Errentaren desberdintasuna eta eskubitar mugimendu politikoak

eta

Trump-en neurri ekonomikoak, Tarifak direla eta

@tobararbulu # mmt@tobararbulu

Does rising income inequality explain the rising support for right-wing political movements?

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=62477

April 14, 2025

We know that after the Second World War, as nations embraced their major national policy statements (White Papers in many countries) to build their societies after the disruption of the War and the Great Depression, income inequality fell significantly. Since the 1970s, the post WW2 trend has been somewhat reversed in many (but not all) nations. The rising income inequality is particularly apparent in the Anglo advanced economies, with the US leading the way. In other nations, the trend is mixed, which suggests the link between rising income inequality and the rising support for right-wing political movements is less obvious than some commentators are suggesting. In fact, there is credible research that suggests the swing to right-wing political parties is not coming from the most precarious workers who appear to remain loyal to Leftist ideas. It is the next segment of workers up who have not yet been ravaged by globalisation but sense they are about to be who seem to have swung to the Right. In this blog post, I discuss some of these ideas and the research that is accompanying them.

It was no surprise that income inequality decreased after the peace came in the 1940s.

During the conflict, governments were able to levy relatively high taxes on the high income earners and wealthy.

For example, in the US the period 1937 to 1967 was labelled the – Great Compression – because government policy substantially reduced the spread in the wage distribution.

This ‘compression’ saw the highest marginal tax rate in the US reach 94 per cent in 1944 and remained at 91 per cent between 1945 and 1963.

The highest marginal rate since 2018 has been 37 per cent and in 2025 the cut off threshold “for individual single taxpayers” was $626,350 (Source).

In Australia, we saw a similar trend.

In 1950-51, the top marginal tax rate was 75 per cent to

In 2025, the highest rate is 45 per cent.

Stronger unions also played their part through their successful efforts to negotiate better pay and conditions for their members.

In the US, the Bureau of Labour Statistics publication – Union Members 2024 – shows ‘density’ rate (or coverage) which is the proportion of workers belonging to a union was 9.9 per cent in 2024.

The peak density was 25.7 per cent in 1953 (Source).

In Australia the same downward trend.

From 51 per cent in 1976 to 13.1 per cent in August 2024 (Source).

This 2011 study – The rise and decline of Australian unionism: a history of industrial

labour from the 1820s to 2010 – shows that the peak density was in 1948 when the proportion of workers in trade unions was 64.9 per cent.

It was still 62 per cent in 1954.

Similarly, as governments embarked on their nation-building exercises after WW2, they significantly increased their expenditure on social welfare as part of a commitment to a – Welfare state – and social democratic policy structure.

The generosity and scope of the social welfare support varied between nations and the work of Danish sociologist – Gøsta Esping-Andersen – helps us understand the different dimensions and reasons for these differences.

He distinguished between “liberal welfare states” (for example, US, Canada and Australia), “conservative, corporatist welfare states” (for example, Austria, Italy, France and Germany)”, and “Socialist (or social democratic) welfare states” (for example, the Scandinavian systems).

The reality is that since the 1970s, the generosity and scope of the support provided has been significantly retrenched in most nations.

The US-based Center on Budget and Policy Priorities – A Guide to Statistics on Historical Trends in Income Inequality (published December 11, 2024) – notes that:

The years from the end of World War II into the 1970s were ones of substantial economic growth and broadly shared prosperity …

Beginning in the 1970s, economic growth slowed and the income gap widened.

The 1970s marked the beginning of what we now call the neoliberal era which has become characterised by the sort of trends described above.

In the more recent period, we have also seen the splintering of political preferences among voters in many countries with the decline in support for the traditional mainstay parties on either side of the fence and increasing attention being placed on the more extreme, particularly extreme right parties.

I have been doing some research on the links between these trends – the socio-economic and the political – as part of a broader project on the poly crisis and degrowth.

One article I read recently was published in 2020 in the Journal of European Public Policy – The threat of social decline: income inequality and radical right support (library access needed) – which seeks to join together the rising income inequality and the increased popularity of “radical right wing parties … in Western democracies”.

