Sarrera gisa, Bancor eta Bill Mitchell:

ΛЦƧƬΣЯIƬY IƧ MЦЯDΣЯ@sdgrumbine

An international currency? Hopefully not! – William Mitchell – Modern Monetary Theory

“So what is wrong with the bancor idea? Well, it remains a fixed exchange rate system. Any country that pegs its currency to a foreign currency (or unit that it doesn’t issue under monopoly conditions) immediately imposes constraints on both fiscal and monetary policy, which are not present under flexible exchange rates.”

https://share.google/NIri34ojxTZ30P

Segida

How to break out of the commodification of everything

oo

How to break out of the commodification of everything

July 14, 2025

Regular readers will know that I run a bit, like lots. Last week, while I was in Europe, I decided to stay on Australian time, given the brevity of the mission, so I found myself running at midnight or just after awaking at 22:00 or 23:00 (after going to sleep around 14:00). It turned out to be a good strategy because the abnormally (scary) high temperatures during the day last week in Europe gave way to warm nights with just a hint of crispness in the air – perfect running conditions. Yesterday morning, though, I was in Melbourne, Australia and set off on my early run (around 7:00 being Sunday) and I was a bit tired from yesterday’s Parkrun in Newcastle. Yes, I move around a bit. This morning though, I saw more than the usual numbers out and about on the familiar running areas in the park lands of Melbourne and soon came across Run Melbourne, a large event with screaming speakers, ridiculous geeing-up announcers on microphones, and thousands of people blocking the usual serene early morning paths along the Yarra River. I had earlier been re-reading Chapter 13 of Harry Braverman’s colossal book from 1974 (which everyone should read) – Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century – which was published by Monthly Review Press. The words of – Harry Braverman – came back to me as I tried to work out a way around yesterday morning’s mayhem down by the river.

Further reading

I have written about these themes before and these posts are indicative of many:

1. To reclaim the state, we have to start with ourselves (December 21, 2021).

2. Why progressive values align more closely with our basic needs (January 21, 2019).

3. Neoliberalism corrupts the core of societal values (March 28, 2018).

4. Why Uber is not a progressive development (August 16, 2016).

5. The mass consumption era and the rise of neo-liberalism (January 7, 2016).

6. Self-imposed corporate regulations control workers but choke productivity (October 30, 2014).

7. Bullshit jobs – the essence of capitalist control and realisation (September 5, 2013).

8. Sport and doping – the spreading tentacles of capital (February 11, 2013).

9. We need more artists and fewer entrepreneurs (January 10, 2013).

10. The labour market is not like the market for bananas (August 17, 2012).

Harry Braverman and the spreading profit machine

Harry Braverman died a premature death as a result of cancer in 1976, not long after he published Labor and Monopoly Capital.

It was a great pity because his magnificent legacy to radical research and writing was cut short.

You can see his extant works though on the – Marxists’ Internet Archive: Harry Braverman – starting with his writing as a 20-year old in 1940 up to 1959 (the Archive is incomplete so far).

In the blog posts above, I have covered some of his ideas in more detail.

Harry Braverman examined what he termed his “de-skilling” hypothesis where capital systematically restructured labour processes to enhance their control in order to extract higher profits.

He also proposed that commodification was becoming generalised under Capitalism – extending into more and more areas of our ‘social’ lives.

Progressively, these ‘labour processes’ (market-values) subsume our whole lives – sport, leisure, learning, family – the lot.

Everything becomes a capitalist surplus-creating process.

This process has intensified under neoliberalism – it seeks to commodify everything.

That is create labour processes that produce commodities for profit.

The spread of the labour process is one of the characteristic features of the last several decades.

Even those activities that have previously been part of our non-working lives – our lives away from the oppression of work – are targets for commodification.

If you read Labor and Monopoly Capital, you will find that Braverman tried to reorientate the debate on the Left back to the essence of work and the dynamics of surplus value production as it affected the way people worked and lived.

He was particularly interested in how workplaces were changing as the corporate structures became more concentrated and politically powerful.

This was the beginning of the period when the Left were becoming obsessed with ‘post modernism’ and losing touch with the essence of the Marxist tradition.

So various dead-ends starting emerging – gender, ethnicity, sexuality. Identity politics!

I am not saying these are dead-ends because of their unimportance.

Each of these issues is crucially important.

But as the Left splintered into various groups pursuing one identity issue or another, it lost a central organising focus – the class conflict between labour and capital – within which the pursuit of these identity issues would have been more powerful and effective.

With the two trends – an obsession with ‘individualism’ (breaking down the collective and societal understandings of poverty, unemployment etc) and the broadening of the labour processes – many aspects of our society changed fundamentally.

Harry Braverman wrote (p.14):

And finally, the new wave of radicalism of the 1960s was animated by its own peculiar and in some ways unprecedented concerns. Since the discontents of youth, intellectuals, feminists, ghetto populations, etc., were produced not by the “breakdown” of capitalism but by capitalism functioning at the top of its form, so to speak, working at its most rapid and energetic pace, the focus of rebellion was now somewhat different from that of the past. At least in part, dissatisfaction centered not so much on capitalism’s inability to provide work as on the work it provides, not on the collapse of its productive processes but on the appalling effects of these processes at their most “successful.” It is not that the pressures of poverty, unemployment, and want have been eliminated — far from it — but rather that these have been supplemented by a discontent which cannot be touched by providing more prosperity and jobs because these are the very things that produced this discontent in the first place.

Remember this was written in 1974 and he was commenting on the experience of an evolving full employment situation where workers had jobs but the jobs were being redesigned, restructured – call it how you like – into activities that increasingly alienated the workers and increased the surplus value creation for capital.

So, calling for more jobs might sound like a reasonable thing for a Leftist to advocate but our conception of full employment has to be different now to ensure we are not just satisfied with creating work.

Politicians are wont to tell us how many jobs they are creating as if that is a standard to aspire to.

But what Harry Braverman was telling us way back then was that the way Capitalism was evolving was no way forward if we wanted sustained prosperity for all.

In – Chapter 13 The Universal Market – Harry Braverman begins by noting that the:

The scale of capitalist enterprise, prior to the development of the modern corporation, was limited by both the availability of capital and the management capacities of the capitalist or group of partners.

As a consequence, the scope of capitalist enterprise in our lives, while central to our capacity to obtain wage payments, was somewhat limited.

There were many activities in our daily lives, particularly within the family, that had not yet become ‘labour processes’.

