The US dollar is losing importance in the global economy – but there is really nothing to see in that fact

(https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=62619)

June 16, 2025

Since we began the Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) project in the mid-1990s, many people have asserted (wrongly) that the analysis we developed only applies to the US because it is considered to be the reserve currency. That status, the story goes, means that it can run fiscal deficits with relative impunity because the rest of the world clamours for the currency, which means it can always, in the language of the story, ‘fund’ its deficits. The corollary is that other countries cannot enjoy this fiscal freedom because the bond markets will eventually stop funding the government deficits if they get ‘out of hand’. All of this is, of course, fiction. Recently, though, the US exchange rate has fallen to its lowest level in three years following the Trump chaos and there are various commentators predicting that the reserve status is under threat. Unlike previous periods of global uncertainty when investors increase their demand for US government debt instruments, the current period has been marked by a significant US Treasury bond liquidation (particularly longer-term assets) as the ‘Trump’ effect leads to irrational beliefs that the US government might default. This has also led to claims that the dominance of the US dollar in global trade and financial transactions is under threat. There are also claims the US government will find it increasingly difficult to ‘fund’ itself. The reality is different on all counts.

All central banks hold reserve currencies which allow them to make foreign exchange transactions that influence the movement of exchange rates.

Under the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates, the capacity of a central bank to defend its currency against depreciating forces depended on the quantity of foreign reserves it held.

That proved to be a major shortfall of the system and ultimately led to its demise.

If a central bank did not have sufficient quantities of foreign currency reserves then it had to seek loans from the IMF under that system and/or devalue its currency under the Bretton Woods protocols.

With the flexible exchange rate system now dominating, central banks still maintain foreign currency reserves for a range of transactions including the smoothing out of major currency movements.

The US dollar is the dominant reserve currency and nations hold reserves of that currency to allow them to transact in trade given that a significant proportion of global commodity trade is denominated in the US dollar.

Having stores of US dollars means a nation does not have to sell its own currency for the US dollar in order to transact in global markets, which provides a modicum of stability to its own currency.

The IMF publishes a dataset – Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER) – which allows us to trace movements in the denomination of currencies held in reserve by central banks.

There are some technicalities – such as the difference between allocated versus unallocated reserves – that we don’t have to go into here.

This data is also relevant to a recently released a report from the European Central Bank (June 11, 2025) – The international role of the euro – along with a detailed – Statistical Annex – which traces the “international role of the euro”.

Any hint that the euro would become a dominant global currency is not supported by the data, which shows that the:

… share of the euro across various indicators of international currency use has been largely unchanged, at around 19%, since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The euro continued to hold its position as the second most important currency globally.

While the “share of the US dollar” in “global official foreign reserves … declined by 2 percentage points at constant exchange rates, to 57.8%” in 2024, the longer term trends have seen the US dollar’s share decline by around 11 percentage points over the last decade.

In the March-quarter 1999, the US dollar share was 71.2 per cent.

By the December-quarter 2024, it had dropped to 57.8 per cent.

For other currencies (the IMF did not start collecting this data for all countries at the same time):

1. Euro – 18.1 per cent March-quarter 1999; 19.8 per cent December-quarter 2024.

2. Pound sterling – 2.7 per cent March-quarter 1999; 4.7 per cent December-quarter 2024.

3. Yen – 17.6 per cent March-quarter 1999; 19.8 per cent December-quarter 2024.

4. Yuan – 1.1 per cent December-quarter 2016; 2.2 per cent December-quarter 2024.

5. Canadian dollar – 1.4 per cent December-quarter 2012; 2.8 per cent December-quarter 2024.

6. Australian dollar – 1.5 per cent December-quarter 2012; 2.1 per cent December-quarter 2024.

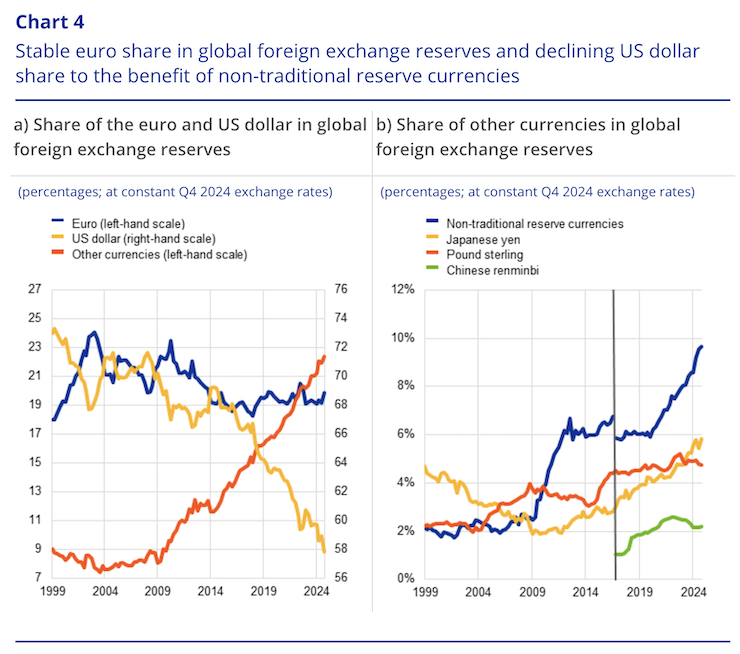

The ECB provide the following graph which shows the shares of various currencies in global foreign exchange reserves.

Being careful not to be confused by the use of the right- and left-hand scales, it is clear that the US dollar has slipped quite substantially and the “other currencies” have increased their importance among institutions that hold foreign exchange reserves.

The “other currencies” include “the Canadian dollar, the Australian dollar, the Korean won, the Singapore dollar, the Swedish krona, the Norwegian krone, the Danish krone and the Swiss franc in decreasing order of estimated importance”.

In terms of the right-hand panel in the graph above, the ECB note that “By the end of 2024 the share of currencies other than the US dollar and the euro had risen to 22.4%, driven by strong gains in non-traditional reserve currencies … its combined share grow by 1.1 percentage points in 2024, to 9.6%.”

Of interest is the fact that the Chinese yuan (renminbi) initially was seen as an attractive reserve currency, its share peaking in 2022.

It has since declined and the most recent report from OMFIF – Global Public Investor 2024 – which studies “global policy and investment themes relating to central banks, sovereign funds, pension funds, regulators and treasuries”, found that:

… Appetite for renminbi has soured. Nearly 12% of reserve managers are looking to decrease holdings in the next 12-24 months.

Why?

This is partly due to relative pessimism on the near-term economic outlook in China, but the vast majority also mentioned market transparency (73%) and geopolitics (70%) as deterrents to investing in Chinese financial assets.

However, the longer-term trends are different.

The survey data shows that:

… over a longer horizon, central banks expect to diversify towards the renminbi. In net terms, 20% anticipate adding to their renminbi holdings over the next 10 years, which is greater than for any other currency. On average, respondents anticipate that its share in global reserves will more than double to 5.6% in the next decade, from 2.3% now.

