Sarrera gisa, ikus ondokoak:

Austeritatearen hipokresia: armagintza

Armagintza eta ekonomia (1989tik)

Segida:

@tobararbulu # mmt@tobararbulu

The arms race again – Part 1 https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=62612

ooo

The arms race again – Part 1

June 11, 2025

The Chair of the Finance Committee in the Irish Parliament invited me to make a submission to inform a – Scrutiny process of EU legislative proposals – specifically to discuss proposals put forward by the European Council to increase spending on defence. This blog post and the next (tomorrow) will form the basis of my submission which will go to the Joint Committee on Finance, Public Expenditure, Public Service Reform and Digitalisation on Friday. The matter has relevance for all countries at the moment, given the increased appetite for ramping up military spending. Some have termed this a shift back to what has been called – Military Keynesianism – where governments respond to various perceived and perhaps imaginary new security threats by increasing defence spending. However, I caution against using that term in this context. During the immediate Post World War 2 period with the almost immediate onset of the – Cold War – nations used military spending as a growth strategy and the term military Keynesianism might have been apposite. These nation-building times also saw an expansion of the public sector, which supported expanding welfare states and an array of protections for workers (occupational safety, holiday and sick pay, etc). However, in the current neoliberal era, the increased appetite for extra military spending is being cast as a trade-off, where cuts to social and environmental protection spending and overseas aid are seen as the way to create fiscal space to allow the defence plans to be fulfilled. That trade-off is even more apparent in the context of the European Union, given that the vast majority of Member States no longer have their own currency and the funds available at the EU-level are limited. We will discuss that issue and more in this two-part series.

Recent Trends in Military Spending

It is clear that global defence spending has accelerated in recent years in the aftermath of the Russian invasion of the Ukraine.

Most of the Member States of the – North Atlantic Treaty Organisation – have increased the proportion of government spending devoted to military spending both relative to the size of their economies (measured by GDP) and as a share of total government spending.

Once the tensions associated with the Cold War were reduced, NATO nations reduced their focus on military expenditure.

In some cases, this was articulated as allowing social expenditures to expand.

The underlying premise, which for many currency-issuing nations was false, was that the governments had financial constraints and could not maintain the levels of military expenditure that were common in the immediate World War 2 period if the government wanted to increase spending elsewhere.

There was obviously a real resource constraint that would be binding at full capacity which would define some inflation ceiling in terms of total nominal expenditure.

But in the period after the OPEC crisis of the 1970s, economies rarely achieved anything close to full capacity and so those real resource constraints were non-binding for most countries during this period.

With the onset of renewed tensions on the European continent, and rumblings in Asia, as well as the rapidly deteriorating situation in the Middle East, the sense of security, which saw reduced focus on military expenditure by governments has been compromised.

We have seen remarkable statements from global leaders in recent years expressing that insecurity.

On March 30, 2024, the BBC report – War a real threat and Europe not ready, warns Poland’s Tusk – quoted Poland’s Prime Minister as saying that war is:

… no longer a concept from the past … It’s real and it started over two years ago …

We are living in the most critical moment since the end of the Second World War …

I know it sounds devastating, especially to people of the younger generation, but we have to mentally get used to the arrival of a new era. The pre-war era.

Similar remarks were made on May 22, 2024, by the then Secretary of State for Defence in his – London Defence Conference 2024 Defence Secretary keynote.

He reflected on the period of relative peace as a “golden era” compared to the present where “ruthless, rule-breaking” nations had moved the global environment from a:

… post-war to a pre-war era.

He said that “An axis of authoritarian states led by Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea have escalated and fuelled conflicts and tensions.”

He said this justified a significant increase in government spending on the military.

And most governments have followed suit.

The International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) report (February 12, 2025) – Global defence spending soars to new high – noted that:

In 2024, global defence spending reflected intensifying security challenges and reached USD2.46 trillion, up from USD2.24trn the previous year. Growth also accelerated, with the 7.4% real-terms uplift outpacing increases of 6.5% in 2023 and 3.5% in 2022. As a result, in 2024, global defence spending increased to an average of 1.9% of GDP, up from 1.6% in 2022 and 1.8% in 2023.

