@tobararbulu # mmt@tobararbulu

Defizit gastua hasiberrientzat https://unibertsitatea.net/blogak/heterod

oooooo

Gonzalo Martinez Mosquera @gonzo_mm

Finally serious evidende that rate hikes work.

@wbmosler is clearly wrong

https://cnbc.com/2023/12/12/why-fed-rate-hikes-take-so-long-to-affect-the-economy.html

erabiltzaileari erantzuten

Finally! Now I can stop doing all this and get a life!

ooooooo

oooooo

oooooo

Wednesday’s blog post (20/12) is now posted (10:02 EAST) – The parallel universe in Japan continues and is delivering superior outcomes, while the rest look on clueless

oooooo

And here we go. Argentina has reached rock bottom with the new Zionist president

He managed to destroy the economy in 1 month. Promulgate a law that will completely sell off Argentina.

Argentina also announced that it is going to start printing money in denominations of 25 and 50 thousand pesos “for convenience” of payments.

I saw a horror movie in Zimbabwe that started out exactly the same way.

oooooo

oooooo

Mundu multipolarraz hitz bi

Multipolar Market@MultiPolarMarkt

EU nations unwilling to comply with their own sanctions?

There are many trade flows from the #EU to #Russia via Central Asia: mostly dual-use goods that are not subject to export controls, such as cars and spare parts

Not only Germany, but also Poland, Czechia and the Baltics are apparently not against such trade

oooooo

BRICS delakoaz, ortodoxiatik

Nobel Economist Joseph Stiglitz Hails New BRICS Bank Challenging U.S.-Do… https://youtu.be/fjyaGLFWWNA?si=0Pz-6FQDXk4EJFyn

Honen bidez:

Transkripzioa:

0:00

this is democracy Now democracynow.org

0:02

the Warren peace report I’m Amy Goodman

0:04

with Juan Gonzalez well a group of five

0:06

countries have launched their own

0:08

Development Bank to challenge the United

0:10

States dominated World Bank and

0:12

international monetary fund leaders from

0:15

the so-called bricks countries Brazil

0:17

Russia India China and South Africa

0:20

unveiled the new development bank at a

0:22

summit in Brazil the bank will be

0:25

headquartered in Shanghai Chinese

0:27

president zi Jinping said the agreement

0:30

would have far-reaching benefits for

0:31

bricks members and other developing

0:36

nations through the concerted effort

0:39

from all sides we have managed to reach

0:41

a consensus in the creation of the

0:43

bricks Development Bank today this is

0:46

the result of the significant

0:48

implications and far reach of bricks

0:51

cooperation and is therefore the

0:53

political will of brics Nations for

0:55

common development this will not only

0:57

help increase the voice of brics nation

1:00

in terms of international finance but

1:03

more importantly will bring benefits to

1:05

all the people in the bricks countries

1:08

and for all peoples in developing

1:10

countries that was Chinese president XI

1:13

Jin ping together bricks countries

1:16

account for 25% of global GDP and 40% of

1:19

the world’s population for more we

1:20

joined Now by Joseph stiglet the Nobel

1:22

prizewinning Economist professor at

1:24

Columbia University author of numerous

1:26

books his new book is called creating a

1:28

learning Society a new approach to

1:30

growth development and social progress

1:33

we welcome you to democracy Now talk

1:35

about the significance of this Bank oh

1:37

it’s very very important uh in many ways

1:41

first the need globally for more

1:45

investment in the developing countries

1:47

especially is in the order magnitude of

1:49

trillions couple trillion dollars a year

1:52

and the existing institutions just don’t

1:55

have enough resources they have enough

1:56

for 2 3 4% so this is adding to the flow

2:01

of money that will go to finance

2:03

infrastructure adaptation to climate

2:05

change all the needs that are so evident

2:08

in the poorest countries secondly it

2:11

reflects a fundamental change in global

2:14

economic and political power that uh one

2:18

of the ideas behind uh this is that the

2:22

bricks countries today are richer than

2:25

the advanced countries were when the

2:27

World Bank and the and IMF were founded

2:30

we’re in a different

2:32

world at the same time the world hasn’t

2:36

kept up the old institutions have not

2:39

kept up you know the

2:41

G20 talked about and agreed on a change

2:45

in the governments of the IMF and the

2:47

World Bank which were set back in 1944

2:49

there have been some

2:51

revisions but the US Congress refuses

2:55

to follow along with with the agreement

2:58

the administration

3:00

failed to go along with what was widely

3:03

understood as the basic notion that you

3:06

know in the 20% the heads of these

3:09

institutions should be chosen on the bar

3:11

on the basis of Merit not just because

3:13

you an American and yet us effectively

3:17

renaged on that agreement so this new

3:20

institution reflects the disparity and

3:24

the the Democratic deficiency in the

3:27

global goverance and is trying to to

3:29

restart to to rethink that finally there

3:33

have been a lot of other changes in the

3:35

global economy uh and the new

3:37

institution

3:39

reflects uh the broader set of mandates

3:42

the new concerns the new sex of instit

3:45

instruments that can be used the new

3:47

financial instruments um and the broader

3:51

governance the realizing the

3:54

deficiencies in the old system of

3:56

governance hopefully this new

3:59

Institution will spur the existing

4:02

institutions to

4:04

reform and uh that’s will you know it’s

4:07

not just competition it’s it’s really

4:10

trying to get more resources to the

4:13

developing countries in ways that are

4:15

consistent with their interest and and

4:17

needs and the importance of countries

4:21

like China which obviously has huge uh

4:24

uh monetary reserves and Brazil which

4:26

had developed its own Development Bank

4:28

now for several years they’re being key

4:31

players in uh in this new uh Financial

4:34

organization very much and that

4:35

illustrates as you say a couple

4:36

interesting points uh China has reserves

4:40

in excess of3

4:41

trillion so one of the things is that it

4:45

needs to use those reserves better than

4:49

just putting them into uh US Treasury

4:52

pills you know my my colleagues in in

4:56

China say that’s like putting meat in a

4:59

ref refrigerator and then pulling out

5:01

the plug because the real value of the

5:03

money putting us treasury bills is

5:05

declining so they said we need better

5:07

uses for those funds certainly better

5:10

uses than using those funds to build say

5:13

shotty homes in the middle of the Nevada

5:15

desert you know they’re real social

5:17

needs and those funds haven’t been used

5:19

for those purposes uh at the same time

5:23

Brazil has uh the bnds is a huge

5:28

Development Bank big BG ger than the

5:29

World Bank people don’t realize this but

5:32

Brazil has actually shown how a single

5:35

country can create a very effective

5:38

Development Bank so there’s a learning

5:41

going on and this notion of how you

5:45

create an effective Development Bank

5:47

that actually promotes real development

5:50

without all the conditionality and all

5:53

the the trappings around the old

5:56

institutions is is going to be an

5:58

important part of the contribution that

6:00

Brazil is going to make and how has that

6:01

bank function differently let’s say than

6:03

other development banks in the uh in in

6:05

the north well we don’t know yet because

6:08

it it it it’s just getting started the

6:11

agreement it’s been several years

6:14

underway uh the discussions began about

6:16

three years ago and then they made a

6:19

commitment and then they you know

6:20

they’ve been working on it very uh

6:23

steadily uh what was big about this

6:26

agreement was that there was a little

6:28

worry that there would be be conflicts

6:31

of the interest you know everybody

6:32

wanted the headquarters the president um

6:36

would there be enough political cohesion

6:40

solidarity to um make a

6:44

deal answer was there was so what it was

6:48

really saying is that in spite of all

6:51

the differences the Emerging Markets can

6:54

work together in a way more effectively

6:57

than some of the advanced countries can

6:58

work together

oooooo

Europa-z

Jacques Delors destroyed the European Left

The French Socialist enabled the populist Right

(https://unherd.com/2023/12/jacques-delors-destroyed-the-european-left/)

BY Thomas Fazi

December 29, 2023

There’s a story European progressives like to tell themselves: that, after the horrors of the Second World War, their governments struck a quasi-utopian compromise between capitalism and socialism — only for it to be corrupted by the import of the cutthroat capitalism that defined Reagan’s neoliberal counterrevolution in the early Eighties.

It’s a comforting fable, designed to excuse their own failures. It is, however, completely untrue. Neoliberalism wasn’t exported to Europe from across the Atlantic (or from across the Channel, for that matter). It was a largely homegrown affair — one that was, in fact, spearheaded by European Socialists, and by one Socialist in particular: Jacques Delors, President of the European Commission from 1985 to 1995, who died this week.

To understand this tragedy, we need not return to 1945, but 1981. In May, the Socialist François Mitterrand was elected France’s president, after more than two decades of the Left being excluded from office. He went on to form a government that also included Communist ministers for the first time since 1947, prompting a widespread belief that France was headed for a radical break with capitalism.

At the time, such a notion was not inconceivable. Most European governments still firmly believed in the importance of economic dirigisme and the need for capital controls and regulated financial markets, which presupposed a high degree of economic sovereignty. Nowhere was this truer than in France: the French had always been particularly reluctant to agree to any supranational authority — a consistent position that had hampered progress towards an economic and monetary union. In general, there was still the belief that individual nations had the power to shape their own economic and political destinies — and even to challenge the capitalist system itself.

Nothing exemplifies this better than Mitterrand’s victory in the spring of 1981. The new president’s policy agenda embodied an ambitious reform programme of Keynesian economic reflation and redistribution. It also proposed extensive nationalisations of France’s industrial conglomerates. By implementing this platform, Mitterrand claimed, his government would precipitate a “rupture” with capitalism, and lay the foundations for a “French road to socialism”. It’s easy to see why this represented a moment of immense hope not just for the French Left, but for the entire European Left — of the kind not witnessed since.

Soon after the Mitterrand experiment began, however, it started to unravel. As a reaction to the Socialists’ ambitious plan for economic reform, capital started to flee France almost immediately. Despite the imposition of draconian capital controls, the government was unable to halt the flight.

This created a downward pressure on the franc (further exacerbated by the post-1979 global interest rate hikes), threatening France’s membership in the European Monetary System (EMS) — the system of semi-fixed exchange rates created in 1979. Under the EMS, the central banks of participating states had little choice but to shadow the Bundesbank’s restrictive monetary policy. Yet this was incompatible with Mitterrand’s reflationary programme — and Mitterrand found himself in a position where a decision had to be made about whether to leave the EMS or abandon his progressive agenda. Regrettably, he chose the latter path.