But that will still not make it a dominant currency.

For both the euro and the renminbi, the global roles played by these currencies continues to be way under the size of the respective economies, which gives people licence to suggest that they will increase their role in global reserves significantly over the next several years.

There is some opinion that Trump’s behaviour will accelerate the trend away from the US dollar.

ECB boss ‘Madame Lagarde’ introduced the ECB Report saying:

… further shifts may be underway in the landscape of international currencies. The tariffs imposed by the US Administration have led to highly unusual cross-asset correlations. This could strengthen the global role of the euro and underscores the importance for European policymakers of creating the necessary conditions for this to occur. The number one priority must be advancing the savings and investment union to fully leverage European financial markets. Eliminating barriers within the EU is essential to enhancing the depth and liquidity of euro funding markets, which is a precondition for a wider use of the euro. The planned issuance of bonds at the EU level – as Europe takes charge of its own defence – could make an important contribution to achieving these objectives.

Note first, that the role of the euro in global foreign exchange reserves has been invariant to the Russian invasion of the Ukraine, which some found surprising.

Lagarde is obviously trying to condition the political debate in Europe in relation to the current arms’ race intentions.

But as I discussed in the recent blog posts – The arms race again – Part 1 (June 11, 2025) – and – The arms race again – Part 2 (June 12, 2025) – the European Commission’s strategy is to sheet the increased debt onto the Member States, which will not turn out to be a successful strategy and may actually lead to a reversal of any sentiment gains with respect to the euro as a reserve currency.

Two factors which can influence the demand by institutions for a particular currency as a reserve are: (a) exchange rate fluctuations, and (b) changing bond yields across nations. The second factor is less of a factor because yields tend to move in concert with economic fluctuations.

However, in relation to the first influence, an IMF report analysing the COFER data (May 5, 2021) – US Dollar Share of Global Foreign Exchange Reserves Drops to 25-Year Low – found that fluctuation in the US dollar since 1999 explains “80 per cent of the short-term (quarterly) variance in the US dollar’s share of global reserves” and the “remaining 20 percent of the short-term variance can be explained mainly by active buying and selling decisions of central banks to support their own currencies”.

Yet, the size of the US bond market coupled with the lack of a significant, risk-free euro bond market means that the US dollar will remain dominant.

The Europeans may long for the euro to become a dominant currency but the nature of the monetary architecture and the obsession with pushing responsibility for debt-issuance on Member State governments and an aversion to issuing EU-level debt backed by the ECB makes it hard for them to achieve their goals.

The hope for the Europeans is that the Trump-induced chaos will compromise the so-called ‘safe haven’ status of the US dollar.

The recent slide in the US dollar exchange rate will see a further decline in the share of the US dollar in global reserve balances.

But the question is whether the tariff hoopla and the rest of the ‘failed state’ meanderings of Trump and his cronies is going to cause a structural decline in the US dollar.

Note: US Border Control officials – I am not planning any trips to the US in the near future!

There is some evidence to support the case that times have changed.

As I noted above, when global uncertainty increases the demand for US-dollar assets (such as government bonds) increase.

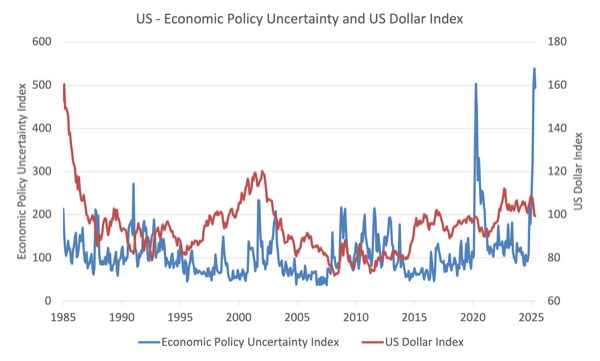

This graph compares movements in the monthly US Dollar Index (DX-Y.NYB) with the – US Economic Policy Uncertainty Index from January 1985 to May 2025.

Prior to 2025, there is a fairly well defined positive relationship between the two – when uncertainty rises, the dollar index rises (the exception being the lagged effect in the early COVID-19 period).

However, in the recent period, that relationship has changed and the Trump uncertainty spike is beyond even the COVID-19 shock and the US dollar index is starting to fall.

These findings are supported by more formal econometric analysis – HERE.

The EPU Index is not available for June 2025 as yet, but the US dollar index continues to fall into June – 2.5 points around since end of May.

The final point today is about what this means for US fiscal policy viability.

One of the accompanying narratives of the declining share of the US in global reserve balances is that the American government will start to struggle to ‘fund’ its fiscal deficit.

These claims which are being regularly rehearsed in the media these days are without foundation.

As regular readers will appreciate, the US government ‘funds’ its deficit in the act of spending, because it is the currency issuer.

No amount of accounting structures that are put in place can change that fact.

When the government instructs its financial agency to credit a bank account to facilitate procurement requirements the number so typed is ‘funded’ at that point.

The number doesn’t reflect taxes or bond issuing revenue.

Those numbers are, in this context, just artefacts of the accounting systems that the government uses to pretend they are ‘spending’ taxpayers or investor funds.

That is not to say that private US traders etc will not be hurt by the sliding importance of the US dollar in global markets.

They enjoy benefits such as an absence of hedging insurance outlays on transactions denominated in US dollars.

Conclusion

But the latest IMF and ECB data and analysis does not suggest these advantages are about to dissipate any time soon, even with Trump going crazy.

And on the claim that MMT is only applicable to the US because of its dominant status as a reserve currency – I discussed that proposition in this blog post – Another fictional characterisation of MMT finishes in total confusion (March 13, 2019).

oooooo

@tobararbulu # mmt@tobararbulu

Another fictional characterisation of MMT finishes in total confusion

(https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=41789)

March 13, 2019

(…). I will soon be back home in Australia and have received a lot of E-mails about the way the Australian media has been treating the recent upsurge in attention about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). The short description is appalling – one-sided, no balance and hardly about MMT at all, despite dismissing our work as garbage. So par for the course really. While most of the articles have just been syndicated hashes of the foreign criticisms that have been published elsewhere from Krugman, Rogoff, Summers and others. But there was one article by a local journalist who tried to predict which side of history would end up looking good in all this and chose, wrongly I think, to throw his cap in with the New Keynesians. More alarmingly though is that this local effort clearly followed the international trend by setting out a fiction and then tearing into that fiction claiming to his readers that this was about MMT. He missed the mark and ended up totally confusing himself. So par for the course.

Remember back to August 2008, when the world was going into financial collapse that none of the New Keynesian macroeconmists saw coming – nor could have seen, given they didn’t even have a financial sector in their theoretical framework – Blanchard wrote his smug article – The State of Macro – which attempted to summarise the consensus that mainstream macroeconomists had reached on how to do economics.