A Briefing Document prepared for the Australian Parliament – Rising global defence expenditure (June 4, 2025) – by Nicole Brangwin showed that there has been a 7.4 per cent real growth in global defence spending in 2024 (relative to 2023) and the proportion of GDP devoted to defence rose from 1.8 to 1.94 per cent.

It was also noted, that data from the Stockholm International Peace and Research Institute (SIPRI), shows there has been a “37% global increase in military spending over the last decade, with the single largest increase since the end of the Cold War occurring in 2024”.

And the expectation for 2025 is for an even greater increase.

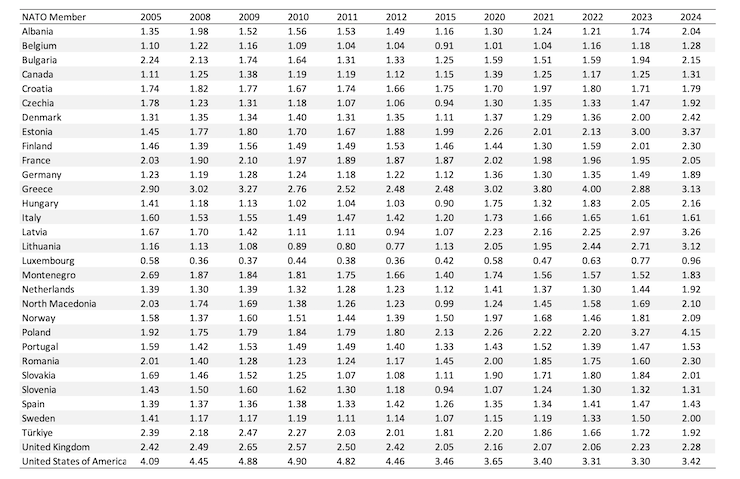

Table 1 shows the NATO Member-States spending on military as a percent of GDP for selected years.

Only four of the nations shown reduced their military spending as a percent of GDP.

Some of the countries closest in geographic terms to the Russian-Ukraine frontiers have expanded their military commitments relative to the size of their economies significantly.

Non-NATO countries have also followed suit.

Table 1 NATO Military Spending as a Percent of GDP, 2000 to 2025

Source: SIPRI Military Expenditure database.

Note: Iceland omitted due to lack of data.

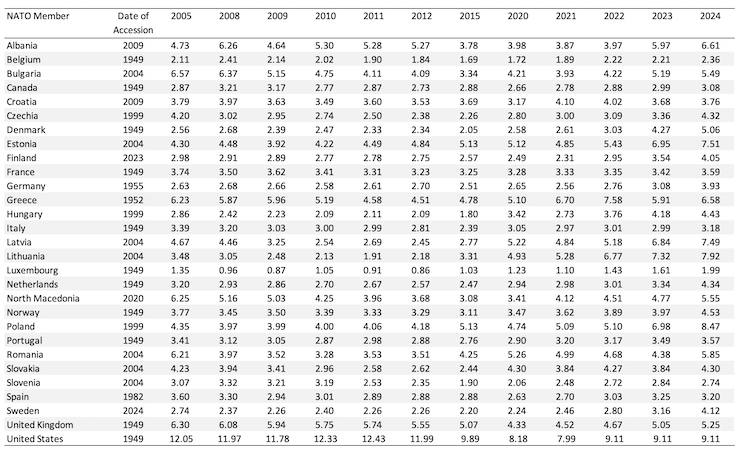

Many governments are also increasing the proportion of their total spending towards military purchases.

Table 2 NATO Military Spending as a Percent of Total Government Spending, 2000 to 2024

Source: Table 1.

Note: Iceland, Türkiye, and Montenegro omitted due to lack of data.

Military Keynesianism

As part of the political strategies that have been deployed to justify this rather significant realignment of government priorities, the term – Military Keynesianism – has been bandied around.

Military Keynesian refers to policy decisions to utilise defence spending as a growth strategy.

On April 14, 1950, the US Department of State and Department of Defense presented President Truman with the secret report – NSC 68 – or United States Objectives and Programs for National Security – which “provided the blueprint for the militarization of the Cold War from 1950 to the collapse of the Soviet Union at the beginning of the 1990s.”

The sentiments expressed in that document could easily relate to the current discussions about the need for more defence spending in the light of elevated security concerns.