The spreading of the labour process, where increasingly, every hour of every day is ripe for commodification is exactly what Harry Braverman predicted in the early 1970s in ‘Chapter 13 The Universal Market’ of Labor and Monopoly Capital.

He clearly understood that capitalist profit-making would seek to impose its constructs on all aspects of human activity.

Even those activities that were previously part of our non-working lives – our lives away from the oppression of work.

Where we have fun.

The aim of Capital was to make everything ‘work’ by which a special meaning was attached – that activity that allowed private capital to make profits and accumulate more capital.

So activity or effort that helped communities – plant a tree or help an elderly person wash or whatever – was not considered to be work under this spread of labour processes.

Such work was vilified as being unproductive and constituted boondoggling.

That is one of the reasons the elites are so opposed to government direct employment creation.

They are scared that people might challenge the concept of ‘work’ and start realising that effort expended outside of the profit-making machine is, in fact, highly rewarding, if not just because it connects us as humans and rewards our inner needs to be useful to each other and feel good when someone else is feeling good.

If that idea spread then the game would be up for the elites.

We would not keep supplying more effort to private capital at diminishing or flat real wages growth.

We would not tolerate millions of people being unemployed and being used as a rump (a reserve army) to suppress wages growth.

Importantly, we would start to see that governments could use their fiscal powers to create commonwealth rather than private wealth and we would not tolerate corporate welfare at the expense of more general human welfare.

If we judge all human endeavour and activity by whether they are of value in a sense that we judge private profit making then we will limit our potential and our happiness.

So what has this to do with Fun Runs

All this is relevant, I think, to what has happened with community sport and mass participation events.

Sport was once considered to be the antithesis of ‘work’.

It was part of our play to soothe our souls (and bodies) after the hours of working for the boss to generate profits that the corporation would enjoy.

Increasingly, sport is now work – a labour process creating surplus value – albeit as a variation on the normal work process.

Retired Australian Professor of Sport Policy, Bob Stewart, who formerly played for the Melbourne Football Club in Australia’s premier football competition, published a magnificent article in 1980 – The Nature of Sport under Capitalism and its Relationship to the Capitalist Labour Process in the journal Sporting Traditions, 6(1), 43-61]

Bob Stewart traces the characteristics of modern sport that define it as a work place rather than a leisure activity, which is an “activity … performed for its own sake, or as an end in itself”.

An ‘activity performed for its own sake’.

The – Running boom of the 1970s – was a really great movement and:

… The boom was primarily a ‘jogging’ movement in which running was generally limited to personal physical activity and often pursued alone for recreation and fitness …

Growth in jogging began in the late 1960s,[1] building on a post-World War II trend towards non-organized, individualistic, health-oriented physical and recreational activities.

Studies have shown a continuous trend of ‘democratization’ among participants of running events since 1969 with broader socio-demographic representation among participants, including more female finishers …

It was community oriented and brought lots of people into contact with each other, who would normally not interact.

It engendered a sense of self worth and improved the health of participants, notwithstanding the growth in sporting injuries.

But it was also too much fun to be left as it was.

The corporations saw profits in what began as just a grass roots movement.

And soon enough the ‘fun run’ concept emerged and it has intensified since.

Except the fun bit was subjugated for the profit bit.

Now these mass community events are major profit makers for the companies that organise and stage them.

Participants pay enormous entry fees enticed by the chance to receive a plastic finishing token or some other piece of trivia.

High-priced merchandise is flogged to the participants as ‘mementos’ – probably made for a fraction of the retail price.

They also turn people into walking advertising boards for corporations yet the people earn no remuneration.

Cities get closed down at great inconvenience to the public so the corporations can make profit.

The event organisers are crafty and often suggest these are charity events.

The evidence is that most of these events do not contribute a cent to charity – although individual participants might raise money off their own back during the events.

This article – How much of your fun run entry fee goes to charity? – documents research into that question.

I thought the evidence that “the break even point where the fun run costs are covered is roughly 1600-1800 entrants” was interesting even though that threshold was event specific.

The event that crippled inner-city Melbourne yesterday – Run Melbourne – had by their own accounting ‘more than 27,000 runners’.

Run Melbourne, which is representative of these big events, also refuses to disclose its books so we have no idea of how much the event costs to stage and how much profit they take from the $A168 adult fee for the half-marathon, $A95 for the 10k event, and $A69 for the 5.5k event.

They hold out that they have raised lots for charities but this comes via individuals making their own appeals to sponsors to contribute if they finish.

Run Melbourne also note that “No portion of the entry fee will be donated to charity. Entry fees are used to cover the cost of staging the event.”

Yet they will not disclose the break down of costs and profits.

Go figure.

The participants become part of the surplus value producing machine that masquerades as a community event.

And while in other labour processes, workers at least get paid for some of the hours they give to the profit machine, the runners/walkers in these community events pay the organisers so they can be used to make profits.

Which is why I love Parkrun

Parkrun – is the antithesis of this profit-machine that has taken over our leisure and sporting fun.

Every Saturday, runners all over the world, line up at 8:00 (sometimes 9:00) for their weekly 5km run, walk, whatever.

It is organised by volunteers – the revolving group who run most weeks but offer their services occasionally to keep the show running.

There are no entry fees.

All participants are timed and there is an elaborate world-wide database that allows one to track their history.

Some run fast (or try to in my case).

Some walk.

I have done parkruns in the UK, Japan, Netherlands and Australia.

Every time I sense the same spirit which is the antithesis of capitalism.

There is a massive sense of engagement and bonhomie among those who participate.

There is minimal corporate involvement and it is restricted to acknowledging the sponsors at the start of the event.

There is some merchandise available via the home page but all proceeds go back into growing the movement.

It is taking us back to the running boom of the 1970s where the emphasis was on participation, exercise and community.

Conclusion

A bit of a different blog post.

Parkrun is an example of a movement that gives me some hope that we can work ourselves back to a past without labour processes intervening in everything we do.

I see these movements being integral to advancing the bio economy based on localism and community action rather than the prioritisation of private profit.

I will write more about the research I am doing in this area in further posts.

oooooo

ΛЦƧƬΣЯIƬY IƧ MЦЯDΣЯ@sdgrumbine

This is the intergovernmental actions that some folks take super seriously when for the average activist, it is more than enough to understand that the federal government (via law/Art1sec8) creates the dollar and by that same law destroys dollars when received as a tax. Purging reserves is the function within the banking system, but is it really something folks will take and understand? They should, but folks have the attention spans of gnats and are weirdly herd like, going with whatever their buddy at the barstool tells them to think. Pity? Yes. Kinda sad, but what are you gonna do? Force people to think and understand? Kinda tough when they have shutoff their ability to think.

