Sometimes Humanity Gets it Right

ooo

Sometimes Humanity Gets it Right

Disarmament in the time of Perestroika spotlights the pivotal contributions of U.S.-Soviet inspectors in helping to complete the 1988 INF treaty. The US and Russia could learn from its lessons.

Jan 31, 2026

Inspectors with U.S. flag outside Votkinsk Factory, December 1988

(Note: This article was originally published in Consortium News on August 15, 2022—three years after President Trump withdrew the United States from the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty. In a week’s time, the United States, again under President Trump’s leadership, will allow the last remaining arms control treaty, New START, to expire, putting the US and Russia on the path of a new nuclear arms race, with all the dangers and expenses that entails. I will be writing extensively on this topic in the days ahead. But I thought that the perfect starting point for this journalistic journey would be the treaty that started it all—the INF treaty. And since I don’t believe in re-inventing the wheel, I have opted to re-publish this article, since I believe it covers the topic of the importance of arms control quite well.)

When it comes to U.S.-Russian arms control, sometimes history should repeat itself

President Joe Biden recently called for Russia to resume arms control negotiations aimed at keeping the existing New START treaty, scheduled to expire in 2026, viable.

Russia responded by suspending all inspection activity related to New START, declaring that the United States was seeking unilateral advantage by denying Russia access to inspection sites in the US, while demanding that Russia permit American inspectors access to sites in Russia.

Arms control, once the cornerstone of U.S.-Russian relations, appears to be on life support, and with it the future of international peace and security. My new book, Disarmament in the time of Perestroika: Arms Control and the End of the Soviet Union, provides an historical precedent which gives hope that the current negative trend in relations between the U.S. and Russia could be reversed if both parties were willing and able to recapture the spirit of the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, which entered into force on July 1, 1988.

The history of the INF Treaties first two years of implementation is the topic of The Life of Reason: Reason in Common Sense by the American philosopher, George Santayana. In it, he notes that “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” The clear implication behind this phrase (focusing on the use of the term condemned) is that history is a collection of human error which, given human nature, will inevitably repeat itself unless a concerted effort is made to study the past and learn from the mistakes made to prevent their reoccurrence.

History, however, is much more than a simple recantation of past failure. Sometimes humanity gets it right. Sometimes the study of history is invaluable because it can provide a template of success that would be useful in navigating the troubled waters of human existence.

The story of the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty is one such instance.

The relations between Washington, D.C., and Moscow were at an all-time low. After a long Cold War, there was a brief period of détente, a genuine warming of relations where peaceful coexistence seemed to take priority over armed confrontation.

But then a series of geopolitical crisis, marked by Moscow’s military aggression against its neighbors, breathed life into Russophobia which had lain dormant. The Russian people, its culture, language and history were collectively denigrated, subordinated to a cartoon-like characterization of their leadership, which was presented to the American people as autocratic and cruel, a literal “evil empire.”

The U.S. soon became engaged in a proxy war with Moscow, sending arms and ammunition to help those whose lands had been invaded by the Russians fight back. The goal of the U.S. wasn’t to defeat Moscow, but rather weaken it by inflicting unacceptably high casualties and costs for their military aggression against a neighboring nation.

Economic sanctions were imposed by the U.S. and its allies that were designed to limit Moscow’s connectivity with the West with the goal of denying it a revenue stream while starving it of critical Western-sourced technology.

Arms control agreements, decades in the making, were shunted aside, with the result being that Washington, D.C., and Moscow found themselves engaged in a new arms race which threatened all of humanity with nuclear annihilation.

Neither side trusted the other, and the possibility of a realistic diplomatic offramp from the highway to hell that had been constructed by the U.S. and Russia seemed improbable, if not impossible.

Sound familiar? A knowledgeable observer of international affairs could reasonably assert that the scenario depicted above was a spot-on recitation of how things are going now between the United States and Russia.

However, the passage describes U.S.-Soviet relations between 1979 and 1986. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 set in motion a decade-long proxy war where the U.S. supplied Afghan insurgents with modern weaponry, including advanced Stinger surface-to-air missiles, that was used to kill hundreds, if not thousands, of Soviet troops. U.S. sanctions targeted Soviet energy exports and the U.S. walked away from the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT) in protest over the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

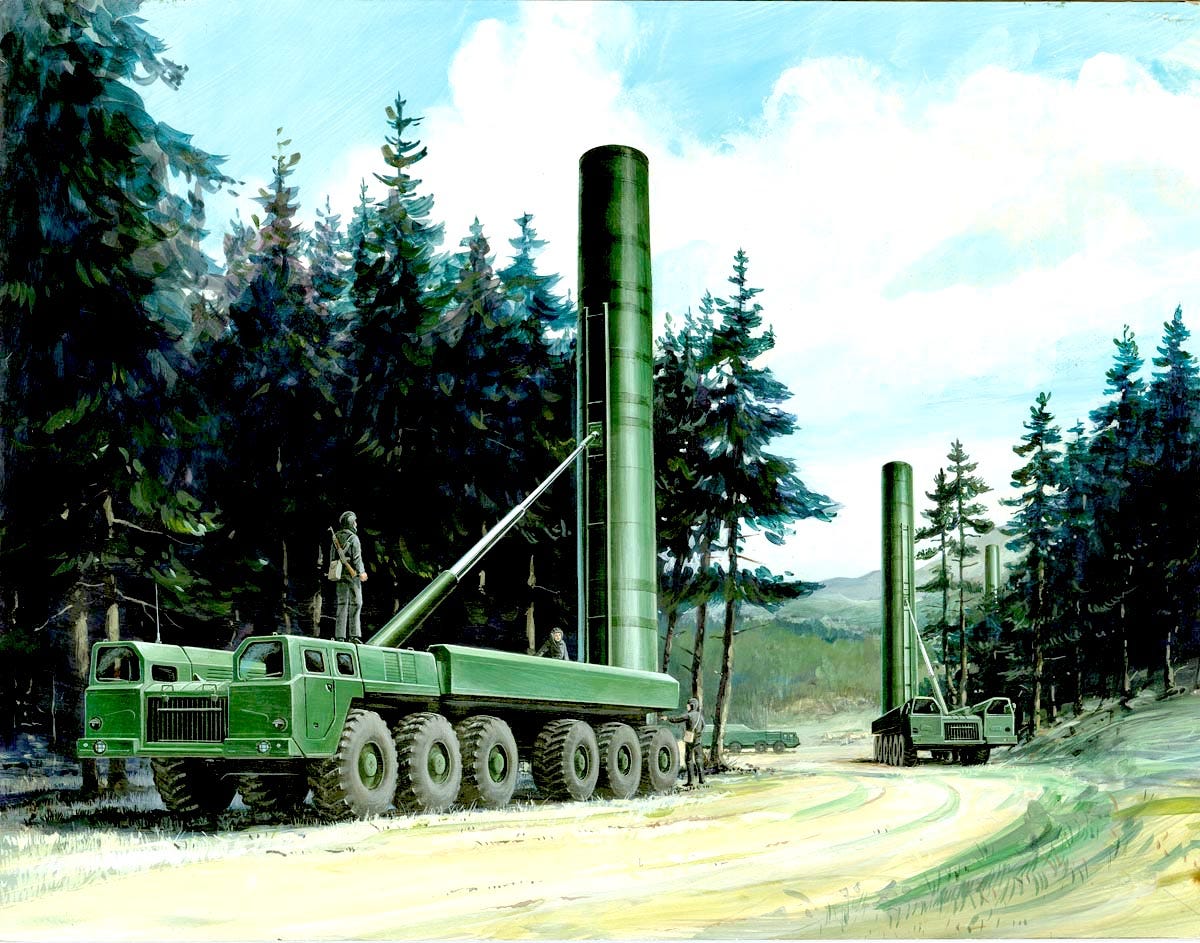

Meanwhile, the Soviet Union was in the process of deploying a new mobile ballistic missile, the SS-20, which threatened the balance of power in Europe. The U.S. responded by deploying to Europe advanced ground-launched cruise missiles and Pershing II ballistic missiles. These weapons put Europe and, by extension the world, on the edge of the abyss, where any mistake or misunderstanding could trigger the launch of nuclear weapons that would end all of humanity.

Illustration of Soviet SS-20 launchers

This was not simply idle conjecture. The experiences of Able Archer ’83, a NATO military exercise in the fall of 1983, serves as testament to the danger. Designed as a command post exercise to test the various processes associated with the use of NATO’s nuclear weapons, Able Archer ’83 was instead construed by the Soviets as representing preparations for an actual preemptive nuclear attack by NATO.

The level of mistrust between the U.S. and Soviet Union at the time was immense, as were the consequences. While Americans today wrestle with the issue of Britnney Greiner and her arrest and prosecution by Russia on drug charges, in the 1980s the U.S. had to deal with the Soviet downing of a Korean airliner, KAL 007, in which 62 Americans, including a U.S. congressman, were killed, and the shooting death of an active duty Army officer, Major Arthur Nicholson, by a Soviet sentry outside a Soviet military facility in East Germany.

