Bill Mitchell-en We need to read Karl Marx1.

(Orain dela bost urte idatzia.)

(a) Eman Marx-i aukera bat Mundu ekonomia salbatzeko2

(b) ‘Merkatu librea’: lan-indarra, zer dela eta agertzen da langabezia, zergatik bankuei diru-laguntza itzelak luzatzea eta deus ez enplegu publikoari3

(c) Ba ote dauka Marx-ek ezer egitekorik aipatutako guzti horrekin? George Magnus-en erantzuna4

Ikus dezagun, hortaz, G. Magnus-ek dioena:

(d) Mozkinak eta miseria: txapon bereko bi aldeak5

(e) Errenta desberdintasuna eta kreditu erreza: krisiaren jatorria6

The US income and wealth distributions….

(f) ‘Gain-produkzioaren eta azpi-kontsumoaren paradoxa’7

(g) Keynes, post-keynestarrak eta Marx-en Plusbalioaren Teoriak8

(h) Marx eta oraingo krisia, Magnus-en arabera9:

“policy makers have to place jobs at the top of the economic agenda”

Ondorioak:

(1) Interesgarria benetan finantza merkatuentzako aholkulari batek Marx plazara ekartzea10

(2) Kapitalak ez du inoiz maite enplegu osoa. Marx-ek bazekien hori. Klase-borrokak zutik dirau11

2 Ingelesez: “I know it is fashionable these days, particularly on the left to claim that class is dead – that its not about class any more – that left-right is dead – etc. But there was an interesting Bloomberg article (August 29, 2011) – Give Karl Marx a Chance to Save the World Economy – by one George Magnus, who is listed as a senior economic adviser at UBS Investment Bank. Confused? Why would a banker invoke the thoughts of the long-dead and usually vilified (by bankers) philosopher? For me it is always a normal part of thinking to go back to Marx because his dissection of capitalism – the sources of profits and the importance of seeing beyond the superficial exchange relations and thus understanding class relations embedded in production – has not, in my view, been bettered. And now a banker is suggesting that need to read Karl Marx.

Even so-called progressives these days, think it is fashionable to claim that class is dead – that its not about class any more – that left-right is obsolete – etc.”

3 Ingelesez: “They have a vested interest in developing the “free market” myth where we are all, essentially, free traders and own-producers at heart who agree (aided by market forces) to specialise into labour suppliers or capital providers. The myth continues that we are all free traders – everything is voluntary and all exchanges are mediated by market prices which deliver equalised use values to each exchanger to be enjoyed upon completion of the same.

(…)

The free market – everything can be understood at the exchange level – view falls in a hole when we focus on the labour market. After all, workers do not sell labour – they rather sell labour power (the capacity to work). That immediately invokes a managerial imperative. Why? Answer: because the use-value of the labour power is enjoyed (extracted) within the actual exchange (that is, while the workers are still at work). The use-value – the source of profit – is uncertain and a control function is indicated.

Bosses have to control the realisation of that use value as production in an environment where the majority of workers would rather not be there. That is a very different dynamic environment to one where we go into a shop and buy a trinket to be enjoyed later.

Essentially left and right, for me, is about class dynamics and I am using class in the Marxian sense here. I know there are complex layers over the basic capital-worker distinction and certainly these layers are exploited by the power elites to obscure them further (for example, gender, sexuality, race etc) but when push-comes-to-shove the struggle over the distribution of income arising from production is still highly significant.

We cannot really understand the crisis unless we understand the underlying class dynamics. Sure enough I usually say that the crisis is the result of poor government policy and a failure to employ the fiscal tools at the disposal of governments in an appropriate way. But the question that follows is WHY?

Why are our governments coming under pressure to tighten fiscal policy when it is clear that more spending is desperately required and it doesn’t look like it will come from the non-government sector?

Getting real – how is it that the political debate is being swamped by those who want large spending cuts at a time when unemployment and underemployment in the largest economy is moving close to 20 per cent?

How is it that we ignore the fact that every day, millions of workers are slowly or less slowly exhausting all the wealth that they had built up over their working lives just to live a basic life because their incomes have dried up through lack of work?

How is it that people who say that unemployment benefits should be cut now when for millions they are the only lifeline can even be taken seriously?

How is it that when the major investment banks of Wall Street (and elsewhere in other nations) – who had acted with as much regard for the law and civil society as the bootleggers and dope dealers of the prohibition period – looked like going broke as their bets exploded in their faces – could the government, within hours, announce massive bailouts – yet something as basic as creating public jobs at a minimum wage is deemed unaffordable?