Aipamena

Imports are a Benefit & Exports are a Cost@CarlitosMMT

uzt. 17

The sale of Treasury securities to the Primary Dealers funded by the Fed is an intergovernmental operation to drain checking accounts at the Fed so as to give the govt the means to target a positive own rate. It’s a compositional shift of the net-dollar supply ..

oooooo

Ashish Barua आशिष बरूआ #MMT — INDIA

@barua_ashish

Mainstream economics is designed to protect concentrated economic power and make it easier to exploit the masses, that’s the whole game. That’s why the truth about how a currency-issuing government actually operates is tucked away in obscure corners of public economics or money and banking courses, never front and center.

And after decades of this flawed, manipulative teaching, entire generations have been brainwashed into believing the biggest lie of all, that a government with its own currency operates like a household. It’s economic propaganda, not education. #MMT

Aipamena

ΛЦƧƬΣЯIƬY IƧ MЦЯDΣЯ@sdgrumbine

uzt. 17

This is the intergovernmental actions that some folks take super seriously when for the average activist, it is more than enough to understand that the federal government (via law/Art1sec8) creates the dollar and by that same law destroys dollars when received as a tax. Purging x.com/CarlitosMMT/st… (…)

oooooo

When the Federal Government spends it: Spends new dollars into existence

When the Federal Government taxes it: destroys dollars, more precisely reserves.

It never prints money for the heck of it. It spends on law and policy. So interest rates: new money. Social Security new money.

Taxes, FICA, etc… yep, you guessed it, destroy money. All Federal spending is new money. All Federal taxation is money deletion… (no fucking printing money.)

oooooo

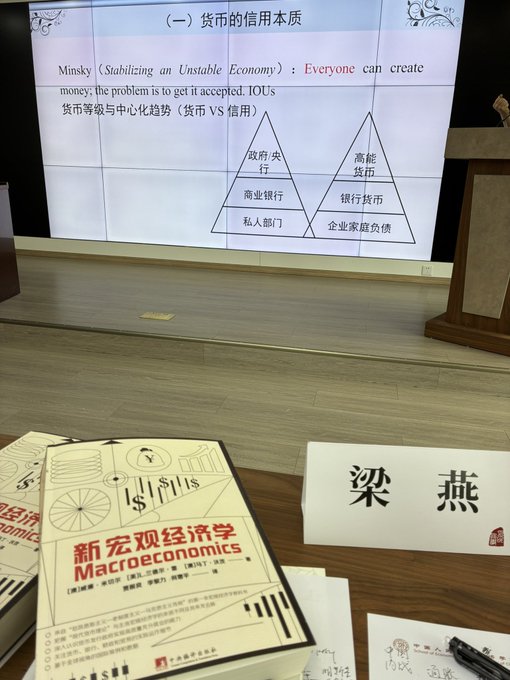

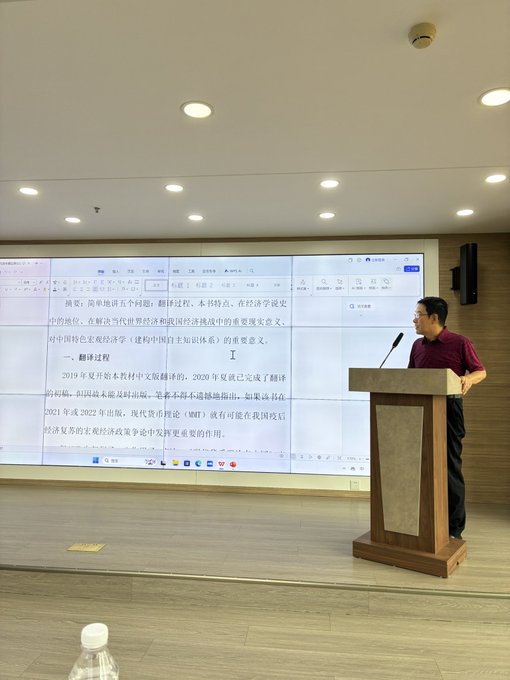

New Macroeconomics – Chinese translation of the MMT macro textbook. Product of years of hard work and a landmark development for MMT in China!

oooooo

What do we do about our $36 Trillion National Debt? On our latest @TheMiddle_Show

episode, economist @StephanieKelton of @stonybrooku says we should stop worrying about it so much.

Bideoa: https://x.com/i/status/1948713892651077772

Full show on the podcast:

oooooo

Before our #MMT workshops, we will be participating in the Modern Money Lab UK Anti-Austerity Conference, with a similar theme – maybe we will see you there.

.(https://modernmoneylab.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Working-Paper-No-8.pdf)

oooooo

Ce blog a pour objet de diffuser les principes de Modern Monetary Theory en promouvant une culture économique qui rejette l’austérité et vise le plein emploi et l’intérêt public.

- Questions et Réponses

- Pour commencer

- Théorie

- Politique économique

- Réalité opérationnelle

- Approfondissement

- Tous les articles

- Vidéos

- Livres

- Fiches conceptuelles

- Articles in English

- Glossaire

- Visualiseur

- Qui sommes-nous

- Contact

The Economy of Narratives

How We Become the Guardians of Our Own Ideological Prison

by

Robert Cauneau

7 August 2025

Introduction

Why is it that visibly false economic analogies, such as that of the state managing its budget « as a responsible father, » dominate public debate with such unwavering force? How can we explain that the anxiety-inducing narrative of the « wall of debt » or the « burden on future generations » continues to justify austerity policies, even though detailed operational analyses, describing the system’s actual « plumbing, » demonstrate its inadequacy? The paradox is not so much that misconceptions persist despite the facts, but that they impose themselves as organized narratives, conveying emotion, legitimacy, and power. These narratives are not intellectual accidents, but cognitive and political instruments, shaped to be believed and to make alternatives unthinkable.

This article advances a simple thesis: the battle for a better understanding of economics is not simply a battle of facts against errors, but a battle of narratives. Technical reality, however rigorous and demonstrable, struggles to assert itself because it clashes with a dominant narrative that is much older, simpler, and, above all, more emotionally powerful. The main challenge for approaches like Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is not to prove its technical coherence—it is—but to overcome its own narrative deficit.

This analysis is an extension of a reflection begun in a first article, entitled « What is Real? How Our Evidence Alienates Us »1. This first part explored the philosophical and sociological foundations of our perception, showing how what we call « reality » is in fact a social construct, shaped by language and habit.