There has not been much formal academic research seeking to examine whether the former (rising income inequality) is statistically linked and causal in the rise of right wing political support.

This article is an exception and uses the extensive dataset supplied as part of the – The International Social Survey Programme – which began in 1984 and produces “annual surveys on diverse topics relevant to social sciences” – my area of study.

The authors of the JEPP study extracted data from the ISSP database for 14 OECD countries spanning three decades.

I won’t discuss the methods and research design and you can consult the article if you are interested.

I found no major issues with the techniques and approach used.

Their motivation was informed by the extant research.

Some researchers have found that the radical right parties (RRPs) are becoming more popular because there is:

… a growing group of people who feel ‘left behind’ in the processes of globalisation and economic modernisation over the past several decades … [and] … Feeling threatened by increasing economic, cultural and political openness, they sympathise with RRPs that promise to put the nation and its people first.

The authors argue that we can adequately summarise this ‘left behind’ angst in a statistical setting using “income inequality”.

They note that:

… rising income inequality is an important indicator not only of the extent to which some groups have fallen behind compared to others, but also of the potential decline in society that people higher up in the social hierarchy could face.

Various sociological and psychological theories have been advanced to support this notion.

1. Relative deprivation – advanced by British sociologist – Garry Runciman – refers to “feelings or measures of economic, political, or social deprivation that are relative rather than absolute.”

The poorest people in advanced countries are probably better off in a material sense than the poorest in poor countries.

But relative to their society they advanced country poor feel poor.

J.K. Galbraith was very clear that the “relative differences in economic wealth are more important than absolute deprivation”.

There have been many studies linking increased relative deprivation to all manner of bad things – political instability, crime, etc.

If this was relevant in the current situation (rising RRPs) then the political support for these RRPs should be concentrated at the lower end of the income distribution.

2. The work of Norwegian economist Karl Ove Moene and US political scientist Michael Wallerstein on so-called risk theory suggests that “higher income inequality increases the perceived risk of economic and social decline. Individuals may worry about losing income or social status, leading to economic insecurity”.

This impacts on the “middle-income individuals” who are predicted to turn to RRPs because they “promise to address anxieties about decline by opposing globalisation and open labour markets” and shield them from major income loss.

3. The 2017 work by Allison and Jan Rovny – Outsiders at the ballot box: operationalizations and political consequences of the insider–outsider dualism – published in the Socio-Economic Review (library access required) – considers the ” emerging dualism between the so-called labor market ‘insiders and outsiders’ — two groups facing divergent levels of employment security and prospects” and the “electoral behaviour”.

They found that: (a) “outsiders are less likely to vote for major right parties than are insiders, and that outsiders are more likely to abstain from voting”; and (b) “occupation-based outsiders tend to support radical right parties, while status-based outsiders rather opt for radical left parties —a finding supported by the association between social risk and authoritarian preferences.”

This approach also suggests that it will be the middle-income workers who sense their position in the labour market is being undermined by global trends that will increasingly support the RRPs.

So overall, the research is somewhat mixed on how rising inequality might drive people to support and vote for these RRPs and which people will turn in this political direction.

The results of the author’s detailed econometric study investigating these ideas are summarised below:

1. “The probability for RRP support is significantly higher among the lower-middle income quintile compared to the bottom quintile.”

2. “Even the middle quintile tends to have a higher propensity of RRP support than the lowest income group”.

3. “In substantive terms, the effects of income are modest.”

4. The income “effects pale compared to education (3.32 percentage point difference between tertiary and non-tertiary educated respondents) or social class (4.24 percentage points difference between socio-cultural professionals and production workers).”

5. “rising income inequality increases the likelihood of RRP support and that this effect is most pronounced among individuals with high subjective social status and lower-middle incomes.”

6. “The long-run effect of inequality … is large in substantive terms”

7. “In increasingly unequal societies, therefore, anxieties about social decline seem to matter more for RRP choice than does actual deprivation.”

8. “in societies that have grown more unequal, the radical right has a substantial electoral potential among high-status individuals, not among those whose subjective status has declined the most”

9. “For the most deprived groups with lowest social status, income inequality is more plausibly associated with radical left party support, which promote strongly redistributive platforms”.

