Nola sortu moneta berria, kasu ‘euskoa’, hutsetik?

Stephanie Kelton: How To Create A Currency From Scratch (Long Version)1

Professor Stephanie Kelton (UMKC and economic adviser to Bernie Sanders) running a little live currency creation experiment! She begins by levying a tax on the subjects of her nation Keltonia, in order to create a demand for her currency, Keltoni. This leads to her citizens demanding that she spend some Keltoni into existence, so that they have the Keltoni to pay the tax. She then does this, spending 500 Keltoni, and taxing 200, for a deficit of 300. Since Kelton has a deficit of 300 Keltoni (she has spend more than she has taken in) this must mean that the non-Kelton sector has a surplus of 300 Keltoni (it has taken in more than it has spent out).

Keltonia: Euskal Herria

Keltoni: euskoa

Zergapetzea EHn: EHko hiritarren gaineko zerga ezartzea , euskorako eskari bat sortzearren.

Eusko batzuk existentzian jartzeko, hiritarrek zergak ordaintzearren, euskoak edukitzearren, gobernuak gastatu egiten du, demagun 500 eusko…

Zergak: 200 eusko

Defizita: 300 eusko

Gobernuak 300 euskoko defizita daukanez (gehiago gastatu du berak bildu duena baino), horrek esan nahi du sektore pribatuak 300 euskoko superabita daukala (gehiago lortu du gastatu duena baino).

Then her citizens decide to import some goods from a foreign country. The foreigners are willing to accept Keltonis because they want to buy what the people of Keltonia export. They spend 100 Keltoni, which results in 100 Keltoni leaving Keltonia, ending up in the foreign sector.

Hiritarrek erabakitzen dute ondasun batzuk inportatzea. Atzerritar hiritarrek euskoak onartzen dituzte, zeren erosi nahi baitute EHk esportatzen duena.

Hiritarrek 100 eusko gastatzen dituzte, 100 eusko Euskal Herritik joaten dira, atzerritar sektorean bukatuz.

This illustrates the principle of sectoral balances. The people of Keltonia now have 200 Keltoni, the foreign sector has 100, and Professor Kelton has -300. The surpluses/deficits of each of these sectors must add to zero: 200 + 100 + -300 = 0. This is an accounting identity.

Sektore-balantzeen printzipioa

Euskal Herriko jendeak orain 200 eusko dauka. Atzerritar sektoreak 100 dauzka eta gobernuak -300.

Sektore horien superabitak/defizitak batera zero izan behar da: 200 +100 -300 = 0. Hori kontabilitate identitatea da.

The important takeaway here is that in order for the people of Keltonia (the domestic private sector) to be in surplus, then either Professor Kelton (the government) or the foreign sector or both must be in deficit to supply these funds. If the foreign sector is in surplus (confusingly called a “trade deficit”) this means that financial assets are net leaving the domestic private sector to go off to foreign lands, so the government must run an even larger government deficit to compensate to supply those funds.

Euskal Herriko jendea (barneko sektore pribatua) superabitean egoteko, orduan gobernua ala atzerritar sektorea edo biak defizitean egon behar dira, fondo horiek hornitzeko.

Baldin eta sektore atzerritarra superabitean badago (modu nahasi batez ‘merkataritza defizita’ deitzen dena), horrek esan nahi du aktibo finantzario netoek barneko sektore pribatutik alde egiten dutela atzerritar herrialdetara joateko, beraz, gobernuak are gobernu defizit handiagoa izan behar du fondo horiek hornitzeko konpentsatzearren.

Gehigarriak:

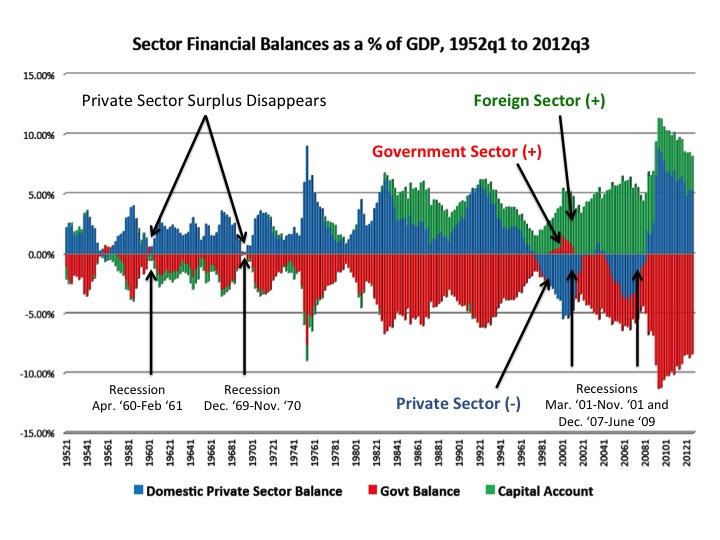

(i) Azken Atzerapen Globalaz: sektore pribatua defizitean, aktiboak galduz, eta gero eta zordunago bilakatuz. Zorrak azkenean ezin direlako ordaindu, krak edo hondamendia gertatu zen