Today, the deterioration of U.S.-Russian relations is a matter of personal inconvenience. In the 1980s, it was literally a matter of life and death.

If one were to turn on the television today, and/or read the mainstream newspapers and journals, for the purpose of trying to ascertain the current state of affairs between the U.S. and Russia, the inescapable conclusion mandated by any logical assessment of the available data would be that they are at the lowest level in decades and that there is no discernible path forward.

Arms control has been a constant go-to diplomatic move for both parties, the final bastion of reason around which a red line could be drawn that said “no further” regarding the deterioration of relations, if for no other reason than neither side wanted to release the nuclear genie that had been bottled up back in 1987, when the INF treaty was signed. With the future of the last remaining arms control treaty — New START — now in doubt, even this limit no longer appears sacred.

Which brings us back to George Santayana.

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

History is a fickle thing. Students of history either operate at the mercy of those individuals — historians — who have taken it upon themselves to assemble data in a manner that best represents a factual narrative of a given place and time or undertake to do the fundamental research necessary to produce useful and meaningful works of history, in which case their findings are governed by the availability of primary source material sufficient to the task.

U.S. President Ronald Reagan and Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev signing the INF Treaty in the White House in 1987

The INF Treaty, and the history of its creation and initial implementation, is a case where historians are not in danger of forgetting the lessons offered by that experience, but rather denied the opportunity to learn these lessons to begin with because they have been unable to gain access to the source material necessary to capture the totality of that experience.

As such, any template of success constructed from the available record would be incomplete, and as such unable to effectively reproduce the success of the events involved.

There have been histories written about the INF Treaty, both in terms of its negotiation (David T. Jones’ outstanding The Reagan-Gorbachev Arms Control Breakthrough stands out) and implementation (Joseph P. Harahan’s On Site Inspections under the INF Treaty is unique in this regard).

While competent histories, the authors were limited by the very treaty that they were writing about (the inspection protocol of the INF Treaty, Section VI, paragraph 2, declares that “Inspectors shall not disclose information received during inspections except with the express permission of the inspecting Party. They shall remain bound by this obligation after their assignment as inspectors has ended.”)

The result is that anyone seeking to “recapture” the experience of the formative phase of the INF treaty would be limited to dry, overly technical texts which missed completely the intimate details that define a place in time, and the people who populated it.

As one of the original team of military personnel assembled by the U.S. Department of Defense to carry out inspections inside the Soviet Union pursuant to the INF Treaty, I helped write the book about on-site inspections.

As a member of the advance party of inspectors dispatched to the Soviet Union, back in June 1988 (two weeks prior to the treaty entering into force on July 1), I was one of the first inspectors to turn the “book” of on-site inspections into reality.

Prior to the INF Treaty, both the Soviet Union and the United States were loath to allow personnel from the other side access to sensitive locations deemed relevant to various arms control agreements, and as such critical to verification activities necessary to ensure compliance with whatever restrictions or conditions had been imposed by any treaty.

This meant that verification was at the mercy of “national technical means” (NTM, or satellites), which were limited by the state of technology at the time and, as such, unable to overcome the deep concern that existed in both Moscow and Washington that the other side would take advantage of any physical presence on the soil of the other to carry out espionage operations.

The level of compliance verification mandated by the INF Treaty, however, precluded the exclusive use of NTM. Given the importance that both the U.S. and Soviet Union attached to the INF Treaty, it was agreed that on-site inspections would be incorporated into the treaty, not as a supplement to NTM, but rather as the principal means of compliance verification.

A Soviet inspector examines a BGM-109G Gryphon ground-launched cruise missile in 1988 prior to its destruction

There were several kinds of inspections envisioned under the INF Treaty.

-Baseline inspections were conducted for each location listed in the treaty text as an inspectable site and were intended to establish a baseline of data which would be used for future verification purposes.

-Elimination inspections oversaw the disposition of missiles and missile support equipment scheduled for destruction under the treaty.

-Closeout inspections were conducted when a site had been deemed to have been “cleansed” of all treaty-limited items and/or activities.

-Short notice inspections were conducted to either verify that a site, once “closed out,” remained in compliance, or to investigate any potential violation.

These four inspection types represented the core inspection activity conducted under the INF Treaty and, indeed, were originally envisioned as the only inspection activities that would be carried out. However, in November 1987 — only weeks away from the treaty signing ceremony scheduled to take place on Dec. 8 in Washington, D.C., — the Soviets informed their American counterparts that the first stage of the SS-25 intercontinental ballistic missile, which was not affected by the treaty, was virtually identical to the SS-20 intermediate-range ballistic missile, which was prohibited under the treaty.

In the early INF negotiations, the Soviets had argued for their need to retain a limited number of SS-20 missiles which would be deployed in Asia, away from the European theater of operations.

The U.S., which was arguing against any retention of SS-20 missiles, came up with a notional inspection scheme — perimeter portal monitoring, or PPM — which would “capture” a Soviet missile production facility — in this case, the Votkinsk Missile Final Assembly Plant, located some 750 miles east of Moscow in the foothills of the Ural Mountains — in order to monitor production to ensure that the Soviets did not produce more missiles than permitted under a potential INF Treaty.

The PPM scheme was considered so intrusive by the Soviets that they quickly agreed to the “zero” option to avoid having to implement it.

Now, confronted with the Soviet information about the SS-25/SS-20 first stage similarity, U.S. and Soviet negotiators were faced with either delaying or cancelling the treaty altogether, or quickly agreeing to an inspection scheme that could be incorporated into the treaty text that would allow for verification that any SS-25 missiles produced by the Soviets were not prohibited SS-20 missiles. The PPM inspection scheme, which was never intended to be implemented, was chosen as the solution.

Unlike the other four categories of inspections under the INF Treaty, for which detailed procedures had been agreed upon and spelled out in detail in the inspection protocols of the treaty text, PPM (which incorporated untested verification technologies such as infrared measuring and radiographic imaging) had no such agreement.

It was decided that the specifics regarding PPM installation and operations would be spelled out in a separate memorandum of agreement to be negotiated by the US and Soviet sides after the INF Treaty was signed, and ideally before the treaty went into force (scheduled for July 1, 1988.)

As fate would have it, the technical details associated with PPM were too complex to be resolved in such a short period of time, meaning that when the first U.S. inspectors arrived in Votkinsk to begin the installation and operation of the PPM facility, they had no agreed upon procedures to govern their work.

Treaty negotiators had passed the buck, leaving it up to the U.S. inspectors and their Soviet counterparts at the Votkinsk factory to develop these procedures in a collaborative fashion. This created a set of circumstances unique in the history of arms control.

On one side an inspecting party was under pressure to install and operate a technically complex monitoring system of unprecedented intrusiveness. On the other, an inspected party was tasked with producing weapons deemed critical to their national security and protecting information and data related to this production from foreign intelligence services. Somehow, they had to come together to ensure the common objective of treaty compliance.

In one fell swoop, the issue of PPM transitioned from a technical problem into a human problem. When U.S. arms control experts agreed to introduce the “human factor” into compliance verification, they had done so on the conditions that the humans would be operating from a very specific playbook — the inspection protocols — which allowed for virtually zero deviation from agreed-upon technical parameters.

There was to be no “free play” where inspectors were given latitude to adapt to unforeseen circumstances. From the standpoint of the arms control experts, the unpredictable nature of the “human factor” was in and of itself a threat to compliance verification, representing as it did a deviation from the strict norms and standards the believed were required for that mission.

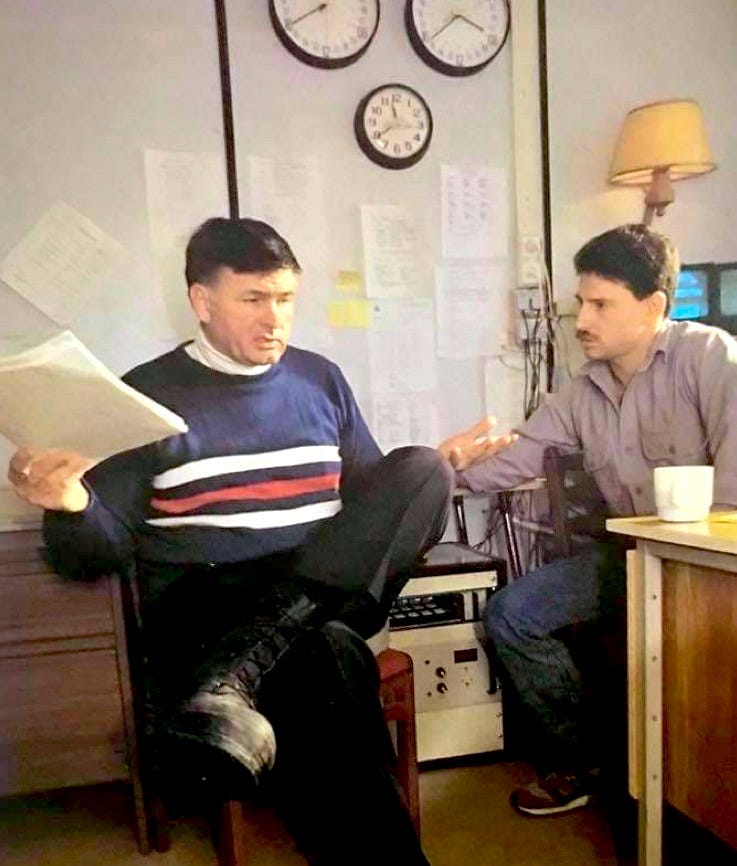

Inspectors in their office, July 1988

PPM, however, was all about the “human factor,” which was to prove to be critical for the success of the treaty. The “human factor” was captured in the daily logs maintained by the inspectors, in the regular reports from the inspectors to headquarters, and in the written correspondence between the inspectors and their Soviet counterparts.