How is it that thousands of criminals are still turning up for work each day in the financial sector and extracting massive bonuses for performing totally unproductive work when thousands of poor (black) individuals are being imprisoned every day for minor crimes against property and usually against their own kind?”

4 Ingelesez: “Anyway, what has Marx got to do with all of this?

George Magnus says that:

Policy makers struggling to understand the barrage of financial panics, protests and other ills afflicting the world would do well to study the works of a long-dead economist: Karl Marx. The sooner they recognize we’re facing a once-in-a-lifetime crisis of capitalism, the better equipped they will be to manage a way out of it.

This is being said by an advisor to an investment bank and is being published by Bloomberg.

The basis of Magnus’ call for us all to read Marx lies in his view that, while the “wily philosopher’s analysis of capitalism had a lot of flaws … today’s global economy bears some uncanny resemblances to the conditions he foresaw”.

I have been involved in my share of arcane debates about what Marx said and whether we can reinterpret his predictions (falling rate of profit etc) to make them square with the facts. Whatever utility we might get from those rather in-crowd debates, the bottom line is that the basic insights of Marx are still of relevance.

And in noting that we should start with reinstating attention to class.”

5 Ingelesez: “George Magnus says:

Consider, for example, Marx’s prediction of how the inherent conflict between capital and labor would manifest itself. As he wrote in “Das Kapital,” companies’ pursuit of profits and productivity would naturally lead them to need fewer and fewer workers, creating an “industrial reserve army” of the poor and unemployed: “Accumulation of wealth at one pole is, therefore, at the same time accumulation of misery.”

George Magnus then relates that insight to the current situation in the US “particularly” where “U.S. Companies’ efforts to cut costs and avoid hiring have boosted U.S. corporate profits as a share of total economic output to the highest level in more than six decades, while the unemployment rate stands at 9.1 percent and real wages are stagnant”.

I have written before about who has benefitted from the nascent growth in the US since the crisis began. Please read this blog – The top-end-of-town have captured the growth – which categorically shows that the employed workers have not enjoyed real wages growth while profits have soared and the growing ranks of the unemployed and underemployed have not enjoyed anything.

The neo-liberal period – crisis included – has been an attack on the conditions of workers and the suppression of the lower ends of the income distribution. In this blog – The origins of the economic crisis – I outline how deregulation has dramatically altered the distribution of national income over the last 30 years in the advanced nations with governments being the facilitators.”

6 Ingelesez: “George Magnus says that in addition to rising profits and entrenched unemployment:

U.S. income inequality, meanwhile, is by some measures close to its highest level since the 1920s. Before 2008, the income disparity was obscured by factors such as easy credit, which allowed poor households to enjoy a more affluent lifestyle. Now the problem is coming home to roost.

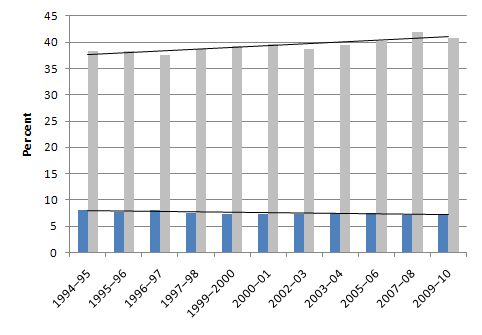

(…) The next graph shows the shares in total household income of the bottom (blue columns) and top (grey columns) quintiles of the income distribution. The black lines depict the linear regression trend of each of the series and the direction is obvious.

This data is consistent with the dramatic shifts in factor shares in national income. The data above is focused on the household unit. Factor shares is based on “class” in that it considers wage and profit income. The two distributional perspectives are tied together and offer different views of the same underlying trends (with some complexities).

One of the characteristic features of the last thirty or so years has been the dramatic rise in the profit share (and the commensurate fall in the wage share).

The assault on regulation and the attack on workers’ rights brought about a growing gap between labor productivity and real wage growth. The result has been a dramatic redistribution of national income toward capital in most countries. For example, in the G7 countries between 1982 and 2005 there was a 6 percent drop in the share of national income paid as wages (as opposed to interest or dividends). This was a global trend.

In the past, real wages grew in line with productivity, ensuring that firms could realize their expected profits via sales. With real wages lagging well behind productivity growth, a new way had to be found to keep workers consuming. The trick was found in the rise of “financial engineering,” which pushed ever increasing debt onto the household sector.

Capitalists found that they could sustain sales and receive an additional bonus in the form of interest payments—while also suppressing real wage growth.

