I believe one of the most significant recent contributions to #MMT was made at the FDR Library by L. Randall Wray in June. It was the closing keynote for the @LevyEcon

summer school.

It is now available here: https://levyinstitute.org/publications/mmt-heuristics-versus-paradigm-shift/

MMT: Heuristics versus Paradigm Shift?

(https://www.levyinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/wp_1084.pdf)

by

L. Randall Wray

Levy Economics Institute

July 2025

This is a slightly revised version of the purposely provocative keynote presented at the FDR library for

the Levy Institute Summer Seminar on Money, Finance, and Public Policy. References have been added.

The Levy Economics Institute Working Paper Collection presents research in progress by Levy Institute scholars and conference participants. The purpose of the series is to disseminate ideas to and elicit comments from academics and professionals.

Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, founded in 1986, is a nonprofit, nonpartisan,

independently funded research organization devoted to public service. Through scholarship and

economic research, it generates viable, effective public policy responses to important economic

problems that profoundly affect the quality of life in the United States and abroad.

Mainstream economics is in disarray. As Frank Hahn remarked four decades ago, “The most

serious challenge that the existence of money poses to the theorist is this: the best developed

model of the economy cannot find room for it.” He was speaking of General Equilibrium theory,

but his claim applies equally well to Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium theory, which is

used by all the major central bankers of the world to model the economy.

Let that sink in. Our central bankers use a model to understand the economy that has no money,

no banks, and no financial system. The Queen of England asked why none of the mainstreamers

foresaw the Global Financial Crisis. Their failure was baked into their model.

Remarkably, even insiders at the Fed recognize the dismal failure of orthodoxy. Jeremy Rudd

began a recent Fed research paper, claiming, “[n]obody thinks clearly, no matter what they

pretend […] that’s why people hang on so tight to their beliefs and opinions; because compared

to the haphazard way they’re arrived at, even the goofiest opinion seems wonderfully clear, sane,

and self-evident” (Rudd 2021).

He goes on to list ideas that “‘everyone knows’ to be true but that are actually arrant

nonsense”—including all the main ideas of orthodox theory. They are all nonsense. All accepted

as dogma.

To paraphrase what Keynes said a century ago, mainstream theory’s application is not only

limited to a special case (i.e., an economy that does not use money), but is also dangerous when

applied to the “facts of experience” to formulate policy. The evidence is plain to see all around

us: in an era of multiple pandemics that threaten the continued existence of human life on planet

Earth, we are stymied by imaginary constraints concocted by economists.

Over the past 30 years, Modern Modern Money Theory1 (MMT) got much of it right. Its proponents

foresaw the fatal flaws of the euro. They predicted the oncoming global financial crisis and

warned that the policy response would be insufficient, so the recovery would take much longer

than necessary. And when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, they offered a policy response—targeted

spending to address problems without setting off inflation.

In that last crisis, at least some policymakers listened to MMT. Former Congressman John

Yarmuth (D-KY), Chair of the House Budget Committee, had embraced MMT and helped to

usher through trillions of dollars of pandemic relief without worrying about “pay-fors.” As he

correctly argued (as quoted in Wray 2021), “Historically, what we’ve always done is said, ‘What

can we afford to do?’ And that’s not the right question. The right question is, ‘What do the

American people need us to do?’ […] Once you answered that, then you say, ‘How do you

resource that need?’”

He went on to argue that, as the US government issues its own currency, finance is never the

problem. What matters is resource availability.

As MMT predicted, trillions2 of dollars of deficits did not cause interest rates to spike, or the

dollar to crash, or attacks by bond vigilantes, and did not force the US government to default.

All the finance was keystroked, all the treasury’s checks cleared, all the bonds were taken-up,

and the dollar remained strong. The deepest recession on record was reversed with the fastest

recovery. MMT was in the news, again, but this time occasionally with a positive spin. The

pandemic response was claimed to be the first real world experiment that applied MMT.

However, the pandemic lingered on longer than most expected—with continued supply chain

disruptions, new viral outbreaks, organized political resistance to science, and price-gouging by

mega-corps with pricing power.

Inflation rose. MMT was blamed. In truth, the policies were not what we advocated—spending

was not well-targeted, jobs were not created directly, capacity was not enhanced.

As Yarmuth warned, all eyes need to be focused on resources, not on finance.

A chief architect of the neoliberal world order, Larry Summers, announced with fury that he was

offended that the “newspaper of record” would devote space to MMT: “I am sorry to see the

nytimes taking MMT seriously as an intellectual movement. It is the equivalent of publicizing

fad diets, quack cancer cures or creationist theories.”3

Jason Furman—a favorite of Democratic administrations—fumed: “I don’t think MMT makes

any sense. I also don’t think it’s played a role in shifting us on deficits.”4

And now, of course, we are back to the deficits—two of them (trade and government budget),

both chronic, both seemingly intractable problems. As I have explained,5 the two are inextricably

linked, although not in the way that conventional analysis claims.

I do think they have become a problem and I think MMT needs to clearly address them. Too

often MMT proponents have responded to critics with simple heuristics—a list of talking points

that are meant to represent descriptions of reality—freed of theory or policy recommendations.

While heuristics are useful in introducing MMT to beginners, they cannot substitute for careful

economic analysis. We might have relied on them excessively.

Let me give some examples of problematic heuristics:

• Taxes drive money

• Government spends currency first, then taxes it back

• Imports are a benefit, exports are a cost

• Bond sales are just a reserve drain

• Government sets the price level

• Floating exchange rates maximize domestic policy space

• There’s no financial crisis so great that fiscal policy cannot resolve it

While there’s a kernel of truth in each, all are historically, theoretically, and practically

problematic. Each follows logically from carefully constructed assumptions. None strictly

applies to the economy we actually live in.

It is often said that MMT is mainly a description of the way things work—and that theory and

policy can be added as desired. I’ve even said (Wray 2024a) that MMT is for Austrians, too!

I want to walk that back. Description without theory is not possible. Theory without a paradigm

is not possible. We need a paradigm to formulate theory, and a theory to formulate description.

Once we have got all that, only then we can tackle policy.

Both the University of Missouri—Kansas City and the Levy Institute have played a big role in

the development of MMT and share a paradigm that has shaped our approach. I’ll briefly outline

the building blocks:

• From Marx, Keynes, Veblen, Minsky: Marx’s M-C-M’; Keynes’s Monetary Theory of

Production; and Veblen’s Theory of Business Enterprise.

• From the Institutionalists (Veblen and Minsky): money is all bound up with power: to do

good and bad; Money is the most important institution in Capitalist Economy

• From the (Post) Keynesians (Keynes, Davidson, and Minsky): money and uncertainty;

Money and contracts; Holding money “quells the disquietude” (as Keynes put it);

Endogenous money

• From the Chartalists (Knapp, Innes, Goodhart, and Minsky): state money and currency

sovereignty

• From Functional Finance (Lerner and Minsky): state money and the approach to fiscal

and monetary policies

• And, finally, the Sectoral Balances approach (Godley and Minsky): focus on balance

sheets and macro balances; balances do balance!

TOGETHER: that is MODERN MONEY THEORY

As Minsky used to say, a general theory is useless. While Keynes called his revolutionary book

The General Theory, Minsky argued it to be a misnomer—it is a theory of the capitalist economy

where money plays a special role.

James K. Galbraith has argued that Keynes purposefully borrowed his title from Einstein as he

was trying to do for economics what Einstein had done for physics.

But economies are far more complicated than the physical world. Many heterodox economists

argue that biology is a better analogy because the living world is always evolving—from a past

that we can sort of understand to an unknowable future. That better captures what Keynes was

doing—a Darwinian Revolution.

As Minsky insisted (Wray 2017), capitalism evolves—there are 57 varieties—and our theory

must continually evolve along with the facts of experience.

