Bill Mitchell-en Germany’s serial breaches of Eurozone rules1

Hona hemen aipaturiko punturik garrantzitsuenak:

(a) 2015eko iragarpena Alemaniaz2

(b) 2010eko egoeran3: Troika eta Alemania4

(c) Egonkortasun eta Hazkundeko Itun berriaz5

(d) Politika fiskala gehiago estutzeko neurri berriak: Six-Pack6, Two-Pack7 eta Fiscal Compact8

(e) Aipatutako aldaketa guztiak Alemaniak bultzatu eta gidatu zituen: esportazio netoen alde9

(f) Langabezia10

(g) Kontu korronteko defizitak11

(h) 2015eko txostenaren iragarpena eta Alemania12

Lehen grafikoa:13

Bigarren grafikoa14:

(i) Alemania: 2015eko txostena15

(j) 2014ko ‘gomendioak’16

Hirugarren grafikoa17:

(k) Esportazio netoen balantzea18

Taula:

“According to the data contained in – Foreign Trade – Ranking of Germany’s trading partners in foreign trade – issued by the German Federal Statistical Office (Statistisches Bundesamt) on April 20, 2015, the following Net Export balances were achieved in 2014:”

1. US 47,496,531 (in 000s Euros)

2. UK 41,837,960

3. France 34,440,831

4. Austria 19,755,255

5. UAE 10,658,512

6. Spain 9,984,037

7. Poland 7,992,050

8. Saudi Arabia 7,819,171

9. Korea 7,629,929

10. Sweden 7,445,632

11. Switzerland 6,931,741

12. Turkey 6,001,148

13. Italy 9,942,461

14. Australia 5,774,383

15. Mexico 5,405,176

16. Denmark 4,996,424

17. Canada 4,892,423

18. Hong Kong 4,391,533

19. South Africa 3,415,267

20. Greece 3,213,418

(l) Alemaniak besteei esan berak egiten ez duena19

Ondorioak:

Alemaniak segitzen du bere euroguneko kideak ehizatzen. Batasun monetario komunerako Alemariaren fokapen merkantilistikoak kanpo merkataritza superabit masiboak sortzen ditu, zeintzuk gero euroguneko kideei kapital esportazio moduan azaltzen zaizkien. Hauek inbertsiogileentzako irabazi baxuak sortzen dituzte eta batasun monetarioaren barruan are gehiago konplikatzen dute zor dinamika.

Alemaniako populazioak ez du irabazten, ezta Alemaniaren EBko kideak.

Egoera zoroa da.

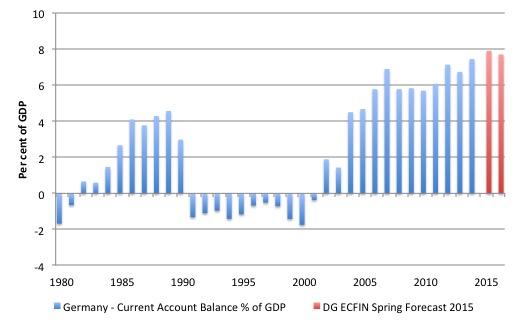

2 Ingelesez: In 2015… “… the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Economic an Financial Affairs (ECFIN) published the – Spring 2015 European Economic Forecast – which provide a picture of what they think will happen over the next two years across 180 variables. To the extent that the forecasts reflect past trends (given the inertia in economic time series outside major cyclical events), they provide a clear picture of what is wrong with the Eurozone. The salient feature of the Forecasts is that the European Commission expects Germany to increase its already astronomical Current Account surpluses to peak at 7.9 per cent of GDP in 2015 and falling only to 7.7 per cent in 2017. The Commission has in place a set of rules that require nations to restrict external surpluses to not exceed 6 per cent of GDP. Germany repeatedly fails to abide by those rules, yet lectures the rest of its Eurozone partners about their failures to meet the targets, crazy as they are. The unwillingness of the European Commission to enforce their own rules in relation to Germany is one of the telling failures of the whole Eurozone experiment.”

3 Ingelesez: “In 2010, the European Council was under increasing pressure to respond to the apparent failure of macroeconomic policy and governance arrangements in the monetary union.

The Council had brutalised Greece by entering a deal with the ECB and the IMF (the Troika) which in its early forms had proposed that a European Commissioner take over running economic policy in Greece, which a British academic lawyer, Costas Douzinas noted in his UK Guardian

article at the time (March 5, 2010) – What Now for Greece – Collapse or Resurrection? “… was more than a little insensitive for a country that has suffered a brutal Nazi occupation”.”