This article constitutes the second part of this two-part series. It moves from the « why » to the « how » and the « who. » From a general analysis of the mechanisms of belief, it shifts to the strategic analysis of a specific information war. It no longer simply asks why our minds are fertile ground for myths, but how this ground is actively cultivated, by whom, and for what purpose.

To do this, our article will be structured in four parts. First, we will dissect the anatomy of the dominant economic narrative. Next, we will expose the counterintuitive monetary reality it seeks to mask. Then, by drawing on Lippmann, Chomsky, and Gramsci, we will analyze the powerful machine that creates and sustains this collective denial. Finally, we will outline ways to construct a counter-narrative, because to replace a powerful story, we must be able to tell a better one.

Part 1: Anatomy of the Dominant Narrative – The Power of Metaphor

The economic discourse that dominates the public sphere is not a collection of neutral facts. It is a narrative construct based on metaphorical foundations deeply rooted in our culture. To understand its power, we must dissect its mechanisms.

1.1 The Household Metaphor: The Power of Personal Experience

The cornerstone of the entire orthodox narrative is the analogy between the state and the household (or business). The state, we are told, must manage its finances « like a good father. » It must « balance its budget, » « not live beyond its means, » and « tighten its belt » in times of crisis. This metaphor is incredibly effective, not because it is true, but because it is intuitive.

Its power rests on three pillars:

The Appeal to Universal Experience: Everyone understands the reality of a family budget. Everyone knows that they cannot spend more than they earn (or borrow) and that debts must be repaid. By reducing the state to this scale, the metaphor makes a complex and abstract subject immediately accessible and understandable. It transforms the citizen into a self-proclaimed expert on public finances, as they project their own experience onto the state.

The Mobilization of a Moral Framework: The household metaphor is not descriptive; it is prescriptive. It does not describe how the state is, but how it should be. It imports into public debate a whole set of moral values associated with domestic management: prudence, responsibility, foresight, and saving. Conversely, a public deficit is immediately equated with recklessness, extravagance, or even a form of immorality (« living off others »).

The Illusion of Symmetry: The metaphor works because it masks a fundamental asymmetry. A household is a user of the national currency; it must earn or borrow it before it can spend it. The state, for its part, is intrinsically the creator of that same currency. The household metaphor denies this essential difference, erases the state’s monopoly on its currency, and presents the latter as one actor among others, subject to the same constraints as those it is supposed to govern.

Ultimately, the household metaphor is a rhetorical tool that achieves the feat of making the false intuitive and the true counterintuitive. It bypasses rational analysis in favor of an emotional and moral reaction, thus creating incredibly fertile ground for austerity policies and the limitation of the state’s role. This is the first and most powerful narrative barrier that must be removed in order to think differently about the economy.

1.2 The Debt-Sin Metaphor: Guilt and Temporal Burden

While the metaphor of housework anchors the debate in the present experience, that of « debt-sin » projects it into the future, burdening it with intense moral guilt. The vocabulary used is never neutral; it is borrowed from the register of fault, burden, and damnation.

We are not talking about « outstanding government securities, » but about the « wall of debt, » an image of impending catastrophe. We are not talking about a financial liability that is the counterpart of an asset, but rather a « burden » that we would bequeath to our children, an original sin for which they would have to pay the price. This rhetoric transforms a simple accounting entry into a moral transgression.

This « debt-as-sin » metaphor draws its power from three sources:

- The Activation of Parental Anxiety: Nothing is more powerful than the call for responsibility toward future generations. By framing public debt as a « burden » for our children and grandchildren, the narrative transforms an economic debate into a question of parental duty. Who would dare, knowingly, « mortgage their children’s future »? This rhetoric is designed to be unstoppable, because violating it is presented as an act of generational selfishness.

- The Confusion Between Public and Private Debt: The narrative exploits our understanding of private debt. For an individual, a debt is a real constraint that diminishes their future freedom and must be repaid through future effort (work). Applying this model to public debt ignores a fundamental accounting truth: at the aggregate level, the « burden » of public debt is exactly equal to the net financial « wealth » of the private sector.

- Resonance with a Judeo-Christian Heritage: The concept of debt is deeply linked, in our culture, to those of sin and guilt. This association is particularly evident in the Lord’s Prayer, where the English versions speak of debts and debtors, while the German uses Schuld, a word that means both moral failing and financial debt. By calling debt a « burden, » it is given a quasi-religious weight. Repayment becomes a form of redemption, and austerity a necessary penance to atone for the sins of past prodigality.

The « debt-sin » metaphor is therefore the moral weapon of the dominant narrative. It paralyzes present action by instilling guilt in the name of a fantasized and poorly understood future. It transforms citizens into sinners and politicians into preachers of fiscal virtue, making any rational discussion about the role of public spending and long-term investment extraordinarily difficult.

1.3 Fertile Ground: When Our Biases Meet Ideology

These powerful metaphors—those of the household and the debt-as-sin—are not mere linguistic errors or innocent pedagogical shortcuts. Together, they form a coherent narrative whose function is not to describe the world, but to silently shape it. It is not imposed by force, but through the spontaneous adherence of those it constrains: this is a form of symbolic violence, in which the categories of perception imposed by the dominant become the common sense of the dominated.

- Legitimizing Austerity and State Withdrawal: By presenting the state as an indebted household on the verge of bankruptcy, the narrative justifies in advance the need for austerity policies. Reducing public spending, cutting public services, or privatizations are no longer presented as questionable political choices, but as inevitable sound management measures, dictated by an implacable accounting « reality. » This is the era of « There Is No Alternative » (TINA): the state must withdraw, not out of ideological choice, but out of financial obligation.

- Depoliticizing Economic Decisions: The dominant narrative aims to remove major economic decisions from the realm of democratic debate and entrust them to supposedly neutral and objective forces: the « markets » and the « experts. » The « financial market » is established as the supreme arbiter of state conduct, distributing good and bad points via interest rates and rating agencies. Any policy that displeases these markets is immediately labeled « unrealistic » or « irresponsible. » The question is no longer « What type of society do we want to build? » but « Are our ambitions compatible with market confidence? »

- Maintaining a Specific Order of Power: Ultimately, this narrative serves to maintain a status quo in which decision-making power is concentrated in the hands of a financial and technocratic elite. By limiting the perceived capacity of the state to intervene in the economy, private actors are given free rein to organize the production and distribution of wealth according to their own interests. Fear of public debt thus becomes a powerful tool of social and political discipline, discouraging any ambitions for profound societal transformation that would require a massive mobilization of resources by public authorities.