Money is at least 5,000 years old, as David Graeber (2012) claimed, and its role changed

significantly over those thousands of years. For most of economic life, money didn’t matter

much—until modern capitalism was incubated by the New World’s slavery on the backs of

captured Africans.

All the modern institutions we associate with capitalism came out of slavery—modern finance,

administration, accounting, labor discipline, policing, and warfare, as well as the peculiar form

taken by American democracy (Wray 2025a).

Thus, our theory needs to be institution-specific. Our paradigm is monetary production: unlike in

all previous economic systems, the purpose of production—from the perspective of those in

control—is to start with money to end up with more money. Satisfaction of needs is not the goal

of those who control capital.

We need a countervailing power—to use Galbraithian (1956) terminology—to ensure that needs

are met, which can include government, labor unions, and social service organizations.

Government in capitalist economies has always served two masters—the capitalists and the rest

of us.

Left to its own devices, capitalism is highly unsustainable—economically, socially,

environmentally, and politically. Unlike tribal society—which could sustain itself for thousands,

maybe millions of years—capitalism would self-destruct within a generation if it were

abandoned to the invisible hand.

That is what we saw, with depression after depression, once every generation until Roosevelt’s

reforms and the creation of Big Government with what Minsky called Managerial Welfare State

Capitalism and what Galbraith called the New Industrial State.

In its modern guise—which we can date to 1870 (what Robert Gordon uses as the date for the

beginning of the “special century”)—capitalism has gone through four or five stages according

to Minsky. This final stage, Money Manager Capitalism, has run its course. We stand at the edge

of a cliff, with no bottom in sight.

Trump wants us to jump off.

Let me return to the heuristics to explain why I believe they present obstacles to further advances

in MMT. I am only going to tackle a handful of them here—but I think that many others also

need to be critically assessed.

Taxes Drive Money. We have often used the metaphor of the colonist who imposes a tax in his

own currency and enforces payment with his gun. There are certainly historical examples, in

Africa for example.

And we often use the American colonies—that would pass two bills, one imposing a new tax and

the other authorizing the issue of paper currency. All this is true. But money already existed—

this cannot be an origins story and doesn’t shed the proper light on its nature.

Money has existed for 5,000 years at least. As best as we can determine from historical evidence,

it was invented as a unit of account to measure debts, for internal record keeping in the temples

of Babylonia (Hudson 2018). This was before evidence of taxes or markets.

What difference does this make? The first draws attention to illegitimate force—the evil

colonizer. More importantly, it emphasizes money as something that exchanges hands:

government spends a currency that then can be used to pay taxes, make purchases in markets, or

hoard for later use.

The second emphasizes record keeping, credits and debits. Modern governments do not spend

physical currency, and taxpayers use only trivial amounts. Most of it is outside the US—used for

illegal activity. Young people today have never bought anything except by flashing their smart

phone.

And the US government never spends currency, at least in America. Washington spends cash

when they invade a country and want to pay mercenaries or bribe officials.

I used to make fun of a prominent Post Keynesian who objected to MMT before a roomful of

legal historians, saying: “I never think of taxes when I accept a US dollar—I accept dollars

because I want to buy ice cream.” We all laughed at the superficial critique of MMT’s claim that

taxes drive money.

But the complaint resonates with 99 percent of the population—who never think of taxes as

driving their demand for money. They want ice cream. And they don’t use currency to buy it.

We need to move away from thinking about money as something that goes from hand to hand.

The better metaphor is the baseball scoreboard, with banks replacing the Babylonian temple as

the score keepers. Money isn’t something that you have or do not have. It is all about keeping

track of debits and credits. And, as Minsky said, anyone can create money—the problem is to get

it accepted. The question is whether the scorekeeper will give you a credit.

As Minsky said, banks are not money lenders. They make payments for their customers. The

“money” is created when they make the payment. Banks follow rules to determine whether they

will make a payment for you. And they tally up what you owe—just as the Devil tallies your sins

to determine whether he takes your soul.

The central bank is the scorekeeper for the scorekeepers, and also for the government. It also

follows rules that determine when and how it will make payments for banks and the treasury.

Money is not something of which the government, the central bank, banks, or you can run out.

As Mat Forstater says, the dollar is like the inch (or centimeter)—we cannot run out.

I want to address three additional areas where I think overly simplistic logic leads down the

wrong path—at least when it comes to developing an understanding of the way our form of

capitalism works.

First, there is the claim that as monopoly supplier of the currency, government can set any and all

prices. The logic follows from the taxes-drive-money assumption. By imposing an obligation on

you, government determines what you must give up to get the currency to pay your tax. As I

have argued (Wray 2024b), this sounds a lot like the labor theory of value: if it takes an hour to

earn a dollar, then the dollar is worth an hour of labor.

This is the main idea behind the buffer stock approach to the job guarantee: government can

maintain a buffer stock of workers paying a base wage to prevent the wage from falling and

“selling” labor to private employers at a markup over that.

By analogy, government can do the same for every other thing bought and sold.

Well, what would that look like in the real world? A real mess. People joke about the Soviet

Union’s attempt to regulate market prices but this would be that on steroids.

It is completely inconsistent with capitalism.

And as I have tried to make clear (Wray 2024b), the basic wage—the wage for ordinary labor—

will not map directly to price. Capitalism operates according to a logic that generally tries to

equalize rates of profit and exploitation—not according to the whims of a government that wants

to set all prices.

The second claim—that we can always counter a financial crisis by ramping up fiscal policy is

wrong for the kind of financialized economy we had both in the gilded age before the Great

Depression (often called Finance Capitalism) and since the unraveling of the New Deal

institutions—beginning in the 1970s. This Money Manager Capitalism stage, with everything

financialized is—to use the metaphor again—finance on steroids.

The Fed spent and lent $29 trillion dollars to save global finance (Felkerson 2011). The next

financial crisis might take even more.

You could say: well, just let the whole darned financial system fail. The real economy will still

be here. That’s what we did in the Great Depression. As Minsky used to say: yes, the economy

might recover, but by way of hell first.

To be clear, I don’t support the way the Fed responded—it was a mess, much of it was illegal,

and none of Wall Street’s criminal class was prosecuted. The money managers came roaring

back and rebooted the bubblicious economy.

But merely ramping up a fiscal response, alone, wouldn’t have saved our pension funds, our

investments in our houses, or our university endowments. Even excluding all the fancy

derivatives and other crazy financial products that total up to the hundreds of trillions of dollars,

we have financial assets that are at least five times greater than the so-called real economy.

We have to keep in mind that, in capitalism, the financial is more real than the real. This is a

system based on producing money value, not one directed at satisfying needs.

I’d like to change that—but we need to approach it sensibly, not by bringing on another Great

Depression.

Finally, there’s the MMT dismissal of the twin deficits problem. Since government cannot run

out of money, budget deficits aren’t a problem—we might as well run them up. With a floating

currency, trade deficits are a sign that we are winning: we get the stuff, they only get dollars.

Trump says we are losing; MMT says we win.

Minsky’s writings during the Reagan years showed great concern about both deficits. This has

led some MMT proponents to argue that Minsky cannot be a guiding light for MMT. I have

discussed Minsky’s views on this in two Levy publications (Wray 2018; 2025b). Let me quickly

summarize his points.

Creation of a large and chronic trade deficit means—by the sectoral balances identity—that we

will have a large and chronic budget deficit.

Minsky was worried that rival currencies could substitute for the dollar, so its value could fall—

potentially irreversibly—forcing the Fed to keep interest rates high, while also putting inflation

pressure on the US. The combination could lead to secular stagnation.

What we saw, however, is that our two rivals—Germany and Japan—both dropped out of the

running.

Germany committed suicide by joining the euro and embracing austerity; in part because the government also embraced austerity in an attempt to balance the budget.

In the meantime, the US lost its industrial advantage (first to Germany and then to Asia). This

was only partially due to trade—it had more to do with financialization of the economy—but

contributed to inequality, the weakening of labor unions, and the rise of neoliberalism.

