@tobararbulu # mmt@tobararbulu

An ABM Primer, Part One: Missed Opportunities

ooo

An ABM Primer, Part One: Missed Opportunities

The New START Treaty expires on Feb. 6. When it goes, there will be nothing to hold back a new nuclear arms race. To understand how this happened, we must go back to the beginning–to the ABM treaty.

Feb 01, 2026

A Sprint ABM being launched

(Note: This article contains material from my book, Scorpion King: America’s Suicidal Embrace of Nuclear Weapons from FDR to Trump, published in 2020 by Clarity Press. This is the first of a three-part series on the ABM Treaty, which served as the foundation for arms control in the nuclear era and without which there can be no meaningful progress in reviving arms control post New START.)

Early in the morning of October 14, 1964, in the desert test facility of Lop Nur, a team of technicians working under the supervision of a Yale-educated Chinese physicist named Chen Nengkuan assembled a nuclear device made from enriched uranium 235. After hoisting the device to the top of the test tower that had been photographed by the United States the previous spring, the Chinese detonated, at precisely 3:00 pm, a 20-kiloton nuclear device. The Chinese were quick to announce their achievement, but the United States, through its worldwide network of seismic stations, was also able to detect, isolate, and characterize the Chinese event.43 President Johnson decried the Chinese test as a “tragedy for the Chinese people,” but privately noted that China was a long way from having a deliverable weapon and that the specter of a nuclear-armed China was a problem that would be faced by a future president.

On November 3, 1964, the American people voted for their thirty-sixth president in one of the largest landslides in American presidential election history, larger than Franklin Roosevelt’s 1936 victory. Having assumed office in the aftermath of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination, Johnson had been concerned that he lacked a mandate to govern in his own right. He no longer needed to be concerned about that. Lyndon Johnson chose Hubert Humphrey, the champion of arms control and disarmament, as his vice president. President Johnson was congratulated by Soviet Prime Minister Kosygin and President Mikoyan, who just a month prior had removed Nikita Khrushchev from power in what amounted to an office coup. Moscow Radio, expressing a relief that was felt not only in the Soviet Union but also in Europe and the world as a whole that Johnson, and not his vehemently anti-communist Republican opponent, Barry Goldwater, had won, broadcast that the American people had chosen the “more moderate and sober policy” toward East-West relations. On the cusp of a time of historical change, President Johnson’s implementation of this “moderate and sober” mandate would dictate the course of the Cold War for decades to come.

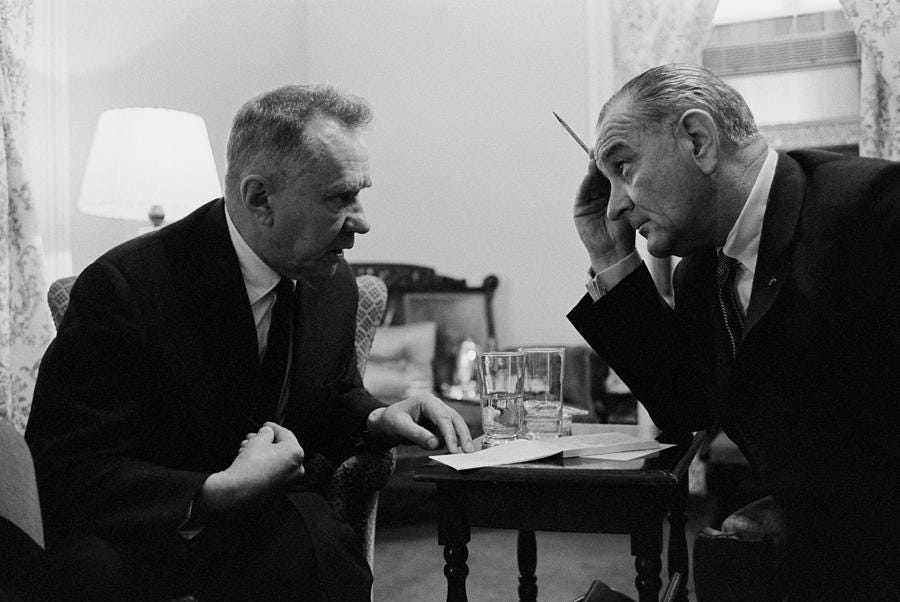

Lyndon Johnson (left) and Robert McNamara (right)

Now Johnson was the “future President.” The Chinese nuclear threat, or perceptions thereof, would now play a major role in propelling the United States down one of the more controversial arms acquisition paths of the nuclear age, one which continues to this day: ballistic missile defense. The Soviet missile threat was seen as being too massive to be viably countered by any system of surface-based missile interceptors. But the Chinese missile threat, comprised of a much smaller number of missiles, was a different story.

The Sino-Soviet schism, which came to a head in the late 1950s, allowed the United States to begin viewing these two communist nations separately when it came to threat analysis. Building a ballistic missile defense system that was Chinese-specific was considered plausible, even after most U.S. defense analysts agreed that trying to put in place a similar system to counter the Soviets would be ineffective and cost-prohibitive.

The allure of a ballistic missile defense system had been around since the dawn of the missile age. In 1955, the U.S. Army had begun research and development work on the Nike Zeus antiballistic missile (ABM), but it was never deployed. President Eisenhower decided in 1959 to keep the Nike Zeus program alive as a pure research-and-development effort, which by January 1963 had evolved into what was known as the Nike X system. But whereas Nike X represented a viable ABM response based upon Soviet strike capabilities that existed pre-ABM, it was not a system that took into account what the Soviets would do to counter it.

It was this cause-and-effect relationship between defensive and offensive weapons that led two top-level Pentagon scientists, Jack Ruina and Murray Gell-Mann, to write a 1964 paper titled “BMD and the Arms Race.” The main thesis of the Ruina/Gell-Mann paper was that ABM systems were inherently destabilizing and should not be pursued. The best way to control the arms race between the Soviet Union and the United States, the paper stated, was to limit ABMs.

Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara concurred, concluding that ABMs undermined arms control and encouraged an arms race because ABMs by their very nature called into question the assured destruction capabilities of the other side, having the potential to lead to a massive arms race as each side increased its offensive strike capability to overcome the defensive characteristics of a given ABM system.

The A-35 ABM being test fired

In the early 1960s, the Soviets had been making strides toward fielding a viable ABM system of their own. In early 1961, a V-1000 missile was used to shoot down a SS-4 intermediate-range missile using a conventional high-explosive warhead, marking the first time in the world that a genuine anti-ICBM capability had been tested. The Soviets began installing V-1000 sites around the Estonian capital of Tallinn, and later around Leningrad, with installation completed in 1962. However, these sites were dismantled in 1964, when the Soviets began fielding the A-35 ABM system around Moscow.

Designed to protect the Soviet capital from single-warhead Titan II and Minutemen II missiles, the A-35 was a three-stage missile with a 300-kiloton warhead possessing a range of some 300 kilometers. The system’s manually directed radars reduced its efficiency, and it soon became obvious to Soviet military planners that the A-35 ABM system as designed was ineffective.

The perception of a growing Soviet ABM capability had led to McNamara’s Counterforce strategy (also known as the “Athens Doctrine, named after the May 5, 1962, meeting of NATO ministers in Athens, Greece, where McNamara detailed the new strategy) coming under closer scrutiny from none other than McNamara himself. The Counterforce strategy held that the first salvo of nuclear weapons launched by the United States in retaliation against a Soviet nuclear attack would be targeted against Soviet military forces (missile silos, bomber bases, and so forth) instead of Soviet cities. A certain portion of U.S. nuclear launch capability would be held back for potential use against Soviet military, industrial, and civilian targets, if needed. The key to such a new strategy rested with survivable missile systems, such as the silo-based Minuteman and the submarine-launched Polaris. Counterforce became the U.S. nuclear doctrine, and the planning guidance for SIOP-63—which went into effect in June 1962—reflected this thinking.

Misperceptions existed in the public sector that the No Cities targeting approach of the Counterforce strategy somehow made nuclear war more feasible. Furthermore, as the Air Force expanded the number of targets it needed to strike in order to achieve a genuine Counterforce capability, it began to demand even more nuclear weapons and vehicles to deploy them.

The Counterforce strategy brought with it an assumption that there would need to be an even larger air defense capability (to defend against Soviet bombers ostensibly launched on their own “counterforce” sorties) and missile defense (to defend against Soviet ICBMs targeting American nuclear forces). All of this led to increased military spending, which the Johnson administration could ill afford. When combined with the ongoing negative reaction to the Athens Doctrine from the Soviets and America’s NATO allies, McNamara had no choice but to turn to a strategic deterrence strategy of “Assured Destruction,” defined by McNamara as “to deter deliberate nuclear attack upon the United States and its allies by maintaining a highly reliable ability to inflict an unacceptable degree of damage upon any single aggressor, or combination of aggressors, even after absorbing a surprise first strike.” In short, Assured Destruction existed when the United States maintained the capability to absorb the full brunt of a Soviet nuclear surprise attack and still retaliate with a force guaranteed to destroy 20 to 25 percent of the Soviet Union’s population and 50 percent of its industrial capacity.