The dominant narrative is therefore not just a story we tell ourselves about the economy. It is the story some tell to ensure that the economy operates on their terms. Becoming aware of this is the first step in understanding that the battle for an alternative vision of the economy is, above all, a battle for the right to tell, and to construct, another story.

Part 2: The Counterintuitive « Reality » – The Narrative Challenge of MMT

After dissecting the dominant narrative, which relies on moral metaphors and misleading analogies, it is time to turn to MMT’s description of reality. Before analyzing its narrative challenge, it is essential to emphasize that MMT is not, at its core, another narrative. It is, above all, a rigorous description of the operations and monetary « plumbing » of a modern state.

It starts from an indisputable historical and accounting fact: a state that creates its own currency in a floating exchange rate regime can never involuntarily default on a debt denominated in that same currency. Its capacity to create money to meet its payments is nominally unlimited. This factual solidity is the foundation of the entire analysis.

It is undoubtedly precisely because this foundation is so solid and so different from the usual narrative that MMT hits a wall. The problem is not its truth, but its translation into a comprehensible and acceptable story. It is this paradox, a technically robust but narratively counterintuitive theory, that we will now explore.

2.1 The « Real » of MMT: An Inversion of Causal Logic

The « real » described by MMT is not a theory of what the economy should be, but a description of what it is. It is based on a complete inversion of the causal logic traditionally taught.

- Spending Precedes Revenue: Unlike the household, the state does not first collect money to spend it. It spends first, and it is this act of spending that injects money into the economy. Public spending credits bank accounts, thus creating ex nihilo the money that will then circulate. The state is not the « cashier » of the economy; it is its « scorekeeper, » the one who writes the numbers on the board.

- Taxes Don’t Finance, They Destroy: According to this logic, taxes are not intended to « fill the state’s coffers. » These can never be empty. Paying taxes is the opposite of spending: it removes money from the economy. Taxes serve four main objectives:

- Create demand for money.

- Give value to money (you have to have it to pay your taxes).

- Regulate inflation by removing purchasing power.

- Influence behavior (redistribution, environmental taxes).

- Public Debt is the Net Financial Wealth of the Private Sector: « Public debt » is nothing more than the accounting reflection of the money that the State has created and injected into the economy and that has not yet been destroyed by taxes. Every euro of public debt corresponds to one euro of net financial assets2 for the private sector. One person’s « debt » is literally another person’s « wealth. » Issuing bonds is simply a change in the form of money: the State offers the private sector the opportunity to transform its savings (uninterest-bearing deposits) into a safe, interest-bearing investment.

- The Real Limit is Full Employment and Inflation, Not Financing: The only real limit to State spending is not financial, but real. The State can always create euros, but it cannot create engineers, wheat, or industrial capacity. If it spends beyond the economy’s productive capacity, the result is not bankruptcy, but inflation. The question is never « Do we have the money? », but « Do we have the real resources? »

This description of reality is a complete reversal of perspective. It transforms the state from a constrained actor into a powerful one, shifts the risk of bankruptcy to inflation, and changes the nature of debt from a burden to a mere accounting entry. It is precisely because it is so radically different from the dominant narrative that it struggles to be heard.

2.2 Identifying Narrative Obstacles

If the MMT narrative is technically coherent, why does it struggle so much to penetrate public debate? The reason is simple: it faces a series of powerful narrative obstacles. The problem lies not so much in the facts it describes as in the way our brains, formatted by the dominant narrative, receive them.

2.2.1 The Shock of Counterintuitiveness (The Cognitive Obstacle)

MMT requires a considerable cognitive effort: that of unlearning. Each key concept directly clashes with our intuition and our daily life experience.

- « Spending precedes income » runs counter to all our personal and familial experience.

- « Taxes destroy money » is an abstract and difficult-to-visualize concept, whereas the idea of a tax that « fills a coffer » is simple and concrete.

- « Taxes create a demand for money » is a counterintuitive idea because it reverses our usual conception: we think that taxes take what we already have. However, in MMT analysis, it is precisely the need to pay taxes that creates the need to obtain the state’s currency, thus making taxes the initial driving force of the monetary economy.

- « Debt is wealth » sounds like a semantic twist, an oxymoron, because our experience teaches us that debt is a burden.

This cognitive dissonance creates a reflex of rejection. The listener, faced with an idea that so violently contradicts their mental model, often prefers to dismiss it as absurd rather than question their own certainties.

2.2.2 The Absence of a Simple and Effective Metaphor (The Rhetorical Obstacle)

The dominant narrative has a golden metaphor: the « housewife » or the « good father. » It is simple, universal, and morally charged. MMT, on the other hand, struggles to find an equivalent.

- What is the MMT metaphor? « The State as banker »? « The State as scorekeeper »? « The State as currency monopolist »? These images are more precise, but they are technical, cold, and do not resonate with the collective imagination.

- They do not invoke strong, shared moral values. « Scorekeeping » is a neutral activity, while « managing a family budget » is a virtuous activity. One is a fact, the other is a fable. And fables are always more captivating.

2.2.3 The Suspicion of « Too Good to Be True » (The Moral Obstacle)

MMT’s central assertion, namely that the constraint of a sovereign state is not financial but real (the inflaton), is often viewed with immense suspicion.

- For many, this sounds like a « miracle recipe, » an invitation to limitless spending, opening the door to irresponsibility and hyperinflation. This is the famous critique of the « printing press. »

- This moral framework, based on scarcity, effort, and budgetary discipline, is not a natural part of human thought. It is the result of a patient historical construction, borne of decades of teaching, political discourse, media narratives, and institutional norms. Through repeated repetition, transmission, and integration, it has ceased to appear as just another framework and has become what Gramsci called « common sense »: an implicit, embedded framework that is difficult to question. This is why the intuitive rejection of MMT is not a result of a lack of logic or rigor, but of a cultural reflex. It is the expected effect of silently adhering to a narrative so deeply rooted that it no longer thinks of itself as a narrative, but as truth.

These three obstacles—cognitive, rhetorical, and moral—form a nearly impenetrable wall. They explain why a debate that should be technical and factual instantly becomes emotional and ideological. MMT doesn’t just ask people to change their minds; it asks them to change their narrative, and that is an infinitely more difficult task.