And so, in the spring of 1983, Mitterrand and the Socialists drastically reversed course, in what came to be known as the tournant de la rigueur (turn to austerity): rather than growth and employment, the emphasis would now be on price stability, fiscal restraint and business-friendly policies. A crucial aspect of this was the gradual rollback of virtually all capital controls and restrictions on financial transactions. And who was the main architect of this shift? Mitterrand’s finance minister, Jacques Delors.

The effects of this U-turn cannot be overestimated. Mitterrand’s victory in 1981 had inspired the widespread belief that a break with capitalism — at least in its extreme form — was still possible. Yet two years later, the French Socialists had succeeded in “proving” the exact opposite: that globalisation was an inescapable reality. Even though there were alternatives available to Mitterrand (such as leaving the EMS and floating the franc), the conclusion most people drew was that the “Keynesian road to socialism” had failed. Capital had won.

To make matters worse, the French Socialists, after having embraced neoliberalism at home, then proceeded to export their newfound views — on everything from capital movements to monetary integration — to the rest of Europe. Here, Delors was also central. “National sovereignty no longer means very much, or has much scope in the modern world economy,” he said. “A high degree of supranationality is essential.” This was a radical departure from France’s traditional souverainiste stance, which had already been seriously compromised by France’s decision to join the EMS, under which, as noted, the country was effectively forced to subjugate its own monetary-fiscal policy independence to the Bundesbank’s monetary policy.

For all of France’s historical concerns about supranational (that is, “European”) encroachment on its sovereignty on the one hand, and German hegemony on the other, few missed the irony of it being the Socialists who gave up that freedom — and to Germany of all nations. But by the late Seventies, French politicians on both sides of the political divide had come to accept that maintaining France’s status required them to remain firmly “in Europe” — that is, in the EMS — which in turn entailed adopting a low-inflation, stable-currency policy.

This brought about a distinct shift in attitudes among the Socialists towards Europe — a mood that Delors summed up in October 1983: “Our only choice is between a united Europe and decline.” As Rawi E. Abdelal, professor of business administration at Harvard Business School, noted: ‘To the extent that the French Left continued to hope for socialist transformation, its members could see Europe as the only arena in which socialist goals could be achieved.” The problem was that, by 1983, they had little to offer in terms of a Europe-wide progressive alternative, since they had accepted the notion that social-political objectives should be subjugated to “price stability”.

And so, two years later, France strongly supported Delors’s nomination to the post of President of the European Commission — a position he would go on to hold for a decade, serving for three terms, longer than any other holder of the office. It is no exaggeration to say the Delors presidency was groundbreaking, giving the European integration process a momentum that had been lacking in the preceding decade. It is also the period in which the foundations of monetary union, and more generally of neoliberal Europe, were laid down — a development in which Delors, and the French Socialists in general, played a key role.

Their logic was the following: given that, within the EMS, the Bundesbank effectively set the interest rates for all participating states, and that leaving the EMS wasn’t considered an option, the French became increasingly convinced that there was only one way to preserve a low-inflation fixed exchange rate system while also wrestling control of monetary policy away from Germany: to push for a full European monetary union. For Delors, creating a single European currency became an utmost priority, and he set out to persuade his reluctant fellow European policymakers to embrace the idea. The first step was the signing of the Single European Act, in 1986, which set the objective of establishing a single market by 1992. Delors also proceeded to export France’s new views on capital movements to the rest of Europe, by pushing for the full liberalisation of capital flows across the continent — paving the way for a monetary union.

This brings the historical importance of the French Left’s neoliberal turn into stark relief: if the French hadn’t embraced financial liberalisation at the domestic level, they never would have offered their support for an integrated European financial market — and a monetary union would likely never have seen the light of day.

The Commission’s proposals were initially met with fierce resistance from a number of governments. But by the late Eighties, Delors had succeeded in radically changing Europe’s approach to capital controls — and in getting EU member countries to introduce full capital mobility by 1992, effectively making the free movement of capital a central tenet of the emerging European single market. This was a binding obligation not only among EU members but also between members and third countries.

In effect, Delors had succeeded in pushing Europe to fully embrace the “Paris consensus”, the European equivalent of the Washington consensus. The consequence of this was a European financial system that was, in principle, the most liberal the world had ever known. In this sense, the Europeans, far from being passive recipients of the free-market policies being concocted in Washington, actually preceded the Americans in embracing neoliberal globalisation, and promoting the spread of global capital.

This also profoundly influenced the construction of the monetary union. In short, Delors succeeded in convincing European governments that, by joining the EMS and liberalising capital flows, they had effectively already lost much of their economic sovereignty; they therefore had little choice but to embrace monetary integration as a way to regain some sovereignty at the supranational level, by “having a say” in Europe’s collective monetary policy. It was a shrewd argument, but a fallacious one: as history would show, by ceding their monetary policy to a supranational central bank, European governments simply ended up losing what little sovereignty they had left.