Assured Destruction, which soon morphed into “Mutually Assured Destruction,” or MAD, retained as a working principle the concept of “damage limitation.” This concept had American nuclear forces targeted in such a manner as to reduce the damage any Soviet nuclear attack might inflict on American population and industrial centers by attacking and diminishing the strategic offensive nuclear forces of the Soviet Union. But even this concession to the original Athens Doctrine was soon de-emphasized by McNamara out of concern that the Air Force would turn damage limitation into a genuine first-strike capability.

The Titan !! ICBM being launched from a silo

By the end of 1964, McNamara had set the strategic missile strength of the United States at 1,054 missiles (1,000 Minuteman missiles and 54 Titan II missiles) and 656 Polaris missiles on 41 submarines. As the Minuteman capability stood up, the original workhorse of the U.S. ICBM force, the Atlas missile, began to be phased out. The Air Force was not pleased with the limitation on a Minuteman force it once envisioned as being 10,000 in number. However, technology soon intervened in a way that forever changed the calculus of mass destruction.

Ironically, it was the Navy, and not the Air Force, that was initially responsible for the innovation in question: multiple re-entry vehicles (MRVs) in which a single delivery system, or missile, could carry more than one warhead. The accuracy of the Polaris A-3 at its maximum range of 2,500 miles was such that it was only useful as an area weapon. In order to increase kill probability, and to saturate any ABM system that might be deployed around a given target, the Polaris A-3 missile was deployed with a clam-shell multiple re-entry vehicle system, which carried three warheads underneath a re-entry shroud. Each warhead would be ejected by use of a small rocket motor, allowing for a given target area to be covered by three overlapping explosions.

When the USS Daniel Webster took up its initial operational patrol in the Atlantic Ocean on September 28, 1964, the Polaris A-3 MRV was operational. This was followed on December 25, 1964, by the USS Daniel Boone when it began its Pacific Ocean patrol. The Soviet landmass was now fully covered by the Polaris A-3 missile, making it a critical component of the U.S. deterrent arsenal.

Although the three-warhead MRV of the Polaris A-3 was designed to saturate a given defense, it still was operated on the premise of one target, one missile. In order to increase the effectiveness of an MRV missile, one would need to add what were known as penetration aids, or missile decoys. But even this did not change the one missile, one target equation. Missile designers experimented with the idea of maneuvering the “bus,” or vehicle that held the warheads. By doing this, and by controlling the timing of each warhead’s release, each warhead could be independently targeted.

Thus was born the concept of the MIRV, or multiple independently targeted re-entry vehicle. Now each MIRV-capable missile became a force-multiplier, the missile-equivalent of however many MIRVs with which it was equipped. MIRVs were not developed as a response to Soviet ABMs, but once the capability to overwhelm ABM defenses was identified, the MIRV became the perfect weapons system.

However, though MIRVs were a proper response to a Soviet nationwide ABM system, there was in fact no need for MIRVs if the Soviets didn’t have a viable ABM system, which was the case in 1965. Secretary of Defense McNamara understood that if American MIRVs could overwhelm a Soviet ABM defense, then in due time Soviet MIRVs would likewise overwhelm any American ABM defense. Nonetheless, MIRVs became the weapon of choice for everyone involved in the strategic targeting business. For the Air Force and Navy, the limitations imposed by McNamara’s 1,054/656 missile cap were now meaningless because MIRVs allowed the number of deliverable warheads to be increased without changing those numbers.

As MIRVs became more accurate, each warhead could be targeted on a single missile silo, creating not only a potent Counterforce capability but a viable first-strike weapon as well. As MIRVs made land-based systems more vulnerable, they in turn enhanced the importance of submarine-launched ballistic missiles, not only as a retaliatory force but also as a backup to the Counterforce/first-strike capability of ICBMs.

During the period of 1965–1966, MIRVs were very much a theoretical weapon. However, the ascension of MIRVs as the new “wonder weapon” drove the strategic planning for future weapons acquisitions, and as such pushed the Soviet Union and the United States closer to the edge of a new, expensive, and dangerous, phase of the arms race. McNamara commissioned a study concerning ABM employment and viability under the direction of Army Major General Austin Betts. The Betts Panel examined potential Nike X deployment locations, production schedules and costs, system effectiveness, national strategic objectives, and cost effectiveness in terms of both the current Soviet ICBM threat as well as any potential improvements the Soviets might make in response to an American ABM system.

A Nike X ABM being test launched

The critical factor behind whether or not the Nike X was deemed a viable system was the degree to which it reduced the Assured Destruction aspect of the Soviet strategic nuclear force. If the Nike X could prevent the Soviets from achieving the criteria set forth by McNamara for Assured Destruction (i.e., preserving more than 75 percent of the U.S. population and more than 50 percent of America’s industrial capacity), then the United States would achieve strategic dominance because it would, theoretically at least, emerge in a superior position from a full-scale nuclear exchange with the Soviet Union.

McNamara had earlier commissioned a study to be conducted by the Office of Research and Engineering. Air Force Brigadier General Glen Kent headed the study. Kent organized his study so that two factors could be assessed: first, what the damage to the United States would be from a determined and adaptive Soviet attack; and second, what would constitute a proper allocation of resources among various entities (civil defense, Nike X ABM, Counterforce attacks by Minuteman missiles, antisubmarine warfare targeting Soviet missile submarines, and air defense against Soviet bombers) in order to limit damage against the United States.

Kent’s study concluded that in order to obtain a 70 percent survival rate for the American population against then-current Soviet forces, the United States would need to spend $28 billion. However, if the Soviets then responded to the American damage-limiting actions by deploying more ICBMs and SLBMs, then the United States would need to expend even more money to sustain the 70 percent survivability factor, at a cost of some $2 dollars spent on defense to every $1 spent on offense.

Because a 70 percent survivability rate meant that some 60 million Americans were destined to die, this tack was politically unacceptable. Yet when efforts were made to improve the survivability factor to 90 percent, it was found that the exchange ratio (the amount the United States would have to spend to limit damage compared to the amount the Soviets would have to spend to create damage) rose to 6:1 in favor of the Soviets.

In short, Kent concluded, it was always cheaper to create damage than it was to limit damage. The destruction generated by nuclear weapons, combined with the vulnerability of modern urban-industrial society, meant that neither the United States nor the Soviet Union could avoid national destruction in the event of an all-out nuclear conflict. This was even further underscored when one factored in that an attacker was able to modify its weapons and tactics after the defender had invested and deployed its defenses. McNamara, thanks in no small part to Kent’s study, determined that damage limitation as a national strategy simply would not work.

Instead of seeking to unilaterally limit damage through new weapons and strategies, the best option for both the United States and the Soviet Union would be to enter into negotiated treaties to curtail nationwide ABM defenses and limit the deployment of offensive nuclear forces. But, as was far too often the case, national security considerations alone did not suffice to make the case.

Politics reared its ugly head.

George Romney

Michigan Governor George Romney, by 1966 considered a leading Republican challenger to Lyndon Johnson in 1968, was being very vocal about the existence of an “ABM gap,” hoping to repeat the success that the so-called missile gap had created for John Kennedy in 1960. Romney made a point of the ABM gap during an interview on Meet the Press. Melvin Laird, head of the GOP Congressional Committee, was likewise making it clear that the ABM issue would be a focus of the Republican Party challenge to the national security policies of the Johnson administration.

Romney and Laird had support from hawks in the U.S. Senate, such as Republican Strom Thurmond, but also including a number of prominent Democrats (e.g., Henry “Scoop” Jackson and Richard Russell) when it came to the early deployment of an ABM system. Both Thurman and Russell had long records of supporting a strong defense against a Soviet threat, whether real or perceived.

Jackson’s motivations were more complicated: as the senator from Washington State, Jackson had become known as “the senator from Boeing” due to his unwavering support of the Seattle, Washington–based company. Boeing was a major contractor involved in the ABM system.

Secretary of Defense McNamara had opened the door for congressional action when, in his annual military posture statement presented to the House of Representatives in early 1966, he noted that a small ABM system could provide a “highly effective defense” against any ballistic missile attack launched from China. McNamara had made this statement in order to head off congressional pressure, noting that there was no rush to field such an ABM system because any viable Chinese missile threat would not materialize for many years.

Congress was considering three options for an ABM system: a “thick” nationwide system, costing some $40 billion and designed to provide maximum protection against a Soviet missile attack; a missile protection option designed to defend ICBM bases; and a “thin” nationwide system designed to protect against a Chinese-style attack and projected to cost around $5 billion. Based upon the work done by General Kent, McNamara was strongly opposed to either the thick defense or the equally expensive ICBM base defense, primarily because he believed the Soviets would be able to easily overwhelm these defenses with missiles then in development.

However, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, alarmed by intelligence reports detailing the deployment of Soviet ABM systems around Tallinn, Leningrad, and Moscow, together with other reports indicating the Soviets were modernizing their ICBM force, believed that national security could not brook a continued delay in fielding a national ABM defense. In 1966, Congress, against the desires of the Johnson administration but with the full support of the JCS, had authorized and appropriated some $167.9 million to produce the Nike X ABM. But President Johnson and Secretary McNamara, by the end of 1966, had refused to spend these funds.

The political pressure on Johnson was starting to heat up. The JCS desires for immediate deployment of an ABM system were about to be made public by the Republicans in Congress, as was the intelligence about the deployment of a Soviet ABM system. Lyndon Johnson could ill afford to continue to delay on the issue of fielding an American ABM system. It looked as if McNamara was going to be overruled on this issue.

President Johnson meets with McNamara and the Joint Chiefs at his Texas ranch

Then, showing considerable political savvy, McNamara maneuvered back. In a series of meetings with Lyndon Johnson, held at the Johnson ranch in Austin, Texas, on November 3 and 10, 1966, McNamara pressed home his case that an ABM system simply would not work, was excessively expensive, and would dangerously destabilize the strategic balance between the Soviet Union and the United States.

Following the November 10 meeting, McNamara pre-empted the Republicans in Congress by holding a press conference at which he revealed details about the Soviet deployment of an ABM system and his own belief that ongoing U.S. efforts to improve its offensive nuclear capabilities, namely the deployment of the Minuteman III ICBM and the new Poseidon SLBM, would represent a more-than-adequate response.

McNamara again traveled to Johnson’s Austin ranch on December 6, 1966, this time joined by Deputy Secretary of Defense Cyrus Vance; the president’s special assistant for national security affairs, Walt Rostow, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The ostensible purpose of the meeting was to review the 1968 defense budget, due to be presented to Congress in February 1967. But the centerpiece of discussion was the issue of funding to produce an ABM system. The JCS was pressing hard for the funding and was equally opposed by McNamara and Vance. Rostow took the side of the Joint Chiefs, and it looked for a moment as if Johnson was going to overrule his secretary of defense.

McNamara interceded one last time, stating unequivocally that building an ABM system was absolutely the worst decision the United States could make at this juncture. The proper course of action was to expand the offensive strike capability of the United States in order to overwhelm the Soviet ABM system. This would obviate the Soviet defense (at great expense to the Soviets) while at the same time making sure the United States did not make the same blunder.

Recognizing that Congress had already approved funding for the ABM system, McNamara proposed that the 1968 budget allow for a small amount of money for ABM procurement. However, McNamara then wanted to inform Congress that none of this money would be spent, and no final decision would be made about deploying an ABM system, until the United States made every possible effort to negotiate an arms control agreement with the Soviets that banned ABMs and limited offensive nuclear forces.

Johnson agreed to this compromise approach. He directed Secretary of State Dean Rusk to begin outreach to the Soviets for the purpose of initiating dialogue on arms reductions and limitations. The president even tried to assist this effort when he revealed in a March 1967 meeting with educators in Nashville, Tennessee, that the United States had an extensive satellite reconnaissance program and that from it the United States was able to know exactly how many ICBMs the Soviets had. “I wouldn’t want to be quoted on this,” Lyndon Johnson said, knowing full well he would be quoted, “but we’ve spent thirty-five or forty billion dollars on the space program. And if nothing else had come out of it except the knowledge we’ve gained from space photography, it would be worth ten times what the whole program has cost. Because tonight we know how many missiles the enemy has and, it turned out, our guesses were way off. We were doing things we didn’t need to do. We were building things we didn’t need to build. We were harboring fears we didn’t need to harbor.”

But even this “slip of the tongue” did not produce results; the Soviets, having invested so heavily in seeking nuclear parity, simply refused to talk about arms reductions. There were several reasons behind the Soviet obstinacy over arms limitations talks, the main one being that the United States was not seen as an honest partner when it came to arms reduction talks.

On June 19, 1967, Soviet Premier Aleksei Kosygin was in New York to attend an emergency session of the UN Security Council convened to address the consequences of Israel’s Six-Day War against its Arab neighbors. Once these meetings were finished, Soviet and American officials conspired to organize an unplanned summit between President Johnson and Premier Kosygin. The Americans preferred a meeting held in Washington, while the Soviets preferred New York City. As a compromise, a decision was made to meet at Glassboro State College in New Jersey, a location almost exactly half-way in between.

Alexei Kosygin (left) meets with Lyndon Johnson (right)

The meeting was intended to provide a forum for the discussion of serious arms control issues. At the initial introductory meeting on June 23, 1967, President Johnson told Kosygin that in the three years he (Johnson) had been in office, there were no new arms control treaties between the two nations. Johnson’s primary purpose in convening the Glassboro Summit was to engage the Soviets in a meaningful dialogue on arms control to head off a spiraling arms race. The issue of ABMs was addressed in detail. But ultimately Kosygin saw little hope of genuine discussions so long as the Vietnam War continued and the situation in the Middle East remained unresolved. The Glassboro Summit ended shortly thereafter with nothing having been accomplished.

The lack of results from the Glassboro Summit represented a setback to the Johnson administration’s ambitions to pursue a meaningful arms control agenda. There were almost immediate consequences for this failure. Upon their return to Washington, Johnson and McNamara met with the Joint Chiefs of Staff, where it was agreed that in the face of the Soviet refusal to discuss the ABM issue, the United States would initiate immediate action to expand its offensive strike capability.

The cheapest and most effective way to do this was to move forward with the development and deployment of MIRVs. However, McNamara recognized that this measure had inherent risks, namely that if the Soviets followed suit and deployed its own MIRV capability, then the United States would find itself on the receiving end of a more potent Soviet arsenal, magnified by the reality of the larger payload capability of the Soviet missiles. Therefore, even though the United States would develop a MIRV capability, a final decision to deploy MIRVs would be withheld pending a renewed effort at negotiating a treaty to ban ABM defenses. If such a treaty could be implemented, then the MIRV program would be terminated.

Like the United States, the Soviets were assessing their potential enemy’s strategic capabilities and making their own adjustments. The Soviets were following the deployment of the Minuteman missile with great interest. They knew that the Minuteman operated as a wing of 150 missiles. Each wing consisted of three squadrons, each composed of five flights containing ten missiles each stored in an unmanned launch facility, or silo. The silos were separated from one another by three miles, which also represented the distance the silos were from their respective launch control centers (LCC).

In order to successfully target the Minuteman missile complex, the Soviets would either have to saturate the area with huge warheads in the large megaton range, hoping to collapse the silos, or target each silo independently with smaller warheads requiring a much greater degree of accuracy. The Soviets soon realized that the weak link in the Minuteman system was the LCC. If the LCC could be taken out, then this achieved the same effect as taking out ten missiles in their silos.

If the Soviets were to embark on a Counterforce strategy of their own, then they would need a missile capable of carrying a warhead large enough to defeat a hardened LCC and accurate enough to get within .5 nautical miles of the target—a circular error of probability, or CEP, of about 925 meters. Soviet recognition of this operational requirement led to their development of the SS-9.

The SS-9 was an “ampulised” missile, meaning that it would be loaded into its missile silo as a sealed round of ammunition, completely fueled and ready to fire. In this mode, the SS-9 could guarantee being able to launch for a period of at least five years. It would be transported to its silo, loaded in, fueled, and then sealed and left unattended. Like the Minuteman, the SS-9 silos were to be separated from one another—but by eight to ten kilometers, making them difficult to target.

An SS-9 being test fired

Whereas the SS-9 ICBM was designed as a Minuteman-killer, the Soviets still needed an equivalent ICBM to match the Minuteman in performance (i.e., the ability to be quickly launched). The answer came from the design bureau of Vladimir Chelomei in the form of the SS-11, a lightweight ICBM that ultimately would be deployed in more numbers than any other Soviet ICBM. The SS-11 was designed to be silo-launched as a certified round of ammunition and was able to be stored, fully fuelled and ready to launch, for up to five years. The Soviet Union was in such a hurry to match the Minuteman capability of the United States that secret survey teams were already constructing silo locations for the SS-11 even before the missile was initially tested. The SS-11 carried a 1.1-megaton warhead, but its accuracy was so poor as to limit its effectiveness to “soft” targets, like cities and major industrial areas.

It was a moment that Lyndon Johnson would not be able to share with his long-time secretary of defense, Robert McNamara. Since 1966, McNamara had become more and more controversial in the face of his opposition to both the president and the Joint Chiefs of Staff about the war in Vietnam. McNamara’s resistance to an ABM system also alienated him from his military counterparts.

On November 29, 1967, with a contentious political season approaching, President Johnson had pulled the plug, announcing that McNamara would be resigning from his position as secretary of defense and moving on to become president of the World Bank. McNamara left office on February 29, 1968. For his seven years of dedicated service, President Johnson awarded him both the Medal of Freedom and the Distinguished Service Medal.