Those results resonated with the work I am doing at present.

For example, in countries like the US and Australia the measure of income inequality (Gini Coefficient) has risen substantially since the 1980s (and earlier for the US).

But in Germany, the rise has been modest and in the UK the Gini coefficient has fallen in recent years after rising substantially under Thatcher’s period of rule.

And in France, despite the rising popularity of Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National (RN) party the Gini has declined significantly.

A 2024 study by Ugo Palheta on who is driving Le Pen’s political support – Extrême droite: la résistible ascension – found that the neoliberal period has increased the job insecurity for low- and low-to-middle income earners, which white ants the stability conditions that social democracies were founded upon.

The political implications of these trends have occupied the minds of social scientists and the plausible narrative is that Le Pen’s popularity is a direct result of increasing job insecurity.

It is clear that the lower income workers have increasingly supported RN.

But the 2024 study finds nuances that are interesting.

It sought to differentiate the type of economic dislocation that is statistically related to support for RRPs.

The workers most damaged by increasing job insecurity and casualisation do not seem to be flocking to RN.

Indeed, RNs support among the working class is coming from segments that are more secure with higher pay, which the author suggests is a reflection of the need to differentiate their ambitions from migrants and the poor.

These workers also do not support Leftist notions of worker solidarity, which means there is a fundamental contradiction between the attacks on globalisation and the support for neoliberal individualism, which needs further analysis.

There are strong racist overtones (particularly against Muslims) in the cohort that supports RN.

The other interesting thing I am working on is the link between political parties in government and the shifts in income inequality.

A tentative conjecture is that it has been the traditional social democratic parties from the 1980s that have been captured by neoliberal perspectives and overseen the largest shifts in inequality, which were then consolidated or accentuated when the conservative side of politics followed the social democrats into power.

A related conjecture is that when in opposition, the traditional social democratic politicians ratify the policies that have worsened the income inequality and undermined the security of the working class.

Conclusion

Anyway, I hope some of those ideas and research outcomes are of interest.

They speak to the challenge facing Leftist political movements in arresting the tide towards RRPs.

They also suggest that even though politicians like Donald Trump (and the Tea Party mob before him) will undoubtedly worsen the lot of the most disadvantaged, it is highly likely he will continue to extract political support from these groups.

That phenomenon needs more analysis.

oooooo

Trump Administration appears to be kicking lots of own goals

(https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=62510)

April 28, 2025

Soon after the US President announced – Liberation Day tariffs – I wrote this blog post – US government is pinning its tariff hopes on some unlikely to be realised assumptions (April 7, 2025)1 – to help readers understand what logic there was, if any, in the decision by the American government to impose wide-ranging and seemingly random tariffs on the rest of the world. The only apparent logic was that his advisors thought that while the tariffs would variously increase the US dollar price on final goods and services available to US consumers via imports, the flood of global investment funds into US treasury bonds, as a result of the heightened global uncertainty would push the US dollar up and offset the tariff impacts on import prices, because all foreign goods would now be cheaper. We now have a few weeks of data available to see whether things are turning out as Trump and his advisors thought. The definitive answer to date is that the opposite trends are emerging which will see the burden of the tariffs borne by the US consumers and producers rather than the presumption of the Administration that the burden would be pushed onto the rest of the world, which would precipitate rapid change in the favour of the US. It seems at present that an ‘own goal’ is being kicked – and – probably a lot of them.

The substantive document that outlines the US government’s hopes post-tariff imposition was written Chair of Trump’s Council of Economic Advisors, Stephen Miran in November 2024 – A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System.

He wrote:

Tariffs provide revenue, and if offset by currency adjustments, present minimal inflationary or otherwise adverse side effects, consistent with the experience in 2018-2019. While currency offset can inhibit adjustments to trade flows, it suggests that tariffs are ultimately financed by the tariffed nation, whose real purchasing power and wealth decline, and that the revenue raised improves burden sharing for reserve asset provision.