Households, enticed by lower interest rates and the relentless marketing strategies of the financial sector, embarked on a credit binge.

The increasing share of real output (income) pocketed by capital became the gambling chips for a rapidly expanding and deregulated financial sector.

Governments claimed this would create wealth for all. And for a while, nominal wealth did grow—though its distribution did not become fairer. However, greed got the better of the bankers, as they pushed increasingly riskier debt onto people who were clearly susceptible to default. This was the origin of the subprime housing crisis of 2007–08.

This is what George Magnus is referring to when he talks about how “easy credit, which allowed poor households to enjoy a more affluent lifestyle” obscured the underlying inequality dynamics.”

7 Ingelesez: “George Magnus further invokes Marx when he talks about the “Over-Production Paradox”:

Marx also pointed out the paradox of over-production and under-consumption: The more people are relegated to poverty, the less they will be able to consume all the goods and services companies produce. When one company cuts costs to boost earnings, it’s smart, but when they all do, they undermine the income formation and effective demand on which they rely for revenues and profits.

As Marx put it in Kapital: “The ultimate reason for all real crises always remains the poverty and restricted consumption of the masses.”

This has been a topic that I have spent a lot of time thinking and writing about. We cover it in our 2008 book – Full Employment abandoned.”

8 Ingelesez: “Keynes used the inability of the Neoclassical economists to explain the reality of the 1930s to introduce the concept of involuntary unemployment. Understanding the meaning of involuntary unemployment requires a prior understanding of how the concept of effective demand was introduced into the analysis. The aim was to negate the Classical view that the real outcomes of the economy were determined by the full employment equilibrium achieved in the labour market. In other words, aggregate demand – or more correctly – effective demand matters.

Post Keynesians typically begin with Keynes’ General Theory (1936) in explicating the principle of effective demand. However, the essential elements underpinning the critique of Say and the modern understanding of involuntary unemployment in a monetary capitalist economy can be found in Marx, particularly in Theories of Surplus Value (1863).

Particularly in Chapter 17 there are various discussions about the Classical (Ricardian) denial of the possibility of generalised overproduction and how that erroneous view is based on the idea that products exchange against products. This is at the heart of Classical neutrality which ultimately is the modern version of the claim that fiscal and monetary policy cannot favourably alter real conditions in the economy.

In Theories of Surplus Value Vol 2, Chapter 17 (para 705) we read:

The conception (which really belongs to [James] Mill), adopted by Ricardo from the tedious Say (and to which we shall return when we discuss that miserable individual), that overproduction is not possible or at least that no general glut of the market is possible, is based on the proposition that products are exchanged against products, or as Mill put it, on the “metaphysical equilibrium of sellers and buyers”, and this led to [the conclusion] that demand is determined only by production, or also that demand and supply are identical. The same proposition exists also in the form, which Ricardo liked particularly, that any amount of capital can be employed productively in any country.

Marx really laid into Say. This paragraph also highlights why the use of “barter economy” examples is deeply flawed. A monetary economy has dynamics that are not captured in a barter world where products exchange against products directly.

If we mapped the current conservative (neo-liberal) position (and most of mainstream economics) back into the classical propositions that Marx was attacking we would find the correspondence to be close to 100 per cent in terms of concepts and implications.

They were wrong then and by logical extension they are wrong now.

The existence of a circuit breaker in the form of idle money stocks (recognising that money is more than a means of exchange but also an independent form of commodity) led Marx to conclude that there was the possibility of stagnation (defined as a conflict between purchase and sale) – (see Theories of Surplus Value Vol 2, Chapter 17, paras 710-711).

Interestingly, in TSV (Vol II, Ch XVII, para 712) Marx also anticipated the modern distinction between nominal and effective demand which lies in the understanding of the real contribution of Keynes. Marx noted that in denying the possibility of a general glut, Ricardo appeals to unlimited needs of consumers for commodities and any particular saturation would be quickly overcome by increased demands for other commodities.