However, Delors was aided by the fact that, by the early Nineties, even the German establishment had come round to the idea of a monetary union — and indeed, national elites in most European countries had come round to the notion of a supranational central bank, fully immune to democratic pressures, as a useful way to insulate economic policy from popular contestation. By 1989, the Delors Committee had published its hugely influential Delors Report, which essentially acted as a blueprint for the construction of monetary union in the coming years.

The final act of this democratic tragedy came three years later with the Maastricht Treaty. This didn’t only establish a timeline for the establishment of monetary union (in line with the Delors Report), but also created a de facto economic constitution that embedded neoliberalism into the very fabric of the European Union. By the time the Delors Commission came to an end, in 1995, much of the groundwork for the techno-authoritarian and anti-democratic juggernaut that the EU would later become was laid — and, to a large degree, we have Delors, a French Socialist, to thank for that.

Ironically, this didn’t just lead to the demolishing of the Left’s cherished European social model, to the benefit of financial-corporate interests (and, of course, Germany), but it also paved the way to the demise of the European socialist Left — and to the rise of the populist Right. More than anyone else, it is the latter who, today, should pay tribute to Delors.

oooooo

Scott Ritter Show Ep. 58

Bideoa: https://rumble.com/v42bl96-scott-ritter-show-ep.-58.html

Scott Ritter Show Ep. 58

Podcasts Trending News Putin Zelensky Russia Ukraine Israel Hamas Netanyahu

On episode 58 of the show we are joined by Henry Sardaryan, Dean of the Faculty of Governance and Politics of the Moscow State Institute of International Relations of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MGIMO), Doctor of Political Sciences, Member of the Public Chamber of the Russian Federation and an Academician of the Military Academy of the Russian Federation. Additionally, on the recommendation of the Russian Foreign Ministry and with the support of UN Secretary General Guterres, Sardaryan was elected representative of the Russian Federation for the UN Expert Committee on Public Administration.

oooooo

The Eurocrats’ secret weapon

Twenty-five years on, the euro has handed them victory

(https://unherd.com/2024/01/the-eurocrats-secret-weapon/)

BY Thomas Fazi

.A protest outside the ECB (DANIEL ROLAND/AFP via Getty Images)

Thomas Fazi is an UnHerd columnist and translator. His latest book is The Covid Consensus, co-authored with Toby Green.

January 3, 2024

On January 1, as the European Union ushered in another year of economic chaos and not-so-distant wars, no one was in the mood to celebrate the euro’s 25th birthday. No one, that is, but the Eurocrats.

As always, the EU’s top brass waxed lyrical about the single currency, but this year their musings sounded more delusional than ever. In an opinion piece published across the eurozone, the presidents of the European Central Bank, Commission, Council, Eurogroup and Parliament praised the euro for giving the EU “stability”, “growth”, “jobs”, “unity” and even “greater sovereignty”, and for being an overall “success”.

Such self-congratulatory back-slapping is common among Eurocrats. In 2016, for example, as Europe was still reeling from the disastrous consequences of the euro crisis, Jean-Claude Juncker, then President of the Commission, said that the euro brings “huge” though “often invisible economic benefits”. This year’s statement, however, had a particularly Orwellian feel to it. The euro has not brought any of those things to Europe: the EU today is weaker, more fractured and less “sovereign” than it was 25 years ago.

Since 2008, the euro area has essentially been stagnating — and its overall long-term growth trend has been negative. This has led to a dramatic divergence between its economic fortunes and those of the US: adjusted for differences in the cost of living, the latter’s economy was only 15% larger than the euro area’s economy in 2008; it is now 31% larger. Today, the euro’s share of global currency reserves is significantly lower than its predecessors — the Deutsche Mark, French franc and ECU — in the Eighties.

But this is far from the only result of the euro’s failure. When it was introduced, it was hoped that the single currency’s “culture of stability” would narrow the difference in terms of its members’ economic performance. In effect, as the IMF has noted, the opposite has happened: “the envisaged adjustment mechanisms under monetary union have been insufficient to support convergence, and have in some cases contributed to divergence”. Added to this, exports between euro nations as a percentage of total eurozone exports have been on a downward trend since the mid-2000s.

It seems clear, then, that the introduction of the euro was a mistake — but only if we take its proponents’ stated intentions at face value. For it is important to understand that the euro was always as much a political project as an economic one. And, from that standpoint, it has been an extraordinary success.

There’s a reason the foundations of the monetary union were only laid in the early Nineties, even though the idea had been around since 1970. That year, the first report examining the feasibility of monetary union was published. Known as the Werner Report, it stressed that, in addition to the creation of a European central bank as the issuer of the new single currency, “transfers of responsibility from the national to the Community plane will be essential” for the conduct of economic policy.

Seven years later, the MacDougall Report reinforced the need for a sizeable EU budget — of 5% or more of EU GDP — to underpin any European monetary union, with responsibility for it handed to a European Parliament. Given the reluctance of member states to move towards a fully-fledged monetary and fiscal union, which would have involved significant transfers between countries, the plans for monetary union floundered for another decade. However, new life was then breathed into the euro project in the late Eighties and early Nineties — not because the economics of the project had improved, but because the politics around the idea of monetary union had changed, especially at the level of Franco-German relations.

