Imports, Monetary Sovereignty, and Misplaced Blame: A Monetary Refutation of Steve Keen with Policy Sequencing

Author: Roberto Bazzichi / Fabio Bonciani under the supervision of Warren Mosler

Jun 23, 2025

Abstract:

Steve Keen argues that trade surpluses create money while trade deficits destroy it, and he criticizes Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), particularly Warren Mosler, for claiming that trade deficits benefit the importing nation. This paper reasserts the MMT position with an extended analysis of monetary operations, sectoral balances, and international policy sequencing. We show that trade deficits are not only non-destabilizing for monetarily sovereign nations but represent a real gain—provided full employment is maintained. Exporting nations, meanwhile, often adopt policies that are strategically self-defeating in the long run.

1. Introduction

Keen’s critique of MMT, particularly Mosler’s assertion that “imports are real benefits, exports are real costs,” hinges on the idea that exports create money in the exporting country, while imports destroy money in the importing country. This view misrepresents monetary operations under sovereign fiat currency regimes and ignores the real-versus-nominal distinction emphasized by MMT. We begin by restating the correct framework.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

2. Trade in Sovereign Fiat Systems: Real vs. Financial Flows

In a system where a government issues its own non-convertible currency and lets the exchange rate float, international trade is a real exchange: goods and services cross borders, while financial flows involve the shifting of existing currency balances. When the U.S. imports from China:

- U.S. consumers pay in dollars.

- Chinese exporters receive dollar deposits held in U.S. bank accounts.

These dollars never “leave” the dollar zone. They are claims against the U.S. financial system. The Federal Reserve does not reduce its monetary base due to imports. There is no destruction of U.S. dollars.

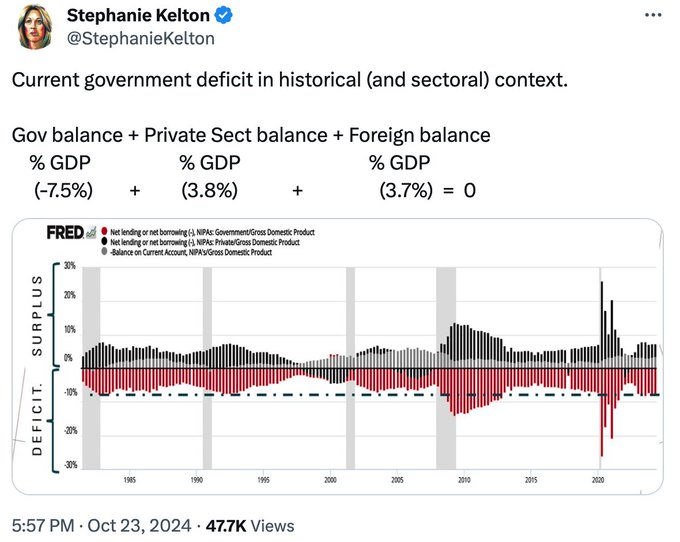

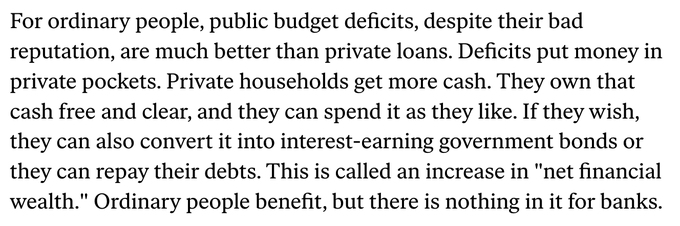

3. Sectoral Balances and Net Financial Assets

Government deficits create net financial assets (NFAs) for the non-government sector. Trade surpluses, by contrast, bring in foreign currency—not domestic money. Exporters receive foreign-denominated deposits (e.g., U.S. dollars), not NFAs in their own currency. When they exchange those dollars for local currency, the central bank (or a commercial bank) creates new domestic money as part of the FX transaction.

This is a form of “off-balance-sheet” deficit spending: the central bank injects local currency into the economy without this appearing in formal fiscal accounts. Crucially, the domestic currency creation could occur regardless of whether foreign reserves were accumulated—the trade surplus merely provides a political or institutional justification. The MMT framework distinguishes between vertical (sovereign to non-sovereign) and horizontal (private-to-private) money creation, clarifying that only the sovereign can inject NFAs in its own currency.

4. The Sequence: Trade Deficit, Fiscal Offset, and Real Gains

Keen treats trade deficits as a leakage from domestic demand. Yet this is only true if no fiscal response occurs. In practice, a sovereign government can—and often does—respond to trade-induced reductions in domestic demand via tax cuts or public spending. This maintains employment and output.

The key insight: what Keen calls a cost is actually a trigger for fiscal space. Imports reduce real resource use domestically, allowing the government to expand spending without overheating the economy. Rather than being an additional benefit, this is a fuller understanding of the basic MMT point: the benefit of importing real goods without sacrificing full employment.

However, this real benefit must be contextualized. Persistent trade deficits in strategic sectors can, over time, lead to dependencies that may compromise national resilience. The advantage remains real in the short run but must be weighed against potential long-term vulnerabilities.

