Bill Mitchell-en Time for fiscal policy as we learn more about monetary policy ineffectiveness1

(i) Japonia eta Australia: diferentziak2

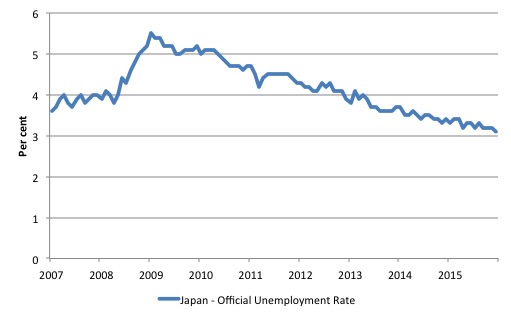

Here is a graph of the Japanese unemployment rate from July 2007 to June 20163.

(ii) Japonia eredua4

(iii) Eurogunean ez da hori gertatu5

(iv) Australian ere ez6

(v) Norvegiako Axel Leijonhufvud ekonomialaria 1968an politika monetarioaz eta fiskalaz7

(vi) Politika monetarioari buruzko gaur egungo eztabaida8

(vii) Depresio Handia eta Keynes9

(viii) Marriner Eccles eta politika monetarioa10

(ix) Great Financial Crisis delakoa eta politika fiskala11

(x) Australia eta politika fiskala12

(xi) Australiaren Altxor Publikoaren konklusioak politika fiskalaren alde13

Ondorio orokorrak

(a) Japonia eredua14

(b) Australiak egin beharko lukeena15

2 Ingelesez: “The week before last, the Bank of Japan didn’t set off any bazookas and basically held ground on monetary policy. In its – Summary of Opinions at the Monetary Policy Meeting on July 28 and 29, 2016 – (released August 8, 2016), we detect some tension among the Board members as to the effectiveness of monetary policy as a counter-stabilisation force (altering the economic cycle). The distinguishing feature about Japan is that monetary and fiscal policy are working in harmony in contradistinction to other nations (or currency blocs) where monetary easing is being accompanied by fiscal contraction. The latter ensures that growth will not occur, while the former provides a virtuous cycle. The recent retail sales data for Australia, released last week by the Australian Bureau of Statistics provides further evidence that monetary policy is not very effective in stimulating spending. The same data demonstrated categorically in 2009 how effective fiscal policy can be. It is time for the Australian government to shift policy positions and introduce another major fiscal stimulus and stop relying on the central bank to salvage what is becoming an ugly situation. The latter simply hasn’t got the policy tools available to fulfill the task it has been (implicitly) set by the Government’s irresponsible pursuit of fiscal surpluses.”

3 Ingelesez: “So the combination of aggressive fiscal stimulus supported by a very easy monetary stance has given Japan a labour market outcome that any nation would be envious off – notwithstanding all the claims about ‘lost decades’, ‘ageing population’, ‘excessive government debt’, ‘sclerotic society’.

The PIMCO (A report for Pimco by Tomoya Masano (August 6, 2016) – The BOJ Hit Its Limit: A Summer Relief for Banks – ) article concludes by saying that:

Perhaps it is time for monetary policy to move to a back seat and let fiscal policy take the wheel.”

4 Ingelesez: “Well it is hardly the case that the Japanese government has been shy in expanding the fiscal deficit at the national level. The reality is that the Japanese government knew full well that a solitary reliance on monetary policy would be insufficient to restore growth and reduce unemployment.

They operated their two large macroeconomic policy levers in harmony as one of the Board members from the Bank of Japan noted (…).”

5 Ingelesez: “This is quite unlike what has been happening in other places – for example, the Eurozone where the fiscal stance has been largely contractionary while the ECB searches for one bazooka or another to fire.”

6 Ingelesez: “A similar problem exists in Australia where the Treasury (under the control of a conservative government) has been stifling fiscal policy flexibility in pursuit of a fiscal surplus – albeit they have struggled to cut the deficit given the cycle has turned against them and taxation revenue has not met their expectations.

The on-going fiscal deficit is thus supporting growth but needs to be much larger.”

7 Ingelesez: “A famous article by Norwegian economist Axel Leijonhufvud – Keynes and the Effectiveness of Monetary Policy – which was published in Economic Inquiry, Volume 6, Issue 2, pages 97–111, March 1968, noted that the American Keynesian tradition in the post World War II period:

… has been associated with a decided preference for fiscal over monetary stabilization policies … In the development of this school of thought, certain arguments to the effect that monetary policy is generally ineffective have historically played a large role.

He then argued that Keynes, himself, did express “doubts about the efficacy of banking policy and … argued for public works programs” (that is, fiscal policy initiatives) but that his position was more complicated than the American Keynesians made out.

Leijonhufvud wrote that Keynes was aware that expenditure could become insensitive to interest rate changes and that monetary policy was not a suitable tool when an economy was caught in a deep recession and no one wanted to borrow.”

8 Ingelesez: “The current debate about monetary policy evokes a strong sense of déjà vu, given that these points were debated and understood during the 1930s.

The expression – pushing on a string – describes the situation where central banks may be able to inhibit credit creation by the commercial banks (by making the price it provides reserves prohibitive) but it cannot force the banks to lend.