He then (TSV, Vol II, Ch XVII, para 712) rhetorically asked for an explanation of the connection between ‘over-production’ and ‘absolute needs’ and indicated that capitalist production and quotes Ricardo’s denial of the “possibility of a general glut in the market”:

Too much of a particular commodity may he produced, of which there may he such a glut in the market, as not to repay the capital expended on it; but this cannot be the case with respect to all commodities; the demand for corn is limited by the mouths which are to eat it, for shoes and coats by the persons who are to wear them; but though a community, or a part of a community, may have as much corn, and as many hats and shoes, as it is able or may wish to consume, the same cannot be said of every commodity produced by nature or by art. Some would consume more wine, if they had the ability to procure it. Others having enough of wine, would wish to increase the quantity or improve the quality of their furniture. Others might wish to ornament their grounds, or to enlarge their houses. The wish to do all or some of these is implanted in every man’s breast; nothing is required but the means, and nothing can afford the means, but an increase of production …

Marx retorted:

Could there be a more childish argument? It runs like this: more of a particular commodity may be produced than can be consumed of it; but this cannot apply to all commodities at the same time. Because the needs, which the commodities satisfy, have no limits and all these needs are not satisfied at the same time. On the contrary. The fulfilment of one need makes another, so to speak, latent. Thus nothing is required, but the means to satisfy these wants, and these means can only be provided through an increase in production. Hence no general overproduction is possible.

What is the purpose of all this? In periods of over-production, a large part of the nation (especially the working class) is less well provided than ever with corn, shoes etc., not to speak of wine and furniture. If over-production could only occur when all the members of a nation had satisfied even their most urgent needs, there could never, in the history of bourgeois society up to now, have been a state of general over-production or even of partial over-production. When, for instance, the market is glutted by shoes or calicoes or wines or colonial products, does this perhaps mean that four-sixths of the nation have more than satisfied their needs in shoes, calicoes etc.? What after all has over-production to do with absolute needs? It is only concerned with demand that is backed by ability to pay. It is not a question of absolute over-production—over-production as such in relation to the absolute need or the desire to possess commodities. In this sense there is neither partial nor general over-production; and the one is not opposed to the other.

Note the reference to the capitalist market being “only concerned with demand that is backed by ability to pay. It is not a question of absolute over-production – over-production as such in relation to the absolute need or the desire to possess commodities.”

I urge you to read the whole section in Theories of Surplus Value because its wisdom lies at the heart of the modern problem of high unemployment and stagnant growth. Keynes didn’t offer much more than you can find in this work by Marx.”

9 Ingelesez: “George Magnus says that the message of Marx in the current crisis is that:

… policy makers have to place jobs at the top of the economic agenda, and consider other unorthodox measures. The crisis isn’t temporary, and it certainly won’t be cured by the ideological passion for government austerity.

He lists “five major planks” for revival:

1. “we have to sustain aggregate demand and income growth” and governments “must make employment creation the litmus test of policy”.

2. “lighten the household debt burden”. He thinks governments should assist low income households to “restructure mortgage debt, or swap some debt forgiveness for future payments to lenders out of any home price appreciation”. In this 2009 blog – When a country is wrecked by neo-liberalism – I outlined a desirable policy initiative to help home-owners who were facing eviction from their homes because they could no longer service their debts. It is similar to that being advocated now by George Magnus.

3. help banks “to get new credit flowing to small companies, especially” by relaxing capital adequacy rules and direct public “spending on or indirect financing of national investment or infrastructure programs”. The exact nature of the intervention is disputable but the intent is not. The solution must see aggregate demand being stimulated and with flat non-government spending, the responsibility for pushing the spending out lies with the government.

4. “to ease the sovereign debt burden in the euro zone, European creditors have to extend the lower interest rates and longer payment terms recently proposed for Greece”. While this would provide temporary relief it doesn’t get to the heart of the matter which is the flawed (and dysfunctional) design of the overall monetary system. Such “relief” would not solve the inherent problem.

5. “to build defenses against the risk of falling into deflation and stagnation, central banks should look beyond bond- buying programs, and instead target a growth rate of nominal economic output”. I do not support the central bank being a major player in counter-stabilisation policy. I will write about this in more detail another time.”

(Orain dela bost urte idatzia. Badakigu Mitchell-ek politika fiskala hobesten duela, ez inongo politika monetariorik.)

10 Ingelesez: “I found it interesting that a person who advises the financial markets would suggest that Karl Marx retained relevance. It is clear that capitalism has reached a crisis point after 3 decades of deregulation, privatisation, welfare cuts etc were argued would optimise its performance. It was clear that all this neo-liberal legislation did was to push more power to capital, redistribute real income away from the workers, and reduce the political capacity of governments to use fiscal policy and regulation to mediate the class struggle and sustain full employment.”

11 Ingelesez: “Capital has never like full employment. Marx knew that. The last thirty years or so has seen the gains made by workers and their unions over a century of struggle eroded away by the relentless attack on their rights and conditions.

The class struggle is alive and dominant this crisis.”

joseba says:

Frederick Engels on Karl Marx:

Karl Marx: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1877/06/karl-marx.htm