5. China’s Policy and Off-Balance Sheet Deficit Spending

Keen implies that China grew by accumulating U.S. dollars, suggesting that the U.S. trade deficit funded China’s growth. But the real stimulus came from China’s domestic currency injections. The Chinese government bought dollars from exporters using renminbi, injecting local currency into the economy. This is what Mosler calls “off-balance-sheet” deficit spending: central bank operations that expand domestic balances without appearing in fiscal accounts.

Thus, China’s growth was funded not by U.S. dollars being spent domestically (they never were), but by renminbi created internally.

6. Dollarization and the Export-Led Trap

China chose to suppress its exchange rate and accumulate dollar reserves to maintain export competitiveness. This policy propped up the dollar and suppressed domestic demand. Had China let the renminbi float, trade surpluses would have been smaller, and internal consumption higher.

The real strategic error was China’s own: it sacrificed macroeconomic balance to support exporters, a decision that benefitted U.S. consumers. The U.S. did not force this arrangement—it simply allowed it.

7. Who Needs to Export? A Moslerian Clarification

All nations need export revenues to buy imports—unless they obtain those imports for free from nations desiring to net export. In other words, a country can consume more than it produces in tradables when foreign exporters willingly accept its currency in exchange for real goods.

This is not exploitation, but a voluntary outcome of global trade imbalances: the exporting country desires to accumulate financial assets in the importer’s currency. The key MMT insight is that a monetarily sovereign country with a floating exchange rate can sustain trade deficits without solvency risk, as long as real resource constraints are respected and full employment is maintained.

In this sense, all trade and financial flows are organically connected—yet from a macro accounting perspective, the sum is always zero. One country’s deficit is another’s surplus. Understanding this identity is crucial to avoiding false narratives about “losing” or “gaining” in international trade.

Footnote: See Warren Mosler, “The Seven Deadly Innocent Frauds of Economic Policy”, for the original formulation of this principle.

8. Conclusion

Steve Keen’s criticisms of MMT rest on a misunderstanding of monetary sovereignty and the nature of international trade under floating exchange rates. Trade deficits do not destroy money; they create real gains and allow fiscal flexibility. Export-led growth strategies, like China’s, are political choices with internal costs. A better grasp of sectoral balances, policy sequencing, and currency sovereignty reveals that MMT does not deny financial instability or private debt dynamics—it simply places them in the correct macro framework.

MMT, far from being simplistic, offers the most coherent explanation of the monetary logic behind global trade and national prosperity.

Recommended Reading:

- Warren Mosler, The Seven Deadly Innocent Frauds of Economic Policy

- L. Randall Wray, Modern Money Theory

- Bill Mitchell, “There is no internal MMT rift on trade or development”

oooooo

“MMT is not a policy option; it’s a description of the economy” Political Economist Richard Murphy

oooooo

erabiltzaileari erantzuten

Description is not explanation. Explanation needs theory.

oooooo

It’s a description of monetary operations.

oooooo

Why does the government almost always spend in excess of taxes –i.e. run a budget deficit ?

A 1/

oooooo

Stephanie Kelton@StephanieKelton

erabiltzaileari erantzuten

This passage (from Galbraith) is key. Government deficits are necessary to prevent *private sector* balance sheets from deteriorating. 8/

oooooo

They probably even follow us on X.

Aipamena

Stephanie Kelton@StephanieKelton

oooooo

erabiltzaileari erantzuten

Yes, the Saudis are price setter and can do it for any reason they want. Wouldn’t be the first time they are targeting a euro price.

oooooo

”It is my guiding confession that I believe the greatest error in economics is in seeing the economy as a stable, immutable structure.” –John Kenneth Galbraith

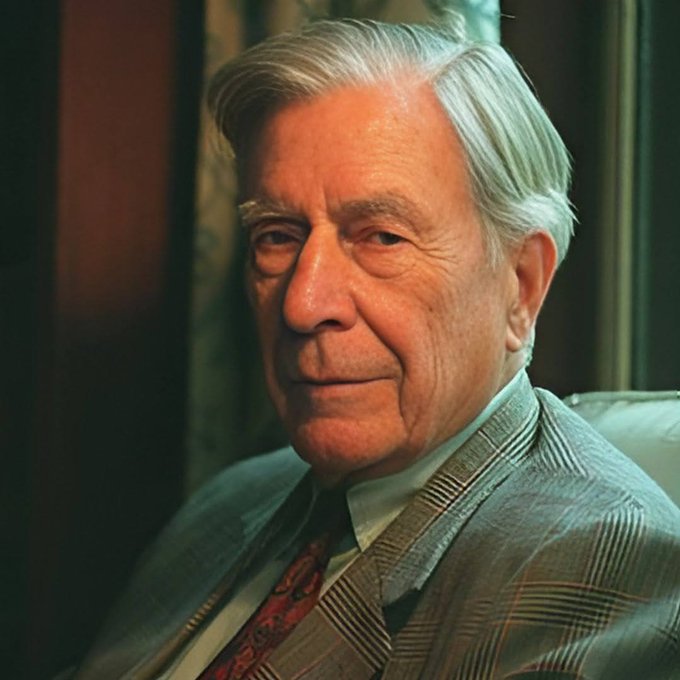

(Pinturak: Mikel Torka)