2.3 The Hypothesis of Different Logics: Who Can See Beyond the Narrative?

If understanding monetary « reality » is above all a question of going beyond a narrative, it is logical to ask who is best equipped to make this conceptual leap. Our hypothesis is that, paradoxically, economists trained in the dominant mold are perhaps the least able to do so. Their training has precisely conditioned them to think within the narrative. Other disciplines, on the other hand, cultivate logics that predispose to deconstruction.

2.3.1 The Sociologist and the Philosopher: The Deconstructors of Narratives

The sociologist, the political scientist, and the philosopher are trained to do one thing: never take a narrative at face value. Their job is to analyze the power structures, social constructs, and ideological functions hidden behind narratives.

- Faced with the metaphor of the « household state, » they don’t ask whether it’s true, but rather « Who benefits from it? »

- They immediately see the discourse on debt as a tool for social discipline and the legitimization of a political order.

- Their expertise lies in the ability to distinguish between discourse and practice, narrative and operational. They are therefore naturally inclined to see the orchestrated gap between public discourse and actual operations, this veritable staging of financial constraints, not as a technical anomaly, but as evidence of a tension between an official narrative and a functional necessity.

2.3.2 The Engineer: The Systems Analyst

The engineer brings a radically different, but equally effective, logic. He is not interested in moral narratives or political fables. He wants to know only one thing: « How does it really work? »

- His approach is systemic and functional. He looks at the « plumbing » (flows, inventories, feedback loops) to understand how the machine works.

- When faced with accounting diagrams, he doesn’t see a « debt, » but a closed loop. He sees the state as the energy source (the monopolist).

- He immediately identifies the « constraint » of Article 123 of the TFEU, which prohibits the ECB from granting overdrafts to European Union member states, as an unnecessary complication in the circuit, a « bug » or redundancy that slows down the system without changing its final output. His mind is oriented toward operational logic, not the narrative that surrounds it.

2.3.3 The Economist: Prisoner of the Narrative

Conversely, the economist trained in orthodoxy is often the greatest obstacle to his own understanding. His intellectual capital, his models, his career are built on the dominant narrative. Accepting MMT’s description would not amount to correcting an error, but to admitting that the very foundations of his own intellectual edifice are flawed. This is an existential challenge that few are willing to undertake. He has, in a way, become the high priest of a religion that he has forgotten is only a story.

This hypothesis suggests that the spread of a more accurate understanding of money will probably not come about through an internal conversion of the economics profession, but through hybridization, through the emergence of logics from other fields of knowledge that, by their very nature, are better equipped to see beyond the veil of fiction.

Part 3 – The Fabrication of Powerlessness: From Images in Our Heads to Cultural Hegemony

If MMT fails to gain traction in public debate, despite its technical coherence and its ability to shed light on the real mechanisms of money and public spending, it is not only because of its complexity or counterintuitive nature. We must go further and question not only the competing narratives, but also the conditions of production, dissemination, and internalization of these narratives. In other words: why do some ideas immediately seem « reasonable, » while others, even well-founded ones, seem literally inaudible?

To answer this question, three major thinkers offer complementary insights. Walter Lippmann3 helps us understand why the modern citizen, immersed in a flood of mediated information, is structurally disoriented. Noam Chomsky4 then dissects the mechanisms of this mediation: the active fabrication of consensus. Finally, Antonio Gramsci5 brings us back to the root of the problem: common sense itself, a product of cultural hegemony exercised by the ruling classes.

This section functions like a three-stage rocket. Each stage takes us a little further in understanding the ideological barrier that prevents the recognition of monetary « reality. »

3.1 Lippmann: The Disoriented Citizen in a Pseudo-Environment

In Public Opinion (1922), Walter Lippmann makes an observation that remains critically relevant today: citizens do not react directly to reality, but to a « pseudo-environment » made up of mental images, stereotypes, and narrative shortcuts. This mental world, essential for navigating a complex society, functions as a filter between us and reality.

« The real environment is far too vast, too complex, and too changeable for us to know it directly. We are not equipped to deal with such subtlety, variety, and combinations. And although we must act in this environment, we must reconstruct it on a simplified model before we can cope with it. »

The analogy « the state must manage its budget like a household » perfectly illustrates this idea. This simple, immediate, and emotionally charged shortcut becomes a prefabricated mental image that allows citizens to « think » about a complex reality without having to explore its mechanisms.

For Lippmann, this cognitive condition is not a moral failing of the citizen, but a structural constraint of modern democracy. In a world that is too vast and too complex, individuals must trust opinion-forming professionals: journalists, experts, columnists.

Citizens are therefore condemned to rely on intermediary narratives. But this raises a central question: who manufactures these narratives? With what objectives? And in whose interests?

To find out, we must turn to a radical critic of contemporary media democracy: Noam Chomsky.

3.2 Chomsky: The Media Mechanism of Manufacturing Consent

Sixty-six years after Lippmann, Noam Chomsky and Edward S. Herman published Manufacturing Consent (1988), a work that takes Lippmann’s expression and completely reverses its meaning.

Whereas Lippmann justifies the fabrication of consent as a necessity to steer opinion in the public interest, Chomsky, on the contrary, sees it as the very mechanism of political manipulation in democratic societies.

Their « propaganda model » is based on five media filters that determine what information is deemed acceptable:

- Media ownership: Most major media outlets are owned by industrial or financial groups, which have a vested interest in perpetuating the neoliberal system.

- Advertising as a source of revenue: The media depend on large corporations for their funding. However, these corporations have no interest in disseminating subversive ideas.

- Source selection: The « experts » invited to discuss economics come almost exclusively from the dominant orthodoxy—banks, government ministries, and liberal think tanks. Alternative voices (post-Keynesian, MMT) are marginalized or absent.

- Symbolic reprisals: Any dissenting voice is subject to symbolic reprisals (disqualification, mockery, invisibility), which discourages journalists from stepping outside the box.

- The dominant ideology: In the contemporary context, it is no longer anti-communism but austerity, debt, and rigor that structure the legitimate vision of the economic world.

In this system, the manufacturing of consent is a machine for producing the dominant narrative, selecting what deserves to be said and what can be thought. It is a « common sense » industry.

The result is striking: the state as household, debt as sin, and balanced budgets become the shared assumptions of a debate whose terms have been set in advance. Any proposal that challenges these frameworks is either ignored, mocked, or redefined as « unrealistic. »

But why are these narratives so well received? Why, even in the face of facts that contradict them, do they continue to impose themselves as natural truths? To answer this question, we must go down another level, to what the Italian thinker Antonio Gramsci calls cultural hegemony.