These reports provide a day-by-day, and in some cases hour-by-hour, account of how the U.S. and Soviet inspectors labored together to accomplish the impossible — to successfully install and operate a PPM facility while overcoming unimaginable logistical and political obstacles raised by both parties.

The story of how this collaboration unfolded, however, could not be told in full without the aforementioned documents and reports. While the information contained in these documents was unclassified, it remained protected from publication by the treaty provisions prohibiting unauthorized disclosure.

When I was an inspector in Votkinsk, I was approached by Marine Corps Colonel George Connell, who served as one of two site commanders of the Votkinsk Portal Monitoring Facility (the other was an Army colonel, Doug Englund). I had, by this time, published two scholarly articles in highly regarded academic journals, and Colonel Connell wanted me to turn my research and writing skills to capturing the history of the Marine Corps involvement in the Votkinsk inspection experience.

I began collecting the various reports produced by the inspection experience, creating an archive that would serve as the basis for my writing. I eventually produced a draft article, which was submitted to the Marine Corps Gazette for consideration. The editors, however, deemed the topic too esoteric for the general Marine Corps audience, and turned the manuscript down.

Colonel Connell told me not to fret. “This is a story that must be told some day, and you are uniquely positioned to tell it.” Thus motivated, I continued to assemble my archive of reports, hoping that someday I would be able to write the story of the Votkinsk inspection experience.

In the fall of 1991, I published an article, “Soviet Defense Conversion: The Votkinsk Machine Building Plant,” in the journal Problems of Communism.

While much of the article drew upon open-source materials, I did make use of some of my archived inspection reports. The Department of Defense, when reviewing the manuscript as part of their prepublication security procedures, objected to my use of this information, as it represented a potential violation of the treaty language prohibiting the unauthorized disclosure of information received during inspections.

While I was able to reach an accommodation regarding the article, the experience had a chilling effect on any future writing projects I had envisioned regarding Votkinsk and my archive of inspection reports.

Indeed, I had begun work on a book-length project tentatively entitled Perestroika in the Hinterlands, that I felt compelled to terminate because of the inability to fully incorporate the information I had collected during my time as an inspector.

Then, in August 2019, President Donald Trump precipitously withdrew the U.S. from the INF Treaty. His action was followed a similar move on the part of the Russian Federation. Overnight, the prohibition regarding the use of inspection-derived information evaporated, since the treaty that had imposed it no longer existed.

For the next two and a half years I devoted myself to turning the Votkinsk archive into a book that captured the spirit of the “human factor” that made the Votkinsk experience what it was in the early years — one of the greatest success stories ever.

That book is Disarmament in the Time of Perestroika: Arms Control and the End of the Soviet Union, which was published this summer by Clarity Press.

Unfortunately, I had to write this book without the mentorship and guidance of George Connell, who had passed in 2015. I was likewise denied the wisdom and insight of Doug Englund, who together with George Connell made the Votkinsk experience the success that it was. Doug passed in 2017.

The presence of these two men was felt in every page of every document I read and every photograph I examined while researching the book. I dedicated the book in the memory of both men, “two ardent Cold Warriors transformed into Pioneers of Peace.”

Doug Englund and John Sartorious

While the book is intended to be a definitive history of the first two years of the Votkinsk inspection experience, there is no escaping the fact that it is also an autobiographical work, hence the notation on the cover, “A Personal Journal.”

Much of the story of the work of the inspectors, and their interactions with their Soviet counterparts, is told through my eyes, and I have cast myself as sort of an “everyman,” a justifiable role given that most of what I impart in the book, especially the emotional and physical realities encountered, being very much a shared experience.

When I first arrived outside the Votkinsk Factory in June 1988, I was confronted by an empty field except for a single road and rail line that led to the imposing main gate of the walled-off facility.

A year later, that field had been transformed into a self-contained housing complex comprised of four two-story dormitory-like structures, a data-collection center which served as the operational hub of the inspections, a temperature-controlled structure used to carry out visual inspections of missiles leaving the factory, a warehouse where the spare parts and equipment needed by the inspectors to operate and maintain the monitoring facility were stored and a giant concrete-and-metal structure intended to house a massive X-Ray device, known as CargoScan, which the inspectors would use to make sure SS-20 missiles weren’t shipped out of the factory disguised as SS-25s.

The story about how this transformation occurred is the heart of the book. To construct this portal monitoring facility, inspectors and inspected alike had to come together in what can only be described as a labor of love, overcoming all the challenges Mother Nature could impose in terms of sweltering, mosquito-and-tick-infested summers, the oppressive muck and mire produced by the spring and fall mud seasons and the mind-numbing cold of the Russian winter to build a complex according to a treaty-mandated timeline which was unforgiving in its exactitude.

Cargoscan

The “human factor” made this all possible, with U.S. military officers and civilian contractors working alongside Soviet factory workers in common cause. I tried my best to do these men and women justice, breathing life into their names and deeds so that they become more than just words on a page, but rather an extension of the readers themselves, who hopefully feel like they have been transported back in time to Votkinsk circa 1988-1990.

The inspection experience did not occur in a vacuum, but rather was part and parcel of one of the more turbulent periods in the history of the Soviet Union, namely the implementation of the policy of perestroika by Mikhail Gorbachev, involving as it did the complete restructuring of the Soviet political and economic system.

When I arrived in Votkinsk in June 1988, Gorbachev had convened the 19th All-Party Union Conference for the purpose of injecting the concepts of perestroika into the mainstream of Soviet society. The conference set off a revolution of sorts which resonated throughout the Soviet Union, and especially so in a town like Votkinsk, where Votkinsk factory dominated every aspect of the day-to-day lives of its citizens.

The inspectors were direct observers of this revolution, both through their extensive contact with the citizens of Votkinsk (we lived among them), and by reading the local Soviet press.

Under the new regime of glasnost, or openness, the local Communist Party newspaper, Leninski Put’ (“Lenin’s Path”) was transformed from a simple mouthpiece of authority into a first-rate journalistic outlet, with its editorial staff and stable of capable writers performing quality investigatory reporting that would put many of their American counterparts to shame. Through their work, the U.S. inspectors were able to peer inside the humanity of Votkinsk, getting a detailed glimpse into the good, the bad and the ugly reality of Soviet life in transition.

I was able to capture these journalistic accomplishments in my Votkinsk archive and drew extensively on the information and insights contained in the articles published in Leninski Put’ and other local and regional newspapers and magazines to capture the day-to-day reality of life in Votkinsk during the time of perestroika.

In doing so, I was able to weave together the disarmament aspects of the inspection experience and the human reality of perestroika into a seamless narrative that captures the way each impacted and influenced the other.

New Year’s tree, Votkinsk, December 1988

This is the crux of the title of the book, Disarmament in the time of Perestroika. In many ways, the INF Treaty was a byproduct of perestroika, the living manifestation of the changes being sought by Gorbachev in pursuing that policy. And, in the end, when the challenges of implementing perestroika proved to be too much for the Soviet system to take, the disarmament processes triggered by the INF Treaty set in motion the events which led to the collapse of the Soviet Union (hence the second part of the title of the book, Arms Control and the End of the Soviet Union.)

The INF Treaty survived the collapse of the Soviet Union, a testament to the work of those on both sides to build something of lasting consequence. After the treaty-mandated 13-year inspection period ended, on June 1, 2001, Votkinsk transitioned away from its INF responsibilities, and instead functioned solely in its role as a Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) portal monitoring facility, a role it formally assumed in 1994.

This longevity, however, was not a given at the start of the INF experience in Votkinsk. Cold War paranoia infected the minds of many in Washington, D.C., who were fundamentally opposed to any meaningful disarmament between the U.S. and Soviet Union.

Led by Sen. Jesse Helms, this group sought to trip up the INF Treaty at every turn, accusing the U.S. inspectors of incompetence and their Soviet counterparts of noncompliance in building their case that the United States should terminate the treaty on the grounds that it posed a threat to national security.

