Bill Mitchell-en Towards a progressive concept of efficiency – Part 21

Sarrera gisa, ikus Efizientzia (edo efikazia, 1)2

(i) Laburpena: ekonomia guretzat, guk kontrolatuta eta hiritar guztion ongizaterako3

Ikuspegi aurrerakoia:

a) Aurreko sarreran: mozkin pribatuen aldeko ‘efikazia’4

b) Efikazia eta ortodoxia5

(c) Aurrerakoiak: erdian Gizartea dago jarrita6

(d) Ekonomiaren bi ikuspegi7

(e) Ekonomia eta Gizartea8

(f) Jendea eta ekonomia9

(g) Depresio Handia: Ikasketak langabeziari eta gobernuari buruz10

(h) Finantza Krisi Globala, 2007an: ikasketa berbera11

(i) 1999ko Sharon Beder12

(j) Ikuspegi aurrerakoia eta efikazia13

(k) Langabezia eta Depresio Handian jasotako esperientzia14

(l) Langabezia eta kostu pertsonalak15

(m) Sektore publikoa eta enplegua16

(n) Sektore pribatua17

(ñ) Merkatu librea18

(o) Depresio Handia eta langabezia: Roosevelt-en New Deal19

(p) 2008an, Harry Kelber20

(q) Enplegua sortzeko programak eta efikazia21

(r) Nazionalizazioa eta efikazia22

(s) BPG eta berorren mugak23

(t) BPG-z haratagoko beste adierazle batzuk24

Ondorioak

(1) Tony Benn eta Depresio Handia25:

“…if you can have full employment to kill people, why in God’s name couldn’t you have full employment and good schools, good hospitals, good houses?”

(2) Nahi kolektiboa26

(3) Neoliberalek nahi kolektiboa gorrotatzen dute27

Gehigarria: Job guarantee, lan bermea28

3 Ingelesez: “This is Part 2 of my discussion of how a progressive agenda can escape the straitjacket of neo-liberal thinking and broaden how it presents policy initiatives that have been declared taboo in the current conservative, free market Groupthink. Today, I compare and contrast the neo-liberal vision of efficiency, which is embedded in its view of the relationship between the people, the natural environment and the economy, with what I consider to be a progressive vision, which elevates our focus to Society and sees people embedded organically and necessarily within the living natural environment. It envisions an economy that is created by us, controlled by us and capable of delivering outcomes which advance the well-being of all citizens rather than being a vehicle to advance the prosperity of only a small proportion of citizens.”

4 Ingelesez: “In … – Towards a progressive concept of efficiency – Part 1 – we saw that what mainstream (neo-liberal) economists deem to be ‘best’ or ‘efficient’ is heavily biased towards the fortunes of private profit seekers.

If private firms are producing for markets at the lowest cost and meeting the demands of consumers for those goods and services, then they are maximising profits and being ‘efficient’.

The textbooks all show that under certain conditions (such as, there are no monopoly forces, people are rational and have knowledge of the future and all current alternatives, firms can freely enter and exit the market, ) then free markets are the only efficient way to organise economic activity.

To prosper, the textbooks then suggest we must bend the human settlement and use the natural environment so as to allow these free markets to work in the way prescribed.

We reach perfection when we achieve this state (so that the price of each good sold is exactly equal to the extra resources that were needed to produce it).

The key assumptions made to generate this ‘perfect’ outcome never hold in the real world. Mainstream economists thus deploy the strategy that any move towards this perfect state (for example, cutting minimum wages) will be an improvement and bring the economy closer to efficiency.

They ignore literature (for example, the Theory of Second Best) which shows that if all the assumptions of the mainstream theory do not hold then trying to apply the results of the theory is likely to make things worse not better.”

5 Ingelesez: “Almost all of the statements about ‘efficiency’ in mainstream economic theory are of this type.

Should any of these highly restrictive assumptions not hold (at any point in time), then the models cannot generate any reliable conclusions and any assertions one might make based on these economic theories are groundless – meagre ideological raving.