4 Ingelesez: “Facing increasing hostility, the Troika decided to create a ‘task force’ of inspectors who would rough ride over the democratic process to make sure that the Troika got their pound of flesh.

But the time the European Council met in Brussels in March 2010, the shape of the response that the political leaders would take was clear.

The – Statement by the Heads of State and Government of the Euro Area – issued on March 25, 2010, said that:

We reaffirm that all euro area members must conduct sound national policies in line with the agreed rules and should be aware of their shared responsibility for the economic and financial stability in the area … The current situation demonstrates the need to strengthen and complement the existing framework to ensure fiscal sustainability in the euro zone and enhance its capacity to act in times of crises.For the future, surveillance of economic and budgetary risks and the instruments for their prevention, including the Excessive Deficit Procedure, must be strengthened. Moreover, we need a robust framework for crisis resolution respecting the principle of member states’ own budgetary responsibility.

Up to that point, the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) combined with the Excessive Deficit Procedure were the major expressions of macroeconomic rules and governance in the Euro area.

The German agenda around these 2010 meetings was clearly to make the SGP conditions even more onerous so as to further constrain discretionary fiscal policy, which ensured that only nations with strong export positions would have any chance of sustained growth.”

5 Ingelesez: “In a Wall Street Journal Op Ed (April 20, 2010) – How to Save the Euro – conservative German academic Hans-Werner Sinn called for a new SGP:

… one that would be formulated to impose ironclad debt discipline. What is needed are modified debt rules, hefty sanctions, and most of all, a system of rules that automates the levying of penalties, leaving no room for political meddling.

Sinn engaged in an incredibly hypocritical attack on Greece profligacy – their unwillingness to pay for their import bill with real resources rather than debt – never noting, of-course, the role that German exports played nor German creditors, in the external deficits of its Eurozone neighbours.

He wanted the European Union to make “an example” of Greece and said that “Only by making an example can the EU hope that the new rules for indebtedness will be adhered to”. Tough talk.

The European Union’s response to this pressure was embodied in three new ‘governance’ measures – the Six-Pack, the Two-Pack and the Fiscal Compact.

All three initiatives sought to further restrict the fiscal flexibility of the national governments. All three took the monetary union further into the mire and further away from an effective solution to its woes.

The presumption was that if the fiscal rules were tighter and behaviour more closely monitored and controlled, the SGP would be enforceable and the so-called fiscal crisis would dissipate. The European leadership was clearly prepared to let higher unemployment and poverty become the adjustment mechanism rather than government spending.”

6 Ingelesez: “In late 2011, the Commission proposed a major revision of the SGP, which was approved by the Member States and the European Parliament in October 2011. The so-called ‘reinforced Stability and Growth Pact (SGP)’ became operational on 13 December 2011.

The – EU Economic governance “Six-Pack” enters into force (European Commission, 2011).

European Commission (2011) ‘EU Economic Governance “Six-Pack” Enters into Force’, MEMO/11/898, Brussels, 12 December.

The Official Memorandum – EU Economic governance “Six-Pack” enters into force – issued on December 12, 2011, said the so-called ‘Six-Pack’ comprised “five regulations and one directive.”

The innovation was the creation of a new “Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure”, which was described as a “new surveillance and enforcement mechanism”.

Essentially nations would move into the Excessive Deficit Procedure more quickly and there would be harsher sanctions for compliance failure.

Among other changes, the Six-Pack introduced a series of interventions under the so-called Excessive Imbalances Procedure (EIP), which aimed to reduce macroeconomic imbalances (particularly unit costs, external imbalances and so on) and force nations to submit “a clear roadmap and deadlines for implementing corrective action”.

The whole system became subject to a huge surveillance operation (EU monitoring) with rigorous enforcement (fines equal to 0.1 per cent of GDP) and central intervention in a nation’s budgetary process.”

7 Ingelesez: “The Two-Pack, which became enforceable on 30 May 2013, extended the surveillance mechanisms by requiring national governments to submit detailed fiscal plans to the Commission prior to their own enacting legislation. The Commission would not have the right to veto the plan, but could warn a national government of potential for breach. Further, any government receiving bailout money or in an EDP, would be subject to more detailed scrutiny by the Commission. In other words, more centralised bullying.”

8 Ingelesez: “But the Eurozone leaders were still not satisfied with these new restrictions. They decided to introduce an even more onerous set of fiscal rules under the guise of the Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union (TSCG), also known as the ‘Fiscal Compact’.”