At the heart of this controversy was the CargoScan X-Ray system. It was supposed to be installed and operating by the end of December 1988, but the summer of 1989 saw the system still undergoing testing in the United States.

Construction of the concrete and steel structure that would eventually house it was impacted by this delay, and by the reality that, given the rushed nature of turning the theory of PPM inspections into reality, the U.S. lacked the kind of detailed construction blueprints and design drawings needed to assuage Soviet concerns that the United States might be installing something that permitted data to be collected above and beyond that required by the treaty.

The political pressure placed on the inspectors to get CargoScan up and running clashed with the Soviet demands that CargoScan operate only within the parameters mandated under the INF Treaty, leading to a major crisis in March 1990 which threatened to bring down the INF Treaty.

The story about how this crisis came to pass, and how the inspectors and their Soviet counterparts were able to reach an agreement about the operation of CargoScan, thereby saving the treaty and, by extension, nuclear disarmament between the US and Soviet Union, is told in vivid detail, both in terms of the technical and political issues involved, and the “human factor” behind every decision and action taken.

Heroes emerge on both sides, people like George Connell and Doug England, the site commanders upon whose shoulders the burden of command rested.

Others, like Barrett Haver and Chuck Meyers, served as the foundation upon which Connell and Englund built their inspection team. What these men had in common, besides their undying commitment to seeing the task of installing and operating the Votkinsk portal monitoring facility, was that they were supposed to be there.

All four men were trained as Soviet foreign area officers, which meant that they possessed formal language training, advanced degrees in Russian area studies and specialized cultural immersion training so that they could fulfil tasks specific to the Soviet threat.

When the Department of Defense sought to build the inspection team that would implement the INF Treaty, they almost exclusively drew upon the available cadre of Soviet foreign area officers to fill the required billets, men who by the nature of the experience required to serve as a FAO wore the rank of major, lieutenant colonel and colonel.

But the unique nature of the Votkinsk experience, emanating as it did from unforeseen circumstances, meant that additional human resources were required which did not conform to the stringent FAO-like parameters envisioned by the Department of Defense.

A cadre of junior officers — mere lieutenants at the time they joined the inspection team —ended up playing an oversized role in the inspection process. Included in this group was John Sartorius, an Army officer who formerly served as an enlisted Russian linguist tasked with monitoring Soviet communications. John was a walking encyclopedia of treaty-related knowledge and was the go-to person when it came to crafting the critical compromise that brought an end to the crisis surrounding the installation and operation of CargoScan.

John literally saved the treaty.

Another junior officer whose accomplishments left their mark was Stu O’Neal. Like John, Stu had previously served as an enlisted man in the U.S. Army, where he was assigned to a top-secret Special Forces unit stationed in Berlin known as Detachment A. While in Berlin, Stu and others from Detachment A were tasked with providing a team to help with the rescue of American hostages in Iran. When a helicopter collided with a transport plane on the ground in Iran, setting them both on fire and trapping several men inside, Stu ran into the burning aircraft to rescue the trapped men.

In Votkinsk Stu was not called upon to perform feats of physical heroics, but rather serve at the front line of the inspector experience. Stu was the first inspector to conduct an external inspection of a Soviet SS-25 missile in its launch cannister, and the first inspector to conduct a visual inspection of the interior of the cannister once opened. He was the duty officer during the height of the CargoScan crisis and was the first duty officer to carry out an imaging inspection of an SS-25 missile using CargoScan. These “firsts” did not happen by accident but were reflective of the adage that true leaders lead from the front.

Stu was a true leader.

The “human factor” included the civilian contractors, without whom nothing would have been accomplished. John Sartorius’ encyclopedic mind was enhanced by the practical engineering talents of men like Sam Israelit and Jim Lusher. And if Barret Haver and Chuck Meyers were the foundation upon which the Votkinsk portal monitoring facility was built, then the brick and mortar was comprised of civilian contractors like Anne Mortenson, Zoi Haloulakos and Mary Jordan, who provided invaluable linguistic and operational support, and Hal Longley, Mark Romanchuk, and Joe O’Hare, who labored in the heat, mud, snow, and ice to turn disarmament theory into reality.

The Votkinsk experience was not just about work, however, but about life. None lived life in Votkinsk with the gusto displayed by Justin Lifflander. Justin was joined by Jim Stewart and Thom Moore in forming a counterculture movement centered on a never-ending poker game which convened in an unauthorized recreation center established in the basement of one of the housing units.

Here inspectors would gather to unwind after long and trying days building and operating the portal facility. The humanity of this environment is best expressed by the music written and performed by Thom Moore, an accomplished musician and songwriter before he decided to volunteer as an inspector in Votkinsk. His song, Prayer for Love, was written in Votkinsk, in between work and poker games, and stands as a living testimony to the humanity of everyone who played a part in the Votkinsk experience.

The Americans did not work in a vacuum — everything they did was as part of a team which included their Soviet counterparts, whose work and lives the book tries to capture as well. Men like Anatoli Tomilov, the Director of Department 162, tasked with overseeing the implementation of the INF Treaty tasks at the Votkinsk factory, and his deputy, Vyacheslav Lopatin, a huge bear of a man entrusted with technical security matters.

Given the nature of their respective tasks, Tomilov and Lopatin were at the center of every controversy that emerged between the US inspectors and their Soviet hosts. Their common sense, intelligence, and desire to accomplish the mission played a major role in overcoming all challenges faced in Votkinsk.

Anatoli Chernenko, who was responsible for all construction activities at the site, moved mountains to make Votkinsk a reality, overcoming Soviet bureaucratic inertia and American incompetence to finish the gargantuan construction tasks he was assigned to accomplish through sheer force of will.

And the Soviet factory workers — men like Aleksandr Yakovlev, Vladimir Kupriyanov, Nikolai Shadrin, Aleksandr Fomin, and Yevgenii Efremov — whose lives had been previously centered around the construction of missiles designed to strike targets in America, but who were now called upon to help disarm their nation of these very same weapons, all the while knowing that as they did so, they were undermining the very economic foundation that had sustained them and their families in years past.

They did not know what the future held for them, and yet in this sea of uncertainty, they never lost faith in their mission. Their names, and the names of their comrades, deserve to be carved into the pantheon of heroes, if ever one is constructed to commemorate the INF Treaty.

People like Elvira Bykova, the editor of Leninski Put’, and Doctor Evgenii Odiyankov and the staff of the Izhevsk cardiology center, also played oversized roles in the “human factor” that defined the Votkinsk experience.

Bykova and her staff opened the eyes of the inspectors to the reality of Soviet life during the transitions brought on by perestroika, while Odiyankov played a major role in saving the life of an inspector who had suffered a heart attack.

The relationship between the inspectors and the Izhevsk cardiology center born of that experience helped define the overall relationship between U.S. inspectors and Soviet citizens in general. Perhaps more importantly, it led to a collaboration between Americans and Soviets alike to save the life of a sick 8-year-old Russian girl named Olga.

There can be no greater testimony to the worth of any undertaking than saving the life of a child.

Except, of course, if that same undertaking saves all of humanity. The world has forgotten the reality that existed in the 1980s, and just how close we all were to a nuclear apocalypse. Those who knew about the INF Treaty, and the role it played in ending this lemming-like rush to the nuclear abyss have either died off or found themselves, and their knowledge, relegated to the bin of history, never to be studied and, as a result, never to be emulated.

Santayana lamented the fate of those who failed to learn the lessons of history, noting that they would be condemned to repeat it.

In the case of the INF Treaty, those who fail to learn its invaluable lessons are instead condemned to missing the template it provides for a resolution to superpower conflict.

I believe my book, Disarmament in the time of Perestroika, is a unique work of history. Not only does it enlighten the reader about a critical time in world history, but — perhaps more importantly — it provides hope for a possible resolution to the problems that confront the United States and Russia today.

It is the lesson of history that must be learned, not for the purpose of avoiding past mistakes, but rather for providing a blueprint for resolving seemingly insurmountable dispute today. It should be read, digested, and acted on by as many people as possible, here in the United States, in Russia, and around the world.

Who knows? Maybe someday, in the not-so-distant future, a new generation of Americans and Russians can be called upon to save the world by following in the footsteps of those who have gone before them, implementing a new round of arms control treaties capable of walking their respective nations back from the brink.

(I will be travelling to Russia in March to continue my efforts to promote arms control and better relations between the US and Russia. As an independent journalist, I am totally dependent upon the kind and generous donations of readers and supporters to underwrite the costs associated with such a journey (travel, accommodations, meals, studio rental, hiring interpreters, video production and editing, etc.) I am grateful for any support you can provide.)

oooooo

Mondays Suck

https://open.substack.com/pub/scottritter/p/mondays-suck?utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=email

ooo

Mondays Suck

Megyn Kelly graduated from the same High School as my children. They turned out to be completely different people. I am extremely proud of my daughters. Megyn Kelly? Not so much.