McNamara was replaced by Clark Clifford, who took over in March 1968. Unlike McNamara, Clifford was not a proponent of arms control; he wanted to limit any initial steps involved in arms negotiations to simple administrative and procedural functions and await a specific Soviet proposal. Clifford viewed any commitment made by the United States up front as concessions preceding the negotiations, something he contended was never a wise move in the field of diplomacy.

But Lyndon Johnson wanted more. His time as president was running out. Because he had not been elected president in 1960, Johnson was not affected by the Twenty-Second Amendment to the United States Constitution, limiting a president to two terms in office. It was widely assumed that Johnson, despite being heavily criticized over the conduct of the Vietnam War, would seek reelection. However, a strong showing by antiwar candidate Eugene McCarthy during the New Hampshire primary on March 12, 1968, followed four days later by Robert Kennedy’s announcement that he would challenge Johnson for the nomination of the Democratic Party, compelled Johnson to rethink his ambition. (Bobby Kennedy’s bid for election was tragically cut short by an assassin’s bullet on June 5, 1968.)

Lyndon Johnson announces he will not seek reelection

On March 31, 1968, Lyndon Johnson addressed the American people in a live televised speech, during which he announced that he was ordering the suspension of aerial bombing attacks on North Vietnam in favor of peace negotiations. Johnson concluded his presentation with a stunning statement: “I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your President.”

Johnson was in poor health, and he and his family were very concerned that he might not survive another term in office. Thus liberated from the constraints of a national election, Lyndon Johnson turned to thoughts of his legacy. Worn down by Vietnam, Johnson was intent on closing out his tenure as president with far-reaching arms limitation agreements. Lyndon Johnson had sought arms control treaties even prior to his decision not to seek a second term. On January 22, 1968, Johnson had sent a letter to Soviet Premier Kosygin in which he proposed early talks on strategic missile controls.

Having not heard back from the Soviets, on March 16, 1968, Secretary of State Rusk instructed the U.S. embassy in Moscow to seek a favorable response to the president’s letter. The U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union, Llewellyn Thompson, met with Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko on March 26, 1968, to discuss Johnson’s proposal, only to be told that the Soviet government, though attaching great importance to the idea, was still studying the proposal.

By May 2, 1968, the continued Soviet silence prompted President Johnson to write another letter, noting his concern over the “necessity to initiate meaningful discussion as soon as possible,” noting that “each passing month increases the difficulty of reaching agreement on this matter as, from a technical and military point of view, it is becoming more complex.” Johnson told Kosygin that it was important that they be able to announce to the world that “they have agreed to commence bilateral negotiations on an agreement to limit strategic offensive and defensive missiles within a specific time from the date of the announcement.”

On May 17, 1968, the Soviets responded indirectly, having a diplomat state that Moscow was still considering the U.S. proposal that talks begin. Then, on June 21, 1968, Aleksei Kosygin finally responded in a letter of his own to Johnson. The Soviet premier told Johnson that the Soviets “attach great importance to these questions, having in mind that they should be considered together, systems for delivery of offensive strategic nuclear weapons as well as systems for defense against ballistic missiles. All aspects of this complex problem are now being carefully examined by us, and we hope that before long it will be possible more concretely to exchange views with regard to further ways of discussing this problem, if of course the general world situation does not hinder this.”

On July 1, 1968, both nations simultaneously announced that they agreed to meet in the “nearest future” to discuss strategic nuclear arms limitations, as well as limitations on ballistic missile defense. Johnson decided he would up the ante by increasing the pressure on the Soviets to come to the negotiation table. On July 2, Dean Rusk met with Soviet ambassador to the United States Anatoliy Dobrynin and informed him that President Johnson wanted another summit meeting with his Soviet counterpart in the near future.

President Johnson’s desires for an arms control agreement did not, however, directly translate into an agreed upon position within the U.S. national security hierarchy. Secretary of Defense Clifford was concerned about on-site inspection and verification regimes that would be associated with any such agreements. Others wanted to preserve the ability to maintain qualitative force improvements, both for a nuclear warhead for the Sentinel ABM but also for any future MIRV warhead.

Under pressure from the White House, a policy paper was prepared on July 31, 1968, that outlined the basics of an agreed-on U.S. position on strategic arms limitations: a freeze on ICBM, MRBM, and SLBM submarines; a ban on deploying mobile ICBM systems; a ban on mobile ABM systems; and an agreement to limit any ABM system to a specific number of fixed launchers and associated radars.

A final meeting of the principal players tasked with drafting a U.S. position was held on August 7, 1968. It soon became clear that there were many issues that lacked resolution. The Joint Chiefs were very concerned about cheating scenarios involving mobile ICBMs. Dr. Ivan Selin, representing Clifford, responded that the Soviets would only be able to field 200–300 mobile ICBMs without being detected, and the U.S. nuclear force was able to withstand a surprise attack from thousands of nuclear warheads. This kind of cheating scenario, in Selin’s opinion, was not possible. Furthermore, “Our forces are so large and diverse,” he stated, “that our assured destruction capability is relatively insensitive to most forms of qualitative improvements, cheating or abrogation scenarios.”

US MIRVs reentering the atmosphere

In his opinion, MIRVs represented a far greater threat than mobile ICBMs. At this point, Adrian Fisher of ACDA interjected that he thought the Soviets might seek to ban MIRVs, a possibility that Selin conceded had not been considered by the Pentagon. The two MIRV systems being considered by the United States, the Minuteman III and the Poseidon, were due to be flight tested in mid-August. Secretary of State Rusk asked if these flight tests should be postponed until after the arms limitations talks were held. However, the consensus among attendees was that the tests should go forward as scheduled. This was a critical decision because by agreeing to flight tests of an MIRV capability, the United States had made it all but impossible to ban MIRVs once negotiations began.

The final U.S. position was submitted to the president on August 15, 1968. In covering memorandums, both Rusk and Clark offered their support for the position paper, noting that the United States would maintain its deterrent posture, leave no doubt as to the adequacy of the deterrent, be confident that the deterrent could not be eroded by one or more powers alone or in combination, would maintain a damage-limiting capability, and be able to prevent other (non-Soviet) nuclear powers from threatening the agreement.

All that was needed was a summit.

Presidential politics intervened, in the form of the Republican nominee, Richard Nixon, asking to be received in Moscow. The Soviets agreed, prompting Secretary of State Rusk to ask Moscow if the Soviets might likewise agree to meet the man who was still the president. The Soviets postponed the meeting with Nixon. Then, on August 19, the Soviets finally agreed to receive Johnson in Moscow on October 15, or any other date close to that time. Elated, President Johnson prepared to make an announcement concerning his trip and the goals of limiting strategic arms through reduction talks.

At this portentous moment, unexpected events intervened. On August 20, 1968, Soviet tanks rolled into Czechoslovakia. The series of reforms initiated in the country since Alexander Dubček had replaced the Czechoslovakian Communist Party leader, Antonin Novotny, in the spring of 1968 had proven to be too much for the Soviet leadership to accept. Czechoslovakia’s neighbors, East Germany and Hungary, were nervous about the liberalization of what was being called “Prague Spring” and were pressuring the Soviets to do something. On July 14 and 15, the Soviets hosted a Warsaw Pact meeting, without Czech involvement, followed on July 23 by the Soviets announcing a large military exercise, “Nieman,” which served as a cover for the deployment of hundreds of thousands of troops and more than 7,000 tanks to the Czech border regions.

The final decision to invade Czechoslovakia was made between August 15 and 17, with Soviet Communist Party chair Leonid Brezhnev sending a letter to Dubček on August 19, the same date the Soviets extended the invitation to Johnson to visit Moscow.

On August 20, President Johnson convened a cabinet meeting to discuss the status of the strategic arms reduction talks. The National Security Council agreed with Johnson’s calling the Soviet invasion an “aggression” and agreed that thus there could be no summit with the Soviets on arms reduction, noting that such a meeting might be interpreted by the Soviets and others as the United States condoning the Soviet action. Ambassador Dobrynin was summoned by Rusk, who informed him of the president’s decision.

Soviet tanks roll into Prague, August 20, 1968

There was some effort to restart the talks, with the Soviets agreeing to a meeting in mid-September 1968 to set out an agenda. But Johnson had taken the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia as an insult. As Rusk told Ambassador Dobrynin on September 20, 1968, during a lunch meeting, “the coincidence of actions [the invasion of Czechoslovakia and agreeing to arms reduction talks] was like throwing a dead fish in the face of the President of the United States.”

Time had run out on the Johnson administration for accomplishing meaningful arms control with the Soviets. The presidential elections of November 5, 1968, saw Republican Richard Nixon defeat Vice President Hubert Humphrey. With a new administration due to take power, there was no incentive for the Soviets to sit down and talk, even on an issue as important as arms reductions.

History shows that under President Johnson’s leadership, so much could have been accomplished in the field of disarmament, and so little was.