The article would have been written before the worst of the GFC was revealing itself and tells you how removed the mainstream profession had become from reality.

The mainstream has evolved into following a standardised approach to the discipline. All those who sought to publish in the discipline had to follow that approach in order to engage and be successful. Variation was discouraged.

Blanchard wrote glowingly, that macroeconomic analysis had become an exercise in following:

… strict, haiku-like, rules … [the economics papers] … look very similar to each other in structure, and very different from the way they did thirty years ago …

Graduate students are trained to follow these ‘haiku-like’ rules, that govern an economics paper’s chance of publication success.

So if an article submission does not conform to this haiku-like structure it has a significantly diminished chance of publication.

You just have to see the calls by the current critics for a ‘formal model of MMT’ within the Aggregate Demand/Supply, IS-LM framework to see how cloistered (claustrophobic) their approach has become.

The reality is that the mainstream follow a formulaic approach to publications in macroeconomics that goes something like this:

- Assert without foundation – so-called micro-foundations – rationality, maximisation, rational expectations – imposed assumptions about human behaviour that no sociologist or psychologist would remotely recognise.

- These foundations cannot deal with real world people so assume there is just one infinitely-lived agent!

- Assert efficient, competitive markets as the optimality benchmark against which all other states will be assessed – in other words, abstract from the reality of existence.

- Write some trivial mathematical equations and solve – professional mathematicians shrink with embarrassment when they see the naive formality that economists think is state of art.

- Policy shock the optimal ‘solution’ to ‘prove’, for example, that fiscal policy is inneffective (Ricardian equivalence) and austerity is good. Perhaps allow some short-run stimulus effect.

- Get some data but realise poor fit – add some ad hoc lags (price stickiness etc) to improve ‘fit’ but end up with identical long-term results – of course, once you add these ad hoc lags the ‘micro founded’ framework, which is the ‘authority’ that is used to claim ‘scientific’ standing is abandoned.

- Irrespective of that abandonment, maintain pretense that micro-foundations are intact – after all it is the only claim to intellectual authority that these mainstream economists have – which is no claim at all in reality.

- Publish articles that reinforce starting assumptions.

- Get appointments, promotion

- Write commissioned reports (with fees and sponsors largely undisclosed) about how stable the financial sector etc is – parade the reports as independent academic research – and demand more deregulation, cutting of income support systems etc under the guise of ‘structural reform’.

- Knowledge quotient of all this – ZERO – GIGO.

And, on the side, they write ridiculous attacks claiming to be about MMT, when people start questioning the relevance and validity of their work.

And, they have an army of graduate student trolls who Tweet their heads off attacking MMT so they will look good in the face of the ‘high priests’.

It is highly unlikely any of them have read much of the primary MMT academic literature at all.

That is where the struggle of the competing paradigms is at.

The ‘haiku’ stuff was back in 2008.

Then go forward to October 2012, when Blanchard was forced to admit that the IMF had grossly erred in its modelling that was used to construct the Troika’s Greek bailout austerity package.

The policies that were imposed were disastrous, as any MMT economist (including myself) who offered predictions at the time, said they would be.

And then we learned of the mistake.

I wrote about that pathetic back down – which cost hundreds of thousands of Greek workers their jobs in Greece – in these blog posts:

1. So who is going to answer for their culpability? (October 12, 2012).

2. Governments that deliberately undermine their economies (November 19, 2012).

3. The culpability lies elsewhere … always! (January 7, 2013).

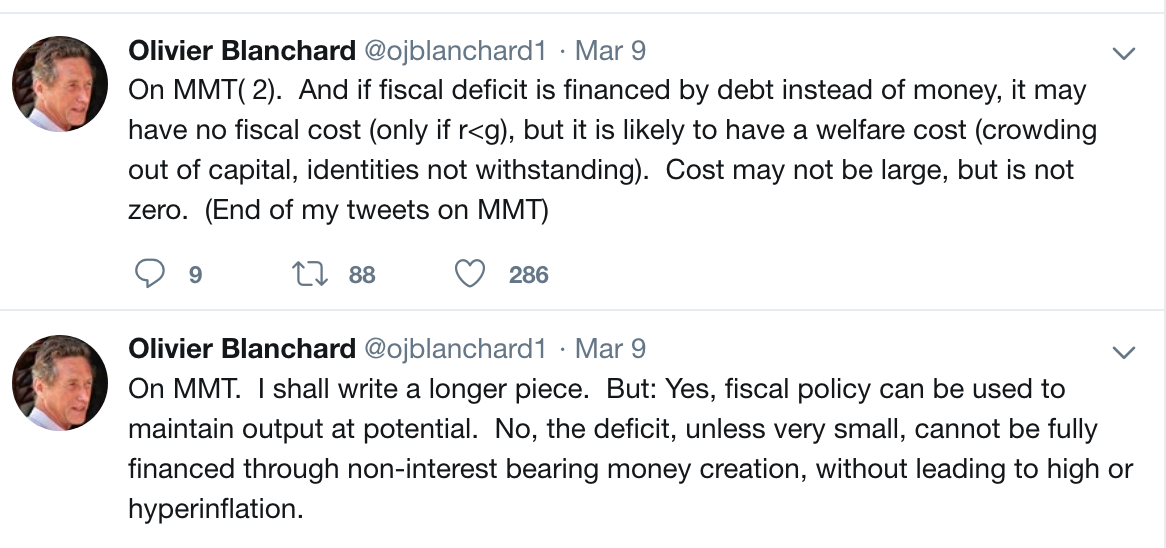

And now Blanchard is Tweeting that like Paul, Ken, Larry and all the rest of the buffoons, he has something deep and meaningful to say about MMT but that we will have to wait with baited breath before he deigns to write it.

For now we should be consoled with these insights – crowding out, hyperinflation. Same old. Been there done that.

The longer piece will just elaborate on that. Nothing new. No engagement. Ignore.

What these guys (and they are all men so far) don’t seem to realise is that we have been working on this stuff for 25 years now and have PhDs just like them and know their stuff like the backs of our hands.

I also liked the pithy analysis of the hypocrisy of the “high priests” of mainstream macroeconomics by Lars Syll (March 10, 2019) – Summers shameless assault on MMT.

These assaults on MMT reflect the circling of the wagons – they will attempt to protect their own place in history by whatever means they can.

But I think, ultimately, they will be found on the wrong side of history, where they have been for decades but no one really directly and comprehensively challenged them about that until MMT came along.

The Australian media has been giving air to all these criticisms via syndication. So in the last few weeks, Australian readers of the major dailies have awoke to headlines about MMT being rubbish, garbage, dangerous etc.

No balance. No attempt to seek critical input.

The media owners clearly just want to push the US line.

And it was only a matter of time before some wannabee local financial journalist would seek to make his/her own mark and summarise the arguments under his own byline.

