary Financing (OMF)8

(vii) Japonia, OMF eta inflazioa9

(viii) Urre estandarra abandonatzearen ondorioak10

(ix) Grafikoa11

(x) Weimar, Zimbabwe: hyper-inflazioa12

(xi) Benetako afera: inflazioa nola ulertzen den13

(Segituko du)

2 Ingelesez: “(…) If a government continues to increase nominal spending growth ahead of the growth in productive capacity then there will be inflation. The argument presented is, in fact, nothing to do with the monetary operations that accompany government spending – helicopter or otherwise. The inflation risk is in the spending. If private investment expenditure outstripped the capacity of the supply-side to produce the capital equipment demanded then the same outcome. Should we caution against such expenditure? Should be make it taboo? Obviously not.”

3 Ingelesez: “What is helicopter money?

I have discussed helicopter money previously:

1. Keep the helicopters on their pads and just spend.

2. Overt Monetary Financing would flush out the ideological disdain for fiscal policy.

4 Ingelesez: “From the perspective of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), a helicopter drop is equivalent to an increase in the fiscal deficit in the sense that new financial assets are created and the net worth of the non-government sector increases.

It occurs when the government uses its currency-issuing capacity (linking treasury spending to central bank operations) without matching its deficit spending with debt-issues to the non-government sector.

So the central bank adds some numbers to the treasury’s bank account to match its spending plans and in return may be given treasury bonds to an equivalent value.

Instead of selling debt to the private sector, the treasury simply sells it to the central bank, which then creates new funds in return.

This accounting smokescreen is, of course, unnecessary. The central bank doesn’t need the offsetting asset (government debt) given that it creates the currency ‘out of thin air’. So the swapping of public debt for account credits is just an accounting convention.”

5 Ingelesez: “To understand the consequences of this policy choice, ask the question, what would happen if a sovereign, currency-issuing government (with a flexible exchange rate) increased its fiscal deficit without issuing the matching $ in debt to the non-government sector?

First, governments spend in the same way irrespective of the monetary operations that might follow. There is no sense in the claim that the government gathers money from taxes or bond sales in order to spend it.

If they didn’t issue new debt to match the increase in their deficit, then like all government spending, the treasury would instruct the central bank to credit the reserve accounts held by the commercial bank at the central bank. The commercial bank in question would be where the target of the spending had an account. So the commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a deposit would be made.

The transactions are clear: The commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a new deposit has been made. Further, the target of the fiscal initiative enjoys increased assets (bank deposit) and net worth (a liability/equity entry on their balance sheet).”

6 Ingelesez: “Taxation does the opposite and so a deficit (spending greater than taxation) means that reserves increase and private net worth increases.

This means that there are likely to be excess reserves in the ‘cash system’ (bank liquidity) which then raises issues for the central bank about its liquidity management. The aim of the central bank is to ‘hit’ a target interest rate and so it has to ensure that competitive forces in the interbank market (where banks loan reserves to each other) do not compromise that target.

When there are excess reserves there is downward pressure on the overnight interest rate (as banks scurry to seek interest-earning opportunities), the central bank then has to sell government bonds to the banks to soak the excess up and maintain liquidity at a level consistent with the target.

The alternative is that the central bank can offer a return on overnight reserves which reduces the need to sell debt as a liquidity management operation.

There is no sense that these debt sales have anything to do with ‘financing’ government net spending. The sales are a monetary operation aimed at interest-rate maintenance. So the monetary measure – M1 (deposits in the non-government sector) – rise as a result of the rise in the fiscal deficit without a corresponding increase in liabilities. It is this result that leads to the conclusion that that deficits increase net financial assets in the non-government sector.

So when the government matches its deficit spending with debt-issuance to the non-government sector it is really only altering the composition of the wealth portfolio of the non-government sector. It swaps bonds for bank deposits essentially.

What would happen if there were bond sales to the non-government sector? All that happens is that the banks reserves are reduced by the bond sales but this does not reduce the deposits created by the net spending. So net worth is not altered. What is changed is the composition of the asset portfolio held in the non-government sector.

The only difference between the Treasury ‘borrowing from the central bank’ and issuing debt to the private sector is that the central bank has to use different operations to pursue its policy interest rate target.

If private debt is not issued to match the deficit then it has to either pay interest on excess reserves (which most central banks are doing now anyway) or let the target rate fall to zero (the long-time Bank of Japan solution).

There is no difference to the impact of the deficits on net worth in the non-government sector.”

7 Ingelesez: “… Michael Heise (The Unavoidable Costs of Helicopter Money) clearly misunderstands what a helicopter drop is.

He writes:

In practice, helicopter money can look a lot like quantitative easing – purchases by central banks of government securities on secondary markets to inject liquidity into the banking system.

In fact, the helicopter option is not akin to quantitative easing – that is a common misperception.