While the mainstream theory of efficiency does recognise the difference between private costs and benefits (borne and/or enjoyed by firms, individuals) and social costs and benefits (borne and/or enjoyed by all of us as a result of economic transactions between individuals), it rarely focuses on costs that are not quantifiable and private.

And when there are massive social costs arising from failed economic outcomes (for example, mass unemployment), mainstream economists have shown a willingness to define them away in such a way that the outcome remains consistent with their predictions.

So the example I gave yesterday was the claim that unemployment is always voluntary and therefore a product of free, maximising (and efficient) choice between income and leisure. There is a denial that the system can fail to provide enough jobs and thus render any choices that an individual might like to make powerless.”

6 Ingelesez: “For a progressive, the essential goal of getting as much out of the inputs we muster in economic activity remains a goal. That is, this goal is shared with mainstream economists. Otherwise, there is wasteful use of human and natural resources which has no justification.

The questions though are what do we mean when we say we want to get “as much output” as we can and what the inputs that we are acknowledging?

At that point, a progressive vision of efficiency is a world apart from the narrow mainstream neo-liberal concept.

By placing Society rather than private corporations at the centre of our framework, progressives have a broader understanding of costs and benefits, which then conditions how we assess the ‘efficiency’ of an activity.”

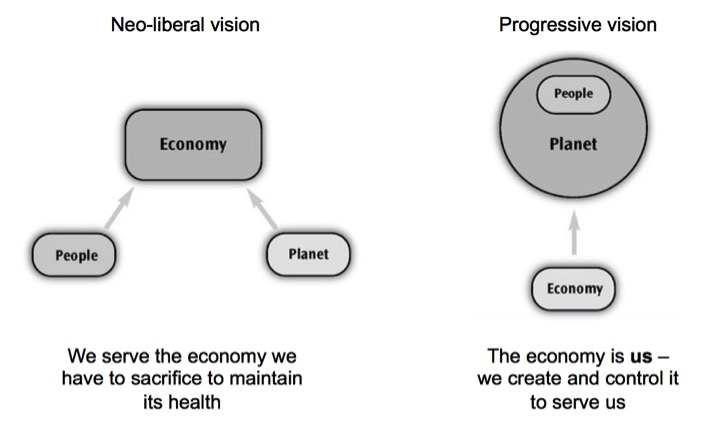

7 Ingelesez: “The right-side panel in the graphic above is what we call a progressive vision of the relationship between the people, the natural environment and the economy.

It leads to a solidaristic or collective approach to problems (sometimes called the All Saints approach), which has has a deep tradition in Western societies.

It recognises that an economic system can impose constraints on individuals which render them powerless. If there are not enough jobs to go around then focusing on the ascriptive characteristics of the unemployed individuals misses the point

Above all, it shifts our attention back onto Society rather than narrowing the focus to the ‘economy’ and corporations. Corporations are just one part of the economy, which is one part of the human settlement.

Once we work within this vision, our notion of efficiency becomes markedly different from that espoused within the neo-liberal vision.”

8 Ingelesez: “Within this construction of reality, the economy is just one part of Society and it is seen as being our construction with people organically embedded and nurtured by the natural environment.

Shenkar-Osorio (2012: Location 1037) says:

This image depicts the notion that we, in close connection with and reliance upon our natural environment, are what really matters. The economy should be working on our behalf. Judgments about whether a suggested policy is positive or not should be considered in light of how that policy will promote our well-being, not how much it will increase the size of the economy.

In this view, the economy is seen as a ‘constructed object’ – that is a product of our own endeavours and policy interventions should be appraised in terms of how functional they are in relation to our broad goals.

Those broad goals are expressed in societal terms rather than in narrow ‘economics’ terms. In the neo-liberal vision, we are schooled to believe that what is good for the corporate, profit-seeking sector is good for us.

Within the progressive vision the goals are articulated in terms of advancing public well-being and maximising the potential for all citizens within the limits of environmental sustainability.

The focus shifts to one of placing our human goals at the centre of our thinking about the economy while at the same time recognising that we are embedded and dependent on the natural environment.”