Drawing on the experience in 2018-2019, during Trump’s first term, Miran wrote:

During his campaign, President Trump proposed to raise tariffs to 60% on China and 10% or higher on the rest of the world, and intertwined national security with international trade. Many argue that tariffs are highly inflationary and can cause significant economic and market volatility, but that need not be the case. Indeed, the 2018-2019 tariffs, a material increase in effective rates, passed with little discernible macroeconomic consequence. The dollar rose by almost the same amount as the effective tariff rate, nullifying much of the macroeconomic impact but resulting in significant revenue. Because Chinese consumers’ purchasing power declined with their weakening currency, China effectively paid for the tariff revenue.

Why might the offset mechanism occur?

Several factors are mentioned – none convincing.

He claims that the tariffs will boost US federal revenue and fiscal “deficit concerns are likely to be allayed”, which make US Treasury bonds more attractive.

He thinks Trump’s decisions to “aggressively deregulate portions of the economy” will boost economic growth and make US assets more attractive.

Global uncertainty also helps given the historical behaviour of global investors to move funds to US Treasury bonds in such times.

You may ask how a strengthening US dollar helps US manufacturers who are trying to sell into a competitive world market.

Miran acknowledged that should the exchange rate offset occur then “U.S. exporters now face a competitiveness challenge insofar as the dollar has become more costly for foreign importers”.

His solution?

An “aggressive deregulatory agenda, which helps make U.S. production more competitive”.

What does that mean?

It would have to include an attack on workers’ wages and conditions given the proportion of those items in total production costs.

He cited this article (April 29, 2024) – A Trillion-dollar Year – which was published by one of the never ending Right-wing propaganda ‘think’ tanks in the US which promotes, in their own words, “free-market solutions”.

The cited article was attacking the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) decision to protect people from PFAS in primary water supplies eand regulatory rules in the US, in general.

The author thought the costs to business of such protection were outrageous.

He also attacked the EPA for regulating to reduce “tailpipe emissions” in vehicles and to encourage EV use.

However, reducing “paperwork” won’t make the difference between US manufacturing being internationally competitive again versus not being so.

They would have to seriously cut wages.

Estimates in the past found that “China’s unit labour costs” (which combine wage costs with productivity estimates) were around 25 to 40 per cent of the US unit labour costs.

Further, while wages growth is accelerating in China as the emergence of the middle class substantiates, labour productivity growth is more rapid (by some) than it is in the US.

There was of course contradictions in the stance taken by Miran.

He also noted that the US President has “discussed adopting substantial changes to dollar policy. Sweeping tariffs and a shift away from strong dollar policy” because from “a trade perspective, the dollar is persistently overvalued, in large part because dollar assets function as the world’s reserve currency.”

If the US dollar, in fact, weakens at the same time the tariff is imposed then the aforementioned ‘offsets’ of the tariff impact on US prices through the exhange rate do not occur.

In fact, the exchange rate impact would heighten the tariff impact and worsen the situation faced by US consumers.

What has happened?

Things are not panning out as Miran suggested.

First, as part of the latest World Economic Indicators release, the IMF suggested (April 22, 2025) that – The Global Economy Enters a New Era.

They pointed to the tariff decisions as resetting the “global economic system under which most countries have operated for the last 80 years” which is creating “epistemic uncertainty and policy unpredictability” and the “attendant uncertainty will significantly slow global growth”.

For once I agree with the IMF.

The IMF has reduced its estimate of US growth from 2.8 per cent (published in January 2025) to 1.8 per cent in April.

According to their calculations, “tariffs account for 0.4 percentage point of that reduction.”

They also increased the “US inflation forecast by about 1 percentage point, up from 2 percent.”

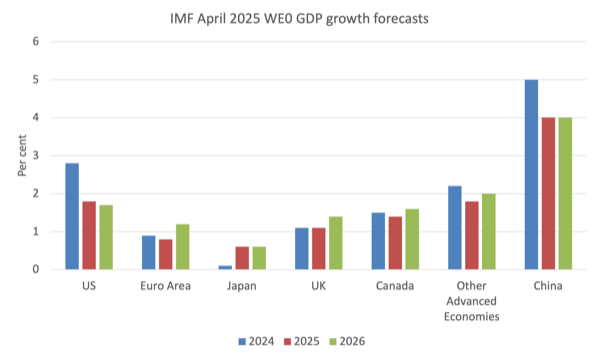

The following graph shows the latest growth forecasts from the IMF.