QE is a monetary operation that is nothing more than the central bank swapping bank reserves (central bank money) with bonds (or other financial assets) held by the non-government sector.

It was introduced on the false premise that banks were not lending because they had insufficient reserves. Cure? Boost their reserves. How? Use central bank money which is in inexhaustible supply to buy bonds held by the banks in return for reserves. QED! Right?

Wrong! Even the mainstream economists must surely be catching on by now that banks do no need reserves to lend. They worry about reserves after the fact and know they can always get them from the central bank anyway, who operates to prevent financial instability, which might include large scale defaults within the payments system (that is, cheques bouncing because banks didn’t have the reserves to back the loans they had issued).

The only way QE could boost economic activity was because it reduced longer interest rates (because it increased the demand for longer-term bonds and drove down their yields). However, this mechanism also didn’t work because the state of sentiment has been so poor that households and firms have been reluctant to borrow no matter how cheap the loans might have become.

The helicopter option is a fiscal intervention which injects new net financial assets into the non-government sector and directly stimulates aggregate spending.

There is a world of difference between the two actions.

Further, whether governments issue debt to the non-government sector or not, there is no difference in the inflation risk of the deficit spending.”

8 Ingelesez: “Michael Heise falls into the mainstream trap by assuming increases in bank reserves are inflationary.

He links a helicopter drop to Milton Friedman and then tries to invoke the standard Monetarist line with respect to inflation:

As Milton Friedman often said, in economics, there is no such thing as a free lunch.

In historical terms, Milton Friedman introduced the terminology of a ‘helicopter drop’ into the literature. The association is flawed.

In his 1948 article by Milton Friedman wrote (p.5):

… government expenditures would be financed entirely by tax revenues or the creation of money, that is, the use of non-interest bearing securities. Government would not issue interest bearing securities to the public.

[Reference: Friedman, M. (1948) ‘A Monetary and Fiscal Framework for Economic Stability’, American Economic Review, 38, June, 245–64.]

But while it might give progressives strength to argue for what is essentially Overt Monetary Financing (OMF) because even the arch free market economist supported the approach, the reality is somewhat different.

Friedman’s proposals were part of what was known as the Chicago Plan (emanating out of the free market bastion at the University of Chicago), which proposed a broad regime change where private banks would be prevented from creating new money and public deficits would be the only source of new money.

Equally, the government would run a balanced fiscal position over the cycle and destroy the money created in the downturn when they ran offsetting surpluses in the upturn.

This is a very different proposition to the MMT (and other) suggestions for OMF to become part of a bringing together of monetary and fiscal policy to stimulate economic activity.”

9 Ingelesez:“Michael Heise thinks that OMF (helicopter money) would be inflationary:

In fact, there are major downsides to helicopter money. Most important, by enabling the monetization of unlimited amounts of government debt, the policy would undermine the credibility of the authorities’ targets for price stability and a stable financial system. This is not a risk, but a certainty, as historical experience with war finance – including, incidentally, in Japan – demonstrates only too clearly.

He is referring to the intervention in Japan by its “Finance Minister Takahashi Korekiyo” in the early 1930s as a means of heading off the Great Depression.

I discussed that in detail in this blog – Takahashi Korekiyo was before Keynes and saved Japan from the Great Depression.

Michael Heise claims that the stimulus from Takahashi Korekiyo’s helicopter drop generated “a powerful wave of inflation”.

But his historical recall is poor.

There were three notable sources of stimulus introduced by Takahashi Korekiyo:

1. The exchange rate was devalued by 60 per cent against the US dollar and 44 per cent against the British pound after Japan came off the Gold Standard in December 1931. The devaluation occurred between December 1931 and November 1932. The Bank of Japan then stabilised the parity after April 1933.

2. He introduced an enlarged fiscal stimulus. In March 1932, Takahashi suggested a policy where the Bank of Japan would underwrite the government bonds (that is, credit relevant bank accounts to facilitate government spending).

This proposal was passed by the Diet on June 18, 1932. The Diet passed the government’s fiscal policy strategy for the next 12 months with a rising fiscal deficit 100 per cent funded by credit from the Bank of Japan.

Bank of Japan historian Masato Shizume wrote in his Bank of Japan Review article (May 2009) – The Japanese Economy during the Interwar Period: Instability in the Financial System and the Ipact of the World Depression – that:

Japan recorded much larger fiscal deficits than the other countries throughout Takahashi’s term as Finance Minister in the 1930s.

On November 25, 1932, the Bank of Japan started ‘underwriting’ the government’s spending.

3. The Bank of Japan eased interest rates several times in 1932 (March, June and August) and again in early 1933. This easing followed the cuts by the Bank of England and the Federal Reserve Bank in the US. Monetary policy cuts were thus common to each but the size of the fiscal policy stimulus was unique to Japan.