9 Ingelesez: “In this narrative, people create the economy. There is nothing natural about it.

Concepts such as the ‘natural rate of unemployment’, which suggest that governments should not interfere with the market when there is mass unemployment and leave it to its own equilibrating forces to reach its natural state, are erroneous.

Governments can always choose and sustain a particular unemployment rate. We create government as our agent to do things that we cannot easily do ourselves and we understand that the economy will only serve our common purposes if it is subjected to active oversight and control.

In the progressive vision, collective will is important because it provides the political justification for more equally sharing the costs and benefits of economic activity.

Progressives have historically argued that government has an obligation to create work if the private market fails to create enough employment. Accordingly, collective will means that our government is empowered to use net spending (deficits) to ensure there are enough jobs available for all those who want to work.”

10 Ingelesez: “The contest between the two visions outlined in graphic was really decided during the Great Depression, which taught us that policy intervention was elemental in order to rein in the chaotic and damaging forces of greed and power that underpin the capitalist monetary system.

We learned that so-called ‘market’ signals would not deliver satisfactory levels of employment and that the system could easily come to rest and cause mass unemployment.

We learned that this malaise was brought about by a lack of spending and that the government had the spending capacity to redress these shortfalls and ensure that all those who wanted to work could do so.

From the Great Depression and responses to it we learned that the economy was a construct, not a deity, and that we could control it through fiscal and monetary policy in order to create desirable collective outcomes.

The Great Depression taught us that the economy should be understood as our creation, designed to deliver benefits to us, not an abstract entity that distributes rewards or punishments according to a moral framework.

The government is therefore not a moral arbiter but a functional entity serving our needs. Our experiences during the period of the Great Depression led to a complete rejection of neo-liberal vision.”

11 Ingelesez: “We re-learned the lesson during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). But still the neo-liberal vision dominates. This is in no small part due to the vested interests that bankroll the media, think tanks and academics to indoctrinate the public into accepting the logic of the neo-liberal vision.

The resurgence of the free market paradigm has been accompanied by a well-crafted public campaign where framing and metaphor triumph over operational reality or theoretical superiority.

This process has been assisted by business and other anti-government interests, which have provided significant funds to emergent conservative, free market ‘think tanks’.”

12 Ingelesez: “Sharon Beder wrote in 1999 that these institutions fine tuned “the art of ‘directed conclusions’, tailoring their studies to suit their clients or donors” (Beder, 1999: 30).

Politicians parade these so-called ‘independent’ research findings as the authority needed to justify their deregulation agendas.

Multilateral organisations such as the IMF also continue to distort policy debates with their erroneous claims and, in the case of the IMF, incompetent and error prone modelling.

[Reference: Beder, S. (1999) ‘The Intellectual Sorcery of Think Tanks’, Arena Magazine, 41, June/July, 30–32.]”

13 Ingelesez: “How does the progressive vision expand our understanding of efficiency?

Once society becomes the objective and we recognise that people and the natural environment are the major components of attention, with the economy being a vehicle to advance societal objectives rather than maximising the lot of the profit-seeking, private corporate sector, then our conceptualisation of what is efficient and what is not changes dramatically.

This is especially the case once we understand that our national government is the agent of the people and has the fiscal and legislative capacity (as the currency-issuer) to ensure resources are allocated and used to advance general well-being irrespective of what the corporate or foreign sector might do.

It is clearly ludicrous to conclude that a society is operating efficiently when there are elevated levels of unemployment (people wanting to work who cannot find work) and where large swathes of a nation’s youth are denied access to employment, training or adequate educational opportunities.

It is inconceivable that we would consider a nation is successful if income and wealth inequality was increasing, poverty rates were rising and basic public services were degraded.

In each of these cases, the neo-liberal definition of efficiency could be satisfied, despite the overall well-being of citizens being compromised by the behaviour of the capitalist sector and the policy responses of government.”

14 Ingelesez: “As an example, consider the case for employment guarantees as a solution to mass unemployment.

We know that the job relief programs that the various governments implemented during the Great Depression to attenuate the massive rise in unemployment were very beneficial.

At that time, it was realised that having workers locked out of the production process because there were not enough private jobs being generated was not only irrational in terms of lost income but also caused society additional problems, such as rising crime rates.