(I will be travelling to Russia in March to continue my efforts to promote arms control and better relations between the US and Russia. As an independent journalist, I am totally dependent upon the kind and generous donations of readers and supporters to underwrite the costs associated with such a journey (travel, accommodations, meals, studio rental, hiring interpreters, video production and editing, etc.) I am grateful for any support you can provide.)

oooooo

An ABM Primer, Part Two: Closing the Deal

https://substack.com/@realscottritter/note/p-186496427?utm_source=notes-share-action

An ABM Primer, Part Two: Closing the Deal

History shows that there is an inherent and necessary link between strategic nuclear arms limitations/reductions and ABM. This lesson is being ignored by letting New START expire in favor of ABM.

Feb 02, 2026

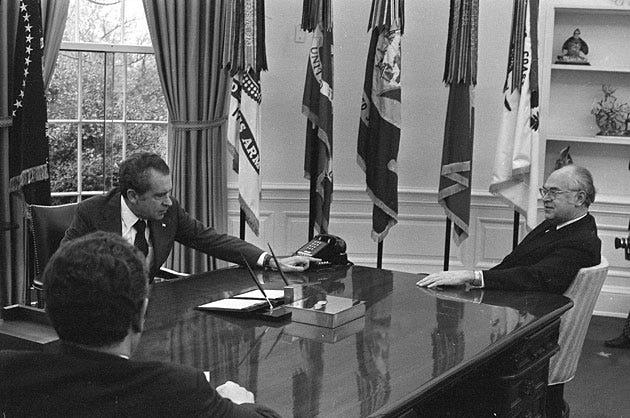

Richard Nixon (left) meets with Anatoliy Dobrynin at the White House

(Note: This article contains material from my book, Scorpion King: America’s Suicidal Embrace of Nuclear Weapons from FDR to Trump, published in 2020 by Clarity Press. This is the first of a three-part series on the ABM Treaty, which served as the foundation for arms control in the nuclear era and without which there can be no meaningful progress in reviving arms control post New START.)

Arms control became a top policy priority for the newly-elected President Richard Nixon. On February 17, 1969, Soviet ambassador Anatoliy Dobrynin met with President Nixon and informed him that the Soviet Union was prepared to enter wide-ranging negotiations on a number of issues. The Soviet objectives for such talks were to enforce the nonproliferation treaty, end the war in Vietnam, settle the conflict in the Middle East, recognize the status quo in Europe, and curb the arms race through strategic arms reductions.

Dobrynin asked Nixon when the United States would be ready to begin these talks. Nixon was noncommittal, saying arms reduction discussions required considerable preparation. The president, bypassing the secretary of state (whose job it usually would be), asked Dobrynin to bring up the issue of talks with his national security adviser instead.

So began the Dobrynin-Kissinger channel, a highly confidential mechanism for a candid “exchange of opinions” between the United States and the Soviet Union. Once Kissinger and Dobrynin could agree in principle about the issues in question, the problem would then be turned over to the appropriate diplomatic channel for a “detailed working review.”

On the issue of arms control negotiations, the problem at hand was one of timing, Kissinger explained to Dobrynin. The key matter was the link between when such talks should begin and the deployment of an antiballistic missile (ABM) system by the United States. Kissinger stressed that there were differences between the State and Defense Departments over this—State wanted talks to begin as soon as possible and not be subject to military constraints, whereas Defense believed practical decisions about the deployment of an ABM system should not be made contingent upon arms control talks.

Kissinger was surprisingly honest and open with Dobrynin about how much time it would take to get arms reduction talks on track. But he had been less so when it came to attributing the reasons for this delay. Kissinger had long viewed the Soviet push for arms reductions talks as a device used by Moscow to regain credibility lost after their move against Czechoslovakia in August 1968. Kissinger also believed that the Soviets intended to use such talks to divide NATO, in addition to stabilizing the strategic balance.

Anatoliy Dobrynin (left) meeting Henry Kissinger (right)

Both Nixon and Kissinger believed in the principle of linkage, where one policy objective would be linked with others, and not treated in isolation, when it came to foreign policy. In the case of arms reduction talks, both Nixon and Kissinger believed that they should not Peace through Strength 185 be pursued in isolation but rather be linked to the Soviet Union’s ability to assist the United States in Vietnam and the Middle East.

The war in Vietnam was an ever-present reality as well as a source of policy frustration for the Nixon administration. The year 1968 had been the bloodiest one yet for the American forces fighting in Southeast Asia, and Nixon was determined to bring the war to a close. Within the Nixon administration, many policy advisers blamed the continued Soviet military, political, and economic support for the North Vietnamese government for the difficulty the United States faced in South Vietnam.

Using his linkage philosophy, in mid-April 1969, Kissinger told Ambassador Dobrynin that U.S.-Soviet relations were at a critical phase and that Vietnam was the key to resolving differences in other areas, such as arms control. Kissinger proposed sending Cyrus Vance—who had been leading the U.S. delegation to the Paris peace talks since 1968—to Moscow to initiate arms reduction talks and, at the same time, open discussions with the North Vietnamese. Dobrynin was evasive, and Vance never made the trip.

The Soviets, however, continued to send signals that they were prepared for arms reduction negotiations. On May 1, 1969, the Soviets canceled their usual military parade. Instead, Leonid Brezhnev spoke from atop Vladimir Lenin’s tomb, calling for peaceful coexistence with the West. On July 10, 1969, Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko addressed the Supreme Soviet, calling for closer relations with the United States, declaring that “We for our part are ready.”

This was the best the Soviet Union could do.

Domestically, Brezhnev was in the midst of a bitter power struggle with Aleksei Kosygin. Kosygin had attempted to implement economic reforms in the post-Khrushchev era by shifting the emphasis in the Soviet economy from heavy industry and military production to light industry and the production of consumer goods. Brezhnev did not support this policy and stymied Kosygin’s reforms. He was also concerned about Kosygin’s preeminence in foreign affairs and was gradually trying to insert himself in that arena. By the end of the decade, Brezhnev would become the unquestioned leader of the Soviet Union, but in the first half of 1969, he was not able to make bold moves. Signaling his resolve to meet an American initiative was the best he could do.

Aleksei Kosygin (left) and Leonid Brezhnev (right)

Linkage wasn’t the only issue that hindered movement on arms reduction talks. For President Nixon, American military strength was the basis for a successful negotiation. As such, the United States could ill afford to enter any meaningful negotiations from a position of real or perceived weakness but rather was required to “look tough.”

As had been the case when the Johnson administration had begun constructing a unified position on arms reduction talks, two issues proved to be particularly sticky when it came to achieving consensus on how best to proceed: multiple independently targeted re-entry vehicles (MIRVs) and antiballistic missile defense. The United States had a significant lead over the Soviet Union when it came to MIRVs. Initial testing of an MIRV-equipped missile had begun in August 1968, and the Navy and Air Force were scheduled to undergo final testing in May 1969 for both the Minuteman and Poseidon missiles. These tests were scheduled to be completed by July 1969.1

The Soviets lagged behind, having tested an MRV-equipped missile for the first time in September 1968. However, the Soviets had fielded the giant SS-9 missile, which with its ability to deliver large payloads (defined in arms control terms as “throw weight”) meant that if the Soviets were to develop and test their own MIRV capability, they would soon be able to overwhelm the United States in terms of the numbers of nuclear warheads it could deliver, even if the number of missiles remained unchanged.

This fact had not gone unnoticed by analysts in the United States. In a June 1969 memo, George Rathjens and Jack Ruina warned Kissinger that a decision to go ahead with MIRV tests “probably also implies the eventual abandonment of the Minuteman missiles by the United States,” because the United States would need to replace the small Minuteman with a missile possessing a throw weight equal to or exceeding the SS9.

This was the arms race everyone feared. Both the Department of Defense and the Joint Chiefs of Staff supported the development and deployment of MIRVs. American strategic nuclear targeting centered on having the MIRV-equipped Minuteman III missile (which would carry three MIRVs) and the new Poseidon missile (which would carry twelve MIRVs). Instead of banning MIRVs, the Department of Defense wanted U.S. arms reduction talks to focus on limiting missile throw weight, thereby limiting future Soviet MIRV potential.

The president came down on the side of having MIRVs. Nixon released secret information about Soviet MRV tests, claiming that analysis conducted by the United States concerning impact patterns of the missiles showed that they were being optimized to strike U.S. Minuteman silos.16 Survivability of the U.S. deterrent, therefore, hinged on the United States equipping its own forces with MIRVs to ensure that enough retaliatory capability survived any Soviet attack.

By summer 1969, the Air Force awarded a contract for the manufacture of thirty-eight MIRV missiles. From an arms control perspective, this was a critical move. Any ban of MIRV testing would be relatively easy to verify— since satellite imagery and electronic intercepts would suffice as a means of monitoring. A ban on MIRV deployment, on the other hand, would require intrusive on-site inspection-based verification measures neither the Soviets nor the Americans would agree to. Committing to the testing of MIRVs all but assured that they would be deployed.