We did get the secular stagnation that Minsky warned of, only relieved by serial bubbles—as

Michael Hudson (2014) said, we became a Bubbles-R-Us economy. Propped up by serial

bailouts by the Fed and growing budget deficits.

For two decades, the Fed kept rates low, fueling the bubbles, but since COVID, the Fed has kept

them high. And that means—as Minsky warned—that more and more of government’s spending

is inefficient—going to interest and transfer payments, with much of the spending going abroad.

The joke is that Uncle Sam is now just an army with a welfare system attached to it. Contrast all

the recent presidents with FDR: his government made America great. His accomplishments are

still all around us.

Reagan successfully convinced us that government is a problem, not a solution—and the

Democrats have largely reinforced that belief by doing little to nothing to help the working class

(Tcherneva and Wray 2025).

And, yet, the DOGE tech boys could not find any waste because we have created the most

efficient way to run an inefficient system.

As I said earlier, Minsky worried about secular stagnation. We temporarily staved that off during

the Clinton years and for some time after by boosting finance—to the benefit of the FIRE sector

(finance, insurance, and real estate) and what Citigroup (Kapur, Macleod, and Singh 2005) called

the new Plutonomy—those billionaires who have taken over the government and the economy.

A handful of counties around the US boomed while most of the country got left behind and

turned red—as Pavlina Tcherneva and I have shown (2025)—even as Trump and Musk try to

turn the country into a banana republic, with Trump’s favorability rating somewhere around 40

percent, the approval rating of the Democrats is stuck at 27 percent.

A major exception to the stagnation was Silicon Valley: over the past two decades, tech is the

sector that boomed alongside Wall Street. Interestingly, some of the early tech firms were

involved in the payments system. That has come full circle with the second coming of Trump.

This is, I think, the true aim of DOGE—to merge the financial and tech sectors, to financialize

our data.

We no longer live in a world of production of commodities by means of commodities6—

including, most importantly, labor power. Capitalism is still driven by the quest for “more

money” but the main source is not production of commodities. The labor theory of value doesn’t

strictly apply: monetary wealth has been freed from production. Neither income nor profit flows

are important for our plutocrats—as investigations by ProPublica (Eisinger, Ernsthausen, and

Kiel 2021) have shown. Billionaires like Musk pay no income taxes because they have no

income.

Data is now the most important commodity in the world and DOGE has apparently developed

the capacity to merge all the data collected by the government (including the IRS), banks, social

media, and the insurance sector—especially health managers that deny your claims and startups

that have your DNA and all other health records—into a one-stop shopping mall for sale to the

highest bidders (Randles 2025; Chayka 2025).

DOGE got hold of the payments system and can push the red stop button on any payment. They

tested it on New York City—they actually shut down payments that Congress approved to help

with the costs created by the clown governor of Texas who bussed immigrants and dumped them

on the city (Tankus 2025).

The Trump administration has paid over $100 million to Palantir (Frenkel and Krolik 2025) to

consolidate all the government’s data on individuals, presumably to make it easier to go after the

millions of Americans who could be added to an enemies list. To use the metaphor one more

time: this could be Nixon’s enemies list on steroids.

Am I paranoid? It is a strange new world. Capitalism is a system based on exploitation. While

Marx focused on exploitation of labor, capitalism also exploits the environment, the family, the

“others” outside its system. But the proponents of tech foresee a near-future in which labor is no

longer needed as AI increasingly takes over all tasks.

They don’t need your labor, they need your data, and maybe your eyeballs.

AI’s most important task now is to accumulate all the data in existence. What then? It will know

everything we know; it will be able to do everything we can do. And MMT teaches that it will be

able to afford to do so.

Maybe we should keep that a secret?

But I don’t want to end on that note. Let me conclude.

Conventional macroeconomic theory—of both the orthodox and (unfortunately) of much of the

heterodox variety—takes an excessively “high in the sky” view.

Unemployment is caused by too little spending. Inflation is caused by too much. Keeping taxes

aligned—more or less—with government spending ensures it will not be inflationary. The

solution to inflation is to cut spending or raise taxes.

MMT is dangerous because it lets the cat out of the bag: taxes do not finance government

spending. This gives politicians a license to run up spending that will cause inflation. Best to

keep the wool pulled over the eyes and insist on tax “pay-fors,” or let the DOGE boys stop the

payments.

MMT’s view is different. The composition of both taxes and spending matters, and so there are

two reasons that trying to match them is misguided: (1) government doesn’t need the revenue,

and (2) there is no reason to believe that matching them means government’s impact approaches

neutral.

Spending on unemployed resources puts them to work with little inflationary consequence.

Spending on a fixed price-floating quantity basis reduces further the inflationary danger. (That is

what the Job Guarantee does.)

Spending to increase productive capacity also reduces the danger of inflation, and can raise the

danger of deflation. Clearly, no tax hikes are required in that case—we might need tax cuts if

productive capacity grows to exceed what can be supported by spending.

A good example is healthcare: Medicare for All would cut spending in half—from over 18

percent of GDP to perhaps 9 percent, the amount typically spent by other rich countries (Wray

and Nersisyan 2020). We would need a big tax cut to offset the disinflationary impact.

Likewise, it matters what kind of tax is imposed. A financial transactions tax, or a billionaire

wealth tax, or a tax surcharge on millionaires is unlikely to take a significant amount of demand

out of the economy—no matter how much revenue they raise—so are not likely to reduce

inflation (Wray and Nersisyan 2020).

Forget billionaire taxes to raise revenue. Instead, tax billionaires to destroy their wealth—impose

a 120 percent wealth tax to take all of it, and send them a bill for the rest. Incentivize them to try

to work their way out of the debt.

On the other hand, a broad-based income or consumption tax will reduce demand significantly.

Other methods can also be used if desired: rationing, patriotic saving, or postponed consumption.

All this is important to support a transformative Green New Deal—or any other large scale

government initiative. As Yarmuth insisted7, we need to identify the resources needed and then

release them from current use as necessary.

We can use taxes for that purpose, although we might need to include other methods—such as

banning oil drilling and fracking, or conscripting resources—to obtain the resources needed for

the public purpose.

We then spend to put those resources to use. If we have matched resources to purposes well, then

there will be no significant inflationary pressures no matter the budgetary outcome.

This sort of analysis must be undertaken, but it scares both orthodox and heterodox economists

accustomed to relegating decision-making to the “invisible hand” of the market.

Yes, planning will be required. Yes, it is difficult. Yes, mistakes will be made. But there is no

alternative.

A half-century of neoliberalism has brought the world to the brink of collapse. Only concerted

effort and cooperation by the world’s governments provides any chance of survival.

Understanding MMT does not make this easy. But it helps us to recognize what the true

constraints are: resources, initiative, politics, imagination.

And whatever it is that AI plans to do with us.

REFERENCES

Chayka, K. 2025. “Techno-Fascism Comes to America.” The New Yorker, February 26, 2025.

https: //www.newyorker.com/culture/infinite-scroll/techno-fascism-comes-to-america-

elon-musk

Eisinger, J., J. Ernsthausen, and P. Kiel. 2021. “The Secret IRS Files: Trove of Never-Before-

Seen Records Reveal How the Wealthiest Avoid Income Tax.” ProPublica, June 8, 2021.

https://www.propublica.org/article/the-secret-irs-files-trove-of-never-before-seen-

records-reveal-how-the-wealthiest-avoid-income-tax

Felkerson, J. A. 2011. “$29,000,000,000,000: A Detailed Look at the Fed’s Bailout by Funding

Facility and Recipient”, Levy Economics Institute Working Paper Series, No. 698.

https://www.levyinstitute.org/publications/29000000000000-a-detailed-look-at-the-feds-

bailout-by-funding-facility-and-recipient/.