It is clear that they think the tariffs will damage US growth more than any other nation shown.

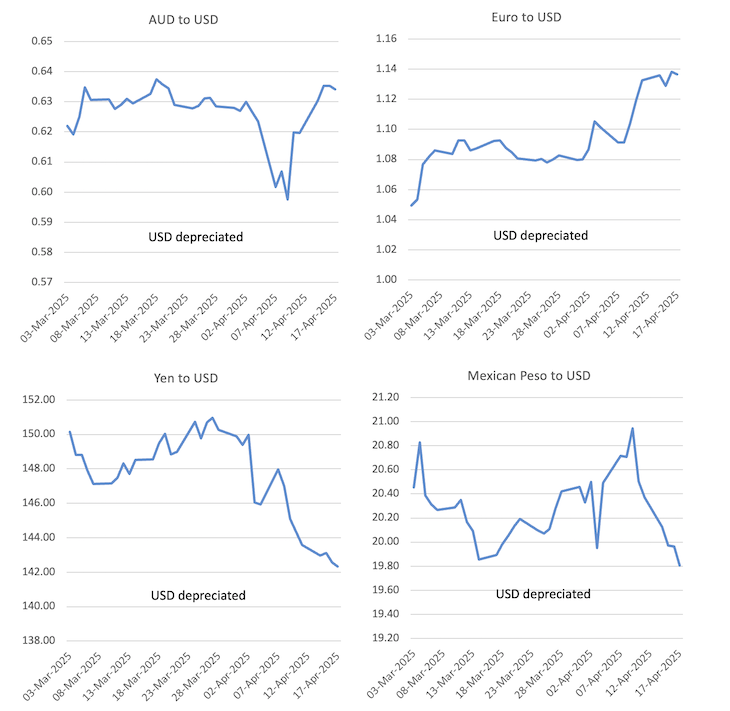

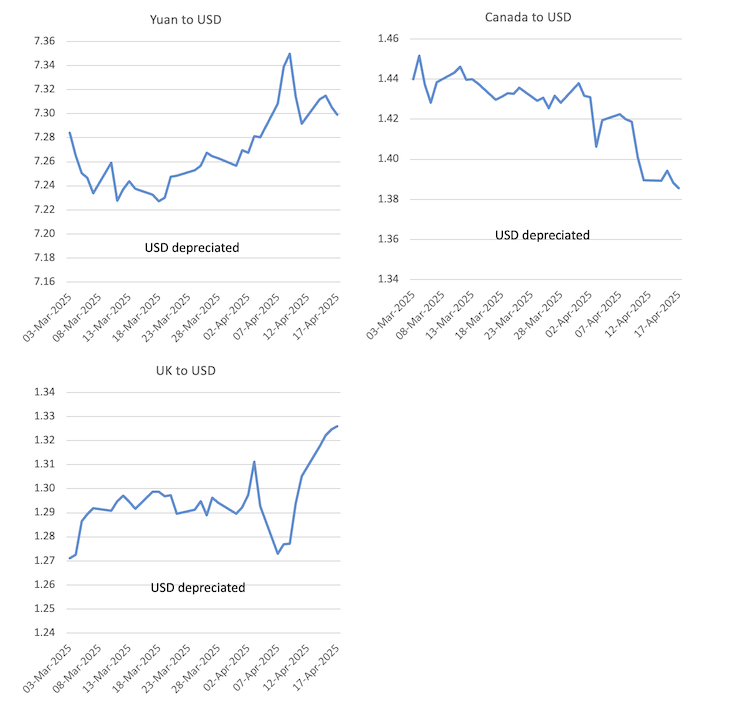

The movements in exchange rates have also been opposite to that required to offset the price impacts of the tariffs.

Here are some selected nations.

Note the quotation in the rates is not uniform, meaning that when the Australian dollar rises against the US dollar, it is an appreciation, whereas, for example, it is the opposite for the yen and peso.

However, in each of the cases shown, the USD has depreciated.