Jan 30, 2026

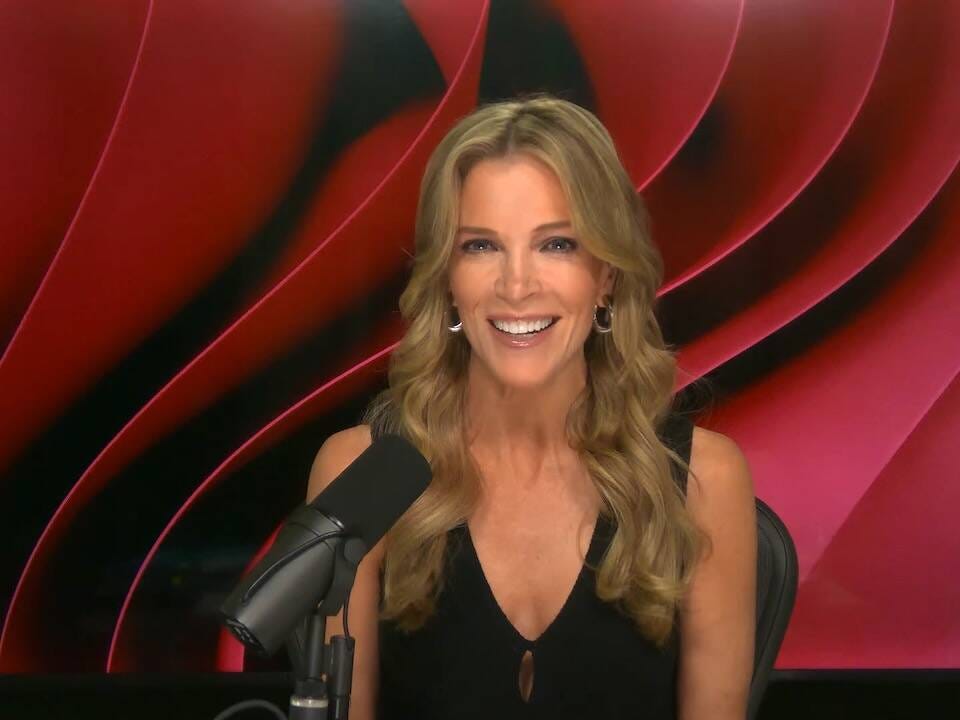

Megyn Kelly

Through the winter’s ice and cold

Down Nicollet Avenue

A city aflame fought fire and ice

‘Neath an occupier’s boots

King Trump’s private army from the DHS

Guns belted to their coats

Came to Minneapolis to enforce the law

Or so their story goes

“I know I’m supposed to feel sorry for Alex Pretti, but I don’t.”

These words came out of the mouth of an all-American woman, her fashionably long blonde hair falling down over her shoulders, her professionally made-up face staring at the camera she was speaking to.

“I don’t”, she repeated, her blue eyes flashing with outrage. “Do you know why I wasn’t shot by Border Patrol this weekend? Because I kept my ass inside and out of their operations.”

By this time, the lady with the supermodel good looks started to change her appearance. Her perfect teeth, framed by lips colored with lipstick designed to stand out, took on the characteristics of a snarl, not a smile. As she spoke, her eyes would narrow into a squint, exposing wrinkles that made the snarl a sneer. This transformation happened in just the span of a few seconds, the once beautiful woman becoming a hate-filled monster right before our very eyes.

“If I felt strongly enough about something the government was doing that I’d go out and protest, I’d do it peacefully on the sidewalk without via a whistle, via shouting, via my body, via any other way. I would make my objections known by standing there without interfering, because interfering is where you go south.”

By “going south”, the blonde lady meant being executed by masked ICE agents in the streets of Minneapolis, Minnesota.

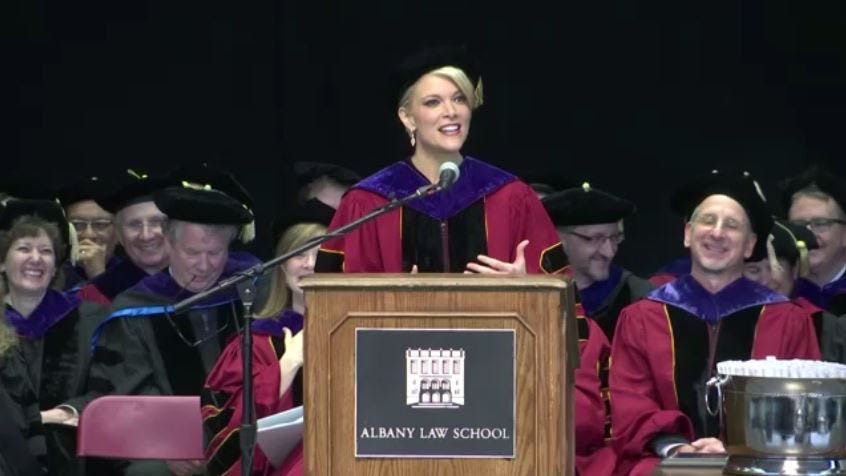

Megyn Kelly delivers the 2016 commencement address at Albany Law School

Against smoke and rubber bullets

By the dawn’s early light

Citizens stood for justice

Their voices ringing through the night

And there were bloody footprints

Where mercy should have stood

And two dead left to die on snow-filled streets

Alex Pretti and Renee Good

The blonde lady’s name is Megyn Kelly. Once a top tier correspondent for Fox and NBC, today Megyn is the host of The Megyn Kelly Show, a popular podcast that appears on SiriusXM and YouTube, which the Daily Beast has likened to “a cesspit for the former Fox News star to air her more eyebrow-raising opinions.”

The surprising thing about Megyn Kelly is that she has a background in law, having graduated from Albany Law School in 1995, and putting eight years of corporate legal practice under her belt before transitioning into the world of television news reporting in 2003.

Maybe if Megyn had spend more time focusing on Constitutional law, she would understand just how intellectually vacuous her comments about Alex Pretti’s death were.

Megyn Kelly is a journalist. As such, she should have done some basic due diligence before publicly opining on a topic such as the murder of Alex Pretti by ICE agents. Had she done so, she would have been able to familiarize herself with the Complaint for Declaratory and Injunctive Relief filed in United States District Court for the District of Minnesota, where the plaintiffs characterize the situation in Minneapolis as “an unprecedented deployment of federal immigration enforcement agents from numerous agencies of Defendant U.S. Department of Homeland Security (‘DHS’)” that has “instilled fear among people living, working and visiting the Minneapolis-Saint Paul metro area (the ‘Twin Cities’)” due to “thousands of armed and masked DHS agents” who” have stormed the Twin Cities to conduct militarized raids and carry out dangerous, illegal, and unconstitutional stops and arrests in sensitive public places, including schools and hospitals—all under the guise of lawful immigration enforcement.”

The complaint states that the defendants “deployed over 2,000 DHS agents to the Twin Cities—a number that greatly exceeds the number of sworn police officers that Minneapolis and Saint Paul have, combined”, noting that this action “is, in essence, a federal invasion of the Twin Cities.”

In short, Alex Pretti was confronting what amounted to an illegal occupation of Minneapolis by armed federal agents that violated basic constitutional rights and protections under the 10th Amendment of the United States Constitution. “The Tenth Amendment gives the State of Minnesota and its subdivisions, including the Cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul, inviolable sovereign authority to protect the health and wellbeing of all those who reside, work, or visit within their borders,” the Complaint for Declaratory and Injunctive Relief declares. “Being free from unlawful seizures, excessive force and retaliation are not a list of aspirations Minnesotans deserve; these are rights enshrined within state and federal laws.”

Rights that the illegal invasion and occupation of Minneapolis by ICE agents openly violate.

Rights that Alex Pretti was defending when he was murdered by ICE agents.

Megyn Kelly preparing to go on-air while working for Fox News

Oh our Minneapolis, I hear your voice

Singing through the bloody mist

We’ll take our stand for this land

And the stranger in our midst

Here in our home they killed and roamed

In the winter of ’26

We’ll remember the names of those who died

On the streets of Minneapolis

Megyn Kelly’s words and posturing reflected more than simply an ignorance of the Constitution. The ugliness of her sentiments toward Alex Pretti exposed a poisoned core of flawed humanity that had to come from somewhere prior to her time at Albany Law.

There were hints of Megyn Kelly’s internal rot early on in her television career. In 2004, Kelly was hired by Fox News after being interviewed by Roger Aisles, the chairman and CEO. As Megyn Kelly herself admits, she wasn’t hired for her talent as a journalist or for her intellect, but rather her looks, undergoing a humiliating interview process which included doing the infamous “twirl”, which another Fox News female on-air talent said was so Aisles could “see her ass.”

“So I was asked to do the spin,” Kelly later said, “and God help me, I did it. I know people think it’s like, ‘Oh, yeah, you have to spin around.’ But I remember feeling like: I put myself through school; I was offered partnership at Jones Day, one of the best law firms in the world; I argued before federal courts of appeal all over the nation; I came here, I’m covering the U.S. Supreme Court; I graduated with honors from all of my programs — and now he wants me to twirl. And I did it.”