Frenkel, S. and A. Krolik. 2025. “Trump Taps Palantir to Compile Data on Americans.” The

New York Times, May 30, 2025.

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/05/30/technology/trump-palantir-data-americans.html

Galbraith, J. K. 1956. American Capitalism: The Concept of Countervailing Power. Houghton

Mifflin.

Graeber, D. 2012. Debt: The First 5000 Years. Melville House: New York.

Hudson, M. 2014. The Bubble and Beyond. Islet-Verlag: Dresden.

Hudson, M. 2018. “Palatial Credit: Origins of Money and Interest.” On Finance, Real Estate,

and the Powers of Neoliberalism, published April 6, 2018. https://michael-

hudson.com/2018/04/palatial-credit-origins-of-money-and-interest/.

Kapur, A., N. Macleod, and N. Singh. 2005. “Equity Strategy: Plutonomy: Buying Luxury,

Explaining Global Imbalance.” Citigroup, Industry Note.

https://delong.typepad.com/plutonomy-1.pdf

Randles, J. 2025. “23andMe’s Bankruptcy Puts 15 Million Users’ DNA Info on Auction Block.”

Bloomberg, March 24, 2025. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-03-

24/23andme-s-bankruptcy-puts-15-million-users-dna-info-on-auction-block

Rudd, J. B. 2021. “Why Do We Think That Inflation Expectations Matter for Inflation? (And

Should We?)” Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2021-062. Washington: Board

of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. https://doi.org/10.17016/FEDS.2021.062

Tankus, N. 2025. “Can Trump Arbitrarily Take Money From Anyone’s Bank Account?” The

Rolling Stone, March 13, 2025.

https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-

features/trump-musk-doge-treasury-take-money-bank-account-1235295232/

Tcherneva, P. R. and L. R. Wray. 2025. “’That “Vision Thing’: Formulating a Winning Policy

Agenda.” Levy Economics Institute, Public Policy Brief No. 158.

https://www.levyinstitute.org/publications/that-vision-thing-formulating-a-winning-

policy-agenda/

Wray, L. R. 2017. Why Minsky Matters: An Introduction to the Work of a Maverick Economist.

Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ. http://press.princeton.edu/titles/10575.html

Wray, L. R. 2018. “Functional Finance: A Comparison of the Evolution of the Positions of

Hyman Minsky and Abba Lerner.” Levy Economics Institute Working Paper Series, No.

900. https://www.levyinstitute.org/publications/functional-finance-a-comparison-of-the-

evolution-of-the-positions-of-hyman-minsky-and-abba-lerner/

Wray, L. R. 2021. “What Is MMT’s State of Play in Washington?” E-Pamphlets, August 2021,

Levy Economics Institute, https://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/e_pamphlet_2.pdf

Wray, L. R. 2024a. Modern Money Theory: a primer on macroeconomics for sovereign

monetary systems, 3rd edition, Palgrave Macmillan.

https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-031-47884-0

Wray, L. R. 2024b. “The Value of Money: A Survey of Heterodox Approaches.” Levy

Economics Institute Working Paper Series, No. 1062.

https://www.levyinstitute.org/publications/the-value-of-money/

Wray, L. R. 2025a. Understanding Modern Money Theory: Money and Credit in Capitalist

Economies. Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK.

Wray, L. R. 2025b. “Ratings Agencies Downgrade the Dollar’s Exorbitant Privilege.” Levy

Economics Institute, Policy Note 2025.

https://www.levyinstitute.org/publications/ratings-agencies-downgrade-the-dollars-

exorbitant-privilege/8

Wray, L. R. and Y. Nersisyan. 2020. “Can We Afford the Green New Deal?” Levy Economics

Institute Public Policy Brief No. 148.

https://www.levyinstitute.org/publications/can-we-

afford-the-green-new-deal/

oooooo

Ratings Agencies Downgrade the Dollar’s Exorbitant Privilege

They are at it again. Moody’s has finally joined the other two ratings agencies in downgrading US government debt. Standard & Poor’s downgrade was first in 2011[1], while Fitch waited until 2023. Now they unanimously give US budgeting a vote of no confidence.[2] They’re sending the message that America must get its fiscal house in order to preserve confidence in the dollar—the premier currency that underlies the global financial system.

In this note, we will first address the issue of rating sovereign government debt: Do the credit raters know how to do it, and does it make any sense to do it? We will conclude that the answer to both is “no.” We then turn to possible negative impacts of government deficits and debt—and assess how likely it is that the US faces them. Finally, we address the claim that the dollar has provided an exorbitant privilege to the US and whether that may be coming to an end.

How Should Sovereign Debt Be Rated?

Many see downgrading of credit ratings of sovereign debt as a warning shot across the bow to “get your budget under control.” But while downgrades have become more or less routine, they have never had much impact on budgetary outcomes of sovereign governments—the countries continue to run deficits and run up the debt ratios. In the early 2000s, the raters downgraded Japan and by the end of the decade, downgraded the US. Each time, it made the news and provoked some finger wagging, but both the US and Japan continued down the path that supposedly leads to rack and ruin.

Each time, the raters also faced pushback—by the downgraded governments as well as by a handful of critics, including yours truly. Back in 2002, I tried to get to the bottom of their justification for downgrading Japan. I summarized my findings as follows:

As a report from Mizuho Securities says, “Moody’s and other prominent foreign credit agencies have used historical default ratings for corporate entities…. On the other hand, regarding sovereigns (particularly highly rated OECD countries) there is a lack of data which would provide a statistically (sic) explanation as it does for the corporate sector.”[3] John A. Bohn, president of Moody’s, explained that a “rating is at bottom an opinion. At Moody’s Investors service…. This opinion is defined as the future ability and legal obligation of an issuer of debt to make timely payments of principal and interest on a specific fixed-income security. Our rating measures the probability that the issuer will default on the security over its life….”[4] He went on to argue that the likelihood of default for an Aa2-rated debt should be the same across issuers, without regard to “a borrower’s country, industry, or type of fixed-income obligation”.[5]

Clearly, the primary consideration used in determining whether to downgrade sovereign debt—or any other debt—must be an assessment that risk of default has increased. And Japan’s default risk had supposedly risen because its persistent government deficit had increased “fiscal strains” by raising debt-to-GDP ratios. However, no “highly rated OECD” country has defaulted on its debt.[6] It is hard to put probabilities on something that never happens.

When the ratings agencies downgraded US government debt in 2011, the New York Times invited eight critics to contribute editorials.[7] It is interesting to read these in the light of the budgetary history of the following 14 years.

Tyler Cowen predicted: “Standard and Poor’s tried to send Washington a wake-up call, but will this work? Probably not.” He went on, seemingly agreeing that the raters were correct to worry about solvency: “It’s a common argument that the U.S. need not worry about its borrowing because interest rates on Treasury debt are so low. That’s a mistake. The low rates mean that investors expect to be paid back; they don’t mean that U.S. debt levels are healthy.”

Barry Eichengreen argued: “The ratings agencies don’t know anything more than people who have read newspapers covering this issue. They don’t influence market sentiment as much as they reflect it. In saying that U.S. policy makers may not be able to meet the country’s medium-term budgetary challenges by 2013, they are not telling us anything we don’t already know…. As I note in my book, Exorbitant Privilege, the resulting political gridlock and uncertainty could be the catalyst for mass flight away from U.S. treasury bonds. If so, the dollar would crash. Interest rates would spike. Important institutional investors could be caught flat-footed. This could make the last financial crisis look like a walk in the park.”

Arnold Kling offered a dystopian prediction: “If we have a crisis, it will occur suddenly as markets reach a tipping point, taking people by surprise. To me, the important thing to keep in mind is that some people’s expectations for their future retirement will have to be disappointed. Government obligations, including worker pensions, Social Security, and Medicare, are underfunded. Government may renege on its promises. If instead it tries to keep its promises, it will probably have to confiscate the wealth of those who are trying to provide for their own retirement. One of those unpleasant scenarios, or a combination of the two, is fairly certain to occur.”