Last week (March 5, 2019), Fairfax press ran the story – Memo to Bernie and AOC: Debt and deficits still matter – from local journalist Stephen Bartholomeusz.

He is touted by media masthead he works for now as “one of Australia’s most respected business journalists”. His article about MMT would not hold to those standards (even) if they are true.

It looks like he has only read KLOP (Ken, Larry, Olivier and Paul), which sounds like … you know what … and decided to represent them as his own deep analysis.

Not much new in other words and not much indication he has actually read the academic literature from the core MMT group.

His grasp on our work is so tangential that he ends up totally confusing himself as you will see.

He began by quoting from the testimony that the US Federal Reserve Board chairman provided recently to the US Congress:

The idea that deficits don’t matter for countries that can borrow in their own currency, I think, is just wrong …

Powell was answering a question about MMT. His statement indicated that he was not qualified to comment on MMT.

He admitted he hadn’t read any of the literature.

And he will not find it written in any of the core MMT literature that “deficits don’t matter”.

So he must have been talking about something other than MMT, a point that Stephen Bartholomeusz seems to have missed, which is no surprise because by quoting Powell’s ignorance, he disclosed he hadn’t read much either.

But why let you stop making out that you are an expert in these matters?

Stephen Bartholomeusz continued:

The “Green New Deal” and “Medicare for All” programs championed by young Democrats like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AOC) and older ones like Bernie Sanders would see massive increases in US government spending to respond to climate change and economic inequality. The programs have been costed at more than $US90 trillion ($127 trillion).

First, the ‘costing’ at $US90 trillion, whether correct or not, does not lead to the conclusion that the GND would “see massive increases in US government spending”.

There would certainly be increased public spending on GND projects but overall the net spending injection would have to be determined by how much idle capacity was left to be brought into productive use.

At the point where no such idle capacity exists, then the process of trade-offs begins which means spending has to be diverted into GND projects and away from other current uses, whether they be government or non-government.

It might turn out that the so-called (scary) “massive increases” don’t turn out to be all that large at all in absolute terms.

A few paragraphs later, Bartholomeusz shifted, seamlessly, from “massive increases in US government spending” to “a massive increase in government debt and deficits”.

And reminded readers that the US “already has massive debt and deficits”.

What exactly is a massive deficit? According to Bartholomeusz it is one that “is closing in on $US1 trillion a year”.

That would be a large absolute deficit in terms of, say, the Australian economy, but in terms of the scale of the US economy it was recorded at 3.7 per cent of GDP in 2018.

In 2009, it was 9.7 per cent of GDP.

Since 1929, the US fiscal deficit has averaged 3.02 per cent of GDP and has been in deficit 84 per cent of the years to 2018.

Each time it has gone into surplus, a recession has followed soon afterwards.

So a deficit of 3.7 per cent of GDP doesn’t sound massive in that sense.

While a trillion dollars invokes ‘big’, and that is why Bartholomeusz used the absolute figure, no serious economist would make any conclusions based on such a number.

The point is that Bartholomeusz knows his readers will not be discerning enough to scale the deficit appropriately.

Further, even a number like 3.7 per cent of GDP makes no sense in itself.

What is it in relation to? What is the context?

To make sensible assessments about the appropriateness of a particular fiscal position, one has to understand the non-government sector spending and saving position, which includes the external sector.

If the 3.7 per cent deficit was “massive” (meaning in Bartholomeusz-speak inappropriate), and, out of kilter with the spending and saving decisions of the other sectors (private domestic and external), then we should be observing inflationary pressures rising quickly and wages growth escalating in the face of over-full employment.

Neither are happening and are no where near happening.

Mr Bartholomeusz wants to write about MMT but he clearly hasn’t understood the way MMT economists go about analysing a situation.

If he did, he would not have started scaring people with totally over-the-top words such as “massive” in relation to a 3.7 per cent deficit that is supporting a balance sheet restructuring in the non-government sector.

He then tells his readers that:

The core of the MMT concept is that, because the US borrows in its own currency – the world’s reserve currency – it can simply print more dollars to cover its expanding borrowing requirement.

Where exactly did he find that core proposition in the writings of the major MMT developers? He didn’t and should be honest enough to admit he hasn’t read any of it.

He would have found that sort of terminology and construction in the recent KLOP (Ken, Larry, Olivier and Paul) rants.

MMT does not privilege the US because it has a reserve currency.

While it is true that the existence of the US dollar as a desired reserve currency means that they do not have to worry about foreign reserves as much as other nations with less attractive currencies, this doesn’t undermine domestic sovereignty.

Further, MMT economists never talk about ‘printing money’ – because that process doesn’t remotely describe how governments spend their currency into existence.

And, of course, it invokes the scenarios that the conservatives love to invoke of crazed government officials in basements of central banks running printing presses at breakneck speeds to keep up with the hyperinflation.

What MMT tells us is that any currency-issuing government can purchase anything that is for sale in that currency including all idle labour.

It would simply credit relevant bank accounts to make those purchases operational.

What other monetary operations that might accompany that process would depend on institutional arrangements (for example, the government might voluntarily impose a rule on itself to match any spending beyond the numbers it records against a taxation account with some numbers in a debt account and create liabilities accordingly) and political choice.

The operations would not depend on any intrinsic financial constraint.

Mr Bartholomeusz then writes:

Provided the Fed kept US rates below the rate of growth in GDP and the growth in the debt, the US could always service its debts.

This is factually incorrect.

The currency issuer can always service its liabilities as long as they are denominated in the currency that the government issues.

It doesn’t depend on what is happening with the public debt ratio.

He then further demonstrates an unfamiliarity with the core MMT concepts, despite holding himself out as a person qualified to write articles on the topic:

Instead of targeting inflation the goal would be full employment.

MMT is explicit – we propose a macroeconomic framework that allows for full employment and price stability.

And, then, it was bound to happen, the ‘socialist’ scare enters.

Mr Bartholomeusz writes that:

To the extent that inflation did emerge, government policies – targeted taxes and industry policies – would be used to stamp it out, implying a degree of central planning and intervention in the economy that one suspects wouldn’t be easily accepted in the US and which could, by crowding out private sector investment, change the very nature of the US economy.

Well the GND if implemented will “change the very nature of the US economy” and reposition it for a sustainable future.

That much is correct.

But in what way does the normal management of economic policy – tax adjustments, sectoral policies etc – define “central planning”?

Since when has counter-cyclical fiscal policy management become “central planning”?

We lose all meaning in our language if we stretch words and concepts too far.

Further, in what way will the GND lead to the “crowding out private sector investment”?

One would suspect it would crowd in private investment in the new GND sectors.

Where in any GND charter does it say that the non-government sector is prohibited from investing, producing and employing?

And, with the central planning reference as a segue, it doesn’t take long for Mr Bartholomeusz to wheel out the Weimar/Zimbabwe stories, except he hasn’t a clue about what happened in those nations that caused the hyperinflation.