Direct job creation was a very effective way of attenuating these costs while the private sector regained its optimism.”

15 Ingelesez: “It is well documented that sustained unemployment imposes significant economic, personal and social costs that include:

-

loss of current output;

-

social exclusion and the loss of freedom;

-

skill loss;

-

psychological harm, including increased suicide rates;

-

ill health and reduced life expectancy;

-

loss of motivation;

-

the undermining of human relations and family life;

-

racial and gender inequality; and

-

loss of social values and responsibility.

Many of these ‘costs’ are difficult to quantify but clearly are substantial given qualitative evidence. Most of these ‘costs’ are ignored by the neo-liberal concept of efficiency, in part, because they accumulate outside the ‘market’ and are not quantifiable in the narrow terms of the exchange between buyers and sellers.

Most people do not consider the irretrievable nature of these losses. Every day that unemployment remains above the full employment level the economy is foregoing billions in lost output and national income that is never recovered and the unemployed individuals and their families endure the other related costs.

The magnitude of these losses and the fact that most commentators and policy makers prefer unemployment to direct job creation, shows the powerful hold that neo-liberal thinking has had on policy makers. How is it rational to tolerate these massive losses which span generations?”

16 Ingelesez: “When direct public sector job creation is mooted as a solution, the neo-liberals chime in with their relentless claims about waste and inefficiency.

They use terms such as ‘boondoggling’ and ‘leaf-raking’ to condition our responses that these schemes just make useless work for the sake of it.

The terms ‘boondoggling’, ‘make-work’ and ‘leaf-raking’ are all synonomous and are meant to imply that nothing good comes from this type of program.

Please read my blogs – Boondoggling and leaf-raking … and The ultimate boondoggle courtesy of slack government policy – for more discussion on this point.”

17 Ingelesez: “The same conservatives laud the virtues of the private sector as they create hundreds of thousands of low-skill, low-paid, precarious and mind-numbing jobs but hate, with an irrational passion, the idea that the public sector could employ workers that the private sector doesn’t want and get them to work on community development projects at some socially-inclusive wage.”

18 Ingelesez: “While these free market zealots only see the massive waste of public sector job programs (because ‘the market’ didn’t create the jobs) they fail to see that:

1. National income is being produced which multiplies into more income via increased spending throughout the economy.

2. The massive loss of national income from mass unemployment are attenuated.

3. The huge intergenerational damage that entrenched unemployment to individuals, their families and the broader society is reduced.”

19 Ingelesez: “These attacks on public sector job creation reached hysterical proportions during the Great Depression in the US, when President Roosevelt introduced his New Deal program, which included the Public Works Administration (PWA) initiative.

The facts are clear. The Public Works Administration (PWA) created hundreds of thousands of jobs and the work helped restore ageing public infrastructure (such as, roads, dams and bridges). Many new buildings were constructed during this period (schools, recreational spaces, libraries, hospitals) and have delivered benefits to the generations that followed.

There are huge reminders of the legacy of this era of public intervention by way of direct job creation. The Tennessee Valley Authority was a huge hydro-electricity project which brought electricity and prosperity to some of the poorest rural areas of the US.”

20 Ingelesez: “As Harry Kelber wrote in 2008, at the time, the private electricity providers stridently opposed the challenge to their monopoly control. The upshot was that the project forced them to reduce their power charges.

In general, the dynamism of the public sector at that time caused huge outcries from the capitalists who didn’t want challenges to their cosy profit making industries from public sector enterprise.

The capitalists lost out to society! It is a repeating lesson that progressives seem to have forgot.

There are many examples of how job creation programs around the World have left a positive legacy while attenuating the immediate damage of mass unemployment.

[Reference: Kelber, H. (2008) ‘How the New Deal Created Millions of Jobs

To Lift the American People from Depression ‘, The Labor Educator, May 9, 2008. LINK.]”

21 Ingelesez: “Thus, when evaluating whether job creation programs are ‘efficient’ we have to consider the benefits for the workers and their families of having a job both in income terms and in the broader socio-psychological terms.