Mark Thoma wrote: “I am more worried about who will be asked to pay the costs of reducing the long-run debt to a more manageable level. Will we balance the books on the backs of those least able to pay and least able to defend themselves in the political process — the sick, the poor, the elderly and children? Or will we ask those higher up on the income and wealth ladders to pay a significant part of the bill? The main worry about the debt is that, at some point in the future, interest rates will rise as the world becomes reluctant to lend more to us. A rise in interest rates would lead to reduced investment, growth and employment. The decisions over how to distribute the pain are likely to involve intense political conflict.”

Yves Smith chastised the raters: “The United States is simply not at risk of default. Default is impossible for a sovereign currency issuer. The Standard & Poor’s rating firm should be embarrassed. If there is any political judgment at work here, it is S.&P. falling for politically motivated scare mongering. But given its track record with mortgage securities and collateralized debt obligations, why should we be surprised to see a rating agency relying on conventional wisdom rather than analysis?”

Finally[8], Barry Ritholz said: “I have stopped paying any attention to anything that S.&P. says or does. Its performance over the past decade has revealed it to be incompetent and corrupt – it sold its AAA ratings to the highest bidder. It is the broker who lost all your money, the girlfriend who cheated on you, the partner who stole from you…. The current debate about deficits looks like more politics…. The deficit has been with us for a long time. Since investors are continuing to lend money to Uncle Sam at exceedingly low rates, there does not appear to be any real fear of a default. That is what matters most to bond buyers — and it why I never care what S.&P. thinks on this.”

I also criticized the raters in my contribution[9] (and also in a much longer piece[10]),

In what appears to be an attempt to influence the political debate in Washington over federal government deficits, Standards & Poor’s rating firm downgraded U.S. debt to negative from stable. Yes, the raters who blessed virtually every toxic waste subprime security they saw with AAA ratings now see problems with sovereign government debt.

I went on to argue that we could ignore them for two reasons: they don’t know what they are doing and their ratings of sovereign debt have no economic impacts. I cited the earlier downgrading of Japan, summarizing the outcome:

A decade ago Moody’s downgraded Japan to Aaa3, generating a sharp reaction from the government. The raters back-tracked and said they were not rating ability to pay, but rather the prospects for inflation and currency depreciation. After 10 more years of running deficits, Japan’s debt-to-gross-domestic-product ratio is 200 percent, it borrows at nearly zero interest rates, it makes every payment that comes due, its yen remains strong and deflation reigns.

The truth is that the raters only have expertise in rating municipal bonds and have failed spectacularly when trying to expand their business to rate tranches of mortgage-backed securities[11] as well as sovereign government debt. To put it as simply as possible: they do not understand what is different about sovereign government debt—that is, there is no risk of involuntary default, so “credit” rating is not applicable. To be sure, in the case of the US, there is a possibility of voluntary default because Congress has imposed a debt limit on the Treasury. So, there is a political risk that Congress might choose to default on payment commitments rather than raise the debt limit. Perhaps this should be assessed—but not by credit raters. To paraphrase Keynes, even considering a voluntary default should “be recognized for what it is, a somewhat disgusting morbidity, one of those semi-criminal, semi-pathological propensities which one hands over with a shudder to the specialists in mental disease.” [12]

In that earlier piece, I explained that a sovereign nation that issues government debt denominated in the home currency will never have trouble “making timely payments” so long as it lets its currency float. Sovereign national governments spend by having their central bank credit banking system reserves, with private banks crediting the deposits of recipients. Hence, the large Japanese fiscal deficits resulting from government purchases and interest payments would have led to large reserve credits for the banking system. If nothing further were done, these credits would just sit in the banking system as excess reserve holdings. However, most of the created excess reserves are normally drained from the banking system through treasury sales of new JGBs—as the treasury and central bank coordinate activities to minimize impacts of fiscal operations on banking system reserves. The result of such sales is to provide banks with an interest-earning alternative to non-interest-earning bank reserves. (It is telling that, in spite of the largest budget deficits among OECD nations, Japan’s overnight interest rate was for a long time the lowest.)

The government could at any time stop issuing new sovereign debt and simply leave more excess reserves in the system. This would also reduce the government’s net interest payments. Given the state of the Japanese economy, such a policy would likely depress growth further due to a loss of government interest payments that generate private income. Nor is it likely that the government would ever need to pursue such a policy, for the banking system would almost assuredly prefer earning assets over non-earning excess reserves. But in any case, the government would always be able to pay interest (and roll-over principal) simply by crediting bank reserves.

I argued that one can think of sovereign debt as nothing more complicated than reserves that pay a higher interest rate. In all modern nations that operate with a domestic currency and a floating exchange rate, governments spend by issuing reserves without promising to convert those reserves to anything. This is quite different from a nation that operates on a gold standard, with a currency board, or on a fixed exchange rate, in which case the government essentially promises to exchange reserves for gold or a foreign currency at a fixed exchange rate. Such a nation faces the possibility that it will run out of the required gold or foreign currency reserves—in which case it will be forced to default on its promise to convert. However, countries like the US and Japan do not promise to convert reserves of dollars or yen (respectively) to anything at a fixed exchange rate. Hence, there is no possibility of default on reserves, and because sovereign debt issued by a US or a Japan is really nothing more than reserves that pay interest, there is no greater possibility of default on sovereign debt than on central bank reserves. It makes as much sense to rate Japanese government home currency debt as it would to rate the Bank of Japan reserves held by the Japanese banking system.

Note that since 2009 the Fed has paid interest on reserves, and like many other countries in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis, bought up trillions of dollars’ worth of government bonds (and mortgage-backed securities). The Fed still has a large stock of bonds and is making huge payments of interest on reserves held by banks. And yet we don’t see the credit ratings agencies evaluating the risk that the Fed will default on its promise to pay interest. If it did default, that would lower the profitability of the banking system. Could one imagine that a ratings agency would downgrade the banking systems of the US or Japan out of fear that their central banks might default on the promise to pay interest on reserves?

Returning to the 2011 New York Times editorials discussed above, the fears and prognoses of Cohen, Eichengreen, Thoma, and Kling look a bit quaint. The US Federal government has added trillions upon trillions of dollars of additional debt, consistently ran deficits—ramped up tremendously during the COVID crisis—and made all payments as they came due, even as Moody’s has joined the naysayer’s club by downgrading the debt.

Is There Any Downside to Sovereign Deficits and Debt?

Does this mean that we should never worry about government deficits or sustained growth of government debt ratios? No, it doesn’t, although most of the fears about consequences are overwrought or misplaced: interest rate effects, “crowding out” of private spending, inflation, and exchange rate effects. I will be brief on rebutting the conventional views, but as I argue in the final sections, this does not mean that we should ignore possible negative consequences.

The beliefs that government deficits raise interest rates and that deficits “crowd out” private spending—especially investment—are linked and based on a flawed view of interest rate determination. Outdated, orthodox theory relies on either the loanable-funds approach or the IS–LM model. While these differ in assumptions, both conclude that bigger budget deficits raise interest rates (either because government competes for scarce saving to “borrow,” or because deficits increase income that raises the demand for money). It is now recognized, however, that central banks set the base rate (i.e., the fed funds rate in the US) while longer-term interest rates are linked to that, but more complexly determined. Expectations of future central bank policy play a major role (if the central bank is expected to raise its target in the future, that will tend to increase the long-term rates now), although expected exchange rate movements and preference for liquid positions also matter. While a central bank could target a longer rate (say, the 10-year treasury bond rate), central banks usually do not do that explicitly.