He writes:

History hasn’t been kind to the theory. Germany in the 1920s, Argentina almost routinely and Venezuela more recently are examples of what can happen when governments overdose on debt and lose control of inflation.

Exactly wrong and a violation of the historical record.

Please read my blog post – Zimbabwe for hyperventilators 101 (July 29, 2009) – for more discussion on this point.

A currency-issuing government that increases its spending may increase the risk of inflation, just as any growth in nominal non-government spending might.

If the growth in nominal spending maintains proportionality with the growth in productive capacity then it is unlikely to trigger any demand-pull inflation.

That is irrespective of the monetary operations that might accompany any increase in public spending.

Mr Bartholomeusz clearly doesn’t understand inflationary processes.

Nations can run continuous fiscal deficits forever without “debasing” their currency.

He also becomes very confused.

On the one hand, he claims that the US government will be ‘printing money’ to fund the GND but then writes that MMT “appears to pre-suppose that the rest of the world would keep lending the US money, investing in US Treasuries even as the value of the investments was being devalued by the government printing presses.”

At this point, you realise he hasn’t understood anything.

In his mythical world, with the printing presses running flat chat, why would the government be issuing debt?

Nonsensical confusion.

And finally, the old hoary “MMT can’t work” story, which suggests that MMT is a regime.

Mr Bartholomeusz claims that “without the co-operation of the Fed – MMT can’t work”. Of course, MMT already is working – on a daily basis – in our monetary economies.

It is not a regime we shift to but a framework for understanding how modern monetary systems function – whether the central bank officials know that or not.

Here are some questions for Stephen which the management of the Fairfax media group which pays his salary should force him to answer:

How much of the MMT literature from the core MMT developers have you read Stephen?

How far does your reading go back?

Which peer-reviewed articles and books have you read from the core MMT developers that you can cite as indicating that your representation is ground in the MMT literature?

What qualifications and experience have you got to write such an article?

Conclusion

Australian readers: bug Fairfax and tell them to stop publishing this fake knowledge and deceiving their readers.

They have become nothing better than a snake oil sales company.

oooooo

@tobararbulu # mmt@tobararbulu

There will not be a fiscal crisis in Japan

June 23, 2025

The global financial press think they are finally on a winner (or should that be loser) when it comes to commentary about the Japanese economy. Over the last few years in the Covid-induced inflation, the Japanese inflation rate has now consolidated and it is safe to say that the era of deflation is over. Coupled with the government (and business) goal of driving faster nominal wages growth to provide some real gains to offset the long period of wage stagnation and real wage cuts, it is unlikely that Japan will return to the chronic deflation, which has defined the long period since the asset bubble collapsed in the early 1990s. It thus comes as no surprise that longer-term bond yields have risen somewhat. But apparently this spells major problems for the Japanese government. I disagree and this is why.

Over the weekend, there was an article in The Economist (June 21, 2025, pp.10-11) – Japan’s economy: This time it won’t end well (accessible via library subscription) – which summed up the hysteria that is developing about the recent shifts in the government yield curve.

The Economist notes that:

FOR YEARS Japan was a reassuring example for governments. Even as its net public debt peaked at 162% of GDP in 2020, it suffered no budget crisis. Instead it enjoyed rock-bottom interest rates, including borrowing for 30 years at 0.1%. Now, though, Japan is going from comfort to cautionary tale.

The article then talked about:

1. “Interest payments gobble up a tenth of the central government’s budget.”

2. “The central bank is paying out 0.4% of GDP in interest on the mountains of cash it created during years of monetary stimulus—costs that eventually land on taxpayers.”

3. “Investors are starting to ask if Japan might be vulnerable to a fiscal crisis after all.”

4. “households that will suffer if Japan’s public finances become riskier.”

And so on.

Other articles have talked about a “fiscal cliff” – metaphorically predicting Japan is about to fall off it and face major austerity demands.

The context for all this nonsense is multidimensional.

First, the reference to the central bank “paying out 0.4% of GDP in interest on the mountains of cash it created” relates to the fact that the Bank of Japan now pays a positive interest return on the excess reserves held in the accounts the commercial banks hold at the Bank.

I wrote about why this is a non issue in this blog post – Bank of Japan is making losses on its balance sheet – so what? (July 4, 2025).

If you want to learn about the interest rate support that the Bank of Japan pays on these Current deposit accounts then this page will help – What is the Complementary Deposit Facility?.

Essentially, the Bank of Japan pays the interest rate:

… to financial institutions’ excess reserves (current account balances and special reserve account balances at the Bank in excess of required reserves held by financial institutions subject to the reserve requirement system).

The support rate was first paid during the GFC, when the commercial banks started building up large quantities of excess reserves in the accounts they are required to keep at the central bank.

The scheme evolved from that time into a ‘tiered system’ where some proportion of the reserve balances received the support rate and the rest did not (with some proportion facing penalties) then in March 2024, the Bank decided to pay a positive interest rate on excess reserves.

As I have explained in the past, if there are excess reserves in the cash system and no support rate is paid, the commercial banks will try to rid themselves of the excess in the overnight market – basically lending to banks with a shortage of reserves.

Competition will drive the overnight rate down to zero and if the central bank’s monetary policy target rate is non-zero, then such a process will force it to lose control of its policy target.

So to avoid this possibility, the central banks started to offer a competitive return on the excess reserves held by the commercial banks at the central bank.

The overall support payments reflect the scale of the excess reserves.

The commercial banks have accumulated these excess reserves largely because the Bank of Japan was buying up JGBs in large quantities in the secondary bond markets.

To facilitate these purchases the Bank swaps the bonds for reserves in the commercial banks.

The capacity to make that transaction comes from the fact that the Bank of Japan can always just click a few computer keys to type yen-denominated amounts into the accounts of the commercial banks – ex nihilo.

To suggest that the Current deposits are funding the Bank of Japan is to render the term ‘funding’ meaningless.

In fact, the currency-issuing capacity of the Bank of Japan is what ‘funds’ the excess reserves held at the Bank by the commercial banks (and other financial institutions).

Once you understand that point, then the rest of the propositions advanced in this regard are untenable.

The support rate is currently around 0.1 per cent in line with the recent adjustment in the policy rate that the Bank of Japan announced.

Obviously, if the Bank increases its policy rate in the coming months (as part of its misguided notion of policy normalisation) then the support rate will rise too.

The payment of the support rate is totally voluntary and at the discretion of the Bank of Japan.

The Bank of Japan could simply go back to pre-GFC policy and leave the support rate at zero but that is another story.

If there was ever a hint of financial crisis then the Bank of Japan has all the policy capacity to provide remedies.

A non-issue.

Second, why are the long-term bond yields rising and what does it mean?