There has also been a lot of news lately about the way the bond markets are defying past history by moving investment funds out of US Treasury bonds despite rising uncertainty that is usually associated with the opposite movement of funds.

Last week, Reuters reported (April 24, 2025) – Japanese investors turned net buyers of overseas bonds last week – that:

U.S. Treasury yields have climbed this month, as bonds sold off, with hedge funds unwinding leveraged basis trades and overseas investors selling U.S. debt in apparent retaliation for tariffs and amid growing doubts about the safe-haven status of U.S. assets.

Japanese investors are the largest holders of U.S. Treasuries with approximately $1.13 trillion in holdings.

Meanwhile, overseas investors have been purchasing Japanese assets, driven by safe-haven demand and expectations that the Bank of Japan is likely to delay its interest rate hike in order to support the economy.

The UK Guardian article (April 9, 2025) = Dramatic sell-off of US government bonds as tariff war panic deepens – also reported similar trends.

It said: “US government bonds, traditionally seen as one of the world’s safest financial assets, are suffering a dramatic sell-off as Donald Trump’s escalation of his tariff war with China sends panic through all sectors of the financial markets.”

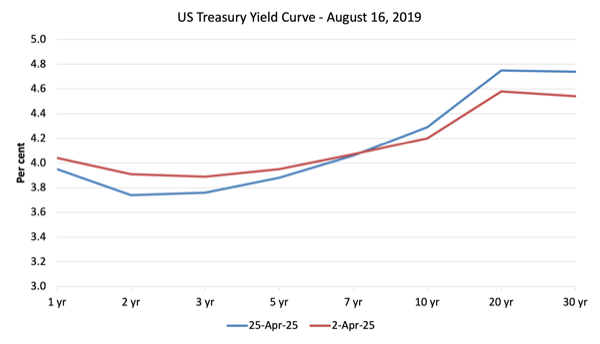

Here is the US yield curve for short- and long-term Treasury bonds on April 2, 2025 and April 25, 2025 (most recent available data).

Not only has there been an overall sell-off but also a switch into shorter-term bonds as the uncertainty increases.

The higher longer-term yields will attract funds back into the US, which we have seen in the last week or so.

But the reality is quite different to that predicted by the Chairman of Trump’s key economic advisory body the Council of Economic Advisors.

Conclusion

It is still only a month or so since the US liberated itself and these processes do not occur overnight.

So it could still work out the way Miran and Co hope.

But I doubt it.

It is looking very much like an own goal at this stage.

I obviously keep my eye on these trends and as they say ‘we will see’.

oooooo

Relearning Economics@RelearningEcon

”Coming up with the money is the easy part. The real challenge lies in managing your available resources—labor, equipment, technology, natural resources, and so on—so that inflation does not accelerate.”

-Stephanie Kelton

oooooo

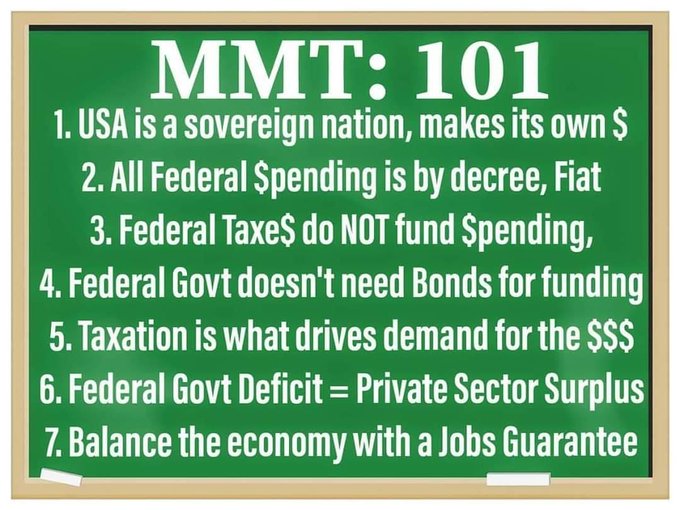

I appreciate the intent, but hate the use of the neoliberal lie that federal taxes fund spending.

Aipamena

MC Squared@mcsquared34

api. 23

oooooo

Relearning Economics@RelearningEcon