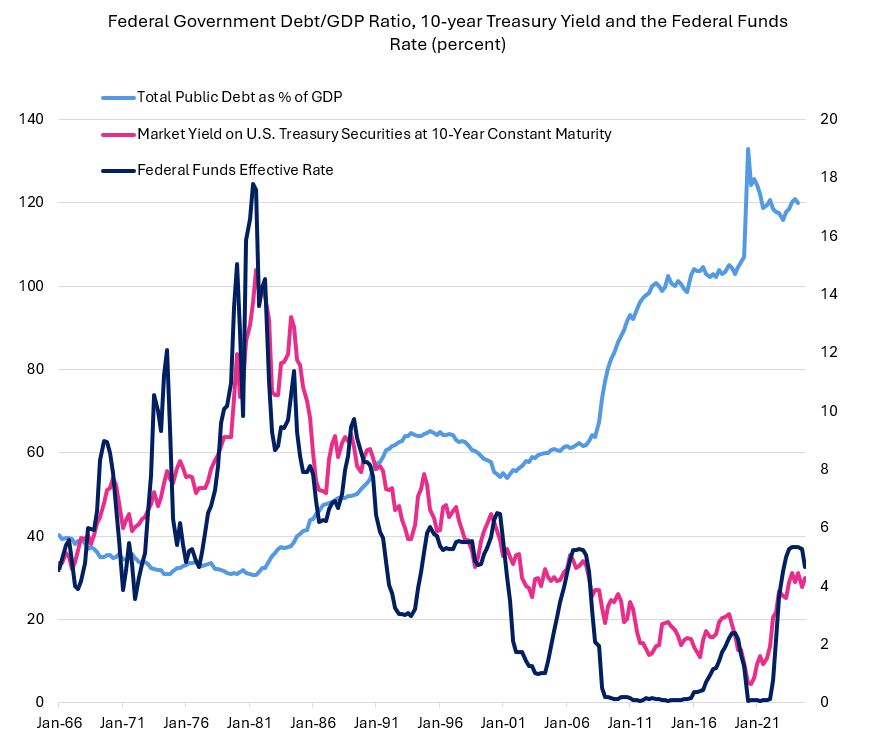

The evidence is overwhelming that growing (or falling) budget deficits do not systematically affect interest rates, nor do changes to the debt ratio. Instead, interest rates on government debt track central bank policy—including the signals central banks send out regarding future policy. Thus, only if central banks make it plausibly clear that they will raise rates if the deficit rises should we expect a rising deficit to be met with rising interest rates. As Figure 1 shows, the 10-year US treasury bond rate closely follows the Fed’s target rate, but—if anything—the correlation with the debt ratio is negative.

FRED Graph Observations | Federal Reserve Economic Data | Economic Research Division, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Source: https://fred.stlouisfed.org

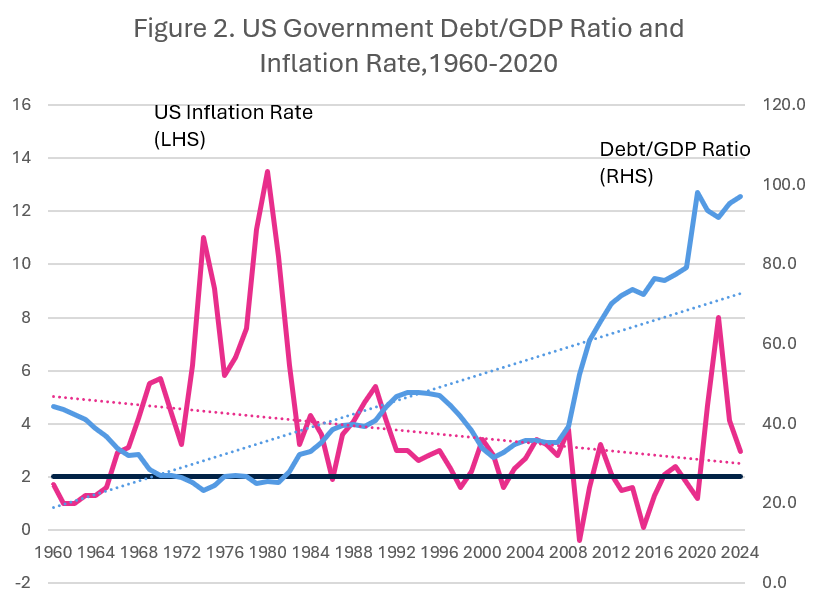

The second claim is that deficits financed by government borrowing generate inflation because the net spending by government increases aggregate demand while the borrowing crowds out private investment, reducing growth on the supply side of the economy. Figure 2 shows that the inflation rate since the end of the 1970s stagflation period had been on a downward trend while the debt ratio grew (except during President Clinton’s second term). Admittedly, these relationships changed during COVID, when inflation, deficits, and interest rates all rose sharply—but policy also changed significantly, first using fiscal policy to fuel recovery and then using tight monetary policy to fight inflation.

CPI for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U), 12-Month Percentage Change

CPI for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U), 12-Month Percentage Change

Given that the conventional views on these relationships do not hold up, it should not come as too much of a surprise that it simply is not true that bigger deficits stunt economic growth. Empirically, there’s no obvious correlation between the deficit ratio and the rate of GDP growth, as Figure 3 demonstrates:

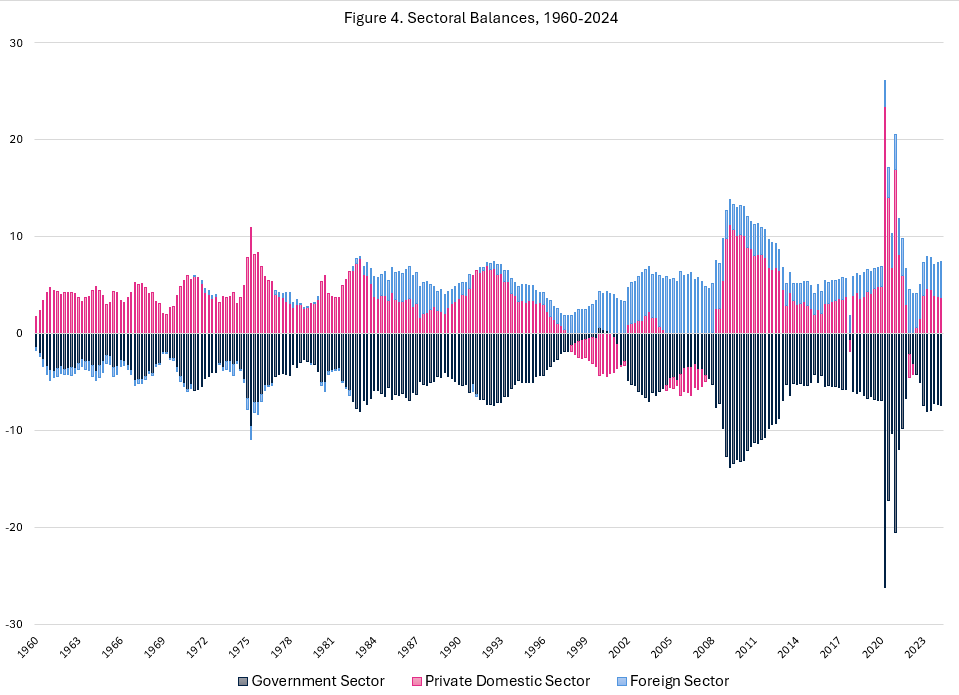

There is, however, one empirical relationship that will always hold—by identity. At the level of the economy as a whole, the sum of the balances across all sectors must equal zero. For every sectoral deficit there must be a surplus: if one sector spends more than its income (a deficit), another must spend less than its income (a surplus). The following graph shows the US private sector balance (households, firms, and not-for-profits), the US government balance (all levels of government, but dominated by the federal government), and the rest of the world’s balance against the US (current account balance).

The foreign sector (blue) has consistently run a surplus against the US (our current account deficit) since the Reagan years—and it tends to grow when the US economy does well (because we purchase more imports). Our government sector is virtually always “in the red” (a deficit—the only visible surplus was during the Clinton administration), while our private sector (pink) is almost always in surplus (“saving” by spending less than income), except in the Dot.com bubble of the late 1990s and again during the housing bubble of the early 2000s.