We have to consider the reduction in the intergenerational costs of children growing up in households where the parents work. We know from research that the disadvantage of unemployed parents is passed onto to their children, which means the costs of the lack of jobs extends well beyond the immediate period.

We have to consider the benefits of social stability where all citizens have access to work and income security. And many more factors that are ignored by the neo-liberal vision and its concept of efficiency.”

22 Ingelesez: “The same sort of evaluation would be relevant when assessing whether re-nationalisation was a worthwhile strategy for a progressive government to take.

The old hoary that the conservatives raise that these industries were havens of ‘inefficiency’ always ignore the benefits of workers having secure employment and their families enjoying stable incomes. They always ignore the other pathologies that accompany mass unemployment.

And as we will see when I write the second part on the benefits of nationalisation, these conservative attacks on re-nationaisation also ignore a range of progressive benefits of having key sectors like energy, banking and transport in public ownership.

For example, it is much easier for a government to deal with climate change if it owns the energy companies. Technology shifts are much more efficient in this context. ...”

Laster arituko gara nazionalizazioaz.

23 Ingelesez: “We noted … that the mainstream vision measures success in terms of GDP. Higher growth is deemed good and vice versa.

However, GDP is a flawed measure of societal or community well being and it largely ignores issues relating to environmental sustainability.

Instead of measuring success, for example, using GDP, progressives will seek to use other measures which capture essential characteristics of Society that are define its health.”

24 Ingelesez: “Such measures as the Index of Social Health (ISH) (which includes indicators of child poverty, child abuse, infant mortality, unemployment, wages, health insurance coverage, teen suicide rates, teen drug abuse, high school dropouts, old age poverty, crime rates, food insecurity, housing, and income inequality) provide a broader index of social well-being.

Other measures such as the Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI) also provides a broader measure of the state of the nation and the role the economy is playing in advancing social and environmental well-being.

The GPI, in particular, attempts to estimate the long-term environmental damage that our economic settlement creates.

A similar approach is taken by the Gross Sustainable Development Product (GSDP) measure.

The United Nations Human Development Index (UNHDI) “was created to emphasize that people and their capabilities should be the ultimate criteria for assessing the development of a country, not economic growth alone.”

Once again, the focus of our attention is on Society, community and environment. The economy serves us not the other way around.”

25 Ingelesez: “In an interview with the American radio service – PBS – on October 17, 2000, British Labour politician Tony Benn was asked whether the Great Depression led to a “huge loss of faith in markets and governments”, to which he replied:

Well, before the Great Depression, the gamblers ran capitalism and brought the economies down. And what happened? The war followed the Great Depression. In war you mobilize everything. Governments tore down the railings in Britain and America to make bullets. They rationed food, they conscripted people, and they sent them to die. The state took over. And after the war people said, “If you can plan for war, why can’t you plan for peace?” When I was 17, I had a letter from the government saying, “Dear Mr. Benn, will you turn up when you’re 17 1/2? We’ll give you free food, free clothes, free training, free accommodation, and two shillings, ten pence a day to just kill Germans.” People said, well, if you can have full employment to kill people, why in God’s name couldn’t you have full employment and good schools, good hospitals, good houses? And the answer was that you can’t do it if you allow profit to take precedent over people. And that was the basis of the New Deal in America and of the postwar Labor government in Great Britain and so on.

This is clearly is a compelling basis for a progressive narrative which does not see the economy as a separable, natural entity from the people and the natural environment.”

26 Ingelesez: “Collective will is important because it provides the political justification for sharing the costs and benefits of economic activity more generally.”

27 Ingelesez: “The neo-liberals hate collective will because they desire the powers of the state to be exercised to their own advantage.”

28 Ingelesez: “There is a further dimension to efficiency that progressives need to come to terms with. I deal with it in this blog – If you can have full employment killing Germans ….”:

So if we can have full employment by killing Germans, then as long as we value alternative activities such as first-class health care, education, recreational services, environmental care services etc then we can certainly “productively” engage any idle labour that the capital system creates by offering a Job Guarantee.

The introduction of a Job Guarantee is not the panacea for all ills. But it should be an essential part of any progressive policy intervention.”