The official story is that the French, who had always been particularly reluctant to agree to any supranational authority, came round to the idea of a monetary union in the wake of German reunification, as a way of “shackling” German power. Germany, meanwhile, relinquished its much-loved national currency, the symbol of its post-war economic achievement, in order to quell concerns about its growing hegemony.

The reality, in fact, was more complicated. It is true that France hoped that monetary integration would constrain Germany. But France was also influenced by domestic developments — in particular the French Socialists’ neoliberal turn in the early Eighties, under Mitterrand. This led it to embrace the idea that “national sovereignty no longer means very much” and that “a high degree of supranationality is essential”, as Mitterrand’s finance minister, Jacques Delors, put it — an idea that Delors would then export to the rest of Europe during in his role as President of the European Commission from 1985 to 1995.

As for Germany, the notion that the country reluctantly accepted to have the euro foisted upon itself, in exchange for its European partners’ acceptance of reunification, is largely a myth. German elites were perfectly aware that the eurozone would give an immense boost to Germany’s export-led mercantilist strategy, by ensuring a significantly lower exchange rate with the euro than it would have had with the Deutsche Mark, even in the face of persistent trade surpluses. In other words, the German elites viewed the euro as a way of reasserting their hegemony over Europe — the exact opposite of what the French were hoping to achieve.

For a while at least, history would prove the Germans right. They seized the opportunity to ensure that the future monetary union would be functional to German interests, partly by getting other member states to agree to the creation of a fully independent central bank — that is, fully insulated from a democratically elected polity — with the sole mandate of ensuring price stability. No wonder Helmut Kohl, Germany’s Chancellor, admitted to pushing through the euro “like a dictator” in face of a reluctant public, while Theo Waigel, his finance minister, boasted about “bringing the Mark in Europe”.

Why did other countries agree to join a monetary union destined to boost the German economy at the expense of other less export-dependent economies, such as Italy? There were certainly ideological elements at play, such as the rise of monetarism, but, as with France, the reasons were mostly political rather than economic. By the early Nineties, national elites in most European countries had come to view the euro as a “Trojan horse” with which to push through neoliberal policies for which there was little political support, by engaging in what Kevin Featherstone has called a “‘blameshift’ towards the ‘EU’”.

Moreover, by explicitly prohibiting the ECB from acting as lender of last resort and forcing states to rely solely on loans from the financial markets for their financing needs, the idea was that representative democratic institutions would be subject to the supposed “discipline” of the markets. Angela Merkel coined a rather ominous term for such a system: “market-conforming democracy”.

In short, the euro saw the light of day because national elites came to embrace the idea for different but convergent reasons: in some cases (such as Germany), it was a matter of gaining an economic advantage at the expense of other countries; in others (Italy, for example), it was a matter of gaining an advantage at the expense of domestic actors, even if that cost economic growth.

The result was an extremely dysfunctional monetary union. And when the financial crisis hit, and a series of credit-led economic booms — fuelled by massive capital flows from Europe’s core to the periphery — went bust, the implications of its structure hit home. Those members in a slump could not devalue. Since they could not print their own money, and because the central bank was unwilling to act as lender of last resort, they risked sovereign default, or national insolvency, as they came under attack from financial markets. Essentially, the euro was their downfall.

Yet, by late 2010, European elites — the Germans, in particular — had rewritten history. The financial crisis was not the fault of an out-of-control system exacerbated by the dysfunctional nature of the monetary union; it was, they claimed, the fault of excessive government debt inflated by countries that had “lived well beyond their means”. The fact that most euro countries had registered primary fiscal surpluses in years leading up to the financial crisis, and that public debts had exploded only in the latter’s aftermath as a result of the massive bank bail-outs, was conveniently brushed aside. There was only one possible “cure”, Europe’s leaders proclaimed: austerity. The leading proponent of this theory was Germany’s ultra-hawkish finance minister, Wolfgang Schäuble, who died last week.

The imposition of such harsh fiscal austerity measures across the eurozone didn’t just raise unemployment, erode social welfare, push populations to the brink of poverty and create a genuine humanitarian emergency — it also completely failed to achieve the stated aims of kickstarting growth and reducing debt-to-GDP ratios. Instead, it drove economies into recession and increased debt-to-GDP ratios. Meanwhile, democratic norms were dramatically upended, as entire countries were essentially put into “controlled administration”. The result was a “lost decade” of stagnation and permacrisis that led to a profound divide between the eurozone’s north and south, and brought the monetary union to the brink.

This wasn’t simply the “automatic” outcome of the defective architecture of the monetary union. Rather, the European “sovereign debt crisis” of 2009-2012 was largely “engineered” by the ECB (and Germany) to impose a new order on the continent. Indeed, former ECB president Jean-Claude Trichet made no secret of the fact that its refusal to support public bond markets in the first phase of the financial crisis was aimed at pressuring eurozone governments into consolidating their budgets and implementing “structural reforms”. But the ECB then went further, resorting to various forms of financial and monetary blackmail — most notably in Ireland, Greece and Italy — with the aim of coercing governments to comply with the overall political-economic agenda of the EU.

In this sense, we could say that the euro crisis was both an economic disaster and a political success for Europe’s financial-political elites. After all, it allowed them to radically restructure and re-engineer European societies and economies along lines more favourable to capital, while creating one of the single biggest upward transfers of wealth in history — all in the name of the allegedly inescapable realities of the euro.