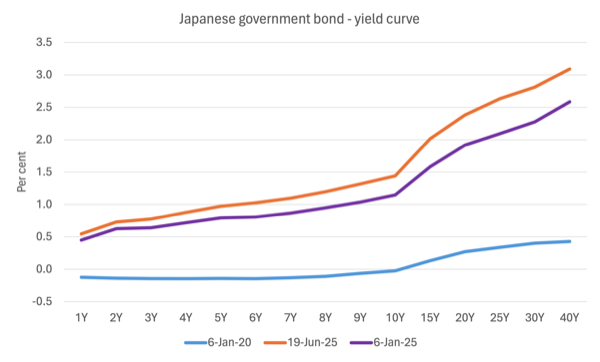

The following graph shows the evolution of the Japanese government yield curve since the onset of the pandemic.

A yield curve simply plots the yields for the different bond maturities (1-year, 2-year etc) that are on issue.

A currency-issuing government could stop issuing debt at any time it wanted and the bond markets would have to create their own benchmark, low-risk asset to replace the risk-free government assets.

Ignoring specific nuances of a particular country, governments match their deficits by issuing public debt. It is a totally voluntary act for a sovereign government.

The debt-issuance is a monetary operation and is entirely unnecessary from an intrinsic perspective.

Governments (more or less) use auction systems to issue the debt. The auction model merely supplies the required volume of government bonds at the price that emerges in the bidding process Typically the value of the bids exceeds by multiples the value of the overall amount the government is seeking.

A primary market is the institutional machinery via which the government sells the bonds. There are, typically, selected financial institutions that participate in the primary issue and ‘make’ the market.

A secondary market is where existing financial assets are traded by interested parties. So the financial assets enter the monetary system via the primary market and are then available for trading in the secondary.

Secondary market trading has no impact at all on the volume of financial assets in the system – it just shuffles the wealth between wealth-holders.

The way the auction works is simple. The government determines when a tender will open and the type of debt instrument to be issued. They thus determine the maturity (how long the bond would exist for), the coupon rate (the interest return on the bond) and the volume (how many bonds).

The issue is then put out for tender and demand relative to the fixed supply in the market determines the final price of the bonds issued.

Imagine a $1000 bond had a coupon of 5 per cent, meaning that you would get $50 dollar per annum until the bond matured at which time you would get $1000 back.

Imagine that the market wanted a yield of 6 per cent to accommodate risk expectations. So for them the bond is unattractive and so they would put in a purchase bid lower than the $1000 to ensure they get the 6 per cent return they sought.

The general rule for fixed-income bonds is that when the prices rise, the yield falls and vice versa.

Thus, the price of a bond can change in the market place according to interest rate fluctuations.

When interest rates rise, the price of previously issued bonds fall because they are less attractive in comparison to the newly issued bonds, which are offering a higher coupon rates (reflecting current interest rates).

When interest rates fall, the price of older bonds increase, becoming more attractive as newly issued bonds offer a lower coupon rate than the older higher coupon rated bonds.

So for new bond issues the government receives the tenders from the bond market traders which are ranked in terms of price (and implied yields desired) and a quantity requested in $ millions.

The government then issues the bonds in highest price bid order until it raises the revenue it seeks. So the first bidder with the highest price (lowest yield) gets what they want (as long as it doesn’t exhaust the whole tender, which is not likely). Then the second bidder (higher yield) and so on.

In this way, if demand for the tender is low, the final yields will be higher and vice versa.

Rising yields on government bonds do not necessarily indicate that the bond markets are sick of government debt levels.

In sovereign nations (not the EMU) it typically either means that the economy is growing strongly and investors are willing to diversify their portfolios into riskier assets.

Or it can mean that that the central bank is pushing up its policy rate and bond yields more or less follow.

The Ministry of Finance publishes – Historical Data of Auction Results – which allow us to see what was going on in the primary market with respect to demand for bonds.

The media is claiming there has been a dramatic drop in demand for Japanese government bonds lately – particularly long-dated issues.

The auction data shows a reduction in demand (hardly dramatic) and the Bid-to-Cover ratios are now around 2.5 to 2.7, which means that there are 2.5 times the bids for the debt than there is debt for sale.

Hardly a disaster!

What determines the slope of the yield curve?

There are various theories about the yield curve and its dynamics. All share some common notions – in particular that the higher is expected inflation the steeper the yield curve will be other things equal.

I outlined these theories in this blog post – Banks gouging super profits, yield curve inversion – nothing good is out there (October 19, 2022).

The basic principle linking the shape of the yield curve to the economy’s prospects is explained as follows.

The short end of the yield curve reflects the interest rate set by the central bank.

The steepness of the yield curve then depends on the yield of the longer-term bonds, which are set by the auction process.

One of the risks in holding a fixed coupon bond with a fixed redemption value is purchasing power risk.

Purchasing power risk is more threatening the longer is the maturity.

So it is one reason why longer maturity rates will be higher. The market yield is equal to the real rate of return required plus compensation for the expected rate of inflation.

If the inflation rate is expected to rise, then market rates will rise to compensate.

In this case, we would expect the yield curve to steepen, given that this effect will impact more significantly on longer maturity bonds than at the short end of the yield curve.

So the basic reason for the shifts in the graph shown above relates to the fact that positive (and relatively stable) inflation is now core in Japan and investors are building that into their expectations and desiring higher yields on long-term assets.

No cause for alarm.

Third, Japan will go to the polls for their Upper House elections next month and the Ishiba government has announced new fiscal measures to ease the cost-of-living pressures (and get votes).

The availability and price of rice has been a contentious issue over the last year or so and the Government is proposing to provide cash grants to households.

The media have dubbed this reckless expenditure.

To put this in perspective adults will receive just ¥20,000 – a pittance.

The Economist thinks that this “is a worrying sign for an indebted country which, like most of the rich world, faces immense fiscal pressure”.

Excuse my laughter.

The Economist also claims that the “Japanese people … would, in all likelihood, have to endure prolonged and destabilising inflation if public debt became unsustainable.”

Of course they don’t exactly state how:

(a) the public debt could become unsustainable given the Japanese government only issues in yen and has infinite (minus one yen) supply of it.

(b) prolonged inflation will result – how? The debt repayments are unlikely to be spent on consumer goods – given the bond holdings represent portfolio decisions about the stock of wealth held in the non-government sector.

So the cash tied up in the bond purchases was not being spent on goods and services anyway.

And even if there was a shift to higher consumption spending that would just reduce the fiscal deficit and the debt-issuance would decline.

In that scenario, one would be hard pressed to say that there productive capacity of the Japanese economy is already exhausted.

If you spend any time in Japan it is apparent that the opposite is the case – there is plenty of spare capacity and there are lots of firms just hanging on to viability with small volumes of sales that could easily scale up quickly.

Fourth, part of the decline in demand for the JGBs is due to the Bank of Japan reducing its purchases of government bonds in the secondary market as part of its ‘normalisation’ strategy.