3.3 Gramsci: Cultural Hegemony as the Root of « Common Sense »

Antonio Gramsci, imprisoned by the fascist regime in the 1920s, developed a revolutionary theory of domination in his Prison Notebooks.

For Gramsci, the ruling class maintains itself not only through force, but above all through the ability to impose its vision of the world as universal and natural.

This is what he calls cultural hegemony: a process by which elites disseminate their values, interests, and interpretation of reality throughout society, until they become « common sense. »

This domination is exercised through all cultural channels—schools, churches, media, the arts—which function as apparatuses for disseminating the dominant ideology.

The idea that « the state must manage its finances like a household » is not just a narrative; It is a belief that has become a reflex, an incorporated prejudice, a mental automatism.

It is no longer perceived as a particular, historically situated idea, but as common sense. However, what Gramsci calls « common sense » is precisely that: ideology that has become a reflex, incorporated into the social body to the point where it becomes second nature. It acts like an inner language, speaking within us without our knowing where it comes from.

3.4 From Lippmann to Gramsci: The Synthesis

We can now articulate the three levels of analysis:

- Lippmann describes a sincere citizen, but lost in a world saturated with images and prefabricated narratives. His world is a theater of appearances that he mistakes for reality.

- Chomsky shows how these narratives are produced, selected, and disseminated by media filters that systematically favor dominant interests.

- Gramsci reveals why these narratives work so well: because they already inhabit our minds. They have become our common sense, our framework for interpreting the world, our implicit moral framework.

The manufacturing of consent is also a manufacturing of powerlessness. Not only does it prevent us from understanding that other economic policies are possible, but it deprives us of the imagination needed to conceive them.

This is why facts are not enough. It’s not just that they are filtered or denied; it’s that we have learned not to want to hear them. Citizens, educated in a culture of scarcity and constraint, spontaneously reject a theory like MMT, not because it is false, but because it seems to break the very laws of reality they have been taught to revere.

Part 4: Building a New Narrative – Facts Are Not Enough

If the economic battle is above all a battle of narratives, then simply presenting the facts, however rigorous, is not enough to win. Refuting a powerful story does not make it disappear; to replace it, one must be able to propose another, just as coherent, engaging, and, if possible, more desirable.

4.1 The Observation: Human Beings, Narrative Animals

Cognitive psychology and anthropology teach us that human beings are Homo Narrans, animals who think, understand, and organize the world through stories. Narratives are not mere entertainment; they are the primary tool through which we make sense of a complex reality. They create mental frameworks, causal schemas, and value scales that allow us to navigate the world.

Neurologist Antonio Damasio has shown that our decisions, even the most seemingly rational, are deeply rooted in our emotions. Yet, narratives are the main vector of emotions. An unemployment statistic informs us, but the story of a person who loses their job moves us. A balance sheet is a fact, but the story of a family « crushed by debt » is a tragedy.

This observation has radical implications for the economic debate. Presenting accounting diagrams and operational analyses (the « real ») is a necessary condition for establishing technical truth. It is the groundwork, essential for credibility. But it is not a sufficient condition for convincing and mobilizing.

For the description of monetary « reality » to become a force for social and political transformation, it must cease to be a mere « theory » or a set of counterintuitive « facts. » It must become the basis for a counter-narrative: a new story about money, the state, and our collective possibilities, one that is not only more just but also more hopeful than the austere narrative of coercion and fear. The task is thus no longer merely analytical; it becomes creative and political.

4.2 What New Metaphors? Replacing the Images, Changing the Frame

To build an effective counter-narrative, it is essential to attack the problem at its root: the metaphors that structure our thinking. It’s not a matter of finding simple « talking points, » but of proposing fundamental new images that completely reframe our perception of roles and issues.

Here are some ideas for replacing the toxic metaphors of the dominant narrative with more accurate and enlightening alternatives.

- Replacing « State as Household » with « State as Community Water Source »

The household metaphor is false because it presents the State as a mere user of money, when in fact it is its creator. We need an image that places it in its role as a source.- The new metaphor: Imagine a village built around a single spring. The villagers (the private sector) need water to live, grow crops, and trade. The guardian of the source (the State, via its central bank) is not itself a water consumer subject to scarcity; its role is to ensure that the flow is adequate for the community’s needs. Too little flow, and the fields dry up (recession). Too much flow, and the village floods (inflation). The question is never « does the guardian have enough water? », but « what is the right flow rate for the village’s prosperity? » This image makes the notion of monetary autonomy immediately intuitive.

- Replace « Public Debt » with « the Nation’s Net Financial Wealth »

The word « debt » is inherently negative. It must be neutralized by systematically showing its counterpart.- The new metaphor: The nation’s balance sheet is like a ledger. When the State spends more than it taxes, it records a liability (-100) for itself. But the immutable rule of double-entry bookkeeping requires that there be a corresponding asset (+100) somewhere. This asset is the net financial savings of households and businesses. Talking about « public debt » without mentioning the corresponding private savings is like reading only half of an accounting entry. We should therefore systematically talk about the « public financial balance, the counterpart of private savings. » This transforms an image of burden into a simple description of the financial structure of the economy.

- Replace « Printing Money » with « Crediting Accounts to Activate the Economy. » The image of « printing money » is archaic and evokes chaos and hyperinflation. It masks the reality of an electronic and targeted process.

- The new metaphor: Public spending is not a blind outpouring of money. It is a precise operation, like a « switch » or a « catalyst. » When the state decides to build a hospital, it doesn’t start a printing press. It credits the bank accounts of architects, construction companies, and suppliers. These credits are the « sparks » that activate real resources (labor, materials, machinery) that may have been unused. The question isn’t « where does the money come from? » but « do we have the engineers and the concrete available for the spark to catch and build something real? »

By changing the images, we change the framework of the discussion. We move from a moral debate about managing an imaginary scarcity to a technical and political debate about the optimal use of our real resources.

4.3 What New Values? From Constraint to Possibility

The dominant narrative is based on a foundation of negative values: fear (of bankruptcy, of the markets), guilt (of debt), and constraint (the scarcity of money). An effective counter-narrative cannot simply be technically correct; it must embody a set of alternative, positive, and desirable values. It must replace the narrative of resignation with a narrative of collective action.

4.3.1 Replacing Prudence with Potential

The orthodox narrative exalts budgetary « prudence, » which translates in practice into inaction. The counter-narrative must emphasize the notion of potential.

