(i) MOSLER: zenbait twitter

CBs wrongly assume forward prices, a function of policy rates, are expected prices. Instead, they are current prices for future delivery.

That is, the current term structure of prices presented to the economy, including the rate of change, is a function of CB policy rates.

The rate of change of the term structure of prices in the economy, a function of CB rate policy, is the textbook definition of inflation.

That is, the rate of inflation (as defined) presented to the economy at any given point in time is a direct function of CB policy rates.

2016 abu. 28

(ii) FED

Stephanie Kelton @StephanieKelton

Yellen said we may need to consider more effective automatic stabilizers. @pdacosta suggests Minsky’s ELR

2016 abu. 28

The Stimulus Our Economy Needs2

“… wouldn’t it be better to directly create government jobs in areas where the private sector appears to be falling short? Employer-of-last-resort-type policies, as proposed by the economist Hyman Minsky, where the government generates employment in socially useful sectors that are underserved by the private sector alone — including infrastructure, education, health care, child and elderly care, and the arts — could be optimal. (…)”

(iii) Job guarante, lan bermea

Pavlina R Tcherneva @ptcherneva

MUST WATCH, if you ever wondered what a #JobGuarantee in the US could look like. https://www.facebook.com/UrbanFarmingGuys/videos/1223938064304551/?hc_ref=NEWSFEED …

2016 abu. 29

Bideoa: https://www.facebook.com/UrbanFarmingGuys/videos/1223938064304551/?hc_ref=NEWSFEED

(IV) BREXIT

Brexit is actually boosting the UK economy

“Two months ago, the world’s wise men were warning that if UK voters decided to “Brexit” from the European Union, they’d rain down economic crisis. Guess what? Today, Britain is fine — and has even seen a boost from its “Leave” vote.

The International Monetary Fund, central bank chiefs, academic economists — you know, the people who study the economy for a living — said Brexit would be a disaster.

Then-Prime Minister David Cameron warned that Britons who voted to leave would risk their Social Security-style pensions. President Obama said Britons would have to “go to the back of the queue” to ink trade deals with the United States.

(…)

Yes, Britain still has problems. Like the United States, it still depends on cheap credit to get people to buy houses and spend money. This — not Brexit — will cause another recession someday.

And workers’ retirement income is at risk — not because of Brexit, as Cameron said, but because private companies and the government have avoided making “required” contributions to pension funds for decades, leaving a $1 trillion-plus gap.

Britain needs better infrastructure. Its commuter trains are a mess — and more expensive — compared to Europe’s.

But these problems have nothing to do with Brexit.”

(Badakigu, monetari dagokionez, subiranoa den estatu bat, hots, bere moneta propioa jaulkitzen duena (kasu, gaur egungo Britainia Handia), gai izan daitekeela goian aipaturiko arazo horiek guztiak gainditzeko. Arazo horiek borondate eta nahi politikori dagozkie, ez inongo ezintasun objektibori, lehen, Europar Batasuneko arauekin gertatu zen bezala. Orain, Britainia Handia badauzka erreminta ekonomiko eta monetarioak bere arazoei aurre egiteko. Eginkizun horretan Alderdi Laboristak badauka zer esanik eta zer eginik, baldin eta soilik baldin, haren liderrek gaur egungo ekonomiaren funtzionamendua ulertuko badute…)

(V) EUROA

The One-Size Euro Mightn’t Be So Tight After All3

“It’s a given that the euro can’t have the right exchange rate for all of its 19 diverse members, all of the time. Yet at the helm of the European Central Bank, Mario Draghi may be making it a closer fit for more countries, more of the time.

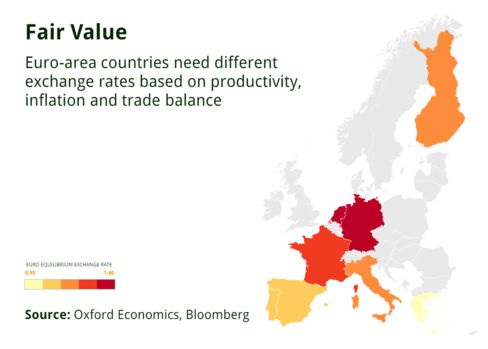

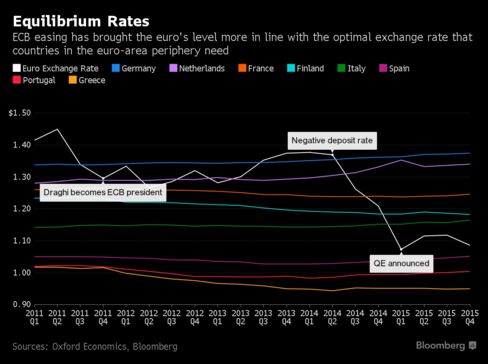

Angel Talavera, an economist at Oxford Economics in London, has calculated for Bloomberg Benchmark what would have been the “equilibrium” exchange rate for 8 euro-area economies between 2011 and 2015 − the rate that would be best suited to an economy’s domestic and external profiles.

As the map shows, Germany’s economic strength and positive balance of payments would warrant the euro trading at around $1.40, while Greece’s woes would require it to be below parity with the dollar. At the beginning of Draghi’s term, the euro was too strong for pretty much everyone, and has typically aligned itself more to the needs of “core” economies, Germany included. That hasn’t been helpful.

(ADI: Eurexit dela-eta)

“What would normally happen with a country that has its own currency is that the currency will appreciate or depreciate over time to help correct those imbalances,” Talavera said. “In the case of the Eurozone obviously you can’t have both things happening, so those imbalances are not correcting, but rather amplifying most of the time.”

His calculations bear this out. At the height of the sovereign-debt crisis in 2011 the spread between the optimal rate for Germany and Greece was $0.32. By the end of last year the gap had widened to $0.42.

But things are changing. The ECB’s more recent policies have weakened the exchange rate more toward what would be appropriate for countries like Italy or Spain. Since the announcement of negative rates in June 2014, the euro slid by almost 20 percent against the dollar. While that’s still too strong for Greece, it’s closer to the average.

The average spread between countries’ optimal rate and the actual euro level has fallen from $0.25 at the beginning of 2011 to $0.14 at the end of 2015.

Given the structure of the euro, though, there may be only so much that the current set of policies can do. According to Talavera’s Oxford Economics study, the ECB’s monetary policy has always been plagued by a paradox: while it has has been “generally right for the common currency area as a whole, it has proven to be wrong for most of its individual members most of the time.”

(Alegia, ortodoxoak ere konturatzen dira euroa amesgaizto bat dela, paradoxa batean bizi dela.)

(VI) LANGABEZIA

Langabezia froga da defizita oso txikia dela (W. Mosler)

Sorry, baina,

Repeat with me: Langabezia froga da defizita oso txikia dela

Esan berriz, nirekin: Langabezia froga da defizita oso txikia dela

Once more: Langabezia froga da defizita oso txikia dela

Beste behin: Langabezia froga da defizita oso txikia dela

Nahiko? Aski?