Since then, not much has changed in terms of the inner workings of the monetary union. Even the temporary suspension of the EU’s fiscal rules during the pandemic is in the process of being curtailed; a rehashed but fundamentally unchanged version of the EU’s fiscal framework is set to come back into force this year, spelling the return of austerity to the continent. That Germany has fallen from grace in the process, going from unchallenged European hegemon to American vassal-in-chief, is one of the great ironies of the past decade.

Nonetheless, when European elites say that the euro has been a success, they are unwittingly revealing a truth. From their perspective, it undoubtedly has; and their greatest success has arguably been to convince everyone that there is no alternative. To paraphrase Mark Fisher, it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of the euro.

oooooo

What “debt?” #LearnMMT

urt. 3

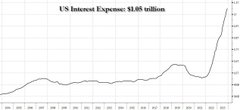

US national debt by just passed $34 trillion and only the interest expense is now at $1.1 trillion. – There is no way out of this anymore https://usdebtclock.org

oooooo

Ashish Barua आशिष बरूआ #MMT From INDIA

@barua_ashish

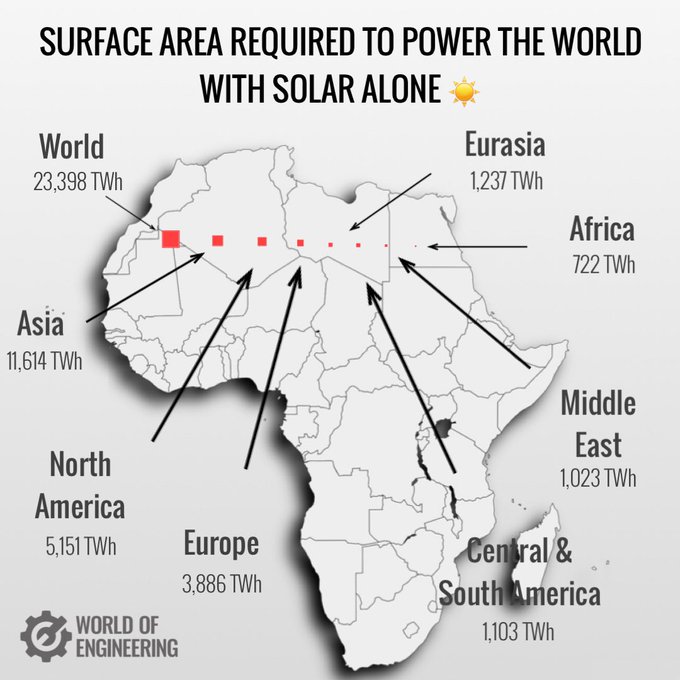

The world can switch towards green energy without relying on #FossilFuels. #Solarenergy is perfectly capable of electrifying industry. The world has enough real resources.

urt. 3

Folks get confused about solar. It is perfectly capable of electrifying industry. And new solutions fo storage are forth coming all the time, from Energy Vaults to Water Storage to using Photothermal as part of the mix. And no one is saying we will need to rely on solar alone. Solar, Hydro, Wind, Thermal, Nuclear and other tools can all be part of a clean mix of energy.

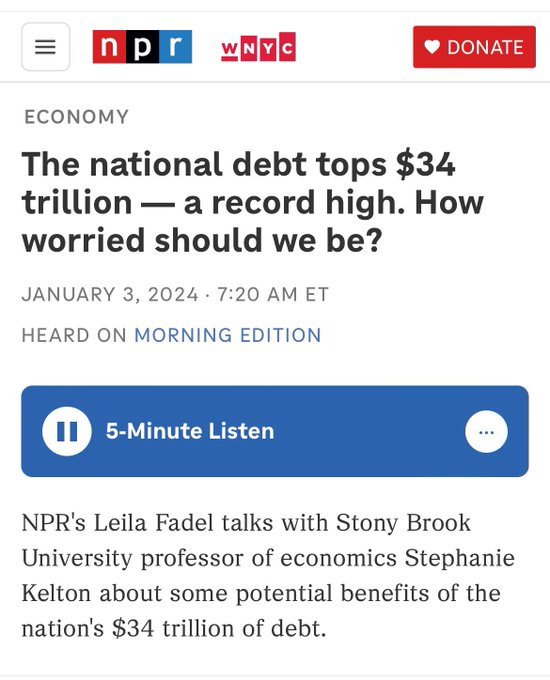

From the dispassionate perspective of a news organization, “Public Debt Hitting A Big Record Round Number” is an inexhaustible source of material. The alternative is doing actual work to find a real story, and doing actual work is a pain in the butt.

Aipamena

Stephanie Kelton@StephanieKelton

urt. 3

@StephanieKelton erabiltzaileari erantzuten

I had a chance to comment on the latest headline-grabbing milestone earlier today. You can listen

The gov’s *deficit* spending itself creates the reserve balances that pay for the Tsy secs. The public debt is the $ spent by gov that haven’t yet been used to pay taxes. The $ to pay taxes and buy Tsy secs are the reserve balances created by the gov’s deficit spending.oOooooo

Wall Street’s War on Workers w/ @les_leopold. Join us for the video premiere tonight at 7 pm ET! #WallSt #Workers #Layoffs #Austerity

Bideoa: https://youtu.be/4aBiOac3glQ

From youtube.com

oooooo

Job Guarantee. Lan bermea

pavlina-tcherneva.net

The Case for a Job Guarantee

Frequently Asked Questions

About the Job Guarantee

1. How many people will the program employ?

2. How much will a JG job pay?

3. How much will the JG program cost?

4. Who will pay for the program?

5. Who will administer the program?

6. Wouldn’t the JG create massive new administration and bureaucracy?

7. Where will the jobs be?

8. What types of jobs will the JG workers do?

8-a. Can you provide some specific examples of JG jobs?