The new value: The real waste is not the public deficit, but the waste of real resources: unemployment (the waste of human potential), deteriorating infrastructure (the waste of physical capital), the inability to lead the ecological transition (the waste of our future). True « responsibility » is not to aim for balanced budgets, but to mobilize all available resources to achieve our society’s full potential. A balanced budget with 10% unemployment is a sign of profound political and moral failure.

4.3.2 Replacing Discipline with Democratic Sovereignty

The dominant narrative values « discipline » imposed by abstract rules and unelected actors (markets, rating agencies, European technocracy). The counter-narrative must rehabilitate democratic sovereignty.

The new value: Decisions on the allocation of the nation’s resources (what to build? What to produce? How to distribute?) are the most important decisions in a society. They must not be delegated to anonymous « markets » or unelected experts. They must be the result of democratic debate. Money is not a master imposing its laws on us, but a tool serving the objectives that the community sets for itself democratically. The challenge is not to obey the markets, but to put them back in their place: that of instruments serving society, and not the other way around.

4.3.3 Replacing Financial Scarcity with Managing Real Limits

The dominant narrative locks us into managing an imaginary financial scarcity. The counter-narrative must refocus us on managing real scarcities and real limits.

The new value: The true ethic of responsibility for the future is not to leave a low « public debt, » but to leave a viable planet. The debate must shift from abstract deficit figures to concrete, physical questions: how do we manage our carbon emissions? How do we preserve biodiversity? How do we manage our water, energy, and raw material resources? « Sustainability » is not a question of accounting, it is a question of ecology and physics. The counter-narrative proposes a form of ecological and social realism in opposition to the financial fetishism of the dominant narrative.

By moving from prudence to potential, from discipline to democracy, and from financial scarcity to managing real limits, we are not just changing the economic model. We are proposing a different societal project, a different vision of what we can accomplish together. This is what makes the counter-narrative not only credible, but also inspiring.

Conclusion: From Understanding to Conviction

At the end of this analysis, one conclusion is clear: the economic debate is less a confrontation of facts than a war of narratives. The persistence of the orthodox discourse on debt and austerity is not an intellectual accident, but a symptom of the victory of a narrative. Simple, moral, and deeply rooted in our culture, the narrative of the « state as household » and « debt as sin » has succeeded in shaping our perception of reality to the point of making political alternatives almost unthinkable.

Faced with this narrative bastion, approaches like MMT, which describe the actual functioning of the monetary system, struggle to gain traction. Although technically sound, they are narratively challenging: counterintuitive, they clash with our moral reflexes regarding scarcity and discipline. Their adoption requires a true Copernican revolution in thought.

The real challenge for those who aspire to a more accurate vision of the economy is therefore to move from technical understanding to political conviction. This requires becoming better storytellers. It involves constructing a powerful counter-narrative, capable of translating an operational description into a desirable story. A story that replaces images of fear and constraint with those of collective potential and democratic sovereignty.

However, this counter-narrative, as brilliant as it may be, can only prevail if a sufficient number of citizens become aware that they are the targets of narrative engineering. Transformation will not come from a new truth revealed from above, but from a wave of individual questioning. Real change in the world will only begin when each individual dares to ask the uncomfortable questions: « Why does this metaphor of housework seem so ‘natural’ to me? Who really benefits from the fear of debt? Why have I internalized the idea that I am not legitimate to think about these issues? »

Ultimately, the challenge goes beyond simply refuting an economic theory. It’s about breaking a form of collective spell, about seeing the strings of the ideological puppet. Only then can the battle of narratives truly be won. Not by imposing a new truth, but by restoring each person’s ability to desire and construct their own, in full awareness. The fight for a different economy is, above all, a fight to awaken minds.

Damasio, A. R. (1994). L’Erreur de Descartes : la raison des émotions. Odile Jacob.

Gramsci, A. (1978-1992). Cahiers de prison. Gallimard.

Herman, E. S., & Chomsky, N. (1988). La Fabrique du consentement. De la propagande médiatique en démocratie. Agone (édition de 2008).

Kelton, S. (2021). Le Mythe du déficit. Les Liens qui Libèrent.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Les métaphores dans la vie quotidienne. Les Éditions de Minuit.

Lippmann, W. (1922). Public Opinion. Harcourt, Brace and Company.

Mosler, W. (1995). Soft Currency Economics. Self-published.

Mosler, W. (2010). The Seven Deadly Innocent Frauds of Economic Policy. Valance Co., Inc.

Notes

1 See the article here : https://mmt-france.org/2025/07/06/quest-ce-que-le-reel-comment-nos-evidences-nous-alienent/

2 Considered in the context of the state’s monopoly on its currency, this concept is at the heart of MMT. It distinguishes MMT from all other monetary approaches, both orthodox and heterodox, which reason in gross terms, not in net terms. In the logic of MMT, NFAs are the financial basis on which the economy rests; it is the financial wealth that remains with the economic agent once all his debts have been settled. They constitute the part of financial wealth that does not come from indebtedness (bank credit), but from final payments (in relation to the state through public spending).]

3 Walter Lippmann (1889–1974)

Journaliste et intellectuel américain, Lippmann est célèbre pour son livre Public Opinion (1922), dans lequel il montre que l’opinion publique se construit sur des « stéréotypes » plutôt que sur une information directe. Il a forgé l’expression manufacture of consent (« fabrication du consentement ») pour désigner la façon dont les médias façonnent les perceptions collectives.

4 Noam Chomsky (born in 1928)

An American linguist, philosopher, and political activist, Chomsky is a leading critic of the media and US foreign policy. In Manufacturing Consent (co-written with Edward Herman), he explains how the mainstream media serves the interests of economic and political elites by controlling and filtering information. He is also the founder of generative linguistics.

5 Antonio Gramsci (1891–1937)

An Italian intellectual and communist activist, Gramsci is known for his theory of « cultural hegemony. » He demonstrates that the ruling classes maintain their power not only through coercion but also by imposing their worldview as « normal. » His Prison Notebooks are a major reference in political philosophy and sociology.

oooooo

I see a lot of the respectable commentators from the left all fit nicely into the neoliberal paradigm of governments needing to balance budgets. Which is what leads to asuterity. And undermines all of their progressive aims. Patricia makes the point very well.

Aipamena

Patricia@PatriciaNPino

abu. 7

Im bored of the pretence that govt is like a household. That the currency issuing govt has to find currency before it can spend it. Stop portraying Reeves’ gratuitous austerity as a mishandling of the ‘respectable’ aim of lowering the deficit. The aim is not respectable. x.com/gbnews/status/…

oooooo