We read that (p.4):

… the Soviet Union … is animated by a new fanatic faith1 antithetical to our own and seeks to impose its absolute authority over the rest of the world. Conflict has, therefore, become endemic and is waged, on the part of the Soviet Union, by violent or non-violent methods in accordance with the dictates of expediency. With the development of increasingly terrifying weapons of mass destruction, every individual faces the ever-present possibility of annihilation should the conflict enter the phase of total war …

The Report noted that unlike the Soviet economy, which it described as a ‘war economy’. the US had been devoted “to the provision of rising standards of living” (p.25) and that placed it at a military disadvantage.

To justify its recommendation for greater military spending by the US government, the Report stated (p.28) that:

… the United States could achieve a substantial absolute increase in output and could thereby increase the allocation of resources to a build-up of the economic and military strength of itself and its allies without suffering a decline in its real standard of living … With a high level of economic activity, the United States could soon attain a gross national product of $300 billion per year … Progress in this direction would permit, and might itself be aided by, a build-up of the economic and military strength of the United States and the free world …

This type of argument defined ‘military Keynesianism’ as a structural growth impulse, rather than a cyclical response to deficient economic cycle spending by the non-government sector.

However, that does not preclude using military spending to kick-start an economy during a recession.

In the latter context, it is widely argued that the Great Depression only came to an end when governments increased military spending to prosecute the Second World War effort.

For example, John Feffer in his 2009 article – The Risk of Military Keynesianism – reflected on the fiscal choices facing governments during the Global Financial Crisis and said:

With government budgets shrinking and the economic crisis putting greater pressure on social welfare programs, a shift of money from military budgets to human needs would appear to be a no-brainer. But don’t expect a large-scale beating of swords into ploughshares. In fact, if early signs are any indication, governments will largely shelter their military budgets from the current economic crisis.

Reference: Feffer, J. (2009) ‘The Risk of Military Keynesianism’, Foreign Policy in Focus, February 9.

There are many issues that have been raised against governments adopting military expenditure as a primary growth strategy, which we do not canvas here.

The problem we do address is that Feffer invoked the ‘trade-off’ card, like most commentators that want to criticise any buildup in military spending by governments.

Accordingly, to accommodate the increased defence spending, cuts to social and other spending are required.

The alternative way of saying this in the words of Feffer is:

At a time when we urgently need funds for the food crisis, the energy crisis, the climate crisis, the AIDS crisis, and other looming crises — all of which threaten human security — military spending is nowhere near the top of the global agenda.

Which implies some financial constraints on governments and within that constraint there are better things for governments to spend their ‘constrained’ cash on than defence procurements.

This narrative is dominant in the current discussions about the need for increased military spending.

On June 2, 2025, the UK Guardian article – Labour pushes ‘military Keynesianism’ to win support for defence spending – reported that:

This “military Keynesianism” was emphasised on Sunday morning when ministers announced plans to build six new munitions factories, which would in time create 1,000 jobs and support a further 800, the Ministry of Defence said.

The British government has claimed that the rapid expansion in military spending would help “create skilled jobs, particularly outside London, such as at shipyards in Barrow, Devonport, Glasgow and Rosyth.”

They justified “diverting funds from overseas development aid” the government could reinforce “the British industrial base”.

There is some truth to that argument even though the government’s decision is being driven by the fiction that it faces a financial constraint.

The truth is that diverting spending that benefits the rest of the world (the ODA) and channelling it into the domestic economy will enhance GDP and employment growth in Britain.

The morality of that decision is highly questionable.

But there is another issue that is most relevant in the case of the European Union’s plan, which we scrutinise later in this submission.

Notwithstanding whether it is desirable or not for Britain to be joining the ‘arms race’, if there is real resource space to accommodate the extra nominal spending on defence procurements in Britain without reaching an inflationary ceiling, then the British government could have simply increased its spending on the military without compromising its global responsibilities to support poorer nations through ODA.

The fact that they claimed the diversion was necessary reflects their adherence to flawed fiscal rules that assume the British government is financially constrained in terms of its sterling spending capacity.

We will return to that issue in Part 2.

The other interesting aspect of the data presented in the Tables above is that governments did not seem to rely on military expenditure during the GFC to restore growth to their economies.