9. Wouldn’t the JG displace existing forms of public sector work?

10. How do we distinguish between regular public sector work and JG jobs?

11. Can we place JG workers with private contractors?

12. Why is the JG wage the effective minimum wage and labor standard for the economy?

13. Why do you say that this program is a better countercyclical stabilizer?

14. Why is the JG sometimes called buffer stock employment?

15. Why do you say that the JG has a superior anti-inflationary mechanism?

15-a. Does the JG cause inflation?

16. Is the JG a substitute for other fiscal or monetary policies?

17. Why not simply add work requirements to existing benefits programs like TANF, SNAP, or, as has been recently proposed, Medicaid? Why the JG?

18. Isn’t the JG just a workfare program?

19. Aren’t JG jobs just “make work”?

20. You have proposed a nonprofit/social entrepreneurial model for the JG (Tcherneva 2012, 2014). How can you be sure that enough projects will be proposed by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and social-entrepreneurial ventures (SEVs) to provide work for all?

21. Who is the employer of record?

22. If an NGO hires JG workers along with other NGO workers, who decides whose wages will be paid by the government?

23. What if the JG workers are doing very important work and it is unwise to let them go?

24. What if people do not wish to exit the JG program?

25. The needs of the structurally vs. cyclically unemployed are different. Can the JG really create jobs quickly for all?

26. Can JG workers be fired?

27. How do you judge program success?

28. If you can fire people from the program, then the threat of unemployment is not eliminated?

29. If you can fire people from the program, then it is not a true JG, is it?

30. What about people who do not want to work in the program?

31. But isn’t this program prone to inefficiency, corruption, and abuse?

32. Won’t the JG increase the size of government?

33. People will just get stuck in the JG program and will never leave.

34. Are you saying that the government should employ everyone?

35. Didn’t the former Soviet bloc have a JG? Isn’t that what you are proposing?

36. Seems like a daunting task. Can we phase it in and how?

37. Are there real-world programs we can study?

38. Wouldn’t the JG workers crowd out many volunteer opportunities?

39. Wouldn’t JG workers be stigmatized?

40. Will undocumented immigrants be eligible for the program?

41. By allowing nonprofits to submit grant proposals for JG projects to the government, aren’t you advocating for providing a giant subsidy to religious institutions?

42. Why don’t we just give people cash assistance instead?

43. Isn’t universal basic income (UBI) a better program?

44. You are just accepting and reinforcing the current morality of work. Shouldn’t we be moving to a post-work society, a world of leisure?

45. Does the government have the capacity to manage such a large workforce?

46. Doesn’t technology make jobs obsolete?

47. Isn’t Kalecki’s (1943) “Political Aspects of Full Employment” the definitive statement on why the JG is not feasible?

48. Will my taxes go up to fund this program?

49. Is there one specific feature of the program that you wish to highlight?

50. Makes perfect sense. Why haven’t we passed a JG already?

Job Guarantee

Distribution of average income

BOOK

The Case for a Job Guarantee (forthcoming 2020, available for preorder and here), Polity Press

OVERVIEW

1. THE JOB GUARANTEE: WHAT, WHY, HOW (video1 14min):

2. A PROPOSAL FOR THE UNITED STATES (video 16min)

3. JOBS, DESIGN, AND IMPLEMENTATION (pdf, including FAQ)

WHY THE JG IS THE NEW FISCAL POLICY APPROACH WE NEED

1. Reorienting Fiscal Policy: A Bottom Up Approach {pdf}Full Employment: the Road Not Taken {pdf}

2. Full Employment: the Road Not Taken {pdf}

2. What is MMT and Why is the Job Guarantee Crucial to the Project

WHY IT IS SUPERIOR TO OTHER FISCAL POLICIES

1. Alternative Fiscal Policies: Why the Job Guarantee is Superior

2. (NYTimes) Keep Unemployment From Mushrooming With Preventative Policies

3. If ARRA was designed as a Job Guarantee, it would have created 20million living wage jobs

4. The Job Guarantee is Not Workfare

WHY IT IS NOT ‘JUST’ A PROGRAM FOR FULL EMPLOYMENT

1. Beyond Full Employment: What Argentina’s Plan Jefes Can Teach Us about the Employer of Last Resort {pdf} Summary of the features of JG/ELR, the Argentina program which the government modeled after our ELR proposal, How it behaved as a JG/ELR

2. Poverty, Joblessness and the Job Guarantee

3. Women Want Jobs, Not Handouts (HuffPo)

HOW TO IMPLEMENT IT AND TYPES OF JOBS

1. Completing the Roosevelt Revolution: Why the Time for a Job Guarantee has come {pdf}

2. The Social Enterprise Model for a Job Guarantee in the United States {pdf}

WHY IT IS BETTER THAN BASIC INCOME (selected)