It is no coincidence that achievement of a budget surplus in the late 1990s occurred when the private sector ran an unprecedented deficit. This could have been avoided only if the US had run a sufficiently big current account surplus to offset the movement of the government’s budget from a deficit toward a surplus. Given the rest of the world’s desire to accumulate dollars by running current account surpluses, and given the normal surplus run by our private sector, the government sector will normally be in deficit. To run a balanced budget, either our private sector would have to reduce its savings (and perhaps run deficits) or foreigners would have to reduce their surplus in trade with the US (or run a deficit in trade).

We will examine in more detail the implications of the chronic US current account deficits in the next section.

The Upside of Exorbitant Privilege

Eichengreen (mentioned above) has long argued that the US enjoys an exorbitant privilege because it issues the primary international reserve currency. This allows the US to pay for its imports using its own currency—it doesn’t need to exchange dollars for other currency, nor borrow other currency to pay for imports. Further, other nations want to accumulate dollars to be used in foreign trade, and as well to defend their own currency from speculative attacks. (Some even peg to the dollar, so must exchange to the dollar on demand.) The rest of the world’s stake in the dollar is huge. As Matthew Klein reports:

About 60% of the world’s foreign exchange reserves are held in U.S. dollars, about 80% of all cross-border trade (outside of Europe) is invoiced in U.S. dollars, about 60% of international and foreign currency banking assets and liabilities are denominated in U.S. dollars, and about 70% of foreign currency debts issued by companies is denominated in U.S. dollars. For perspective, the U.S. economy is worth only about 25% of the world economy. And at least 40% of the physical U.S. dollars in circulation by value, worth more than $1 trillion, are held outside the United States!

To be sure, a century ago, the UK could have boasted about the privilege it enjoyed due to the pound’s dominance, even though the US economy was larger—just as China’s economy has surpassed that of the US (by some measures). There is no guarantee that the dollar will always be top dog. Can—and should—the US keep the dollar on top?

As Minsky argued, it is the responsibility of the issuer of the world’s reserve currency to keep it strong. He likened this to a bank’s responsibility with respect to its own money: holders want to be assured that the money will hold its value.[13] In the case of the dollar, the most important consideration is its exchange rate: will the dollar hold its value against the other main currencies? This is a double-edged sword—the strong dollar keeps imports cheap for Americans and US exports expensive for foreigners, as we will discuss.

Some analysts—including the ratings agencies—also focus on inflation: will the US keep inflation low to preserve the purchasing power of the dollar? This is more complicated because the source of inflation can be domestic or foreign (or both). As a net importer, the US is exposed to inflation of the prices of its imports—with oil and food typically being the most important sources of inflation pressure.[14] Other than by maintaining a strong dollar, the US cannot do much about that (at least in the short run—in the long run the US can increase production of energy and food). Other countries—and their currencies—are also exposed to prices of globally traded energy and food. While oil exporters are benefited by rising oil prices, the trade is in dollars so the higher price is partially offset by a reduced purchasing power of the dollar with respect to their imports.

The other main source of inflation in the US is the shelter component[15]—a complexly determined “price”—that has little direct impact on foreigners, so should not impact willingness to hold dollars. Finally, the vast majority of “dollars” outside the US are not held as stored purchasing power—but rather as financial assets either to provide a return, or to protect exchange rates. For these reasons, it is unlikely that inflation (or its potential) has much to do with the net desire for dollars—unless it affects exchange rates.[16]

What is the nature of the supposed exorbitant privilege provided by the dollar? In addition to cheap imports, it is argued that the US enjoys low interest rates.[17] Typically, it is believed that the US interest rate sets a hurdle that other central banks must beat to attract holders of assets denominated in their currencies. This is because the dollar is a safer currency, always in demand around the world. Dollar assets, in turn, are safer—default by government is unlikely, and the US government (mostly the Fed) is seen as backing up many of the privately issued dollar debts. There are other reasons for trusting in Uncle Sam’s currency related to political and military ties. Hence, interest rates on dollar assets are lower than those in most countries, and when the Fed raises rates, many other central banks follow suit to avoid movement out of their currency-denominated assets (that would lower their exchange rate). However, we do often see bigger countries going their separate ways, setting rates lower than the Fed’s. Still, even though the US is the biggest debtor country in the world, it’s total interest spending on its dollar debts is less than its earnings on foreign assets held by Americans. Overall, the US does enjoy lower interest rates and earns more interest from foreigners on financial assets than it pays out to foreigners.

As we saw earlier, the US has had a current account deficit since the Reagan years—often marked as the beginning of Neoliberalism. Industrial productive capacity around the world grew (first in Japan and Germany but spreading throughout Asia and eventually reaching China), with factory output underpricing (and sometimes exceeding the quality of) US manufacturing. The US lost manufacturers and factory jobs. Domestic wages were depressed because of low wage competition from abroad—with inflation-adjusted blue collar wages in the US held essentially constant until COVID. Free trade agreements also reduced tariffs and other kinds of protections for US producers, reaching well beyond manufacturing to include agriculture and some kinds of services.

The US excelled, instead, in finance, tech, social media, and various areas of research. While GDP growth was not spectacular, it paled mostly by comparison with the US “golden age” (or, against China’s growth rate) but on average it was not largely different from growth in other developed, Western countries. However, average growth of output and income in the US obscured the reality that a huge proportion of Americans was left behind as inequality rose at a very fast pace. The gains from growth went increasingly to the very top. They also were increasingly concentrated in a relatively small number of US regions and counties.

As we’ve shown, the political result was that the working class (defined as those who did not attend college) increasingly moved to the right (Tcherneva and Wray 2025). Those political ramifications have been huge. Trump’s tariff policy is exhibit one. The likely end of Neoliberalism is exhibit two. But those topics are beyond our scope.

Exorbitant Privilege and Budget Deficits

We will conclude with a discussion of the link between exorbitant privilege and the persistence of budget deficits—and rising debt.

As we saw above, the US domestic private sector almost always runs a surplus—with the exception of the deficits that helped to bring on collapse of the bubbles that finally generated the Global Financial Crisis. A persistent deficit run by the domestic household sector is not sustainable for a number of reasons. Households generally want to save—for college, for retirement—and while they might spend more than their income for a while, as their debts accumulate and their savings are run down, they cut back on spending. They also face credit constraints, at least partially linked to income and indebtedness—so at some point lenders will curtail lending.