For the NATO countries, military spending as a share of GDP fell between 2008 and 2012 in 22 out of the 31 NATO Member States for which there is compatible data, while 2 of the States reported stable military spending relative to GDP.

So military Keynesian was not seen as a dominant fiscal strategy during the GFC.

It is also not a good characterisation of what is happening in the current environment, a point we will turn to in Part 2.

Conclusion

In Part 2, I will focus on the specific proposals being put forward by the European Commission to increase military spending.

oooooo

The arms race again – Part 2 https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=62617

ooo

The arms race again – Part 2

June 12, 2025

This is the second part of my thoughts on the current acceleration in military spending around the world. The first part – The arms race again – Part 1 (June 11, 2025) – focused on background and discussed the concept of ‘military Keynesianism’. In this Part 2, I am focusing more specifically on the recent proposals by the European Commission to increase military spending and compromise its social spending. The motivation came from an invitation I received from the Chair of the Finance Committee in the Irish Parliament to make a submission to inform a – Scrutiny process of EU legislative proposals – specifically to discuss proposals put forward by the European Council to increase spending on defence. The two-part blog post series will form the basis of my submission which will go to the Joint Committee on Finance, Public Expenditure, Public Service Reform and Digitalisation on Friday. In this Part, I focus specifically on the European dilemma.

The democratic deficit – Article 122 and more

An issue that has become more prominent since the introduction of the common currency in the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) is the – Democratic legitimacy of the European Union – which leads to discussions about a – Democratic deficit.

The concept of a ‘democratic deficit’ emerges because the European Commission and Council has sought over the decades to centralise power and policy while ignoring the demands of voters in the Member States.

Even the foundation of the EMU evaded legitimate democratic processes.

The issue is not new: the European Parliament was created in 1979 as a response to the accusations that the European Union did not have democratic legitimacy.

The tendency under the fiscal rules and surveillance mechanisms of Member State macroeconomic policy for technocratic oversight from Brussels has reinforced the critics.

That tendency was on full display in 2015, when the major European institutions (Commission and ECB) combined with the unelected global body – the International Monetary Fund (IMF) as the Troika and forced the democratically-elected Greece government to defy the results of a popular referendum and accept harsh austerity measures, which have permanently crippled the nation.

The Troika even threatened to force the Greek banking system into insolvency if the Greek government did not accept the unilateral imposition of conditionality associated with the so-called ‘bail-out’.

The fiscal architecture of the European Union also allows for technocratic interventions into Member State fiscal policy deliberations and outcomes, which are contrary to the notion of accountability to a demos that elects the government.

It is hard to construe the European Commission as being consistent with democratic accountability (that is, to the people) when it is unelected, yet it exercises key legislative force in the union.

Further, the European Parliament, which was established to enhance the legitimacy of the union, does not have the capacity to determine EU law.

The so-called “ordinary legislative procedure or co-decision” (see the European Parliament’s information on – Legislative Powers) – makes it clear that legislation is proposed by the European Commission and “adopted” by the Parliament and the Council.

A European Parliament Library Briefing (October 24, 2013) – Parliament’s legislative initiative – opens (p.1):

At EU level, in contrast, the right to initiate legislation is reserved almost entirely for the European Commission (EC) …

It is suggested that the EC’s initiative monopoly was originally rooted in the mistrust of the political process in post-war Europe. As a

consequence, European integration and the identification of the “general interest” of the Communities were entrusted to a technocratic

authority, whose decisions were to be legitimated by its expertise and performance.

The capacity of the European Parliament has relevance for how we assess the recent European Commission proposals, which we outline next.

As part of the global race to arms and given the proximity of two major military conflicts in the world, it is unsurprising that the European Union has introduced two new proposals to cover what they see as defining necessary action to deal with urgent new security threats, presumably from Russia.

The first proposal – COM/2025/0122 – which is a Proposal for a COUNCIL REGULATION establishing the Security Action for Europe (SAFE) through the reinforcement of European defence industry Instrument.

It was introduced on March 19, 2025 and is being justified under Article 122 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union which says that:

1. Without prejudice to any other procedures provided for in the Treaties, the Council, on a proposal from the Commission, may decide, in a spirit of solidarity between Member States, upon the measures appropriate to the economic situation, in particular if severe difficulties arise in the supply of certain products, notably in the area of energy.