1. “The Job Guarantee: Delivering the Benefits that Basic Income Only Promises”

2. 16 Reasons Matt Yglesias is Wrong about the Job Guarantee vs. Basic Income

3. Guaranteed Income? How about Guaranteed Jobs (10min video)

4. Income for All: Two Visions for a New Economy (video/panel discussion)

(for more on JG vs UBI, see research and media links)

YOUTH PROPOSAL AND UNEMPLOYMENT AS AN EPIDEMIC (SHORT VIDEOS-15min or so)

1. PROPOSAL FOR YOUTH EMPLOYMENT GUARANTEE

2. JG: A CURE TO THE PUBLIC HEALTH AND OTHER SOCIAL PROBLEMS FROM UNEMPLOYMENT: (starts at 24min)

HOW IT FIXES INEQUALITY

1. (NYTimes) Benefits of Economic Expansions Increasingly going tot the Top

2. Reorienting Fiscal Policy: A Bottom Up Approach

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

MORE

1. “Completing the Euro: The Euro Treasury and the Job Guarantee” (with Cruz-Hidalgo and Ehnts) in Revista Economia Critica, 2019 (27): 100-11

oooooo

ooooo

Before: Russia exported cheap energy to European industries & imported European industrial goods

Now: Russia exports cheap energy to Asia & imports Asian industrial goods -Europe is de-industrialising & becoming too reliant on the US, while the economies of China & Russia grow!

oooooo

oooooo

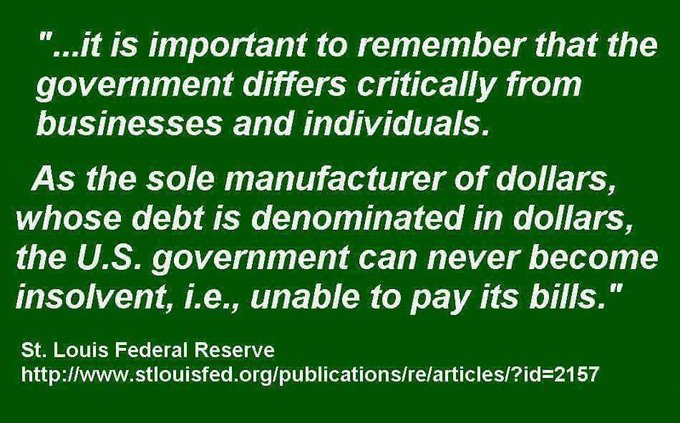

If you are media of any flavor and you still believe that the nation has to “find the money” or that it can go broke, you should be forced to resign. Even alternative media. No excuses for not slamming that shit down hard.

oooooo

Interesting how the MMT reminder that markets can only express relative value, with absolute value a function of prices paid by gov, etc. remains so universally taboo?

docs.google.com

A Framework for the Analysis of the Price Level and Inflation

oooooo

Macro n Cheese Podcast #MMT@CheeseMacro

This week’s @CheeseMacro episode ft.

@les_leopold, Co-founder & Director of The Labor Institute, & Author of, Wall Street’s War on Workers: How Mass Layoffs & Greed Are Destroying the Working Class & What to Do About It, will drop Sat, Jan 6 @ 8 AM EST.

oooooo

Live w/ Warren Mosler – Stock Market – Inflation – CPI – MMT – Q&A https://youtube.com/live/2JDwjOfTp5E?si=UTRNrhUNxzoHzlzm

Bideoa: https://youtu.be/2JDwjOfTp5E

youtube.com

Live w/ Warren Mosler – Stock Market – Inflation – CPI – MMT – Q&A

Special Guest Warren Mosler joins us for a live stream discussion about Inflation, CPI, the economy, stock market and what the future holds for MMT.https://w…

oooooo

GIMMS Presents Warren Mosler, London 1st September 2023 https://youtu.be/f8xHwX3VoMo?si=p-z3PNfXiehoO5Ej

Bideoa: https://youtu.be/f8xHwX3VoMo

youtube.com

GIMMS Presents Warren Mosler, London 1st September 2023

The GIMMS team is delighted to present its event at which Warren Mosler, one of the contributors to the recently launched book Modern Monetary Theory: Key

oooooo

What an expanded BRICS means for Africa’s economy | DW News Africa https://youtu.be/rWmAjZvWmxc?si=9-sT4zAW8wYmlDuB

Bideoa: https://youtu.be/rWmAjZvWmxc

youtube.com

What an expanded BRICS means for Africa’s economy | DW News Africa

The spotlight was on Johannesburg as South Africa hosted the BRICS summit. The leaders of the group of developing nations – Brazil, Russia, India, China and …

oooooo

BRICS Summit 2024 in Russia: a history of strength and strategy shaping … https://youtu.be/rkAG8MrHKbw?si=n0nnlUmNrSbco-Oj

Bideoa: https://youtu.be/rkAG8MrHKbw

youtube.com

BRICS Summit 2024 in Russia: a history of strength and strategy…

The year of Russia’s BRICS presidency under the motto “Strengthening multilateralism for equitable global development and security” has just begun. Let’s loo…