The analogy tells us that the influence of monetary policy on total spending in the economy is likely to work in one direction (pulling the string) but not the other (pushing).”

9 Ingelesez: “On December 16, 1933, as the Great Depression was worsening and policy makers were relying on monetary policy solutions, similar to the emphasis in the current crisis, Keynes, who is often credited with the ‘pushing on a string’ analogy, wrote an – Open Letter to President Roosevelt – and said:

Some people seem to infer from this that output and income can be raised by increasing the quantity of money. But this is like trying to get fat by buying a larger belt. In the United States today your belt is plenty big enough for your belly. It is a most misleading thing to stress the quantity of money, which is only a limiting factor, rather than the volume of expenditure, which is the operative factor.

In that context, he said that the government “must be called in aid to create additional current incomes through the expenditure of borrowed or printed money”.”

10 Ingelesez: “In a similar vein, on March 18, 1935, the US House of Representatives Committee on Banking and Currency considered the introduction of the Banking Act of 1935, which was designed to “provide for the sound, effective, and uninterrupted operation of the banking system …” (Committee on Banking and Currency, 1935).

On that particular afternoon, the Federal Reserve Bank Chairman, Marriner Eccles was interrogated by Congressman Thomas Alan Goldsborough about what the central bank could do to address the parlous state of the US economy.

The US economy was mired in a deep depression, not unlike the situation that the euro-zone finds itself in today. The unemployment rate was around 21 per cent.

Their exchange was clear (p.377):

Governor Eccles: Under present circumstances, there is very little, if anything, that can be done.” (p.377)

Mr Goldsborough: You mean you cannot push on a string.

Governor Eccles: That is a very good way to put it, one cannot push on a string. We are in the depths of a depression and, as I have said several times before this committee, beyond creating an easy money situation through reduction of discount rates and through the creation of excess reserves, there is very little, if anything, that the reserve organization can do toward bringing about recovery …”

11 Ingelesez: “The GFC and its aftermath has demonstrated categorically the power of fiscal policy (spending and taxation). When private spending collapsed, the solution was simple and well-known.

The US government knew what to do: ease monetary conditions and introduce a large-scale fiscal stimulus. The Chinese government did the same, as did the Australian government and several others.

All the governments that followed the basic rules of macroeconomics that spending equals income, which drives employment, were able to offset, to varying degrees, the private sector meltdown.”

12 Ingelesez: “Australia’s fiscal stimulus package was large enough and was introduced early enough (in late 2008 and early 2009) to allow it to avoid a recession altogether.

The Australian Treasury – providing a briefing at a conference in Sydney on December 8, 2009 – The Return of Fiscal Policy.

They noted that the fiscal interventions, which combined cash transfers and investment:

… were designed to ensure that support was provided to the economy as quickly as possible …

The retail sales graph (above) shows what statisticians call the ‘intervention effect’ very clearly.

The Australian Treasury concluded that:

… the first cash transfers to households were distributed in early December 2008. Retail trade jumped by 4 per cent in that month, having shown almost no growth earlier in 2008.

So even though interest rates were declining, the stimulus to retail spending only came with the fiscal intervention.

The Treasury also note that the fiscal stimulus saved the construction sector, which normally is one of the first sectors to go into recession as aggregate spending collapses.

Their overall conclusion was that:

… the expansionary macroeconomic policy response was large enough and quick enough to convince the community — both consumers and businesses — that the slowdown would be relatively mild … Macroeconomic policy supported economic activity, which in turn convinced consumers and businesses that the slowdown would be relatively mild. This in turn led consumers and businesses to continue to spend, and led businesses to cut workers’ hours rather than laying them off, which in turn helped the economic slowdown to be relatively mild.

And that:

… absent the discretionary fiscal packages, real GDP would have contracted not only in the December quarter 2008 (which it did), but also in the March and June quarters of 2009, and therefore that the economy would have contracted significantly over the year to June 2009, rather than expanding by an estimated 0.6 per cent.

So it was fiscal policy that saved Australia from recession, not monetary policy.”

13 Ingelesez: “The Treasury concluded that even though interest rates had come down quickly and significantly (by record proportions in fact):

… this fall in real borrowing rates would have contributed less than 1 per cent to GDP growth over the year to the September quarter 2009, compared with the estimated contribution from the discretionary fiscal packages of about 2.4 per cent over the same period.

So fiscal policy was 2.4 times more effective than monetary policy at meeting the problem wrought by a collapse in private spending.

Subsequent evaluations by government bodies including the American Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and many other economists found that the fiscal interventions were highly successful albeit too conservative and withdrawn too early.

The fact that many of these same governments sooner or later were bullied by the conservative political lobbies into withdrawing or modifying the stimulus packages, which then undermined the emerging recoveries they had earlier created, doesn’t alter the point.”

14 Ingelesez: “These lessons appear not to have been learned – except perhaps in Japan – which has achieved substantial cuts in the unemployment rate because it has not relied exclusively on monetary policy.

Monetary and fiscal policy have operated harmoniously!”

15 Ingelesez: “The Australian government should take heed and ditch its neo-liberal obsession with fiscal cuts and, instead, take the RBA Governor’s advice and spend up big on productive infrastructure that will take Australia into the latter part of this century.”