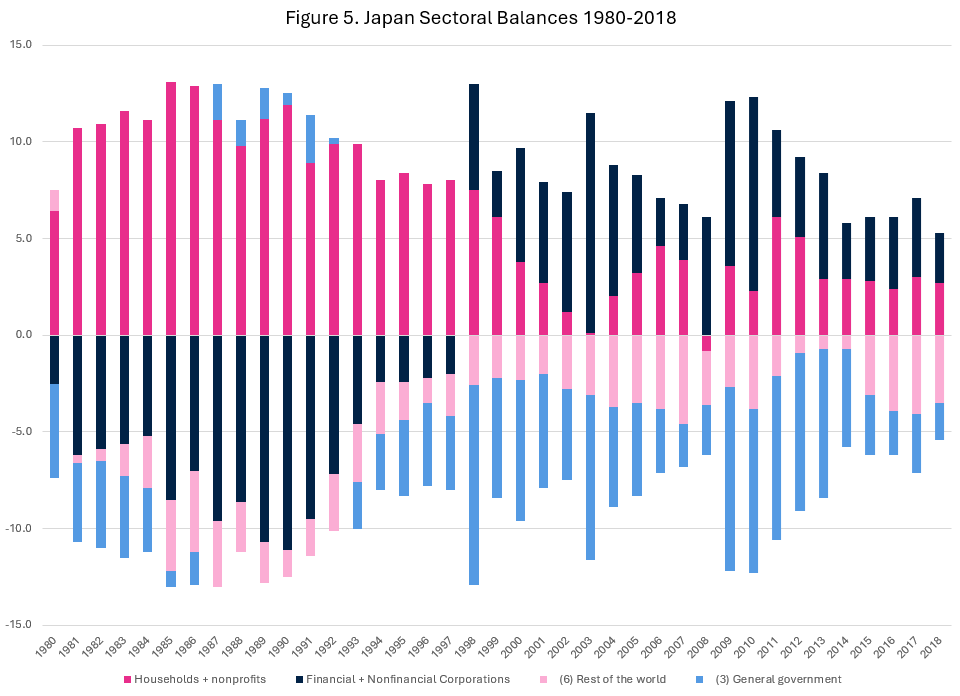

On the other hand, firms can (and in some years do) spend more than their income as they invest in capacity that will increase income later. (Some households can do the same—“investing” in a college education—but household spending is mostly on consumption, not investment.) It is possible that the deficits of firms can more than offset the saving by households so that the domestic private sector runs a deficit—a deficit that is sustainable at least for a while as firms build up capacity. This is what we saw in Japan during its golden age: firms spent more than their income year-after-year from 1980 until near the end of the 1990s, fueling growth. As Figure 5 below shows, this allowed households to save at a high rate (over 10 percent of GDP). Furthermore, Japan ran a current account surplus.

Source: Cabinet Office of Japan

Source: Cabinet Office of Japan

Together the deficit of the business sector plus the deficit of the rest of the world against Japan allowed the government to run a small deficit—and even a surplus in the early 1990s—without harming economic growth. However, at the end of the 1990s the business sector flipped to a surplus, and with less investment and slower economic growth, household saving rates collapsed and the government balance turned to a chronic and generally growing deficit. Later, the Japanese current account surplus also fell due to the Global Financial Crisis, and because of growing competition from lower-cost Asian competitors.

What lessons can we learn from recognition of the sectoral balance identity and from the past 30 years of experience in the US and Japan? While developing Asian countries have managed to achieve very high rates of investment—amounting to a third or more of GDP in some cases—this is exceedingly unlikely for a “consumer-led” developed economy like the US. That means that we are not going to get large enough deficits from the business sector to offset the normal surpluses of the consumption sector—and we rule out persistent deficits of the consumption sector for reasons discussed. Our domestic private sector will normally run surpluses.

As the international reserve currency issuer, the US is not likely to run significant, sustained current account surpluses—in spite of Trump’s imposition of high tariffs and other barriers to trade. The rest of the world wants to accumulate dollars—it is (mostly) selling to the US to get the dollars, not to obtain US output. The world wants dollar-denominated assets. Trump’s proposed tariffs were originally calculated according to a formula linking the individual country’s tariff to its bilateral trade surplus[18] with the US—meaning that the tariff would fall to zero only if the trade was balanced.

By implication, Trump’s view is that a country should only earn dollars to purchase US goods. Essentially, this view sees the dollar only as a medium of exchange—a very simplistic Monetarist view of money—and it conflicts with the role the dollar plays as the international reserve currency. Countries that accumulate dollars for other purposes would be punished with tariffs. This creates an incentive to abandon the dollar in international trade and represents a challenge to the supposed exorbitant privilege.

As Minsky argued, the issuer of the reserve currency must keep that currency strong. Trump wants a weaker currency to promote exports but that conflicts with the condition required to maintain the dollar’s position in the currency hierarchy. Furthermore, Trump has generally used performance of the stock market as a barometer of economic performance. His stop-and-go tariff policy has frightened “investors” in US stocks and led to sell-offs. A weaker dollar is not likely to benefit that market. All of this puts additional pressure on the privilege.

Finally, Trump has railed against “Biden’s inflation.” A weaker dollar plus tariffs on imports is likely to spur inflation—which would probably lead to higher interest rate policy by the Fed. None of these outcomes is likely to please the administration.

Finally, Trump—along with most politicians—wants to reduce the deficit. At the same time he wants to extend tax cuts, so deficit reduction falls on the spending side. We will not address the attempts by DOGE to come up with savings, nor speculate on the final outcome of ongoing budget negotiations. However, we assert that, given a private sector surplus and a current account deficit, the government’s balance will be in deficit—by identity—and will remain in deficit most of the time.

The necessity that sectoral balances will balance ensures this result. While the government sector includes state and local governments, those generally cannot run deficits (49 states have constitutions that prohibit deficits, and financial markets will impose discipline on local governments that do not balance their budget)—meaning the Federal deficit must offset the surpluses of the other levels. Blaming Congress for its inability to balance the budget makes no sense unless one can come up with a plausible plan for eliminating saving of dollars by American households and firms and/or by foreigners.

Footnotes

[1] See my analysis of S&P’s downgrade here: “The S&P Downgrade: Much Ado about Nothing Because a Sovereign Government Cannot go Bankrupt”

[2] “U.S. Downgraded by Moody’s as Trump Pushes Costly Tax Cuts,” Romm, Duehren, and Rennison (2025).

[3] www.mizuho-sc.com/english/ebond/reports/mi010910.html

[4] www.cipe.org/ert/e15/across.php3

[5] “Downgrading Japan,” L. Randall Wray (2002)

[6] There may have been missed payments for technical reasons. For example, in spring of 1979 the US Treasury delayed payment on some Treasury bills that came due, blaming bookkeeping errors and computer problems. “When Did The U.S. Last Default On Treasury Bonds?”

[7] “Ignore the Raters,” L. Randall Wray

[8] Anati R. Admat also contributed a piece, focused on the stock market.

[9] “Ignore the Raters,” L. Randall Wray

[10] The S&P Downgrade: Much Ado about Nothing Because a Sovereign Government Cannot go Bankrupt

[11] For an early, detailed, discussion of the financial practices—including the role of securitization—that led up to the financial crash, see my 2007 piece: Lessons from the Subprime Meltdown

[12] John Maynard Keynes, Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren.

[13] Before the creation of the Fed in 1913 (and the creation of a backstop by the FDIC in 1933), a bank’s deposits could—and often did—fall below par against currency and the deposits of other banks.

[14] See Flying Blind, and for an update, Still Flying Blind after All These Years. In recent years, the US has become a net exporter of oil, and it has long been an exporter of food, so as prices rise, importers need to obtain more dollars to purchase from the US.

[15] Ibid.

[16] While monetarists do take a monetary approach to exchange rates—suggesting that “too much money” causes inflation and exchange rate depreciation—it does not hold up to scrutiny, either theoretically or empirically.

[17] See Klein, cited above:” The supposed “exorbitant privilege” is that Americans are able to borrow much more—at relatively lower interest rates and relatively higher exchange rates—than would be expected given fundamentals.”

[18] Note that the original formula only included trade in goods—services were excluded. The US has a surplus in services.

1 Randall-ek beti Modern Money Theory idatzi duen bitartean, Bill eta Warren-ek beti Modern Monetary Theory idatzi dute. Hirurok MTM delakoaren fundatzaileak dira.

2 Amerikar trilioi bat = europar bilioi bat.

3 https://twitter.com/LHSummers/status/1490424193611141121. Accessed 5 November 2022.

4 Jason Furman: https://twitter.com/jasonfurman/status/1083394281547722752 . The New York Times article also stated, “’M.M.T. was already pretty marginal,’ said Jason Furman, a Harvard economist, noting that, in his view, most policymakers and prominent academics ignored it already.” (Accessed 5 November 2022.)

6 As Saffra put it.

7 Jadanik aipatua, goian: “…The right question is, ‘What do the

American people need us to do?’ […] Once you answered that, then you say, ‘How do you

resource that need?’”

He went on to argue that, as the US government issues its own currency, finance is never the

problem. What matters is resource availability.