Although MIRVs as a weapons system impacted any future arms reduction talks, so did the way the United States planned to utilize nuclear weapons in any conflict, MIRVs or no MIRVs. On January 27, 1969, Nixon and Kissinger—joined by Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird and chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Earle Wheeler—traveled to the Pentagon, where they were briefed on SIOP-4, the latest version of America’s nuclear war plan. SIOP-4, which had basically remained unchanged in operating philosophy since mid-1966, consisted of five nuclear attack options, retaliatory or pre-emptive in nature, depending on the amount of warning time available to the decision-maker. There was also a launch-on-warning capability. All strike options involved thousands of nuclear weapons hitting Soviet military, economic, and population centers.

Helmut Sonnenfeldt, an NSC staffer who was present at the briefing, reported that President Nixon was “appalled” at the prospect of a nuclear conflict that would kill some 80 million Soviets, and at least that many Americans, as well as the fact that he, as the American chief executive, had so few choices when it came to responding to a major crisis between the United States and the Soviet Union.

The basic guidance behind the creation of the SIOP was known as the National Strategic Targeting and Attack Policy (NSTAP), which established the three core objectives of waging strategic nuclear war as being 1) to destroy nuclear threats to the United States and its allies in order to limit damage to them; 2) to destroy a comprehensive set of nonnuclear military targets; and 3) to destroy war-supporting urban and industrial targets so that 30 percent of the enemy’s population would be killed together with 70 percent of their war-fighting industry.

Following along strategic thinking in place since the Berlin crisis of 1961, the SIOP was designed to “maximize U.S. power” and “attain and maintain a strategic superiority which will lead to an early termination of the war on terms favorable to the United States and our allies.”

Derived from McNamara’s No Cities philosophy contained in his Athens’s Doctrine, SIOP-4 was simply a repackaging of SIOP-3, providing options for nuclear targets only; military targets only; and all targets, including urban areas. Kissinger was obviously frustrated by the lack of flexibility inherent in the SIOP, and shortly after receiving the briefing, called up McNamara and asked of the military, “Is this the best [you] can do?”

By the time Nixon assumed office, the United States and the Soviet Union had achieved strategic parity, and McNamara’s Assured Destruction had become Mutually Assured Destruction—MAD was its famous acronym. Both Kissinger and Nixon, after reviewing American nuclear strategy, were concerned that the Soviets in fact had achieved a greater ability to inflict harm on the United States than the United States could inflict on the Soviet Union. They also worried that this fact would embolden the Soviets when it came to confronting the United States and its allies on foreign policy matters worldwide. Nixon and Kissinger were so concerned over the Soviet Union’s potential to stand up to the United States in Europe that the president, at a meeting of the NSC on February 19, 1969, declared that “the nuclear umbrella in NATO is a lot of crap.”

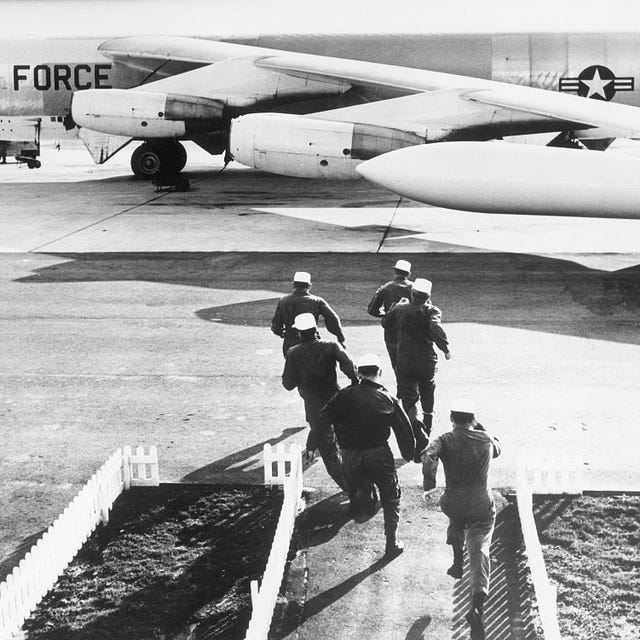

US Air Force B-52 crew scrambles to take off while on nuclear strip alert

While Kissinger wrestled with American nuclear strike plans, he was in fact satisfied with the level of American nuclear forces. Having defined the Nixon nuclear strategic doctrine as being based on the concept of “strategic sufficiency,” Kissinger believed that the current force levels based upon the existing nuclear triad (1,054 ICBMs, 656 SLBMs, a substantial strategic bomber force, and a viable ABM system) were sufficient to deter a Soviet attack. In effect, he supported the underpinnings of the McNamara nuclear posture of Assured Destruction without embracing the term.

However, Kissinger took the argument to a new level, asking if the Soviets operated on an all-or-nothing approach (zero nuclear weapons or massive attack), or if they might have an option where they could fire off a limited nuclear attack, knowing that the United States would hesitate to respond because the result would be the destruction of American cities. Although his advisers argued that this was not a likely course of action for the Soviets, Kissinger asserted that the United States should be able to place the Soviets in a similar quandary. Kissinger wanted to be able to use discriminating nuclear attacks (i.e., the ability to pick and choose a range of discrete targets based upon a given scenario, as opposed to a “one size fits all” plan) as a means of getting the Soviets to back down in a crisis.

An outgrowth of these internal debates and discussions was its formal definition, in the form of National Security Decision Memorandum (NSDM) 16, “Strategic Sufficiency,” published on June 24, 1969. In it, Kissinger stated that strategic sufficiency was defined as being assured that the U.S. second-strike capability was sufficient to deter an enemy surprise attack, thus insuring the Soviets had no incentive to strike the United States first in a crisis. A key aspect to this was possessing the capability to ensure that the United States could deny the Soviets the ability to cause more damage to America in a nuclear exchange than America could cause to the Soviet Union.

This guidance underscored the emphasis both Nixon and Kissinger were placing on an ABM capability and underscored why ABM was playing such a major role (bigger than MIRVs or the SIOP) in shaping a Nixon arms control policy. It is not that Nixon conceived ABM, or even initiated its deployment; he had done neither. The decision to deploy ABM had been made during the Johnson administration. On September 18, 1967, then-Secretary of Defense McNamara had announced that the United States would begin deployment of a “thin” ABM system, known as Sentinel, intended to defeat a limited Chinese missile attack. Sentinel was also intended to reinforce American security assurances to its allies by demonstrating its deterrent capability and to protect against “the improbable but possible accidental launch of an intercontinental missile by one of the nuclear powers.”

In making his announcement, McNamara had stated that the “decision to go ahead with a limited ABM deployment in no way indicates that we feel an agreement with the Soviet Union on the limitation of strategic nuclear offensive and defensive forces is in any way less urgent or desirable.”

The Sentinel ABM Site

But McNamara had only initiated the political process to enable an ABM deployment. By the time Nixon assumed office, Sentinel was still a plan, not a reality. One factor McNamara could not have factored in when making his announcement in September 1967 was the fundamental difference between the 90th Congress, which had so aggressively funded ABM even when McNamara and Johnson didn’t ask for funds, and the 91st Congress, elected alongside Nixon, which was a product of increasing skepticism of all things military thanks to the ongoing debacle in Vietnam. Money had been allocated for Sentinel, but the new Congress was not necessarily so inclined to spend it.

On March 5, 1969, Kissinger provided Nixon with a new modified Sentinel ABM proposal designed to ease congressional concerns. First, Kissinger noted that the modified Sentinel program was not designed with modern Soviet threats in mind, namely submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBM) and a new threat, known as the fractional orbital bombardment system, or FOBs.

The SLBM, being launched close to American shores as opposed to launched from fixed bases in the Soviet Union, had a much shorter (3–15 minutes) flight time that made interception by a Sentinel-type system unlikely unless the individual crews of the Spartan and Sprint missiles were given authority at all times (i.e., pre-delegation) to launch nuclear missiles over American soil. Given the possibility of an accident, such pre-delegation was politically impossible.

FOBs presented a completely different problem set; in short, there was no defense. The goal of FOBs was to place a large nuclear warhead equipped with a de-orbited rocket stage into low Earth orbit (approximately 90 miles altitude). The warhead could theoretically approach the United States from any direction, below the altitude of any tracking radar, and be de-orbited at will, meaning no one would know when it might strike. The Outer Space Treaty, implemented in 1967, banned orbiting nuclear weapons, but it did not ban systems capable of orbiting nuclear weapons, so the Soviets exploited that loophole by never testing FOBs with a live warhead. Likewise, the Soviets never allowed the system to complete an orbit, de-orbiting the test warhead prior to one complete revolution around the Earth (hence the name “fractional orbiter”).

Another problem lay in the nature of the Sentinel’s interceptor missiles themselves. Kissinger noted that atmospheric detonation by a Spartan missile would more than likely “black out” the critical U.S. target acquisition radars, meaning that additional intercepts would be impossible. Thus, the modified Sentinel system would be nullifying its utility as soon as it was employed. Likewise (especially where ABM was employed to protect ICBM bases), an exploding Spartan or Sprint missile could knock out Minuteman and Titan missiles being launched in retaliation for any Soviet attack. This could not be compensated with anything less than a costly coordination system or restrictive operational procedures.