2. Where a Member State is in difficulties or is seriously threatened with severe difficulties caused by natural disasters or exceptional occurrences beyond its control, the Council, on a proposal from the Commission, may grant, under certain conditions, Union financial assistance to the Member State concerned. The President of the Council shall inform the European Parliament of the decision taken

The European Parliament briefing on this proposal (April 11, 2025) – Legal bases in Article 122 TFEU: Tackling emergencies through executive acts – noted that the Council has identified two legal bases for being able to agree to this European Commission proposal without involving the European Parliament in any way.

The March 19 proposal seeks to advance the so-called Security Action for Europe (SAFE), which is just word soup to allow the Council to reallocate the EU budget towards a massive escalation in defense spending.

The justification appears to be on the basis of an EU ’emergency law’.

Article 122 has been used previously:

1. To establish a – European financial stabilisation mechanism (May 11, 2010) – during the Global Financial Crisis.

2. During the early period of the COVID-19 pandemic to justify the provision of emergency support under – Council Regulation (EU) 2020/521 (April 14, 2020).

3. To establish a – European instrument for temporary support to mitigate unemployment risks in an emergency (SURE) following the COVID-19 outbreak (May 19, 2020).

4. More recently, in the context of the Ukraine situation, Article 122 was invoked to justify the establishment of the – coordinated demand-reduction measures for gas (August 5, 2022).

5. And further, in the Ukraine context, the – emergency intervention to address high energy prices (October 6, 2022).

These developments have not been without controversy.

The European Parliament’s concern is that by unilaterally accepting this proposal, the action limits democratic legitimacy.

While there have been some joint discussions about the application of Article 122 following its invocation during the COVID-19 crisis, it remains that the Parliament does not have determinative oversight on proposals that draw on Article 122 for justification.

The issue is that while Article 122 is a vehicle for addressing ’emergencies’, the reality is that the way in which it has been used suggests policy development that is more structural rather than reactive.

The – Report of the Franco-German Working Group on EU Institutional Reform (September 18, 2023) – Sailing on High Seas: Reforming and Enlarging the EU for the 21st Century – was published as uncertainty about European security was rising.

It noted that (p.11):

Russia’s brutal war on Ukraine, rising tensions within and across regions and the weakening of global order structures have shattered the certainties on which the EU was built. Transnational challenges, such as climate change, security threats and food and health crises urgently require cooperative solutions. With Russia’s war on Ukraine, the geostrategic role of the EU has dramatically changed through the large-scale military, humanitarian, financial and diplomatic support it provides. The debate about the EU’s capacity to act and its overall sovereignty has intensified and the continent’s architecture and the EU’s relationship with its neighbours in the East and South need to be thoroughly rethought due to the grave threats posed to the European security order.

One would surmise that the election of President Trump for a second term would elevate the sense of urgency expressed in this statement from the Franco-German Working Group.

The Working Group reflected on the perception that democratic legitimacy is lacking in the EU.

It was noted that a major criticism of the evolution of the EU has been based on the claim that the EU “has extended its competencies too far” and the “preconditions for a classical democracy … are missing” (p.13).

A problem the Working Group identifies is that “because of various crises … speedy decisions are of the essence” and the unwieldy European decision-making institutions are ill-suited to respond with such alacrity (p.14).

As a consequence, the urgency to respond to crises has meant that decision mechanisms “have de facto become EU powers” (p.14) and that provokes the perception of an increasing democratic deficit in the EU.

In response to these concerns, the Working Group recommended that (page 28):

Article 122 TFEU should be amended to include the EP in the decision-making on measures to address emergencies or crises.

There has been other arguments to support the view that the EU has by ‘stealth’ exceeded its competencies as it has responded to various crisis in recent decades.

In an – Op-Ed: “Article 122 TFEU and the Future of the Union’s Emergency Powers (January 25, 2024)- which was a contribution to a ‘Symposium on EU Enlargement’, academic lawyer Paul Dermine argued that:

It is certain that Article 122 stands for an intergovernmental, technocratic and output-based vision of EU politics, which only provides for limited, indirect democratic legitimacy, widely deemed unsatisfactory, especially in view of the transformative, structural impact the clause now has on the EU polity.