“If you don’t get how demeaning that is,” Megyn said, “I can’t help you. In retrospect, I’d give anything if I had said ‘no.’”

But the truth is, if she had said “no”, she most likely wouldn’t have gotten the job (it should be pointed out that Megyn Kelly claims that Aisles, two years after she was hired, tried to kiss her three times, and each time she rejected his overtures. Kelly not only kept her job, but was promoted, a sign that talent, not submission, played a role in climbing the corporate ladder at Fox.)

No one should ever be placed in the position Megyn Kelly and the other female Fox News employees were placed in. There must be zero tolerance for sexual harassment, or harassment of any kind, in or out of a place of work.

But the fact remains that Megyn Kelly was hired because she fit a certain profile, physical, emotional, and intellectual.

Roger Aisle’s may have hired her in part because of her ass.

But he also hired her because she was white, with blonde hair and blue eyes, with an emotional and intellectual disposition that was appealing to the conservative Fox audience.

What exactly this emotional and intellectual disposition represented emerged in time.

Megyn Kelly and Black Santa

Trump’s federal thugs beat up on

His face and his chest

Then we heard the gunshots

And Alex Pretti lay in the snow, dead

Their claim was self defense, sir

Just don’t believe your eyes

It’s our blood and bones

And these whistles and phones

Against Miller and Noem’s dirty lies

During an on-air segment that aired on December 12, 2013, Megyn Kelly and her co-panelists were discussing a piece in Slate written by Aisha Harris about a black versus white Santa. Kelly noted that the author was arguing that “Santa Claus should not be a white man anymore. And when I saw this headline,” Kelly continued, “I kind of laughed and thought, yeah, this is so ridiculous, yet another person claiming its racist to have a white Santa and, you know…and by the way, for all you kids watching at home, Santa just is white. but this person is just arguing that maybe we should also have a black Santa, but Santa is what he is, and were just debating it because someone wrote about it, kids.”

Megyn Kelly continued. “The author…she’s African American, and she seems to have real pain having grown up with this image of a white Santa. You know, I’ve given her her due. Just because it makes you feel uncomfortable doesn’t mean it has to change,” Kelly said. “Jesus was a white man, too. It’s like we have, he’s a historical figure that’s a verifiable fact, as is Santa, I just want kids to know that. How do you revise it in the middle of the legacy in the story and change Santa from white to black?”

Megyn Kelly’s comments ignited a media firestorm, as many well-known media personalities lashed out at the blatant racism of her comments. Two days after making her “Santa is white” statements, Megyn Kelly returned on hair and doubled down on her position. “Apparently we ignited quite a controversy the other night,” Kelly said in her opening remarks on The Kelly File. “Humor is a part of what we try to bring to this show but sometimes that is lost on the humorless.” Kelly then played a compilation of clips showing her critics, including Jimmy Kimmel, Chris Hayes, and Don Lemon, reacting to her comments.

“This would be funny if it were not so telling about our society,” Kelly said, accusing the critics of having a “kneejerk reaction to race bait.” Kelly said her comments weren’t “motivated by any racial fear,” Kelly proceeded to defend her argument that Santa is white, citing the movie Miracle on 34th Street and the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade. The blonde haired, blue eyed television host did, however, concede she might be wrong about the color of Jesus’ skin. “As I’ve learned in the past two days, that is far from settled,” Kelly admitted.

In September 2017 Megyn Kelly was hired by NBC for a high profile role on their flagship “Today” program. She was interviewed by Business Insider on November 29, 2017, where she was specifically asked whether she still believed Santa was white.

Megyn Kelly acknowledged that she “regretted a lot” of what she said while working for Fox, explaining that “if you’re going to be on the air on live television, you’re going to say stupid shit. That’s just a reality, so yeah, there’s a lot I’d like to go back and say differently.”

Megyn Kelly then proceeded not to answer the question, but rather play the victim card. “I think the lens is a truth teller, and people who watch you day after day will see who you are without the caricature of you that’s put out there by web sites and so on drooling over you One of my great struggles at Fox was that I felt that everything I did was viewed through a negative prism by those who didn’t like Fox or what it stands for, and I hated that. And I really hope that in my new position people will just see me for who I am and not through that prism. So far I feel like it’s happening. But I feel like time will tell. You’ll see me and you’ll figure out who I am, and people will accept or not accept based upon what they see, and that’s all I can ask of everybody.”

Megyn Kelly and the “Black Face” controversy

Oh our Minneapolis, I hear your voice

Crying through the bloody mist

We’ll remember the names of those who died

On the streets of Minneapolis

And watch her they did.

Little more than a year after NBC hired Megyn Kelly, she revealed her true self for all the world to see.

In a segment that aired on October 23, 2018, about political correctness and Halloween costumes, Kelly raised the issue of “blackface”, a practice dating back to the infamous minstrel shows popular in New York during the 1830’s, where white performers blackened their faces with faces burnt cork or shoe polish and, wearing tattered clothing, portrayed enslaved Africans on Southern plantations as being lazy, ignorant, and prone to thievery and cowardice.

“But what is racist?” Kelly asked. “Because you do get in trouble if you are a white person who puts on blackface on Halloween, or a black person who puts on whiteface for Halloween. Back when I was a kid that was OK, as long as you were dressing up as, like, a character.”

Later in the discussion, Kelly brought up Luann de Lesseps, a star on The Real Housewives of New York who drew a backlash in 2017 for dressing up as Ross.

“There was a controversy on The Real Housewives of New York with Luann, and she dressed as Diana Ross, and she made her skin look darker than it really is and people said that that was racist,” Kelly said. “And I don’t know, I felt like who doesn’t love Diana Ross? She wants to look like Diana Ross for one day. I don’t know how, like, that got racist on Halloween.”

America saw Megyn Kelly. America figured out who Megyn Kelly was.

And we rejected her as a racist.

Two days later Megyn Kelly was back on air, this time to deliver an apology. “I’m Megyn Kelly,” she began, “and I want to begin with two words: I’m sorry.”

With her voice cracking and her blue eyes brimming with tears, Kelly continued.

“You may have heard that yesterday we had a discussion here about political correctness and Halloween costumes. And that conversation turned to whether it is ok for a person of one race to dress up as another—a black person making their face whiter or a white person, darker, to make their costume complete. I said it seemed ok because it was part of a costume. But I was wrong, and I’m sorry. One of the great parts of getting to sit in this chair is getting to discuss points of view. Sometimes I talk, and sometimes I listen. Yesterday I learned. I learned that the history of blackface being used in awful ways by racists in this country. It is not ok for that to be part of any costume, Halloween or otherwise. I have never been a PC (i.e., politically correct) kind of person. But I do understand the value in being sensitive to our history, particularly on race and ethnicity.”

“I believe this is a time for more understanding, more love, more sensitivity and honor,” Kelly concluded. “And I want to be part of that. Thank you for listening, and for helping me listen, too.”

Megyn Kelly’s apology was too little, too late. The next day NBC terminated her show, Megyn Kelly Today. Her contact was terminated on January 18, 2019.

In her apology, Megyn Kelly talked about “learning” the history of blackface in America. As the National Museum of African American History and Culture notes on its webpage dedicated to the issue of Blackface, “Minstrelsy, comedic performances of ‘blackness’ by whites in exaggerated costumes and make-up, cannot be separated fully from the racial derision and stereotyping at its core. By distorting the features and culture of African Americans—including their looks, language, dance, deportment, and character—white Americans were able to codify whiteness across class and geopolitical lines as its antithesis.”

White Americans putting on blackface to denigrate and demean Black Americans in order to codify White superiority as a societal norm.

And yet, Megyn Kelly chose in her apology to talk about Black Americans putting on whiteface as the lead example, thereby giving something that simply never happened moral equivalency with blackface, something that did happen.

Megyn Kelly didn’t listen, and she didn’t learn.

She had been exposed as a racist, and was compelled to deliver an apology for her actions, something she didn’t really deliver on.

According to the National Museum of African American History and Culture, “blackface” was invented by poor and working-class whites who felt squeezed politically, economically, and socially “as a way of expressing the oppression that marked being members of the majority, but outside of the white norm.”

Blackface was a racist coping mechanism designed by White people to better cope with the same societal rejection that black people felt. Blackface was the poor white man’s way of feeling better at the expense of black people.

“Blackface” is a fundamental part of who and what Megyn Kelly is: an American racist.

Megyn Kelly’s 1988 graduation from Bethlehem High School

Now they say they’re here to uphold the law

But they trample on our rights

If your skin is black or brown my friend

You can be questioned or deported on sight

In chants of ICE out now

Our city’s heart and soul persists

Through broken glass and bloody tears

On the streets of Minneapolis

When discussing blackface, Megyn Kelly noted that “Back when I was a kid that was ok, as long as you were dressing up as, like, a character.”