The primary bond market makers have known for years that they can flip the JGBs they bid for in the secondary market for a profit because the Bank of Japan was buying up big.

But the Bank can easily shift policy again – tomorrow if it wanted to – and increase its demand for the JGBs in the secondary market if it felt that the price of bonds had fallen too far due to lack of private demand.

The Bank can set whatever yield it wants by the volume of its purchases.

Again, a non issue.

Conclusion

There will not be a fiscal crisis in Japan.

oooooo

@tobararbulu # mmt@tobararbulu

The Eurozone Member States are not equivalent to currency-issuing governments in fiscal flexibility

July 7, 2025

I don’t have much time today for writing as I am travelling a lot on my way back from my short working trip to Europe. While I was away I had some excellent conversations with some senior European Commission economists who provided me with the latest Commission thinking on fiscal policy within the Eurozone and the attitude the Commission is taking to the macroeconomic surveillance and enforcement measures. It is a pity that some Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) colleagues didn’t have the same access. If they had they would not keep repeating the myth that for all intents and purposes the 20 Member States are no different to a currency issuing nation. Such a claim lacks an understanding of the institutional realities in Europe and unfortunately serves to give false hope to progressive forces who think that they can reform the dysfunctional architecture and the inbuilt neoliberalism to advance progressive ends. There is nearly zero possibility that such reform will be forthcoming and I despair that so much progressive energy is expended on such a lost cause.

The following claim was rehearsed by two MMT economists in an article they had published in the Review of Political Economy (published February 2024):

… while there was a problem with the original set-up of the Euro system, this has been resolved in the aftermath of the global financial crisis and the more recent COVID pandemic. The Euro area’s institutions allow some flexibility, allowing national governments to act as unconstrained currency issuers in times of crisis1.

In conversations last week with some progressive non EC researchers and academics, I kept hearing the same narrative – ‘the European institutions work’, ‘the fiscal rules are flexible’, etc.

And that came from progressives voices rather than the technocrats in the European Commission, who reliably informed me that they were closing down the flexibility and reinforcing the discipline.

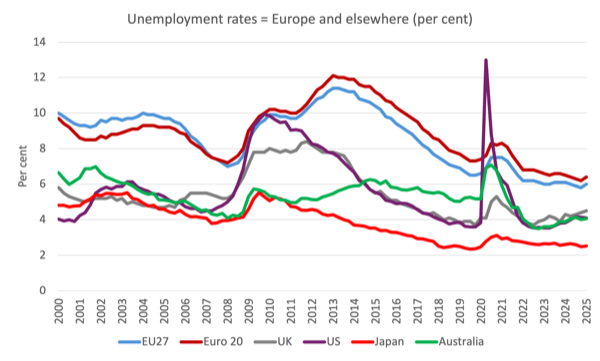

Just to set the scene here is a graph showing the relative unemployment rates for the EU27 countries, Euro20 countries, the UK, US, Japan, and Australia from the first-quarter 2000 to the first-quarter 2025.

The relative performance of the European labour markets is clearly inferior – and there is a reason for that.

The Eurozone Member States, of course, dominate the overall EU27 outcome.

The performance of the individual Member States is also generally poor.

In May 2025 the unemployment rates for 20 Member States of the Eurozone were:

Euro area 6.3 per cent

EU 5.9 per cent

Belgium 6.5 per cent

Croatia 6.1 per cent

Germany 3.7 per cent

Estonia 7.8 per cent

Ireland 4.0 per cent

Greece 7.9 per cent

Spain 10.8 per cent

France 7.1 per cent

Italy 6.5 per cent

Cyprus 3.6 per cent

Latvia 6.9 per cent

Lithuania 6.5 per cent

Luxembourg 6.7 per cent

Malta 2.7 per cent

Netherlands 3.8 per cent

Austria 5.3 per cent

Portugal 6.3 per cent

Slovenia 3.9 per cent

Slovakia 5.3 per cent

Finland 9.0 per cent

These unemployment rates are mostly elevated (by some margin) compared to most currency-issuing countries.

There is a reason for that.

Given time is short today, here is a brief summary of why the claims that the Eurozone Member States now enjoy fiscal flexibility such that they are indistinguishable from currency-issuing countries are unfounded.

First, the 20 Eurozone Member States use a foreign currency – the euro – as a result of surrendering their own capacity when they joined the Economic and Monetary Union.

The currency is issued by the European Central Bank, which is separate from any one Member State (see below).

That means that in order to spend the euro, a Member State government has to first raise taxes.

It also means, more significantly, that if a Member State wants to run a fiscal deficit, then they have to issue debt and rely on the bond investors providing the desired euros at yields that are set by the interests of the investors rather than any notion of population well-being.

Crucially, that debt comes with credit risk and the bond investors know that.

The risk is that the Member State may not be able to generate enough tax revenue to repay the outstanding debt when it matures.

There is no credit risk attached to the debt of Australia, Japan, the US, the UK etc because these governments can always through the monetary machinery of government meet any liabilities that are denominated in their own currency.

Spain, Italy and the rest of the 20 Member States do not enjoy that status.

Which means that the bond markets can ultimately make things difficult for a Eurozone state as we saw during the GFC.

Those who make the claims outlined in the Introduction claim that the ECB has shown its willingness to provide the currency necessary and control bond yields to preclude any insolvency arising.

It is obvious that during the pandemic the fiscal rules defined in the – Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) – were set aside in March 2020 through the activation of the so-called ‘general escape clause’.

There are in fact two clauses:

1. The unusual events clause,

2. The general escape clause.

The European Parliament briefing (March 27, 2020) that was issued when the Commission invoked the escape clause notes that:

In essence, the clauses allow deviation from parts of the Stability and Growth Pact’s preventive or corrective arms, either because an unusual event outside the control of one or more Member States has a major impact on the financial position of the general government, or because the euro area or the Union as a whole faces a severe economic downturn. As the current crisis is outside governments’ control, with a major impact on public finances, the European Commission noted that it could apply the unusual events clause. However, it also noted that the magnitude of the fiscal effort necessary to protect European citizens and businesses from the effects of the pandemic, and to support the economy in the aftermath, requires the use of more far-reaching flexibility under the Pact. For this reason, the Commission has proposed to activate the general escape clause.

Relaxation of the fiscal rules allowed EU member states to increase spending and incur larger deficits to mitigate the economic impact of the pandemic, without immediately facing penalties under the SGP.

Accordingly, for a short period the Member States could run higher fiscal deficits with the knowledge that the bond markets would not drive yields through roof.

Bond investors knew that the ECB would be buying virtually all the debt that was being issued by the individual Member States once it hit the secondary bond market which took all risk of the primary issue away and returned the market makers a tidy little, almost instant capital gain.

Interestingly, in my conversations last week, Commission economists told me they were surprised at how tentative the governments were in taking advantage of this temporary freedom.