[Reference: Shizume, Masato (2009) “The Japanese Economy during the Interwar Period: Instability in the Financial System and the Impact of the World Depression”, Bank of Japan Review, 2009-E-2]]

What followed is clear:

1. Real GDP growth returned quickly and stood out by comparison with the rest of the world which was mired in recession. Between 1932 and 1936, real industrial production grew by a staggering 62 per cent.

2. Employment, which had also plummeted in the early days of the Great Depression, grew robustly after the Takahashi intervention.

3. Inflation spiked as a result of the exchange rate depreciation in 1933 but quickly fell to low and relatively stable levels in 1934 as the economy’s growth rate picked up under the support of the fiscal and monetary stimulus.”

10 Ingelesez: “It was clear that abandoning the Gold Standard was a crucial first step because it gave the government space to introduce major domestic stimulus policies. These policies were not possible under the Gold Standard because they would have pushed out the external deficit and the nation would have lost its gold stocks.”

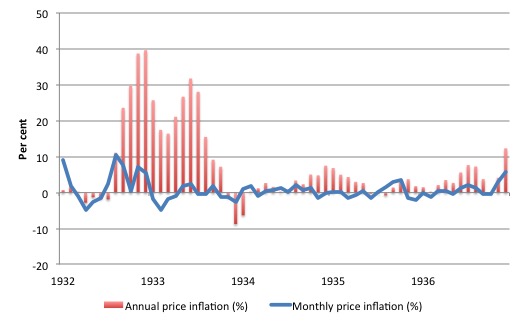

11 Ingelesez: “The following graph uses price data from the Bank of Japan to show the annual and monthly inflation between January 1932 and December 1936 in Japan.

The fiscal stimulus continued well beyond inflation spike, which was largely due to the exchange rate depreciation engineered by the Bank of Japan.

To claim that the OMF policy adopted by the Japanese government led to “a powerful wave of inflation” is false.”

12 Ingelesez: “Michael Heise also reprises the Weimar scare story.

Hyperinflation examples such as 1920s Germany and modern-day Zimbabwe do not support the claim that fiscal deficits cause inflation.

In both cases, there were major reductions in the supply capacity of the economy prior to the inflation episode.

Those examples provided very little guidance on what would happen to a modern state which abandoned matching fiscal deficits with debt issuance to the non-government sector as noted above.

There is a dishonesty in journalism that keeps throwing those examples up without informing the reader of what actually happened in each case.

Please read my blog – Zimbabwe for hyperventilators 101 – for more discussion on this point.”

13 Ingelesez: “But we soon get to the nub of the story – which reveals the incongruity of his argument.

He says that it would be politically difficult to rein in government spending under OMF:

The truth is that the central bank would struggle to defend its independence once the taboo of monetary financing of government debt was violated. Policymakers would pressure it to continue serving up growth for free, particularly in the run-up to elections …

The problem, which Friedman identified in 1969, is that while helicopter money generates more demand in an economy, it does not create more supply. So the continued provision of helicopter money after an economy has returned to normal capacity utilization – the point at which demand and supply are in equilibrium – will cause inflation to take off.

So there you see the concern in a nutshell.

First, he believes we cannot trust our elected representatives. So it is better to constrain them with voluntary rules and straitjackets, which then create mass unemployment and low growth.

I find that argument ridiculous. The ballot box constrains politicians. And progressives have to also work hard to improve governance and oversight.

Second, you see that he is confusing the monetary and fiscal operations (spending with no debt issuance) with the inflation risk inherent in spending.

No-one who advocates OMF is suggesting that a government would continue expanding nominal spending via ever-growing deficits once an economy had reached full capacity and full employment. It is obvious that if such a strategy was pursued then ever-increasing inflation would be the result.

This is because firms cannot squeeze any more real output out of the resources in use.

Alternatively, when there are idle resources (such as unemployed labour and machines), an expansion of nominal spending will likely be mostly absorbed by higher production (real output) and firms will be highly reluctant to try to increase prices for fear of losing market share to other firms in the sector.

Most importantly, growth in nominal spending can continue even when the economy is operating at full capacity as long as it matches the growth in that productive capacity and doesn’t strain the capacity of the economy to respond to the extra spending with output growth.

So it is false to claim that ‘helicopter money’ (OMF) after full employment is reached becomes inflationary. It does not if the supply side expands in proportion.

Once you understand that it is the spending growth that carries the inflation risk rather than the monetary operations that might accompany that growth, you realise that commentators like Micheal Weise really do not grasp the essentials of the monetary system they claim expertise over.

He conflates the monetary gymnastics with the spending and thinks it is the former that is the inflation risk.

As noted above, the inflation risk is not reduced if governments sell debt to match the increase in their deficit or not.

A simple way of thinking about it is that the cash to buy the bonds issued by the government was not being spent anyway. The bond sale just offers the non-government sector a chance to swap a non-interest bearing financial asset for an interest-bearing asset (a swap within the saving or wealth portfolio).”