The roots of Megyn Kelly’s racism, therefore, can be traced to her childhood. Megyn Kelly moved to the Hamlet of Delmar, New York when she was nine years old. She was a product of the Bethlehem School District (the Hamlet of Delmar is one of five Hamlets which comprise the Town of Bethlehem), and graduated from Bethlehem Central High School in 1988.

When Megyn Kelly made her blackface comments, the students of Bethlehem High School spoke up to make sure Megyn Kelly and American understood that Kelly’s words did not reflect the beliefs of the student body of Kelly’s alma mater. “Megyn Kelly has walked our halls and strolled our streets; she’s a proud member of our high school’s hall of fame, and her work has put our hometown of Bethlehem, New York, on the map,” a group of known as Students for Peace and Survival at Bethlehem Central High School wrote in an open letter. “But, as a group of young people of all different races, political beliefs and cultural backgrounds nonetheless united in fighting for a better future through a student club in her own high school, some of her recent comments have concerned us, and we hope that she hears us.”

Megyn Kelly’s comments, the students declared, “definitely do not speak to who we are in Bethlehem or at Bethlehem Central High School, from which she graduated in 1988. Blackface is not acceptable anywhere in America, and it is not acceptable in our town. We weren’t alive when Megyn was in high school but, in the recollection of many of our parents who grew up around here, it was not acceptable even in the 1980s town that she knew.”

The students then proceeded to give Megyn Kelly a history lesson about blackface and Delmar. Blackface, the students noted, “was part of a broad and sordid tradition of masking racism in the ‘humor’ of minstrelsy; people who lived in our area were not immune. Our local newspaper’s records show that minstrel shows were performed as fundraisers in our elementary school gym as late as 1960 (albeit a decade before Megyn was born). Perhaps its staying power even in the northeastern United States despite its obvious bigotry speaks to the pernicious role that blackface played and still plays in broadly normalizing racist caricatures. Jim Crow, after all, was a blackface character long before he was shorthand for systematic oppression.”

The Bethlehem students continued: “Racism might have become more subtle in the intervening years, but it remains just as potent a force in the society into which we’re about to enter as adults. The reason that Megyn’s comments about blackface being ‘OK’ when she was a kid (let alone her statement at the time that ‘I don’t know how [blackface] got racist on Halloween,’ in response to prior critics of the practice) were so offensive is that blackface is a projection of the racism that lies much deeper, and a symbol of times that are not quite as far past as we may wish to admit. As young people, we know that racial stereotyping and institutional discrimination hurts all of our futures. On race and so many other issues, our generation is waking up to a world in need of fixing — and it’s falling on us to make change happen.”

“We all have times when we use words poorly,” the students wrote, “just ask our English teachers. We cannot judge each other by our worst moments, and believe Megyn when she says that her recent comments do not speak to who she is. We know full well that one of the hardest things to do is to apologize, and we thank her for doing so. But retroactively showing ‘sensitivity’ isn’t nearly enough to prevent the cycle from continuing.”

“We must go further,” the students declared. “The solution is not sweeping these uncomfortable ideas under the rug; it’s facing them head on with appreciation for their context.”

“With more diversity of all types — on both sides of the camera — Megyn’s employer, NBC News, could approach these difficult topics with the care they deserve. By allowing America to hear the stories of those who have suffered from stereotyping and institutional racism,” the students observed, “she and they could spur important conversations. Her words carry weight like few others with those who most need to hear these stories, and whatever happens, she still has a platform that few possess. Whatever her journalistic future brings, we hope she uses it to make a real difference and bring ‘more understanding, love, sensitivity and honor’ to these issues in the future, as she promised in her apology to do.”

“There is often an idea today,” the students concluded, “that young people like us are apathetic, brainwashed into certain ideals by those above us and too disengaged to make a difference. Nothing could be further from the truth. We’re speaking for ourselves here, as our own small part in the conversation America needs to have. If there’s one thing about our generation, it’s that we do not accept the status quo. Perhaps it’s naïveté, but in a society still bearing the scars of the times of blackface, a little bit of the innocence of hope might be necessary.”

When I first read this letter, my heart swelled with pride. These kids were seven years removed from my daughters, who graduated from Bethlehem High School in 2011. I knew my daughter’s and their friends, their hearts, their thoughts, their dreams, and their aspirations. They were the “next generation” that was going to fix the mistakes they inherited from their parents.

These kids were cut from the same cloth.

They made me proud to be a resident of Delmar, proof positive that the taxes I paid for their education were not in vain.

NBC fired Megyn Kelly.

The platform Megyn Kelly was never used to correct her mistakes by shining a light on the reality of racism.

And, as Megyn Kelly’s comments about Alex Pretti demonstrates, her pledge to bring “more understanding, love, sensitivity and honor” was just another empty promise, words uttered in desperation in a vain effort to save her job.

Megyn Kelly betrayed these students, just as she betrayed Fox News, NBC, and the American people.

Just as she betrayed Alex Pretti.

Four Corners, Delmar, New York

Oh our Minneapolis, I hear your voice

Singing through the bloody mist

Here in our home they killed and roamed

In the winter of ’26

We’ll take our stand for this land

And the stranger in our midst

The roots of racism are right before our eyes.

We just have to know where to look, and the courage to see.

My family moved to Delmar, New York, in July 2000. It was a difficult move for us, because the town where we had be living—Hasting-on-Hudson—which had had been home for the past five years was a wonderful place to live, close to the excitement of New York City while retaining a quiet small-town vide, and possessing one of the best school districts in the State of New York. But economics drives decisions, and I had promised my wife that we would become homeowners once we had children of school age. We rented a house in Hastings, paying the equivalent of most mortgages for the privilege of living where we did. But when we looked into buying a 3-bedroom home in Hastings (my wife’s parents, who were refugees from the civil war in Abkhazia, Georgia, lived with us), the cost of the home combined with the associated property tax made the dream of home ownership there impossible.

My wife was insistent that we remain close to the city where our children were born (Mount Sinai Hospital is in Manhattan), so we drew a circle around the Big Apple representing a three-hour drive, and started doing our research.

The Hamlet of Delmar, New York, came out on top.

We purchased a four-bedroom two story home for less than 1/3 the cost of a three-bedroom home in Hastings. The property taxes in Delmar were 1/4 those in Hastings. Economically, the decision was a no brainer.

In 2000, the population of Delmar was 8,292, with a population density of 1,892 per square mile, more than half that of Hastings. There were 3,501 housing units, creating a density of 799 per square mile, again more than half that of Hastings.

The similarities continued when it came to demographics. In Delmar 33.3% of the households had children under the age of 18 living with them, and 60.0% of the households were comprised of married couples residing together. In Hastings these numbers were 33.8% and 57%, respectively. The median household income in Delmar was $83,219, and in Hastings, $129,227 (the difference is reflective of the proximity of New York City to Hastings, and the higher costs of living.) In both places, the percentage of residents under the age of 18 was around 25%.

These are important numbers, since income and families and children all factor into the quality of a school district, which is paramount for a family with school-age children. The Hastings-on-Hudson School District was one of the best in the State of New York.

The Bethlehem School District was even better.

There were some other similar identifying characteristics as well. The percentage of residents in Hastings who were white was 86.8%, with Blacks comprising 2.9%. In Delmar, 96.61% of the residents were white, and 1.18% Black.

I bring this up because in both Hastings and Delmar, the schools my daughters attended were nearly Lilly white in terms of their racial composition. Shortly after we moved to Delmar, I took my daughters with me while dropping off clothes for the Salvation Army. The drop-off point was located in the Arbor Hill neighborhood of the City of Albany, where 81% of the population was Black. Many of the homes in the neighborhood were boarded up, burned out, or in a general state of disrepair. Garbage was uncollected on the streets. My daughters were shocked by what they saw, and even more shocked by the concentration of Black people in the Arbor Hill neighborhood. They asked the questions one would hope they would ask—why the disparity of conditions, and why were there so many Blacks in Albany, and so few Blacks in Delmar?

I didn’t have the answers, but I promised them we would find the answers out together.

What I found was an indictment of our nation.

During the time of the Great Depression (1929-1939) housing construction collapsed. One of President Franklin Roosevelt’s top priorities was jump-starting housing construction, and in 1934 he set up the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), which ostensibly guaranteed bank mortgages intended to reinvigorate the housing construction industry, and as a result, increase the rate of home ownership.

But there was a catch—Blacks didn’t qualify.

One of the ways the FHA denied Black Americans access to these guaranteed mortgages was through what was known as “redlining”—an evaluation and subsequent evaluation of neighborhoods based upon desirability and riskiness. “Green” areas were “good”, and “Red” areas were “bad.”

In 1938 FHA agents, working collaboration with local bankers and realtors, drew up a “redlining” map for Albany. Neighborhoods where Blacks lived were universally categorized as “Red”.

“Redlining” remained in force until the 1970’s, when it was deemed illegal. But by then the damage was done—income disparity was hard-wired, with the household wealth of a typical white family ($171,000) being ten times that of a typical African American family ($17,150).