Their scrutiny revealed that the policy makers in the Member States understood full well that the special SGP relaxation was temporary and that they anticipated that if they ran their deficits too far beyond the 3 per cent SGP threshold that the subsequent pain that would follow once the Commission resumed the enforcement of the – Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP) – would be difficult to deal with.

Has this ‘freedom’ persisted?

Obviously not.

On March 8, 2023, the Commission released a memo – Fiscal policy guidance for 2024: Promoting debt sustainability and sustainable and inclusive growth – which noted that:

… fiscal policies in 2024 should ensure medium-term debt sustainability and promote sustainable and inclusive growth in all Member States …

The general escape clause of the Stability and Growth Pact, which provides for a temporary deviation from the budgetary requirements that normally apply in the event of a severe economic downturn, will be deactivated at the end of 2023. Moving out of the period during which the general escape clause was in force will see a resumption of quantified and differentiated country-specific recommendations on fiscal policy.

So – Protocol (No 12) – of the Treaty on European Union was back.

The operation of the EDP under – Article 126 – of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union is clear enough.

On July 26, 2024, the European Council, following the EDP rules launched the deficit-based EDP procedure against seven nations (deficits then in brackets):

Italy (-7.4%)

Hungary (-6.7%)

Romania (-6.6%)

France (-5.5%)

Poland (-5.1%)

Malta (-4.9%)

Slovakia (-4.9%)

Belgium (-4.4%)

See Council Press Release for more details – Stability and growth pact: Council launches excessive deficit procedures against seven member states (press release, 26 July 2024)Provision of deficit and debt data for 2024 – first notification – that informs the EDP.

We learned that:

Twelve Member States had deficits equal to or higher than 3% of GDP … Twelve Member States had government debt ratios higher than 60% of GDP …

So there will be more Member States added to those already tied up by the Commission in the EDP and varying austerity timelines will be imposed on them, which will prolong the elevated unemployment levels but also preclude sensible climate policy pursuits.

Further, there is a massive infrastructure deficit (crisis) in Europe as a result of years of austerity which the individual Member States haven’t a hope of addressing given the fiscal straitjacket they operate within is once again being enforced; that makes them vulnerable to domination by bond markets.

Moreover, the Member States are now being bullied by the European Commission (and Donald Trump indirectly) to ramp up military spending and the proposed – Security Action For Europe (SAFE) – under the ReArm Europe Plan will lumber them with more debt and even less fiscal latitude.

Second, no individual Member State in the Eurozone has legislative power to control the central bank – the ECB.

This is a very significant deficiency and we saw just how significant it was when in return for effectively funding the fiscal deficits of the Member States during the successive crises the ECB imposed crippling austerity conditions on the Member States.

The alternative would have been bankruptcy with no legislative recourse other than exit.

Of course, during the GFC, the European Commission feared that if one of the Member States was forced into insolvency because it could not repay outstanding debt upon maturity and/or could not afford the yields demanded by the bond markets for ongoing support as the fiscal deficits started increasing, the whole rotten system would collapse.

That is why they introduced the bond-buying programs.

But it was a political act rather than a progressive show of flexibility.

And we saw exactly what the ECB’s mentality was when the democratic trend in Greece in 2015 was indicating defiance of EC austerity stipulates.

The ECB used the threat of pushing the Greek banking system into insolvency, which led to the democratic will of the people being set aside and the so-called Socialist government turning neoliberal lackey and buckling to the oppression.

No such bullying occurs in nations that have legislative control of their central banks.

Further, the ‘once-size-fits-all’ interest rates spanning 27 economies that are vastly different in the timing and magnitude of their economic cycles means that monetary policy readily provokes economic instability.

We saw that clearly in the period before the GFC, when the ECB lowered rates because Germany and France were in recession (2004).

The lower rates, under other policy settings were inappropriate for the Southern states which were not in recession.

And the deliberate throttling of domestic demand in Germany meant that the growing trade surpluses were invested in property speculations in some of those Southern states, which came unstuck in the GFC.

Third, no individual Member State is able to control the euro exchange rate.

However, the nations with stronger trade fundamentals – meaning with surplus trade accounts – tend to dominate the dynamics of the euro foreign exchange rate and the weaker trading nations then have to accept that parity even if it would be totally at odds with the rate that would prevail if they had their own currencies and individual exchange rates.

This has been a longstanding problem in Europe since the beginning of attempts to integrate significantly different economic structures and cultures, first via the various failed attempts to fix exchange rates within the European community and then, more recently with the common currency experiment.

There is no suitable common exchange rate for the 20 Member States in the Eurozone and those with weaker trade fundamentals continually suffer competitiveness disadvantages that currency-issuing nations with their own flexible exchange rate avoid.

Fourth, those who make the claims in the Introduction then introduce another non sequitur to justify their unjustifiable assertions.

They say, for example, ‘look at the UK, they have crippling fiscal rules too’.

Or, ‘neoliberalism is everywhere’.

It is true that many nations outside Europe have succumbed to the neoliberal ideology and introduce voluntary fiscal rules as a political tool to convince voters that austerity is in their long-term best interests.

But unlike the European situation, these trends reflect the political fashion and can be varied if the fashion changes through a change of government.

In the case of Europe, the Treaties that define the legal framework that the EU operates within have embedded the neoliberalism.

That is, the ideology is embedded with the legal structure of the community that each Member State is beholden too.

That is an entirely different situation.

Article 48 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) defines the process of treaty change.

The process is excessively rigid and no Member State can act alone to alter the rules.

And on matters of substance (which the economic rules surely are) there has to be a consensus of 27 Member States for any part of the Treaty pertaining to those matters to be changed.

The issues where the so-called ‘unanimity rule’ applies and where any Member State has a ‘right of veto’ include fiscal policy, foreign policy, and admitting new countries to the EU.

The short answer is that it would be nigh on impossible to reform the neoliberal economic ideology that is embedded in the legal framework of the EU and which governs the conduct of economic policy.

Currency-issuing countries like Australia might adopt neoliberalism but if it goes too far the government is dumped as we saw in May 2022.

Voters can dump their governments in Europe too but there can be no escape from the neoliberal ideology as long as they remain members of the EU.

Conclusion

I could (and have) written more on this topic.

The problem I see is that real resistance to the capricious and destructive neoliberalism of the EU is compromised by progressives who oppose that destruction but think that better days can be had through Treaty reform.

Even worse are those who mislead by claiming that the Treaties themselves are ‘flexible’ enough to render the neoliberalism optional, which, if true, would see Greece having the same opportunities as say Australia to improve the well-being of its citizens.

It isn’t true.

Can you imagine the Socialist Greek government holding a referendum as it did in 2015 which overwhelmingly voted against austerity then telling the Greek people they were dumb and that the government was going to ignore their wishes, if Greece had its own currency and central bank and the legislative clout choose their own economic course?

I can’t.

1 See https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09538259.2023.2298448

oooooo