Reference: Dermine, P. (2024) ‘Op-Ed: “Article 122 TFEU and the Future of the Union’s Emergency Powers”’, EULaw Live, January 25.

He recognises, as did the Franco-German Working Group, the dilemma faced by European policy makers – how to respond quickly to emergencies when such a response risks adding to the democratic deficit?

While many reforms for Article 122 have been suggested by various parties, the relevance here is that once again the Commission is seeking to use this Article to respond to an perceived emergency with policies that, if implemented, will have long-term structural consequences for the EU and its citizens.

The use of Article 122 in that regard is consequential and problematic.

The second proposal – COM(2025)123 – which is a Proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL amending Regulations (EU) 2021/1058 and (EU) 2021/1056 as regards specific measures to address strategic challenges in the context of the mid-term review.

It was introduced on April 1, 2025 and is being justified under Articles 175, 177, 178, 294 and 322 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

I discuss aspects of this proposal below.

The SAFE proposal

The English version of the SAFE proposal can be downloaded – HERE.

The proposal emerged out of meetings between EU Head of State or Government in March 2022, which agreed to ‘”bolster European defence capabilities” in light of Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine’ (p.1).

It was clear that Member States largely were procuring military equipment “alone and from abroad”, which was seen as problematic in terms of building a European capability.

The reaction by the US has also reinforced the European desire to seek a path of self-determination with regard to security matters.

The conclusion (p.2):

… the Union and its Member States must immediately and massively scale up their efforts to invest in their industrial capacity, hence ensuring their defence more autonomously.

And the need identified “mobilising the Union budget to support and accelerate national investments through a new financial EU instrument” (p.2).

Moreover, it was proposed to activate:

… the national escape clause of the Stability and Growth Pact will support Member States’ public investments and expenditures in defence.

SAFE proposes to provide loans to Member States “to enable them to carry out the urgent and major public investments” to expand their military capacity through a “common procurement” mechanism (p.2).

Problems with the SAFE proposal

There are many problems with the SAFE proposal.

In terms of the “budgetary implications”, the European Commission will borrow up to 150 billion euros in the financial markets to underwrite the loans to the Member States.

The Proposal contains a bevy of typical EU rules and restrictions pertaining to the loan procedures.

But essentially, it is another vehicle for encumbering the Member States with extra financial burdens, in a system where the ‘federal’ capacity is absent but essential given the type of threat the proposal seeks to address.

Once again it is an example of a monetary architecture that is not fit for purpose – more on that below.

The proposal still is dependent of the Member State’s fiscal capacities, which under the EMU architecture are rendered insufficient to deal with the type of emergency that is being articulated.

Note: I do not concur with the view that the threat is of the scale and urgency articulated in the proposal.

The SAFE proposal talks about “activation of the existing flexibility within the framework of the Stability and Growth Pact” (SGP) but does not offer any specific suggestions.

During the emergency restrictions pertaining to the COVID-19 pandemic, the ‘general escape clause’ within the SGP was activated to allow Member States to exceed the fiscal thresholds.

But subsequently the Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP) once again become active and several Member States now find themselves in breach of the fiscal rules and are being forced by the Commission to correct their fiscal balances through austerity measures, which including cuts to social spending.

There has been a suggestion in the White Paper – European Defence and the ReArm Europe Plan/Readiness 2030 (issued March 19, 2025) – of an extra 1.5 per cent of GDP being added to the SGP fiscal deficit threshold but countries already caught within the EDP will struggle.

The SAFE proposal is part of the White Paper strategy.

Given recent history, the proposal risks forcing the Member States into damaging austerity, overseen by both the Commission and the ECB through its – Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI) – which was introduced on July 21, 2022.

The TPI is effectively an extension of the government bond buying programs conducted by the ECB that started in May 2010 in the guise of the Securities Market Program.

While the sequence of asset-purchasing programs have saved the EMU from break up, in the sense that they have effectively funded the fiscal deficits of nations and appeased the financial markets, thus maintaining solvency across the Member States, they have also been accompanied by harsh conditionality that has defined the austerity era for Europe and led to major cuts in social expenditure and other worthwhile spending.