A major causal factor for this disparity was the fact that Blacks had been denied the same rights as Whites when it came to home ownership. “Redlining” encouraged poverty, and poverty beget crime.

The Arbor Hill neighborhood in Albany was a byproduct of “redlining” and, as my daughters witnessed first hand, was still haunted by the consequences of this policy decades after it was officially terminated.

Delmar never had an official “redlining” policy.

But it “redlined” nonetheless, using different tactics.

In 2005, CNN/Money Magazine named Delmar as a “Great American Town”, rating it as the 22nd “Best Places to Live” in America.

The entire Hamlet was, in effect, a “Green” zone for housing development.

Delmar was designed from scratch to be a haven for White people.

Delmar was, and is, the manifestation of how America hides its racism right before our very eyes.

Author as the Lieutenant of Delmar Engine 22, responding to the Altieri Restaurant Fire on February 14, 2009

We’ll remember the names of those who died

On the streets of Minneapolis

We’ll remember the names of those who died

On the streets of Minneapolis

I joined the Delmar Fire Department in the Summer of 2001, before 9/11 made firefighting “cool.”

I did it to serve my community and, if I’m entirely honest, to feed my need for the adrenaline that had been lacking in my life since I resigned as a weapons inspector in Iraq.

Firefighters have an intimate understanding of the community they live in and serve, especially one like Delmar, where the department combined fire and EMS response.

You get to see the community as it grows, conducting building construction surveys to understand the layout and materials used so the proper decisions could be made if the place ever caught on fire.

You got to see the community at its best during open-house events designed to encourage bonding between the department and the residents of Delmar.

And you got to see the community at its worst, responding to the myriad of emergencies that any community suffers during a calendar year. We responded to between 300-400 fire calls per years, and between 1,600-2,000 EMS calls.

Most of them were routine; many were not.

Almost every fire/EMS call put us in contact with the Bethlehem Police Department.

Early on in my time with Delmar Fire, I sensed that something was wrong. One of the fire officers whom I had grown close with was a cop in a neighboring town. He often regaled us with stories drawn from his experiences on duty—the stupidity of the criminals he arrested, and some of the more adventurous encounters. It took me a moment to realize that in every case the perpetrators he was describing were black men. One of the reasons it took me so long was that he and the others were speaking in code. “Fucking Mondays”, he would say, with everyone else shaking their heads in agreement.

After hearing him say this repeatedly, I finally spoke up. “The arrest took place Friday,” I said. “Why are you speaking about Monday?”

He looked at me, raised an eyebrow, and then looked at the rest of the firefighters, and they all broke out laughing.

“We’re not allowed to use certain words any more,” he said. “Instead of the ‘N’ word, we just call them Mondays.”

“Why ‘Mondays’?” I asked.

“Because Mondays suck.”

When the decision was made by the Bethlehem Town Board to build a Walmart Super Store in the Glenmont neighborhood next to Delmar, the Bethlehem cops protested. “Every fucking day is going to be Monday”, they said, commenting on the fact that the City of Albany was going to open up a bus route that would bring city residents to the new store.

“They’re fucking thieves. We will be spending all our time responding to shoplifting calls,” the cops complained.

The Bethlehem police department had an unwritten rule to keep “Mondays” out of the town. They patrolled the bridge over the Normans kill River that connected Albany with Bethlehem, stopping any black person who sought to walk across to inquire about what their business was in Bethlehem. “We can’t stop ‘em,” the cops said. “But we can let them know their not welcome, and that we have our eyes on them.”

When I was a Lieutenant I responded to calls out of Station Two, the “Black Sheep.” Historically Station Two was difficult to staff, since it was located far from the town center where most of the volunteers lived. But I was blessed with some great volunteers who shared my work ethic, and over time I built up a sense of esprit among my fellow “Black Sheep”; we not only started getting out of the station ahead of the Station One apparatus, but because we were getting more action, we trained hard, and were the first choice of the neighboring fire districts when it came to mutual aid.

Working with my “Black Sheep”, it became readily apparent that the racism I had witnessed extended to a general prejudice against anyone who wasn’t a straight white Christian male.

We had a great husband and wife team—he was a lawyer, she was an emergency room nurse. They took their duties seriously, attending advanced training courses and were a large part of the reason we got out of the Station as fast as we did.

During an arson investigation class, a local cop who also served as a Chief in a neighboring fire district was giving a lecture in which he referred to the act of arson as “Jewish Lightning.”

The lawyer and his wife were Jewish.

I raised my hand and asked if that was an appropriate term to be using. The cop looked at me like I was crazy. “That’s just what we call it,” he said, “The term comes from Brooklyn. Everyone uses it. We don’t mean any harm.”

The lawyer and his wife resigned shortly afterwards.

We had a great female volunteer. She was petite as hell, and I worried about her being able to perform all the tasks necessary—especially those requiring upper body strength. To qualify as an interior firefighter, each firefighter had to be able to perform a series of tasks under live fire conditions. One of these tasks was to advance a charged 2 1/2 inch down into a basement, fight the fire, and then pull an “injured” firefighter out of the basement.

I was the “injured” firefighter.

This gal muscled the 2 1/2 inch line down the stairs, using techniques I taught her that reduced the amount of upper body muscle work required. When it came time to pull me out, she did the job, step by step. She took a bad fall, but got up and persevered. When it was done, I looked at her mask and noticed there was blood inside. She had broken her nose and cut her mouth, and she needed medical attention.

But she never quit.

I took her onboard the “Black Sheep.”

But she was a lesbian.

And the rest of the fire department made fun of her behind her back.

She eventually resigned.

We had a professional firefighter from the City of Kingston move to Delmar so he could be closer to his girlfriend.

He was black.

She was white.

This guy was good, and I got him assigned to Station Two.

I had him walk through my engine set up, looking at how we packed our hoses, and discussed tactics and ways to be more efficient in our duties. His advise proved invaluable—during one response to the nearby Corning Factory, where a fiberglass production unit had caught fire, his innovation enabled us to stretch a primary and backup line and initiate attack within a few minutes of our arrival.

But Mondays suck.

Especially if they have attractive white girl friends.

The whisper campaign waged behind his back was relentless.

He resigned and moved back to Kingston.

The firefighters of the Delmar Fire Department were as dedicated a group of citizens as one could hope for.

They responded to the emergency calls for help from their fellow citizens at all hours of the day, seven days a week, 52 weeks a years.

We fought fires, mitigated floods, and saved lives.

Most of the members were Megyn Kelly’s age.

Many of them knew her when she attended Bethlehem High School.

Her faults were their faults.

They were all the product of a community designed from the ground up to be racist and discriminatory.

A place where Monday’s sucked.

And Monday’s weren’t just blacks, but anyone of color, or someone whose religion didn’t fit the Christian norm, or who’s sexual orientation wasn’t straight and white.

Yes, Delmar is one of the best places to live in America.

It’s also one of the most racist, discriminatory places to live in America.

Yesterday ICE agents raided a home in Clifton Park, detaining a family of five, including three school-aged children who attended the local schools.

The ICE agents entered the home without a warrant signed by a Judge, instead relying on an administrative warrant, making the raid a direct violation of the 4th Amendment of the United States Constitution.

This raid wasn’t an isolated act, but rather part of a deliberate policy being implemented by the Department of Homeland Security where ICE agents are told to ignore the training they received about need for judicial warrants, and to act solely on an administrative warrant signed off by their superior officer.

At some point Americans will need to decide where they are willing to draw the line when comes to defending their Constitutional rights.

Here in Lilly White Upstate New York, there is a deafening silence about what ICE has done, and what ICE is doing.

We could use a few Americans like Alex Pretti and Renee Good to assemble in the streets, cell phone cameras in hand and whistle in their mouths.

Fighting for the rights so many of their fellow citizens sacrificed their lives to defend.

And now Alex Pretti and Renee Good’s name are carved into this Pantheon of heroes.

Who will pick up their banner and lead the charge? Who among us has the courage of conviction to defend the one thing that defines who we are collectively as a nation?

The Students for Peace and Survival at Bethlehem had appealed to Megyn Kelly back in 2018 to use her platform to promote the kind of “understanding, love, sensitivity and honor” Megyn had promised to promote in the aftermath of her “blackface” scandal.

The family in Clifton Park could certainly benefit from some of the historical sensitivity toward race and ethnicity in America that Megyn Kelly claimed she had been imbued with after “learning” about racism in America.

Instead, Megyn Kelly is once again on the wrong side of history, openly mocking the death of Alex Pretti.

Alex’s crime was to stand up for the right’s of those less fortunate that him.

Of those who did not share his ethnicity.

Those who did not share his citizenship.

For those who had the same rights as he did.

Alex Pretti and Renee Good fought for all the Mondays of Minneapolis.

And now they are dead.

And the reason for Megyn’s silence cannot be swept under the carpet.

It is because Megyn Kelly is a product of the Town of Bethlehem, and the Lilly White Hamlet of Delmar.

And Monday’s fucking suck.