US Sprint missile being test launched

The ABM system was designed to operate in one of three modes, with command and control being conducted locally, regionally, or nationally through automation. All three modes had major disadvantages. Ultimately, the ability of the ABM system to work depended on its ability to destroy incoming warheads. “Kill assessments” were being made relative to how “hard” a Soviet warhead was (meaning its ability to withstand a nuclear blast). This in turn impacted how close an interceptor needed to be to guarantee a kill.

Kissinger noted that if the assumptions were wrong, then the system wouldn’t work. And finally, Kissinger had to concede that the modified Sentinel ABM could easily be overwhelmed by a concentrated nuclear bombardment, especially if penetration aids were employed. In short, the system’s effectiveness against a Soviet attack was nil. Kissinger acknowledged that the U.S. nuclear retaliatory capability was not threatened by any realistic intelligence estimate that extended through the decade of the 1970s.

However, the Department of Defense utilized what was known as “greater than expected” threat analysis in determining U.S. defense requirements, and if these data were applied, then the U.S. retaliatory capability would come under risk by 1976 as the Soviets deployed an increased number of larger missiles equipped with MIRVs. For this reason, the concept of deploying an ABM capability designed to ensure a minimum of 300 Minuteman missiles survived any Soviet nuclear attack was an attractive idea, especially for the Department of Defense and the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

But focusing an ABM system on a Soviet threat ran against the initial justification of the Sentinel program, namely defending against a Chinese threat. The problem was, if the United States placed too much emphasis on the Chinese threat, then the ABM could not be factored into any meaningful arms reduction talks. Nixon, in speaking out in defense of ABM, had placed considerable emphasis on China, more than Kissinger would have preferred.

But in the end, Nixon appeared to have been swayed by Kissinger’s Soviet-centric approach, supporting a focus on Minuteman ICBM defense that reflected the fact that the Soviets had closed the gap when it came to strategic parity as well as Nixon’s desire that the gap not be widened on the other side, which required that any threat to Minuteman be reduced. ABM, in Nixon’s mind, accomplished this.

On March 14, 1969, President Nixon announced his decision concerning the future of the Sentinel ABM system. Recognizing that the system as designed required modification, Nixon directed that a new, modified ABM system, using many of the same components and designs as Sentinel, be constructed. Nixon highlighted the “unmistakable” defensive nature of the new ABM system, noting that it was designed to protect U.S. land-based retaliatory forces against a direct attack by the Soviet Union, to defend the American people against the kind of nuclear attack that Communist China was likely to be able to mount within the decade, and to protect against the possibility of accidental attacks from any source. Nixon said that the new ABM system was not designed to protect American cities from nuclear attack, noting that it was not feasible to do so, and that any effort in this direction “might look to an opponent like the prelude to an offensive strategy threatening the Soviet deterrent.”

In arguing in favor of an American ABM system, Nixon highlighted Soviet capabilities—namely that the Soviets already had a functioning ABM system that they were continuing to improve. Using the briefing provided by Kissinger back in early March, Nixon pointed out that the Soviets were also continuing to deploy large ICBMs that possessed the ability to destroy silo-based Minuteman ICBMs, as well as substantially increasing the size of their SLBM fleet. Nixon also referred to the Soviet development of a “semi-orbital nuclear weapon system” (i.e., FOBs), without detailing what such a system entailed. Nixon also highlighted an ABM’s value against any Chinese nuclear threat or an accidental nuclear missile launch from any direction. Sentinel thus was renamed Safeguard.

But Nixon’s speech, rather than putting the ABM debate to bed, only breathed new life into those who opposed any ABM deployment. The scene was set for a major showdown in Congress, where the fate of the Safeguard ABM system was linked to a Senate funding bill authorizing appropriations for fiscal year 1970 for military procurement, research and development. The total amount involved for Safeguard was more than $20 billion, but the matter being debated dealt with only the $759.1 million required for the initial deployment of the Safeguard ABM system. The Senate split 50–50 on the vote on August 7, 1969. Vice President Spiro Agnew was called in as the president of the Senate to cast the decisive 51st vote in favor of the bill.

Arms control and arms reductions were still very much on the foreign policy agenda of the Nixon administration. As his point person for America’s arms control effort, the president chose the new director of ACDA, Gerard Smith, a veteran State Department official with experience in the Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson administrations.

Gerard Smith

To get arms control back on the agenda with the Soviets, President Nixon (with Kissinger present) met with Soviet ambassador Dobrynin at the White House on October 20, 1969. The ambassador opened the meeting by presenting Nixon with a brief announcement concerning arms reduction talks. The Soviets were interested in beginning a preliminary round of discussions on November 17, 1969, and were suggesting Helsinki, Finland, as the venue.

On October 25, 1969, both Moscow and Washington announced their mutual intent to begin what were being referred to as “Strategic Arms Limitation Talks,” or SALT. On November 13, 1969, Secretary of State Rogers made a public announcement on the eve of the U.S. SALT delegation’s departure for Helsinki, in which he underscored his belief that the ultimate question the SALTs would confront was “whether societies with the advanced intellect to develop these awesome weapons of mass destruction have the combined wisdom to control and curtail them.”

The two delegations sat down on November 17, 1969, and for the next five weeks probed one another as to the seriousness with which the respective parties were pursuing the issue of arms reductions. One of the areas in which there appeared to be considerable differences of opinion lay in what constituted “strategic weapons.” The Soviets insisted on including U.S. aircraft carriers and nuclear-capable aircraft stationed in Europe because these weapons could target the Soviet homeland. On the other hand, the Soviets wanted to exclude their medium- and intermediate-range missiles, which only targeted Europe, because these weapons did not threaten America.

The Soviets were pushing for either no ABM deployment or a very low level of ABM deployment and a loose verification regime based on national technical means (a euphemism for satellite-based imagery.) The Soviets proposed a halt, or even a reversal, of ABM development, indicating that a flight test ban represented the easiest means of verification. They underscored that with zero or low ABM deployment, MIRVs became unimportant and could be banned with no significant risk. The Soviets stated that if their concerns over ABM and MIRVs were met, then they would be amenable to considering a mutual halt to the construction of offensive missiles and launchers. Although there were many areas of disagreement, the two sides were finally talking about limiting strategic arms. On December 22, 1969, the preliminary discussions on SALT were recessed, with both sides agreeing to reconvene in Vienna, Austria, in April 1970.

On April 9, 1970, Kissinger met with Dobrynin, informing the Soviet diplomat that the United States was preparing comprehensive alternative proposals for a ban on MIRVs and arms reductions. However, Kissinger noted that if the Soviets were interested in a more limited agreement, then the United States might consider that as well. What Kissinger didn’t tell Dobrynin was that there were two conditions to these proposals, both of which were designed to make the Soviets balk.

The first was a requirement for on-site inspection, insisted on by the Pentagon, and the second was a loophole permitting the production of MIRVs. The Soviet Union would never approve any intrusive on-site inspection regime, and a clause permitting the manufacture of MIRVs, but not their testing, meant the United States would lock itself into a strategic advantage because the Soviets had yet to conduct MIRV testing.

The Vienna round of talks began on April 16, 1970. Early on in these talks, when Gerard Smith started reading the U.S. proposal, the Soviets took extensive notes. However, as soon as Smith got to the provision concerning on-site inspection, his Soviet counterpart put down his pen. “We had been hoping you would make a serious MIRV proposal,” he said once Smith had finished. No sooner had they begun than the Vienna talks were stalled.

Over the course of the next weeks, the Soviets countered with a proposal of their own that permitted MIRV testing but prohibited manufacture and deployment of the systems. This proposal was, perhaps intentionally, just as absurd as the American proposal, and it too was rejected. Recognizing that time was running out on any possibility of containing the MIRV problem, Smith wrote back to Washington, proposing an outright MIRV ban; Kissinger rejected this initiative.

When it came to defining the limits for each side in terms of strategic weapons, Smith came up with “Vienna Option,” proposing limits of 1,900 launchers on each side, 1,710 in missile launchers, and 250 in modern heavy missiles (i.e., the Soviet SS-9, a major concern for the MIRV-sensitive United States). This was passed back to Kissinger for review.

The Soviets also accepted a U.S. proposal limiting ABMs to one site protecting each nation’s capital. This decision guaranteed an expensive and dangerous MIRV-based arms race between the United States and Soviet Union because it locked in the numbers of missiles but with no limit on the number of warheads.