The operation of the TPI is closely embedded with the EDP, which makes it obvious that a Member State will encounter difficulties and be forced into fiscal austerity should the debt obligations incurred under the SAFE push the fiscal balance into the EDP.

Rather than becoming a unifying strategy, it is easy to see the SAFE becoming another noose around the prosperity of the Member States, particularly those that are already sailing close to or are already in the claws of the EDP.

In relation to the claim that the EU is engaging in military Keynesianism, the reality does not support that view.

The growth envelope of the Member States is limited by the SGP and the structure of the individual economies.

As noted above, Member States, predominantly procure military equipment from beyond their borders – particularly from the US.

The import dependency of various Member States in relation to defence purchases has significant implications for the expenditure multiplier values arising from military expenditure for Europe.

The expenditure multiplier is the measure of the extra GDP that accompanies a unit increase in autonomous spending in an economy.

The concept of military Keynesianism was predicated on high multiplier values and in the immediate Post World War 2 decades the supply chains were more concentrated within national borders so that large government contracts for many nations were less prone to large import leakages.

That situation has now changed with complex global supply chains within manufacturing and assembly being the norm.

The SIPRI analysis (March 10, 2025) – Ukraine the world’s biggest arms importer; United States’ dominance of global arms exports grows as Russian exports continue to fall – noted that:

Arms imports by the European NATO members more than doubled between 2015–19 and 2020–24 (+105 per cent). The USA supplied 64 per cent of these arms, a substantially larger share than in 2015–19 (52 per cent). The other main suppliers were France and South Korea (accounting for 6.5 per cent each), Germany (4.7 per cent) and Israel (3.9 per cent).

This means there will be considerable leakage from the domestic economy of Member States investing in military expenditure under the SAFE instrument.

Which, in turn, means the growth benefits of the loan-based expenditure will be reduced.

By the time the fiscal flexibility under the proposal ends (after 4-years) and the EDP is resumed in full, Member States that have borrowed under this program may find the growth dividends from the spending low and the spending cuts necessary to fit in to the SGP rules given the extra interest payments on the military debt large.

The EU will insist those problems remain at the Member State level which makes a mockery of the rhetoric about the need for solidarity in meeting the perceived threat.

The likely outcome is that Member States will have to make further cuts to social expenditure to meet the surveillance conditions under the EDP.

Such expenditure is likely to have a higher multiplier than the military expenditure, which means the resulting damage to GDP growth will be higher once the fiscal rules are fully reinstated.

What about the EU-level expenditure?

The so-called – Cohesion Fund – was designed to provide convergence within the EU between Member State outcomes.

On April 1, 2025, the Commission proposed an – amending Regulations (EU) 2021/1058 and (EU) 2021/1056 as regards specific measures to address strategic challenges in the context of the mid-term review – which among other things:

… presents an opportunity for Member States to redirect 2021-2027 resources towards investment in defence capabilities …

It is easy to see what will happen as a result of such ‘redirection’.

Member States will be pressured to shift social and environmental funds received through the Cohesion Fund into military expenditures.

Already there is a massive shortfall in spending on energy transformation, dealing with climate effects on the food supply (desertification), advancing the digital transformation of the nations, reducing poverty, restoring quality to health systems and more.

Trying to fit a significant boost to military investments into this highly constrained envelope will prove to be impossible.

A final observation is that the SAFE instrument relies on Member State take-up of the loans.

This presents a curious dilemma.

On the one hand, the perceived security threat pertains to the European continent as a whole and would, if valid, require a uniform European response.

Yet, on the other hand, the SAFE instrument will only lead to enhanced military capacity if the Member States access the borrowing.

If so I suspect many will be pushed over a fiscal cliff that will then lead to punishment from the Commission under the EDP some time down the track.

There is also no incentive for individual Member States to cooperate with each other to ensure efficient procurement.

Thus, the solution does not match the perceived need.

Conclusion

Once again, the EU is tied up in a sub-optimal response because its governance and monetary architecture is dysfunctional.

The increased military expenditure will starve the continent of investments in climate response, poverty reduction, skill upgrading, health care, housing and digitisation.

It is another EU-designed recipe for disaster.

oooooo