9 Ingelesez: “These changes were driven by the Germans, who in 2009 enshrined a ‘balanced budget rule’ or ‘debt brake’ in their Basic Law (Constitution).

(…)

In other words, they wanted the government to run fiscal surpluses as a matter of course, imparting a constant fiscal drag on economic growth independent of the state of the economy.

In the context of German domestic policy, this means the only source of growth would be net exports. Further, the only way the government would be able to consistently produce fiscal surpluses would be to have continuous and large external surpluses, given the high saving propensity of German households.”

10 Ingelesez: “A nation that had endured an unemployment rate of say 9.9 per cent for the last three years is not considered to be imbalanced, given the warning threshold is 10 per cent.

The Commission chose this very high threshold due to a “focus on adjustment in labour markets and not on cyclical fluctuations”.

In other words, they do not consider the unemployment problem in terms of insufficient jobs being caused by deficient levels of spending but rather consider the only policy concern to be so-called “structural” issues. This in turn concentrates their attention on “market impediments”, the standard neo-liberal, supply side bias that has failed since it became the dominant approach in the early 1990s.

In the Commission”s annual “Alert Mechanism Report”, which is based on a review of the MIP scoreboard, any reference to unemployment is usually accompanied by some conclusion that wages are too high and need to be reduced in line with productivity growth. There is no recognition that the enduring recession has caused both productivity growth to slump and jobs to disappear due to a lack of spending.

The European policy makers are thus “content” with very high levels of unemployment yet they hide their intent in a language of deception.”

11 Ingelesez: “Another bias is evident in the way they deal with current account deficits and surpluses. They conclude that “sustained current account surpluses do not raise the same concerns about the sustainability of external debt and financing capacities, concerns that can affect the smooth functioning of the euro area” as do current account deficits.

The MIP thus accords “a greater degree of urgency” to “countries with large current account deficits and competitiveness losses”.

The upper warning threshold (for a surplus) is 6 per cent of GDP. If the balanced budget rule is satisfied by a nation sitting on the current account surplus threshold, then its private domestic sector will be saving overall 6 per cent of GDP. Where will those savings go?

Germany worked out early in its Eurozone membership that had to find a new way to maintain its external competitiveness once it could no longer manipulate the exchange rate.

The Hartz reforms reduced the capacity of workers to gain real wage increases which would allow them to share in the productivity growth of the economy. They also suppressed domestic spending. Profitable investment opportunities were limited in the German economy as a result and capital sought profits elsewhere.

The persistently large external surpluses (and 6 per cent is large) were the reason that so much debt was incurred in Spain and elsewhere.

(…)

The European Commission concluded that Germany had a macroeconomic imbalance as a result of its current account surplus being above the 6 per cent threshold.”

12 Ingelesez: “In the Spring Forecast, we read that:

Structural reforms implemented so far are starting to bear fruit in some Member States but overall remain insufficient to definitively overcome legacies of the crisis and significantly increase medium-term growth potentials.

There is no mention in the introduction that contains that assessment about Germany’s massive and expanding current account surplus.

Later on, we read that:

Germany’s surplus increased further due to muted corporate investment, which offset a slight improvement in household demand.

The Forecast says that:

… the current account surplus is nonetheless set to rise further in 2015 due to improvements to the terms of trade

The DG ECFIN Spring Forecast suggests that the current account surplus will rise to 7.9 per cent of GDP in 2015 and 7.7 per cent in 2016.”

13 Ingelesez: “The first graph shows the Current Account balance for Germany as a per cent of GDP from 1980 to 2014. The DG ECFIN Spring Forecast 2015 are shown in the red bars for the years 2015 and 2016.

The history shows how Germany transformed its economy in the early days of joining the common currency by embarking on a massive export surplus.

The very large external surpluses explain both why the government can run a fiscal surplus and domestic savings can remain high. (Ikus lehen grafikoa)

The DG ECFIN argues that the rising external surplus will be driven by the trade balance which is expected to rise further because of favourable euro exchange rate movements and rising prices for export goods (terms of trade).

They think that import growth may rise if investment picks up and domestic consumption strengthens.”