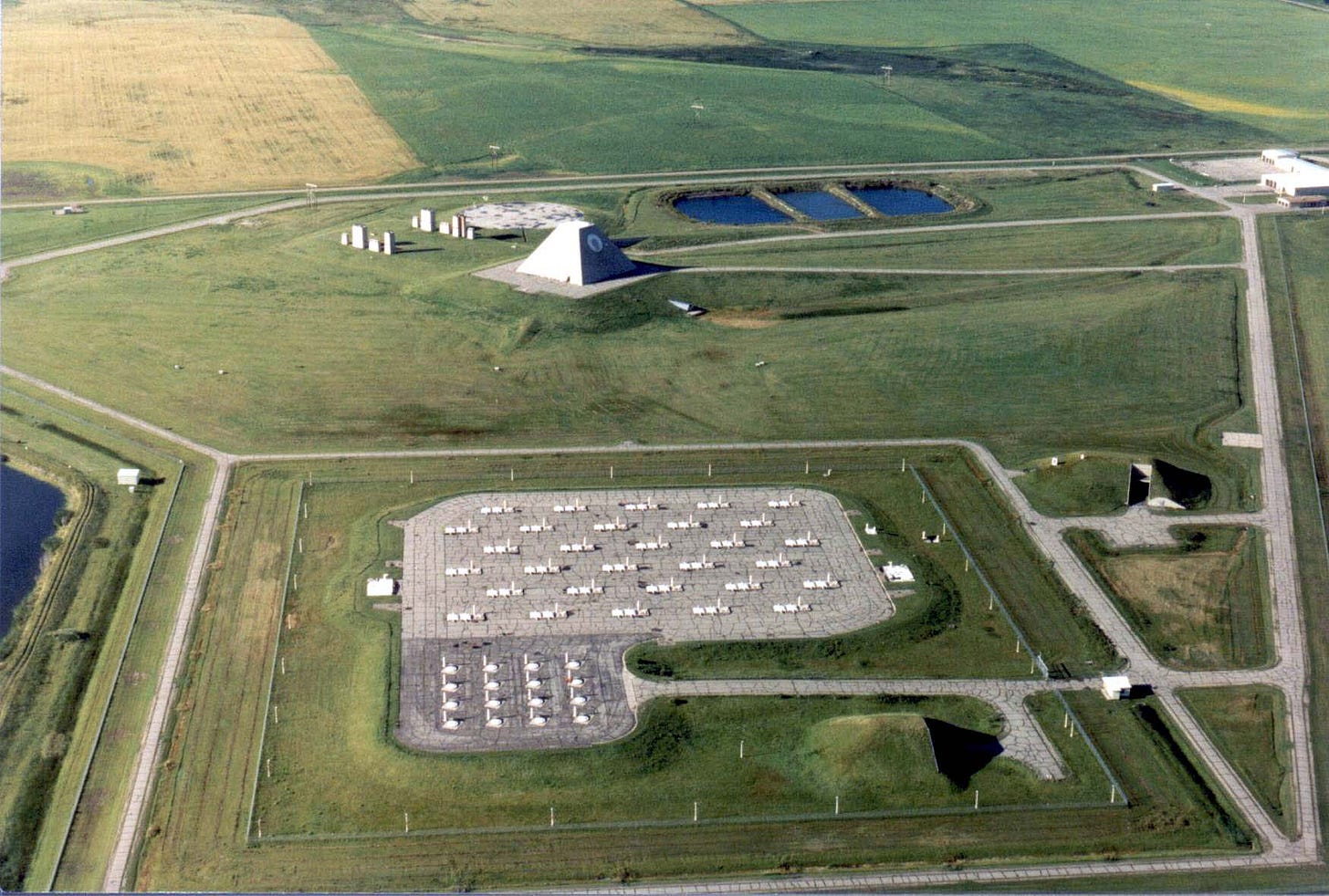

It also created a huge domestic problem for Kissinger. The Senate had voted 51–50 to approve the deployment of Safeguard, a two-site Air Force Base in North Dakota and was scheduled to begin in June 1970 at Malstrom Air Force Base, Montana. Many prominent senators from both parties had thrown their support behind Safeguard, and now it looked as if Kissinger and Nixon were negotiating the ABM system away.

Setting the stage for a confrontation with Congress, Nixon’s promise in the summer of 1969 to conduct an annual review of the ABM program created a second opportunity for congressional opponents of Safeguard to try to kill the system. In early March 1970, while Gerard Smith was formulating a U.S. SALT negotiating position, Defense Secretary Laird had gone to Congress to request funding for a “Modified Phase 2” Safeguard system.

This system comprised a third Safeguard site to be constructed at Whiteman Air Force Base in Montana, with additional missiles for the first two sites, and the appropriation of land for five more Safeguard bases, for a total budget increase of $1.5 billion on top of the $759 million Congress appropriated in 1969. As envisioned by Laird, the planned Safeguard system would comprise fourteen sites. Laird argued before Congress that the Soviets “are continuing the rapid deployment of major strategic offensive-weapons systems at a rate that could, by the mid-1970s, place us in a second-rate strategic position with regard to the future security of the free world.” Despite continued opposition in Congress, the funding request was passed.

MIRV warheads for the Minuteman III ICBM

The strategic balance between the United States and the Soviet Union appeared to have reached parity. By June 1970, the Soviets had deployed some 1,300 ICBMs and 270 SLBMs. The American number had remained unchanged, at 1,054 and 646, respectively. But the United States deployed its first MIRV-equipped Minuteman III in June 1970, and Poseidon MIRVs were due to be in place in January 1971. Thus, by the end of 1972, though the number of strategic missiles would be roughly 2,000 on each side, the United States would have 4,000 deliverable warheads, double that of the Soviets. As feared by many opponents of the MIRV, the Soviets had no choice but to push for their own MIRV capability and thus had no motive to freeze offensive weapons.

Kissinger’s allowing ABM to be de-linked from force limitations severely damaged the U.S. negotiating effort during this phase of the SALT talks. He therefore sought a U.S.-Soviet summit, preferably in the fall of 1970, in time to influence congressional elections. Nixon broached the idea to Kissinger, and on April 7, 1970, Kissinger met with Ambassador Dobrynin and raised the idea of a summit. Dobrynin agreed that the fall was the ideal time for such a summit, in time for the United Nations’ twenty-fifth anniversary celebration. Kissinger emphasized that such a summit should be linked to the SALT discussions.

A major issue facing any potential summit was the problems the Soviets were having in the course of their 24th Party Conference. For the first time in their history, the Soviets were unable to come up with a five year plan, a reflection of the severe economic stress they were facing. Much of this stress was caused by the extreme burden placed on the Soviet economy by the ongoing arms buildup.

The Brezhnev-Kosygin struggle for power was likewise coming to a head. Having heard nothing back by June 1970, Nixon had Kissinger make another push for a summit. The Soviets responded, first by trying to link any such summit with a comprehensive Middle East peace plan.

Nixon rejected this.

The second Soviet response was to offer an early agreement on ABM systems, to be finalized at a summit, in exchange for a joint U.S.-Soviet agreement on a cooperative response to any attack on one party by a third party. This proposal was raised in Vienna to Gerard Smith, who forwarded it to Kissinger in July. Again, this proposal was rejected.

Void of any potential of a radical departure from the ongoing SALT negotiations that a U.S.-Soviet summit would offer, Kissinger circulated new negotiating instructions to Smith and his delegation, which represented, in fact, an official embrace of Smith’s Vienna Option. In it, Kissinger stated that the limitations goals for the United States included capping the aggregate number of ICBMs, SLBMs, and strategic bombers at 1,900 for each side, with an added condition that heavy missiles produced after 1965 could not number more than 250. Within the agreed total, the aggregate number of ICBMs and SLBMs should be limited to 1,710. After any transition period to allow for both sides to reach the agreed-upon arms cap, the United States would then propose a ban on mobile ICBMs and new missile silo construction. The United States’ definition of “strategic weapons” would remain unchanged from that put forward in earlier instructions.

Kissinger also put forward two negotiating positions concerning ABM, the first limiting deployment to a single site protecting a national capital (the National Command Authority, or NCA, option), the second a “zero” option banning all ABMs. The negotiating instructions concluded by noting that “the United States continues to support a comprehensive agreement, along the lines of either of the approaches already outlined and that we will seek to have an initial agreement followed by further agreements, including if possible controls on multiple independently targeted re-entry vehicles.”

The Soviets surprised the Americans by immediately agreeing to the NCA option for ABM deployment. Kissinger had agreed to put this on the table because he assumed the Soviets would reject it and ask for a more robust ABM defense. However, the remainder of the negotiating points became deadlocked. By insisting on the old interpretation of strategic weapons, the United States failed to address the Soviet concerns of what they termed “forward-based systems,” or FBS—namely, U.S. aircraft carriers and European-based tactical aircraft that could strike the Soviet Union. The Vienna round of SALT discussions was scheduled to come to an end on August 14, 1970, and the late release of the new negotiating instructions made any hope of doing anything other than simply transmitting the new U.S. position fruitless. Progress would have to wait until the delegations reconvened in Helsinki on November 2, 1970.

The delay in getting a U.S.-Soviet summit underway, brought on largely by the Kissinger-driven insistence on policy linkage between such issues as Vietnam and SALT, created opportunities for others to take center stage in influencing East-West relations. On August 12, 1970, West Germany’s newly elected leader, Willy Brandt, traveled to Moscow, where he signed a West German-Soviet treaty that recognized both East Germany and the special status of Berlin. Responding to his critics, Brandt noted that “with this treaty nothing has been lost that had not long since been gambled away.”