Professor Kelton then goes on to show the graph of United States sectoral balances. Modern Money Theorists were predicting the Great Recession as early as the 1990s, because the private sector had gone into deficit, meaning the private sector was losing assets and becoming more and more indebted. That kind of thing is unsustainable for very long, and eventually results in a crash as debts can no longer be paid.

(ii) Bonoen salmentak, aurreztaileei interesak ordaintzearren. Dolarrak metatzen dituzten atzerritar inbertitzaileek zein atzerritar herrialdeek ez dute zamatzen barneko sektore pribatua. Gobernuak ez du behar zergak altxatzea bono-edukitzaileei atzera ordaintzearren.

And finally, Kelton demonstrate how bond sales work. First, a bond sale by the government is NOT “borrowing money,” but rather is a service to pay interest to savers. (The government doesn’t need its own currency back in order to spend, and you can’t even buy a bond until the government has first spent some currency into existence so that you have the bond). Investors and foreign nations who accumulate our currency (because they run trade surpluses against us) choose to buy our bonds because the bonds pay interest, while the cash they hold doesn’t. This in no way burdens the domestic private sector though: the government does not need to raise taxes in order to spend or pay back bondholders.

Euskoa ateratzeko prozedura

Hasierarako, ikus

Warren Mosler Italiara, berriz

Segida:

DTM lau eskematan (euroa eta lira)

https://www.unibertsitatea.net/otarrea/gizarte-zientziak/ekonomia/dtm-lau-eskematan-euroa-eta-lira

Ongi etorri euskoa!

https://www.unibertsitatea.net/otarrea/gizarte-zientziak/ekonomia/ongi-etorri-euskoa

joseba says:

How To Start A Currency From Scratch (Short Version):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?list=PLZJAgo9FgHWZzhpkjtMxIwZns26A0OdFz&v=8W1zA_CgYMk

Professor Stephanie Kelton (UMKC and economic adviser to Bernie Sanders) running a little live currency creation experiment! She begins by levying a tax on the subjects of her nation Keltonia, in order to create a demand for her currency, Keltoni. This leads to her citizens demanding that she spend some Keltoni into existence, so that they have the Keltoni to pay the tax. She then does this, spending 500 Keltoni, and taxing 200, for a deficit of 300. Since Kelton has a deficit of 300 Keltoni (she has spend more than she has taken in) this must mean that the non-Kelton sector has a surplus of 300 Keltoni (it has taken in more than it has spent out).

Then her citizens decide to import some goods from a foreign country. The foreigners are willing to accept Keltonis because they want to buy what the people of Keltonia export. They spend 100 Keltoni, which results in 100 Keltoni leaving Keltonia, ending up in the foreign sector.

This illustrates the principle of sectoral balances. The people of Keltonia now have 200 Keltoni, the foreign sector has 100, and Professor Kelton has -300. The surpluses/deficits of each of these sectors must add to zero: 200 + 100 + -300 = 0. This is an accounting identity.

The important takeaway here is that in order for the people of Keltonia (the domestic private sector) to be in surplus, then either Professor Kelton (the government) or the foreign sector or both must be in deficit to supply these funds. If the foreign sector is in surplus (confusingly called a “trade deficit”) this means that financial assets are net leaving the domestic private sector to go off to foreign lands, so the government must run an even larger government deficit to compensate to supply those funds.

And finally, Kelton demonstrate how bond sales work. First, a bond sale by the government is NOT “borrowing money,” but rather is a service to pay interest to savers. (The government doesn’t need its own currency back in order to spend, and you can’t even buy a bond until the government has first spent some currency into existence so that you have the bond). Investors and foreign nations who accumulate our currency (because they run trade surpluses against us) choose to buy our bonds because the bonds pay interest, while the cash they hold doesn’t. This in no way burdens the domestic private sector though: the government does not need to raise taxes in order to spend or pay back bondholders.

See the whole video here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ba8Xd…