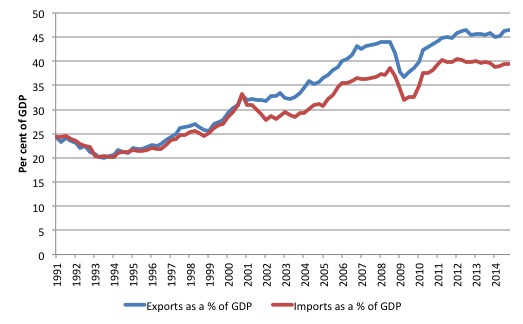

14 Ingelesez: “The following graph shows the trade components of the Current Account balance as a share of GDP. But it is clear that in the recent years, imports have fallen as a proportion of GDP. Germany is doing nothing to increase the share of imports.”(Ikus bigarren grafikoa)

15 Ingelesez: “In its – Country Report Germany 2015 – under the “In-Depth Review of the prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances” (released March 18, 2015), the European Commission noted that:

1. “The current account consistently shows a very high surplus, which is projected to increase to 8 % of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2015”.

2. They put this down to a “strong competitiveness …. in the export-oriented manufacturing sector, and high revenues from private sector investment abroad, which have not been offset by increased domestic demand, in particular due to weak investment. ”

3. “Consistently weak business investment and insufficient public investment remain a drag on growth”.”

16 Ingelesez: “They also concluded that Germany had made only “limited progress in addressing the 2014 country-specific recommendations”. Specifically:

-

Germany has not increased public investment as recommended and it is currently “insufficient to address the investment backlog in infrastructure, education and research.”

-

Germany has done nothing to reform the high taxation system.

-

Germany has not increased the minimum wage sufficiently.

-

Germany has not acted “to ensure the sustainability of the pension system.”

-

Other disincentives to work remain.

-

No “significant efforts” have been taken to implement the reforms recommended for the transport and service sectors.

Now, I should qualify this. Most of the reforms noted above are of a neo-liberal variety, which are designed to tilt the playing field further towards capital and undermine the scope and quality of public service provision. So to some extent it is better that Germany has been a laggard.

The point is that within the logic of the Eurozone and the draconian approach taken towards Greece, Germany appears to be a recalitrant. They don’t walk the talk.

Whatever way one wants to spin it, the external situation in Germany is well beyond the 6 per cent limit required by the MIP and the divergence is predicted to increase.

The question then is why isn’t Germany being hauled before the Commission and fined under the MIP?”

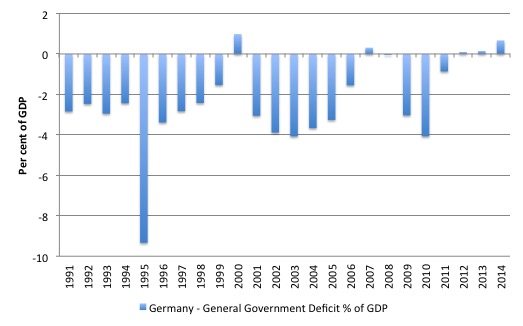

17I ngelesez: “The next graph shows the General Government fiscal balance (deficit is negative) as a per cent of GDP for Germany from 1991 to 2014 (using the Maastricht criteria).

Germany struggled in the early years of their membership of the Eurozone with deficits well in excess of the Maastricht fiscal rules (maximum of 3 per cent of GDP), which I wrote about that in these blogs – Eurozone battle lines being drawn again with Germany on the other side and

Germany contracts as the French suggest defiance – among others.

But while Germany lectures the rest of Europe about its fiscal superiority, the only way they can run these surpluses now, given it is suppressing domestic demand and reducing the well-being of its own people, is because it is exploiting the current account deficits of other nations, many of them its own Eurozone partners.” (Ikus hirugarren grafikoa).

18 Ingelesez: “The European Commission claimed in early 2014 that it would review the German external surpluses. “(Ikus Taula)

In terms of proportions around 50 per cent of the net exports surplus is due to trading within the Eurozone. But even so, the surpluses reflect the competitiveness of Germany’s manufacturing sector and the suppression of domestic demand.”

19 Ingelesez: “While Germany preaches to others about structural reforms, it fails to introduce necessary reforms which would not only increase the well-being of its own population but ease the crisis elsewhere in Europe.

It also means that the task facing nations like Greece is even more difficult – impossible in fact.

The Germans demand that Greece continues to grind its population into further poverty while their own policies mean that that the Greeks are chasing an ever elusive goal.

None of the goals – external surpluses, domestic devaluation, austerity – make sense. They reinforce each other and further the crisis.

The other problem is that the on-going German surpluses push up the value of the euro, which means all its talk of export-led growth for Greece and other beleagured nations becomes more difficult to achieve, given they do not have the level of external competitiveness that Germany exhibits.

Germany is clearly capable of addressing these issues. But it consistently fails to and remains in breach of the crazy European Commission rules.”